The Great Escape (film)

| The Great Escape | |

|---|---|

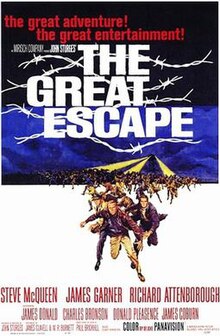

Theatrical release poster by Frank McCarthy | |

| Directed by | John Sturges |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill |

| Produced by | John Sturges |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Daniel L. Fapp |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 172 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $3.8 million[1] |

| Box office | $11.7 million |

The Great Escape is a 1963 American epic historical war adventure film[2] starring Steve McQueen, James Garner and Richard Attenborough and featuring James Donald, Charles Bronson, Donald Pleasence, James Coburn, Hannes Messemer, David McCallum, Gordon Jackson, John Leyton and Angus Lennie. It was filmed in Panavision, and its musical score was composed by Elmer Bernstein.

Based on Paul Brickhill's 1950 non-fiction book of the same name, the film depicts a heavily fictionalized version of the mass escape by British Commonwealth prisoners of war from German POW camp Stalag Luft III during the Second World War. The film made numerous compromises for its commercial appeal, including its portrayal of American prisoners' involvement in the escape.

The Great Escape was made by The Mirisch Company, released by United Artists, and produced and directed by John Sturges. The film had its Royal World Premiere at the Odeon Leicester Square in London's West End on 20 June 1963.[3] The Great Escape received critical acclaim and emerged as one of the highest-grossing films of the year, winning McQueen the award for Best Actor at the Moscow International Film Festival,[4] and is considered a classic.[5] The film is also noted for its motorcycle chase and jump scene, which is considered one of the best stunts ever performed.[6][7][8]

Plot

[edit]In 1943, a group of Allied POWs who have repeatedly escaped from camps across the Third Reich are moved to a new camp under the command of Luftwaffe Colonel von Luger. He warns British Group Captain Ramsey—the highest-ranked POW officer and their de facto leader—that any man who escapes will be shot. Privately von Luger opposes such measures, but the Gestapo, tired of the disruption caused by breakouts elsewhere, has threatened to intervene if the Luftwaffe cannot stop them for good.

Several prisoners ignore the threat and attempt to escape on the first day, but none succeed. Hilts, a notoriously prolific escapee, notices a blind spot at the fence and purposefully gets caught before the guards can realize his discovery. Sentenced to "the cooler”,[9] he is placed in a cell next to Ives, and the two become friends.

RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett re-establishes "the X Organisation", the escape-planning committee at their former camp, with Ramsey's tacit approval. He argues that they can help the Allied war effort by breaking out an unprecedented 250 men simultaneously, forcing the Germans to divert significant manpower away from the front.

The POWs begin working on three tunnels: "Tom", "Dick", and "Harry". Hendley secures vital objects on the black market and forms a bond with expert forger Blythe. Sedgwick makes picks and air bellows, Welinski and Dickes oversee the digging, MacDonald gathers intelligence, Griffith sews civilian disguises, and Ashley-Pitt devises a method of hiding the excavated dirt. Digging and manufacturing noise is masked by a choir, led by Cavendish, who also surveys the tunnels' routes. Aware that Hilts is planning to jump the fence, Bartlett asks him to scout out the surrounding area and then allow himself to be recaptured so he can draw maps for the X Organisation. Hilts refuses out of pride.

When "Tom" nears completion first, Bartlett orders "Dick" and "Harry" sealed off. Hilts, Hendley, and Goff brew potato moonshine with a homemade still and celebrate the Fourth of July with the camp, but the guards accidentally find "Tom" mid-party. A despondent Ives snaps, frantically climbs the fence, and is shot dead. Hilts, shaken, agrees to Bartlett's proposal.

Bartlett orders "Harry" reopened. When the tunnel partially collapses, Welinski breaks down and confides to Dickes that he is claustrophobic. He tries to climb the fence like Ives, but Dickes manages to calm him down and prevent him being shot. Blythe finds he is going blind due to progressive myopia, and Hendley takes it upon himself to be his eyes during the escape.

The prisoners complete "Harry", but on the night of the escape they break to the surface and find themselves 20 feet short of the forest, and still within sight of the guards. Guided by Hilts tugging on a rope as a signal—and aided by a fortuitous air raid blackout—dozens of men flee before Cavendish slips and makes a noise. An impatient Griffith surfaces while a guard investigates and is captured, ending the breakout.

The 76 escapees flee throughout Europe and three manage to escape. Welinski and Dickes row to a port and board a ship for Sweden, while Sedgwick cycles to France, where the Resistance smuggles him to Spain.

