Tulsidas

Tulsidas | |

|---|---|

Picture of Tulsidas published in the Ramcharitmanas, by Sri Ganga Publishers, Gai Ghat, Benaras, 1949 | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Rambola Dubey 11 August 1511 |

| Died | 30 July 1623 (aged 111)[citation needed] |

| Spouse | Ratnavali |

| Parents |

|

| Known for | Composing the Ramcharitmanas and Hanuman Chalisa Reincarnation of Valmiki |

| Honors | Goswami, sant, Abhinavavālmīki, Bhaktaśiromaṇi |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Philosophy | Vishishtadvaita |

| Sect | Ramanandi Sampradaya |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Narharidas (Narharyanandacharya) |

Rambola Dubey (Hindi pronunciation: [rɑːməboːlɑː d̪ubeː]; 11 August 1511 – 30 July 1623[1]), known as Tulsidas (Sanskrit pronunciation: [tʊlsiːdaːsaː]),[2] was a Vaishnava (Ramanandi) Hindu saint and poet, renowned for his devotion to the deity Rama. He wrote several popular works in Sanskrit, Awadhi, and Braj Bhasha, but is best known as the author of the Hanuman Chalisa and of the epic Ramcharitmanas, a retelling of the Sanskrit Ramayana, based on Rama's life, in the vernacular Awadhi language.

Tulsidas spent most of his life in the cities of Banaras (modern Varanasi) and Ayodhya.[3] The Tulsi Ghat on the Ganges in Varanasi is named after him.[2] He founded the Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple in Varanasi, believed to stand at the place where he had the sight of the deity.[4] Tulsidas started the Ramlila plays, a folk-theatre adaptation of the Ramayana.[5]

He has been acclaimed as one of the greatest poets in Hindi, Indian, and world literature.[6][7][8][9] The impact of Tulsidas and his works on the art, culture and society in India is widespread and is seen today in the vernacular language, Ramlila plays, Hindustani classical music, popular music, and television series.[5][10][11][12][13][14]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Transliteration and etymology

[edit]The Sanskrit name of Tulsidas can be transliterated in two ways. Using the original Sanskrit, the name is written as Tulasīdāsa. Using the Hunterian transliteration system, it is written as Tulsidas or Tulsīdās reflecting the vernacular pronunciation (since the written Indian languages maintain the vestigial letters that are no longer pronounced). The lost vowels are an aspect of the Schwa deletion in Indo-Aryan languages and can vary between regions. The name is a compound of two Sanskrit words: Tulasī, which is an Indian variety of the basil plant considered auspicious by Vaishnavas (devotees of god Vishnu and his avatars like Rama),[15][16] and Dāsa, which means slave or servant and by extension, devotee.[17]

Sources

[edit]Tulsidas himself has given only a few facts and hints about events of his life in various works. Till late nineteenth century, the two widely known ancient sources on Tulsidas' life were the Bhaktamal composed by Nabhadas between 1583 and 1639, and a commentary on Bhaktamal titled Bhaktirasbodhini composed by Priyadas in 1712.[18] Nabhadas was a contemporary of Tulsidas and wrote a six-line stanza on Tulsidas describing him as an incarnation of Valmiki. Priyadas' work was composed around a hundred years after the death of Tulsidas and had eleven additional stanzas, describing seven miracles or spiritual experiences from the life of Tulsidas.[18] During the 1920s, two more ancient biographies of Tulsidas were published based on old manuscripts – the Mula Gosain Charit composed by Veni Madhav Das in 1630 and the Gosain Charit composed by Dasanidas (also known as Bhavanidas) around 1770.[18] Veni Madhav Das was a disciple and contemporary of Tulsidas and his work gave a new date for Tulsidas' birth. The work by Bhavanidas presented more narratives in greater detail as compared to the work by Priyadas. In the 1950s a fifth ancient account was published based on an old manuscript, the Gautam Chandrika composed by Krishnadatta Misra of Varanasi in 1624.[18] Krishnadatta Misra's father was a close companion of Tulsidas. The accounts published later are not considered authentic by some modern scholars, whereas some other scholars have been unwilling to dismiss them. Together, these five works form a set of traditional biographies on which modern biographies of Tulsidas are based.[18]

