Great Fire of 1901

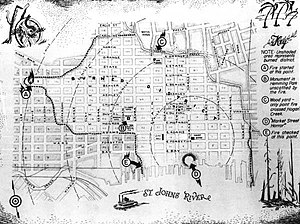

Map of the Great Fire of 1901 that destroyed Downtown Jacksonville | |

| Date | May 3, 1901 |

|---|---|

| Location | Jacksonville, Florida |

| Outcome | 2,367 structures destroyed 7 killed |

The Great Fire of 1901 was a conflagration that occurred in Jacksonville, Florida, on May 3, 1901. It was one of the worst disasters in Florida history and the third largest urban fire in the U.S., next to the Great Chicago Fire, and the 1906 San Francisco fire.[1]

Fire

[edit]Origin

[edit]In 1901, Jacksonville was a city which consisted mainly of wooden buildings with wood shingled roofs. The city itself had been suffering under a prolonged drought,[2] leaving the building exteriors across the city dry and fire-prone. At around noon on Friday, May 3, 1901, workers at the Cleaveland Fibre Factory, located on the corner of Beaver and Davis Streets, left for lunch. Several minutes later, sparks from the chimney of a nearby building started a fire in a pile of Spanish moss that had been laid out to dry. First, factory workers tried to put it out with a few buckets of water, as they had frequently done on similar occasions.[3] However, the blaze was soon out of control due to the wind picking up out of the east.[4] A brisk northwest wind fanned the flames, which "spread from house to house, seemingly with the rapidity that a man could walk".[2]

In eight hours, the fire burned 146 city blocks, destroyed more than 2,367 buildings, and left almost 10,000 residents homeless, including the Afro-American Insurance Association, the first insurance company in the state.[5] It is said the glow from the flames could be seen in Savannah, Georgia, and the smoke plumes in Raleigh, North Carolina.[6]

James Weldon Johnson, principal of a local school claimed, however, that firemen tried to save the fire from spreading to a white neighborhood, allowing black parts of town to burn down in the process:

"We met many people fleeing. From them we gathered excitedly related snatches: the fiber factory catches afire - the fire department comes - fanned by a light breeze, the fire is traveling directly east and spreading out to the north, over the district where the bulk of Negroes in the western end of the city live - the firemen spend all their efforts saving a low row of frame houses just across the street on the south side of the factory, belonging to a white man named Steve Melton."[7]

Aftermath

[edit]Florida Governor William S. Jennings declared martial law in Jacksonville and dispatched several state militia units to help. Reconstruction began immediately, and the city was returned to civil authority on May 17. Seven human deaths were reported.[8] St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, built of bricks in 1887, was the only major church in the city to withstand the fire. The Duval County Courthouse and all its real estate records were destroyed in the fire. To this day real estate deeds in Duval County refer either to "the current public records of Duval County, Florida" or, if the records predate the fire, "the former public records of Duval County, Florida." It is the only county in Florida for which that is the case.[citation needed] The only existing pre-Fire real estate records are title abstracts saved by Title and Trust, a title company that still charges for their use.[citation needed]

Reconstruction

[edit]New York City architect Henry John Klutho helped rebuild the city. He and other architects, enamored by the "Prairie Style" of architecture then being popularized by architect Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago and other Midwestern cities, designed exuberant local buildings with a Florida flair. Buildings designed by Klutho were Dyal-Upchurch Building (1902), Carnegie Library (1905), Bisbee Building (1909), Morocco Temple (1910), and the Florida Baptist Building (1924). While many of Klutho's buildings were demolished or abandoned by the 1980s, several of his creations remain, including his most prominent work, the St. James Building. The Jacksonville City Hall currently uses the St. James Building.[9][10] Local charity Fresh Ministries recently[when?] restored the Klutho Apartments, in Springfield, and converted them into office space for the Community Development Corporation's Operation New Hope.[citation needed] Jacksonville has one of the largest collections of Prairie Style buildings (particularly residences) outside the Midwest.[11]

See also

[edit]- Hotel Roosevelt fire: costly 1963 fire in downtown Jacksonville

- History of Jacksonville, Florida

- List of historic fires

Notes

[edit]- ^ Davis, Ennis (October 20, 2009). "The Great Jacksonville Fire of 1901". Metro Jacksonville. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Kerr, Jessie-Lynne (May 2, 1999). "Like the Phoenix, Jacksonville Rose from the Ashes after the Great Fire". The Florida Times Union. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Fire!". The Great Fire of Jacksonville: An Artistic Description of a Gloomy Affair. University of Florida Library. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Foley, Bill; Wood, Wayne W. (2001). The Great Fire of 1901. Published by The Jacksonville Historical Society, Jacksonville, FL

- ^ "Remembering Abraham Lincoln Lewis: Philanthropist, human rights pioneer and entrepreneur who got his start in Madison". November 25, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Davis, T. Frederick (1925). History of Jacksonville Florida and Vicinity 1513 to 1924. Florida Heritage Collection: The Florida Historical Society. p. 227.

- ^ Davis, Ennis (February 10, 2014). "10 Facts About Jacksonville's Black History". Metro Jacksonville. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Great Jacksonville Fire of 1901". Florida Memory. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Penland, Dolly (March 30, 2007). "Dyal-Upchurch – then and now". Jacksonville Business Journal. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ Wood, Wayne. "Jacksonville's Architectural Heritage, Dyal-Upchurch Building". Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ Davis, Ennis (August 4, 2010). "A Jacksonville Landmark: Prairie School Architecture". Metro Jacksonville. Retrieved May 6, 2016.