The rest are unsuccessful: Cavendish hitches a ride on a truck, but is turned in by the driver. Hilts steals a motorcycle and heads for the German-Swiss border, chased by soldiers, but after jumping one line of tank barriers his bike is shot and he is recaptured. Hendley and Blythe steal a Luftwaffe training plane to fly to Switzerland, but crash when the engine fails; Blythe is shot and Hendley recaptured. At a railway station, Kuhn, a Gestapo guard from the camp, helps search among the disembarking passengers for escapees; Ashley-Pitt kills him to prevent him recognizing Bartlett, and is then also shot dead. However, Bartlett and MacDonald are still caught when another Gestapo officer tricks MacDonald into speaking English while boarding a bus.

Fifty of the men—including Bartlett, MacDonald and Cavendish—are loaded into trucks, taken to a field, and shot dead on Hitler's direct orders. Seventeen of the men (including Hilts and Hendley) are sent back, and the rest are sent to death camps.

When Hendley hears the news on his return to the camp with the survivors, asks Ramsey if the escape was worth it. Von Luger, ashamed by the murders, is relieved of command by the Gestapo and driven away to an uncertain fate, but as he leaves he tells a returning Hilts that it looks like the American will be the one who gets to see Berlin first. Hilts is sent to the cooler, where he begins planning his next escape.

Cast

[edit]- Steve McQueen as Captain Virgil Hilts ('The Cooler King'): one of three Americans in the camp, a particularly persistent escapee with an irreverent attitude.

- James Garner as Flight Lieutenant Bob Hendley ('The Scrounger'): American RAF officer, responsible for finding materials on the black market for the escape attempt; forms a close friendship with Blythe.

- Richard Attenborough as Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett ('Big X'): RAF officer and ringleader of the escape committee.

- James Donald as Group Captain Ramsey ('The SBO'): most senior British & Allied officer in the camp, serves as an intermediary between the Germans and the POWs as their de facto leader.

- Charles Bronson as Flight Lieutenant Danny Welinski ('Tunnel King'): Polish RAF officer; despite having dug 17 escape tunnels in other camps, is severely claustrophobic.

- Donald Pleasence as Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe ('The Forger'): mild-mannered English forger; forms close friendship with Hendley.

- James Coburn as Flying Officer Sedgwick ('The Manufacturer'): an Australian officer who constructs tools for the escape.[note 1]

- Hannes Messemer as Oberst von Luger ('The Kommandant'): Commandant of the camp and a senior Luftwaffe officer.

- David McCallum as Lieutenant-Commander Eric Ashley-Pitt ('Dispersal'): a Fleet Air Arm officer; devises a way to get rid of the tunnel dirt.

- Gordon Jackson as Flight Lieutenant Andy MacDonald ('Intelligence'): Bartlett's second-in-command.

- John Leyton as Flight Lieutenant Willie Dickes ('Tunnel King'): Welinski's best friend and co-lead on tunnel design and construction.

- Angus Lennie as Flying Officer Archie Ives ('The Mole'): anxious Scottish airman who befriends Hilts in the cooler.

- Nigel Stock as Flight Lieutenant Dennis Cavendish ('The Surveyor'): surveys the tunnel routes.

- Robert Graf as Werner ('The Ferret'): young, naive guard whom Hendley befriends and exploits for black market contraband.

- Jud Taylor as Second Lieutenant Goff: the camp's third American.

- Hans Reiser as Kuhn: Gestapo officer and ardent Nazi.

- Harry Riebauer as Stabsfeldwebel Strachwitz: the senior NCO amongst the German guards.

- William Russell as Flight Lieutenant Sorren ('Security'): British officer.

- Robert Freitag as Hauptmann Posen: von Luger's adjutant.

- Ulrich Beiger as Preissen: Gestapo officer.

- George Mikell as SD Hauptsturmführer Dietrich: SS officer.

- Lawrence Montaigne as Flying Officer Haynes ('Diversions'): Canadian officer.

- Robert Desmond as Pilot Officer Griffith ('Tailor'): British officer; provides civilian clothes and military uniforms to disguise the escapees.

- Til Kiwe as Frick

- Heinz Weiss as Kramer

- Tom Adams as Flight Lieutenant Dai Nimmo ('Diversions'): Welsh officer.

- Karl-Otto Alberty as SD Untersturmführer Steinach: SS officer.

- Arthur Atkinson as British Officer Charlie (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Writing

[edit]In 1963, the Mirisch brothers worked with United Artists to adapt Paul Brickhill's 1950 book The Great Escape. Brickhill had been a very minor member of the X Organisation at Stalag Luft III, who acted as one of the "stooges" who monitored German movements in the camp. The story had been adapted as a live TV production, screened by NBC as an episode of The Philco Television Playhouse on January 27, 1951.[10] The live broadcast was praised for engineering an ingenious set design for the live broadcast, including creating the illusion of tunnels.[11] The film's screenplay was adapted by James Clavell, W. R. Burnett and Walter Newman.