Incarnation of Valmiki

[edit]He is believed by many to be a reincarnation of Valmiki.[8] In the Hindu scripture Bhavishyottar Purana, the god Shiva tells his wife Parvati how Valmiki, who received a boon from Hanuman to sing the glory of Rama in vernacular language, will incarnate in future in the Kali Yuga (the present and last yuga or epoch within a cycle of four yugas).[19]

Devanagari IAST वाल्मीकिस्तुलसीदासः कलौ देवि भविष्यति । vālmīkistulasīdāsaḥ kalau devi bhaviṣyati । रामचन्द्रकथामेतां भाषाबद्धां करिष्यति ॥ rāmachandrakathāmetāṃ bhāṣābaddhāṃ kariṣyati ॥ O Goddess [Parvati]! Valmiki will become Tulsidas in the Kali age, and will compose this narrative of Rama in the vernacular language. Bhavishyottar Purana, Pratisarga Parva, 4.20.

Nabhadas writes in his Bhaktamal (literally, the Garland of bhakt or devotee) that Tulsidas was the re-incarnation of Valmiki in the Kali Yuga.[20][21][22][23] The Ramanandi sect believes that it was Valmiki himself who incarnated as Tulsidas in the Kali Yuga.[19]

According to a traditional account, Hanuman went to Valmiki numerous times to hear him sing the Ramayana, but Valmiki turned down the request saying that Hanuman being a monkey was unworthy of hearing the epic.[19] After the victory of Rama over Ravana, Hanuman went to the Himalayas to continue his worship of Rama. There he scripted a play version of the Ramayana called Mahanataka or Hanuman Nataka engraved on the Himalayan rocks using his nails.[24] When Valmiki saw the play written by Hanuman, he anticipated that the beauty of the Mahanataka would eclipse his own Ramayana. Hanuman was saddened at Valmiki's state of mind and, being a true bhakta without any desire for glory, Hanuman cast all the rocks into the ocean, some parts of which are believed to be available today as Hanuman Nataka.[19][24] After this, Valmiki was instructed by Hanuman to take birth as Tulsidas and compose the Ramayana in the vernacular.[19]

Early life

[edit]

Birth

[edit]Tulsidas was born on Saptami, the seventh day of Shukla Paksha, the bright half of the lunar Hindu calendar month Shraavana (July–August).[25][26] This correlates with 11 August 1511 of the Gregorian calendar. Although as many as three places are mentioned as his birthplace, most scholars identify the place with Soron, Kasganj district in Uttar Pradesh, a city on the banks of the river Ganga. In 2012 Soron was declared officially by the government of Uttar Pradesh as the birthplace of Tulsi Das.[1][19][27] His parents were Hulsi and Atmaram Dubey. Most sources identify him as a Saryupareen Brahmin of the Bharadwaj Gotra (lineage).[1][19][27] Tulsidas and Sir George Grierson give the year of his birth as Vikram 1568 (1511 CE).[1][28] These biographers include Ramkrishna Gopal Bhandarkar, Ramghulam Dwivedi, James Lochtefeld, Swami Sivananda and others.[1][25][27] The year 1497 appears in many current-day biographies in India and in popular culture. Biographers who disagree with this year argue that it makes the life span of Tulsidas equal 126 years, which in their opinion is unlikely if not impossible. In contrast, Ramchandra Shukla says that an age of 126 is not impossible for a Mahatma (great soul) like Tulsidas. The Government of India and provincial governments celebrated the 500th birth anniversary of Tulsidas in the year 2011 CE, according to the year of Tulsidas' birth in popular culture.[1]