Casting

[edit]

Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn all had recently worked with director John Sturges on his 1960 motion picture, The Magnificent Seven.

Steve McQueen has been credited with the most significant performance. Critic Leonard Maltin wrote that "the large, international cast is superb, but the standout is McQueen; it's easy to see why this cemented his status as a superstar".[12] This film established his box-office clout. Hilts was based on at least three pilots, David M. Jones, John Dortch Lewis[13] and Bill Ash.[14][15][16]

Richard Attenborough's Sqn Ldr Roger Bartlett RAF, "Big X", was based on Roger Bushell, the South African-born British POW who was the mastermind of the real Great Escape.[17] This was the film that first brought Attenborough to common notice in the United States. During World War II, Attenborough served in the Royal Air Force. He volunteered to fly with the Film Unit, and after further training (where he sustained permanent ear damage), he qualified as a sergeant. He flew on several missions over Europe, filming from the rear gunner's position to record the outcome of Bomber Command sorties. (Richard Harris was originally announced for the role.)[18]

Group Captain Ramsey RAF, "the SBO" (Senior British Officer), was based on Group Captain Herbert Massey, a World War I veteran who had volunteered in World War II. Massey walked with a limp, and in the movie Ramsey walks with a cane. Massey had suffered severe wounds to the same leg in both wars. There would be no escape for him, but as SBO he had to know what was going on. Group Captain Massey was a veteran escaper himself and had been in trouble with the Gestapo. His experience allowed him to offer sound advice to the X-Organisation.[19] Another officer who is likely to have inspired the character of Ramsey was Wing Commander Harry Day.

Flt Lt Colin Blythe RAF, "The Forger", was based on Tim Walenn and played by Donald Pleasence.[20] Pleasence had served in the Royal Air Force during World War II. He was shot down and spent a year in German prisoner-of-war camp Stalag Luft I. Charles Bronson had been a gunner in the USAAF and had been wounded, but never shot down. Like his character, Danny Welinski, he suffered from claustrophobia because of his childhood work in a mine. James Garner had been a soldier in the Korean War and was twice wounded. He was a scrounger during that time, as is his character.[21]

Hannes Messemer's Commandant, "Colonel von Luger", was based on Oberst Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau.[22] Messemer had been a POW in Russia during World War II and had escaped by walking hundreds of miles to the German border.[23] He was wounded by Russian fire, but was not captured by the Russians. He surrendered to British forces and then spent two years in a POW facility in London known as the London Cage.

Angus Lennie's Flying Officer Archibald Ives, "The Mole", was based on Jimmy Kiddel, who was shot dead while trying to scale the fence.[24]

The film is accurate in showing that only three escapees made home runs, although the people who made them differed from those in the film. The escape of Danny and Willie in the film is based on two Norwegians who escaped to Sweden, Per Bergsland and Jens Müller, while the escape of Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Flying Officer Sedgwick, "the Manufacturer", to Spain, was based on Dutchman Bram van der Stok. James Coburn, an American, was cast in the role of Sedgwick who was an amalgamation of Flt Lt Albert Hake, an Australian serving in the RAF, the camp's compass maker, and Johnny Travis, the real manufacturer.

Tilman 'Til Kiwe' Kiver played the German guard "Frick", who discovers the escape. Kiwe had been a German paratrooper officer who was captured and held prisoner at a POW camp in Colorado. He made several escape attempts, dyeing his uniform and carrying forged papers. He was captured in the St. Louis train station during one escape attempt. He won the Knight's Cross before his capture and was the cast member who had actually performed many of the exploits shown in the film.

Filming

[edit]The film was made on location in Germany at the Bavaria Film Studio in the Munich suburb of Geiselgasteig in rural Bavaria, where sets for the barrack interiors and tunnels were constructed. The camp was built in a clearing of the Perlacher Forst (Perlacher Forest) near the studio.[25][26] The German town near the real camp was Sagan (now Żagań, Poland); it was renamed Neustadt in the film.[26] Many scenes were filmed in and around the town of Füssen in Bavaria, including its railway station. The nearby district of Pfronten,[27] with its distinctive St. Nikolaus Church and scenic background, also appears often in the film.[26] The first scenes involving the railway were filmed on the Munich–Holzkirchen line at Großhesselohe station ("Neustadt" station in the movie) and near Deisenhofen. Hendley and Blythe's escape from the train was shot on the Munich–Mühldorf railway east of Markt Schwaben. The station where Bartlett, MacDonald and Ashley-Pitt arrive is Füssen station, whereas the scene of Sedgwick (whose theft of a bike was shot in Markt Schwaben) boarding a train was created in Pfronten-Ried station on the Ausserfern Railway.[28][29] The castle Hendley and Blythe fly by while attempting to escape is Neuschwanstein Castle.[30]

The motorcycle chase scenes with the barbed wire fences were shot on meadows outside Füssen, and the "barbed wire" that Hilts crashes into before being recaptured was simulated by strips of rubber tied around barbless wire, constructed by the cast and crew in their spare time.[31] Insurance concerns prevented McQueen from performing the film's notable motorcycle leap, which was done by his friend and fellow cycle enthusiast Bud Ekins, who resembled McQueen from a distance.[32] When Johnny Carson later tried to congratulate McQueen for the jump during a broadcast of The Tonight Show, McQueen said, "It wasn't me. That was Bud Ekins." However, McQueen and Australian Motocross champion Tim Gibbes both performed the stunt on camera for fun, and according to second unit director Robert Relyea, the stunt in the final cut of the movie could have been performed by any of the three men.[33] Other parts of the chase were done by McQueen, playing both Hilts and the soldiers chasing him, because of his skill on a motorcycle.[34] The motorcycle was a Triumph TR6 Trophy which was painted to look like a German machine. The restored machine is currently on display at Triumph's factory at Hinckley, England.[35] Filming started on June 4, 1962 and ended in October 1962.

Historical accuracy

[edit]

The film accurately represented many details of the escape, including the layout of the camp, the different escape plans employed, and the fact that only three of the 76 escapees successfully reached their destinations. The names of the characters are fictitious, but are based on real men, in most cases being composites of several people. However, a number of changes were made to increase the film's drama and appeal to an American audience, with some scenes being heavily or completely fictionalised. The screenwriters also significantly increased the involvement of American POWs in the escape. A few American officers in the camp initially helped dig the tunnels and worked on the early plans, but they were moved away seven months before the escape, which ended their involvement.[36][37] The real escape was by largely British and other Allied personnel, with the exception of American Johnnie Dodge, who was a British officer.[30] The film omits the crucial role that Canadians played in building the tunnels and in the escape itself. Of the 1,800 or so POWs, 600 were involved in preparations: 150 of those were Canadian. Wally Floody, an RCAF pilot and former miner who was the real-life "tunnel king", was engaged as a technical advisor for the film.[38]

Ramsey tells Von Luger that it is the sworn duty of every officer to attempt escape. In reality, there was no requirement in the King's Regulations, or in any form of international convention.[39]

The film shows the tunnel code-named Tom with its entrance under a stove and Harry's in a drain sump in a washroom. In reality, Dick's entrance was the drain sump, Harry's was under the stove, and Tom's was in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney.[40]

Former POWs asked the filmmakers to exclude details about the help they received from their home countries, such as maps, papers, and tools hidden in gift packages, lest it jeopardise future POW escapes. The filmmakers complied.[41]

The film omits any mention that many Germans willingly helped in the escape itself. The film suggests that the forgers were able to make near-exact replicas of just about any pass that was used in Nazi Germany. In reality, the forgers received a great deal of assistance from Germans who lived many hundreds of miles away on the other side of the country. Several German guards, who were openly anti-Nazi, also willingly gave the prisoners items and assistance of any kind to aid their escape.[39] The need for such accuracy produced much eyestrain, but unlike in the film, there were no cases of blindness. Some, such as Frank Knight, gave up forging because of the strain, but he certainly did not suffer the same ocular fate as the character of Colin Blythe in the film.[39] In fact, no one in the film says that Colin Blythe's blindness is the result of eyestrain. He identifies his problem as "progressive myopia", suggesting that he has not only heard of the condition but has also been diagnosed.

The film depicts the escape taking place in ideal weather conditions, whereas at the time much was done in freezing temperatures, and snow lay thick on the ground.[39] In reality there were no escapes by aircraft or motorcycle: McQueen requested the motorcycle sequence, which shows off his skills as a keen motorcyclist. He did the stunt riding himself (except for the final jump, done by Bud Ekins).[42]

In the film, Hilts incapacitates a German soldier for his motorcycle, Ashley-Pitt kills Kuhn, a Gestapo officer, when he recognizes Bartlett waiting to pass through a Gestapo checkpoint at a railway station and Hendley knocks out a German guard at the airfield. Sedgwick witnesses the killing of German officers at a French Cafe by the French resistance. No German personnel were killed or injured by the real escapees.

In the film Blythe is shown being killed by German Border guards after the training aircraft that Hendley stole crashes just short of the border; this incident never happened. Three truckloads of recaptured POWs drive in three directions. One truck contains 20 prisoners who are invited to stretch their legs in a field, whereupon they are all machine gunned in a single massacre, with the implication that the other two were killed in the same manner; in reality, the POWs were shot individually or in pairs. The majority of the POWs were killed by pistol shots taken by Gestapo officers; however, at least ten of them were killed in a manner like that portrayed in the film: Dutchy Swain, Chaz Hall, Brian Evans, Wally Valenta, George McGill, Pat Langford, Edgar Humphreys, Adam Kolanowski, Bob Stewart and Henry "Hank" Birkland.[43][44][45][46][47][48][39] The film depicts the three prisoners who escape to freedom as British, Polish, and Australian; in reality, they were Norwegian (Jens Müller and Per Bergsland) and Dutch (Bram van der Stok).[49]

In 2009, seven POWs returned to Stalag Luft III for the 65th anniversary of the escape[50] and watched the film. According to the veterans, many details of the first half depicting life in the camp were authentic, e.g. the death of Ives, who tries to scale the fence, and the actual digging of the tunnels. The film has kept the memory of the 50 executed airmen alive for decades and has made their story known worldwide, if in a distorted form.[30] British author Guy Walters notes that a pivotal scene in the film where MacDonald blunders by replying in English to a suspicious Gestapo officer saying, "Good luck", is now so strongly imprinted that historians have accepted it as a real event, and that it was Bushell's partner Bernard Scheidhauer who made the error. However, Walters points out that an historical account says that one of the two men said "yes" in English in response to a Kripo man's questions without any mention of "good luck" and notes that as Scheidhauser was French, and Bushell's first language was English, it seems likely that if a slip did take place, it was made by Bushell himself, and says the "good luck" scene should be regarded as fiction.[39]

Music

[edit]The film's iconic music was composed by Elmer Bernstein, who gave each major character his own musical motif based on the Great Escape's main theme.[51] Its enduring popularity helped Bernstein live off the score's royalties for the rest of his life.[52] Critics have said the film score succeeds because it uses rousing militaristic motifs with interludes of warmer softer themes that humanizes the prisoners and endears them to audiences; the music also captures the bravery and defiance of the POWs.[53] The main title's patriotic march has since become popular in Britain, particularly with fans of the England national football team.[54] However, in 2016, the sons of Elmer Bernstein openly criticized the use of the Great Escape theme by the Vote Leave campaign in the UK Brexit referendum, saying "Our father would never have allowed UKIP to use his music" because he would have strongly opposed the party.[55]

- Intrada Records (release)

In 2011 Intrada, a company specializing in film soundtracks, released a digitized re-mastered version of the full film score based on the original 1/4" two-track stereo sessions and original 1/2" three-channel stereo masters.[56]

Disc one

[edit]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Main Title" | 2:30 |

| 2. | "At First Glance" | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Premature Plans" | 2:28 |

| 4. | "If At Once" | 2:31 |

| 5. | "Forked" | 1:28 |

| 6. | "Cooler" | 1:59 |

| 7. | "Mole" | 1:28 |

| 8. | ""X"/Tonight We Dig" | 1:30 |

| 9. | "The Scrounger/Blythe" | 3:50 |

| 10. | "Water Faucet" | 1:23 |

| 11. | "Interruptus" | 1:33 |

| 12. | "The Plan/The Sad Ives" | 1:43 |

| 13. | "Green Thumbs" | 2:28 |

| 14. | "Hilts And Ives" | 0:38 |

| 15. | "Cave In" | 2:01 |

| 16. | "Restless Men" | 1:56 |

| 17. | "Booze" | 1:47 |

| 18. | ""Yankee Doodle"" | 0:55 |

| 19. | "Discovery" | 3:40 |

| Total length: | 57:35 | |

Disc two

[edit]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Various Troubles" | 3:52 |

| 2. | "Panic" | 2:05 |

| 3. | "Pin Trick" | 0:59 |

| 4. | "Hendley's Risk" | 1:43 |

| 5. | "Released Again/Escape Time" | 5:25 |

| 6. | "20 Feet Short" | 3:06 |

| 7. | "Foul Up" | 2:37 |

| 8. | "At The Station" | 1:33 |

| 9. | "On The Road" | 3:27 |

| 10. | "The Chase/First Casualty" | 6:49 |

| 11. | "Flight Plan" | 2:09 |

| 12. | "More Action/Hilts Captured" | 6:07 |

| 13. | "Road's End" | 2:06 |

| 14. | "Betrayal" | 2:20 |

| 15. | "Three Gone/Home Again" | 3:13 |

| 16. | "Finale/The Cast" | 2:47 |

| Total length: | 1:18:58 | |

Disc three

[edit]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Main Title" | 2:07 |

| 2. | "Premature Plans" | 2:08 |

| 3. | "Cooler And Mole" | 2:26 |

| 4. | "Blythe" | 2:13 |

| 5. | "Discovery" | 2:54 |

| 6. | "Various Troubles" | 2:40 |

| 7. | "On The Road" | 2:54 |

| 8. | "Betrayal" | 2:05 |

| 9. | "Hendley's Risk" | 2:24 |

| 10. | "Road's End" | 2:00 |

| 11. | "More Action" | 1:57 |

| 12. | "The Chase" | 2:49 |

| 13. | "Finale" | 3:14 |

| Total length: | 49:11 | |

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Great Escape grossed $11.7 million at the box office,[57] after a budget of $4 million.[58] It became one of the highest-grossing films of 1963, despite heavy competition. In the years since its release, its audience has broadened, cementing its status as a cinema classic.[5] It was entered into the 3rd Moscow International Film Festival, where McQueen won the Silver Prize for Best Actor.[59]

Critical response

[edit]Contemporary reviews for the film were mostly positive. In 1963, The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote: "But for much longer than is artful or essential, The Great Escape grinds out its tormenting story without a peek beneath the surface of any man, without a real sense of human involvement. It's a strictly mechanical adventure with make-believe men."[60] British film critic Leslie Halliwell described it as "pretty good but overlong POW adventure with a tragic ending".[61] The Time magazine reviewer wrote in 1963: "The use of color photography is unnecessary and jarring, but little else is wrong with this film. With accurate casting, a swift screenplay, and authentic German settings, Producer-Director John Sturges has created classic cinema of action. There is no sermonizing, no soul probing, no sex. The Great Escape is simply great escapism".[62]

Modern appraisals

[edit]The Great Escape continues to receive acclaim from modern critics. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 94% based on 53 reviews. The site's critics consensus reads, "With its impeccably slow-building story and a cast for the ages, The Great Escape is an all-time action classic."[63]

In a 2006 poll in the United Kingdom, regarding the family film that television viewers would most want to see on Christmas Day, The Great Escape came in third, and was first among the choices of male viewers.[64] In an article for the British Film Institute, "10 great prisoner of war films", updated in August 2018, Samuel Wigley wrote that watching films like The Great Escape and the 1955 British film The Colditz Story, "for all their moments of terror and tragedy, is to delight in captivity in times of war as a wonderful game for boys, an endless Houdini challenge to slip through the enemy's fingers. Often based on true stories of escape, they have the viewer marvelling at the ingenuity and seemingly unbreakable spirit of imprisoned soldiers." He described The Great Escape as "the epitome of the war-is-fun action film", which became "a fixture of family TV viewing".[65]

Accolades

[edit]- Nominated Academy Award for Film Editing (Ferris Webster)

- Nominated Golden Globe Award for Best Picture

- Winner Moscow International Film Festival Best Actor (Steve McQueen)

- Nominated Moscow International Film Festival Grand Prix (John Sturges)

- Selected National Board of Review Top Ten Films of Year

- Nominated Writers Guild of America Best Written American Drama (James Clavell, W. R. Burnett) (Screenplay Adaptation)

- 19th place in AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills

Legacy

[edit]On 24 March 2014, the 70th anniversary of the escape, the RAF staged a commemoration of the escape attempt, with 50 serving personnel each carrying a photograph of one of the shot men.[66]

On 24 March 2019, the RAF held another event for the 75th anniversary of the escape. There was a screening of the film at London's Eventim Hammersmith Apollo, hosted by Dan Snow. The film was simulcast with other cinemas throughout the UK.[67]

Sequel

[edit]A fictional, made-for-television sequel, The Great Escape II: The Untold Story, was released in 1988, with Christopher Reeve, and directed by Jud Taylor (who played 2nd Lt. Goff in the 1963 film).[68] The film is not a true sequel, as it dramatizes the escape itself just as the original film does, although mostly using the real names of the individuals involved (whereas the original film fictionalized them and used composite characters). It depicts the search for the culprits responsible for the murder of the 50 Allied officers. Donald Pleasence appears in a supporting role as a member of the SS.[69]

In popular culture

[edit]- The Great Escape (1986) was released for the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum and DOS platforms, and shares a title and similar plot to the movie. The game follows an unnamed prisoner of war who has been interned in a POW camp somewhere in northern Germany in 1942.

- The Great Escape (2003) was released for Microsoft Windows, Xbox and PlayStation 2. The plotline follows that of the film, except there are also levels featuring some of the characters' first captures and early escape attempts, as well as a changed ending.

- The film is mentioned and heavily referenced in Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater.

- The films Chicken Run, Reservoir Dogs, the 1998 remake of The Parent Trap, Top Secret!, Charlie's Angels, The Tao of Steve, Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult, Inglourious Basterds, and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood all contain references or homages to the film.[69]

- Monty Python's Flying Circus, The Simpsons, Hogan's Heroes, Nash Bridges, Seinfeld, Get Smart, Fugget About It, Archer, Goodness Gracious Me, Shaun the Sheep, and Red Dwarf have all parodied or paid homage to the film.[69]

- The BritBox show Sister Boniface Mysteries referenced the film in the episode "St. George's Defence".

- Bernstein's Great Escape theme tune has been taken up by the Pukka Pies England Band, a small brass band who have played in the crowd at England football team matches since 1996.[70] They released an arrangement of the theme as a single for the 1998 FIFA World Cup and a newer version for UEFA Euro 2000.[71]

- Both the film and prison camp were showcased in the Amazon Prime series The Grand Tour.

- Japanese novelist Hiro Arikawa noted that she was greatly influenced by both The Great Escape and Gamera franchise, and took inspirations from them.[72]

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 1963

- The Bridge on the River Kwai, a similar film also released to critical acclaim

Notes

[edit]- ^ Bartlett calls Sedgwick "Bluey", an affectionate Australian slang term for a person with red hair; however, Sedgwick is often mistakenly referred to as "Louis" in some sources, including DVD subtitles.

References

[edit]- ^ Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-299-11440-4.

- ^ "The Great Escape (1963) - John Sturges; Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related". AllMovie. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Great Escape, premiere". The Times. London. June 20, 1963. p. 2.

- ^ "1963 year". Moscow International Film Festival. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Eder, Bruce (2009). "Review: The Great Escape". AllMovie. Macrovision Corporation. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ Adams, Derek (September 11, 2012). "The Great Escape". Time Out. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ Kim, Wook (February 16, 2012). "Top 10 Memorable Movie Motorcycles – The Great Escape". TIME. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ McKay, Sinclair (December 24, 2014). "The Great Escape: 50th anniversary". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Inside Tunnel "Harry"". Nova: Great Escape. PBS Online. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "The Great Escape". IMDb. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Wade, Robert J. (April 1951). "The Great Escape". Radio Age. Vol. 10, no. 3. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1999). Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide. New York: Signet. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-451-19714-6.

- ^ Kaufman, Michael T. (August 13, 1999). "John D. Lewis, 84, Pilot in 'The Great Escape'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Bishop, Patrick (August 30, 2015). "William Ash: The cooler king". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Foley, Brendan (April 29, 2014). "Bill Ash obituary". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "William Ash – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Whalley, Kirsty (November 10, 2008). "Escape artist's inspiring exploits". This is Local London. Newsquest Media Group / A Gannett Company. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (March 2, 1962). "'Mutiny' Director Find Make Deals: Bogarde in 'Living Room'; Du Pont Scion Plans Three". Los Angeles Times. p. C13.

- ^ Gill, Anton (2002). The Great Escape. London: Review. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7553-1038-8.

- ^ Vance 2000, p. 44: "Now sporting a huge, bushy moustache ... he set to work arranging the operations of the forgery department"

- ^ DVD extra.

- ^ Carroll, Tim (2004). The Great Escapers. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84018-904-9.

- ^ Rubin, Steven Jay (July 25, 2011). Combat Films: American Realism, 1945–2010 (2nd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8613-7. Archived from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hall, Allan (March 24, 2009). "British veterans mark Great Escape anniversary". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 20, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Riml, Walter (2013). Behind the scenes... The Great Escape. Helma Turk & Dr. Christian Riml. pp. 28, 44ff. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c Whistance, Don J. (2014). "The Great Escape Locations Site". thegreatescapelocations.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Riml (2013), p.110ff.

- ^ Riml (2013), p.58ff.

- ^ Biemann, Joachim (August 10, 2014). "The Great Escape". Eisenbahn im Film – Rail Movies (in German). Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c Warren, Jane (August 7, 2008). "The Truth About The Great Escape". Daily Express. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Rufford, Nick (February 13, 2009). "Video: The Great Escape, re-enacted". The Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ Rubin, Steve (1993). Return to 'The Great Escape' (Documentary). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ "The Great Escape is how Steve McQueen outfoxed studio lawyers and kept having fun | Hagerty Media". March 9, 2021. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Stone, Matt (2007). McQueen's Machines: The Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon. Minneapolis, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-7603-3895-7.

There's a chase sequence in there where the Germans were after [McQueen], and he was so much a better rider than they were, that he just ran away from them. And you weren't going to slow him down. So they put a German uniform on him, and he chased himself!

- ^ "Great Escape motorcycle goes on show". BBC News. November 2017. Archived from the original on July 31, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Wolter, Tim (2001). POW baseball in World War II. McFarland. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-7864-1186-3.

- ^ Brickhill, Paul, The Great Escape

- ^ "Canadians and the Great Escape". Canada at War. July 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 10, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Walters, Guy (2013). The Real Great Escape. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-0-593-07190-8.

- ^ Vance 2000, pp. 116–118.

- ^ The Great Escape: Heroes Underground documentary, available on The Great Escape DVD Special Edition.

- ^ Brissette, Pete (July 15, 2005). "Steve McQueen 40 Summers Ago..." Motorcycle.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Andrews (1976), p.49

- ^ Vance (2000), p.265

- ^ Read (2012), p.244

- ^ Andrews (1976), p.187-188

- ^ "Stalag Luft III: The Fifty". Pegasus Archive. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ Vance (2000), p.289

- ^ Hansen, Magne; Carlsen, Marianne Rustad (February 26, 2014). "Hollywood droppet nordmenn" [Hollywood dropped Norwegians]. NRK (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Paterson, Tony (March 25, 2009). "Veterans of the Great Escape visit old Stalag". The Independent. London. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on February 28, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Elmer Bernstein". The Daily Telegraph. August 20, 2004. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "Elmer Bernstein: The Great Escape". Classic FM. Global. August 23, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Lawson, Matt; MacDonald, Laurence E. (2018). 100 Greatest Film Scores. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-53810-368-5.

- ^ Wright, Joe (June 10, 2014). "Why England's band play the theme from 'The Great Escape' movie". Goal. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (May 28, 2016). "UKIP's use of Great Escape theme tune grates with composer's sons". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "THE GREAT ESCAPE (3 CD)". Intrada. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "The Great Escape – Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Lovell, Glenn (2008). Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 224.

- ^ "3rd Moscow International Film Festival (1963)". MIFF. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 8, 1963). "P.O.W.'s in 'Great Escape':Inmates of Nazi Camp Are Stereotypical – Steve McQueen Leads Snarling Tunnelers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ Walker, John (1997). Halliwell's Film and Video Guide. London: HarperCollins. p. 311. ISSN 1098-206X.

- ^ "Cinema: The Getaway". Time. July 19, 1963. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ^ "The Great Escape". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "TV classics are recipe for Christmas Day delight". Freeview. December 11, 2006. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ^ "10 great prisoner-of-war films". British Film Institute. April 18, 2013. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Robert (March 24, 2014). "'The Great Escape' commemorated in Poland". BBC News. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Great Escape with Dan Snow". RAF Benevolent Fund. November 20, 2018. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019.

- ^ "The Great Escape II: The Untold Story (TV Movie 1988)". IMDb. November 6, 1988. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Nixon, Rob (2008). "Pop Culture 101: The Great Escape". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ Walters, Mike. "Exclusive interview with The Pukka Pie England Band". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Official Charts Company – England Supporters' Band". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Daisuke Yoshida, 2017, 有川浩作品の原点は『ガメラ』と『大脱走』?, Da Vinci, Kadokawa Corporation

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrews, Allen (1976). Exemplary Justice. London: Harrap. ISBN 978-0-245-52775-3. Details the manhunt by the Royal Air Force's special investigations unit after the war to find and bring to trial the perpetrators of the "Sagan murders".

- Barris, Ted (2013). The Great Escape: A Canadian Story. Toronto: Thomas Allen. ISBN 978-1-77102-272-9.

- Brickhill, Paul (1950). The Great Escape. New York: Norton.

- Burgess, Alan (1990). The Longest Tunnel. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-1-55584-033-4.

- Fry, Helen (2020). MI9: A History of the Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30023-320-9.

- Hehner, Barbara (2004). The Tunnel King: The True Story of Wally Floody and the Great Escape. Toronto: Harper Trophy Canada.

- Hevesi, Dennis (April 22, 2012). "Alex Cassie of 'Great Escape' Dies at 95". The New York Times. p. 20.

- Müller, Jens (1946). Tre kom tilbake [Three returned]. Norway: Gyldendal. Memoir by the surviving Norwegian escapee.

- Polan, Dana (2021). Dreams of Flight: "The Great Escape" in American Film and Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520379305.

- Smith, Sydney (1968). 'Wings' Day. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-02494-5. Story of Wing Commander Harry "Wings" Day.

- Vance, Jonathan F. (2000). A Gallant Company: The True Story of the Man of "The Great Escape". New York: I Books. ISBN 978-0-7394-4242-5.

External links

[edit]- The Great Escape at IMDb

- The Great Escape at the TCM Movie Database

- The Great Escape at AllMovie

- The Great Escape at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Great Escape at Box Office Mojo

- James Garner Interview on the Charlie Rose Show Archived January 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (See 30:23–34:47 of video.)

- New publication with private photos of the shooting & documents of 2nd unit cameraman Walter Riml

- Photos of the filming

- The Great Escape locations

- Rob Davis web site on the Great Escape

- The Great Escape at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1963 films

- 1963 war films

- 1960s adventure drama films

- 1960s prison films

- 1960s war drama films

- Adventure films based on actual events

- American adventure drama films

- American epic films

- American prison drama films

- American war drama films

- Drama films based on actual events

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films scored by Elmer Bernstein

- Films about shot-down aviators

- Films about the United States Army Air Forces

- Films about the British Armed Forces

- Films about World War II crimes

- Films based on works by Paul Brickhill

- Films directed by John Sturges

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in 1943

- Films set in 1944

- Historical epic films

- Films about prison escapes

- Films with screenplays by James Clavell

- United Artists films

- 1960s war adventure films

- World War II films based on actual events

- World War II prisoner of war films

- American war adventure films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films

- Films about capital punishment

- English-language crime films

- English-language war adventure films

- English-language war drama films

- English-language adventure drama films