Childhood

[edit]Legend goes that Tulsidas was born after staying in the womb for twelve months, he had all thirty-two teeth in his mouth at birth, his health and looks were like that of a five-year-old boy, and he did not cry at the time of his birth but uttered Rama instead.[27][29][30][31] He was therefore named Rambola (literally, he who uttered Rama), as Tulsidas himself states in Vinaya Patrika.[32] As per the Mula Gosain Charita, he was born under the Abhuktamūla constellation, which according to Hindu astrology causes immediate danger to the life of the father.[30][31][33][34] Due to the inauspicious astrological configurations at the time of his birth, on the fourth night he was sent away by his parents with Chuniya (some sources call her Muniya), a female house-help of Hulsi.[28][35][29] In his works Kavitavali and Vinayapatrika, Tulsidas attests to his family abandoning him after birth.[23][36][37][38]

Chuniya took the child to her village of Haripur and looked after him for five and a half years, after which she died.[35][31][33] Rambola was left to fend for himself as an impoverished orphan, and wandered from door to door for menial jobs and alms.[28][31] It is believed that the goddess Parvati assumed the form of a Brahmin woman and looked out for Rambola every day.[29][30] or alternately, the disciple of Anantacharya.[31][33] Rambola was given the Virakta Diksha (Vairagi initiation) with the new name of Tulsidas.[35] Tulsidas narrates the dialogue that took place during the first meeting with his guru in a passage in the Vinayapatrika.[28][32] When he was seven years old, his Upanayana ("sacred thread ceremony") was performed by Narharidas on the fifth day of the bright half of the month of Magha (January–February) at Ayodhya, a pilgrimage site related to Rama. Tulsidas started his learning at Ayodhya. After some time, Narharidas took him to a particular Varaha Kshetra Soron (a holy place with temple dedicated to Varaha – the boar avatar of Vishnu), where he first narrated the Ramayana to Tulsidas.[30] Tulsidas mentions this in the Ramcharitmanas.[39]

Devanagari IAST मैं पुनि निज गुर सन सुनी कथा सो सूकरखेत। maı̐ puni nija gura sana sunī kathā so sūkarakheta । समुझी नहिं तस बालपन तब अति रहेउँ अचेत॥ samujhī nahi̐ tasa bālapana taba ati raheu̐ aceta ॥ And then, I heard the same narrative from my Guru in a Sukarkhet (Varaha Kshetra) Soron. I did not understand it then, since I was totally without cognition in childhood. Ramcharitmanas 1.30 (ka).

Most authors identify the Varaha Kshetra referred to by Tulsidas with the Sookarkshetra is the Soron Varaha Kshetra in modern-day Kasganj,[30] Tulsidas further mentions in the Ramcharitmanas that his guru repeatedly narrated the Ramayana to him, which led him to understand it somewhat.[29]

Tulsidas later came to the sacred city of Varanasi and studied Sanskrit grammar, four Vedas, six Vedangas, Jyotisha and the six schools of Hindu philosophy over a period of 15–16 years from the guru Shesha Sanatana who was based at the Pancaganga Ghat in Varanasi.[35] Shesha Sanatana was a friend of Narharidas and a renowned scholar on literature and philosophy.[31][33][35][40]

Marriage and renunciation

[edit]There are two contrasting views regarding the marital status of Tulsidas. According to the Tulsi Prakash and some other works, Tulsidas was married to Ratnavali on the eleventh day of the bright half of the Kartik month (October–November) in Vikram 1604 (1561 CE).[30] Ratnavali was the daughter of Dinbandhu Pathak, a Brahmin of the Parashar gotra, who belonged to narayanpur village of Gonda district.[35][41][42] They had a son named Tarak who died as a toddler.[42] Once when Tulsidas had gone to a Hanuman temple, Ratnavali went to her father's home with her brother. When Tulsidas learned of this, he swam across the Sarju river in the night to meet his wife.[41] Ratnavali chided Tulsidas for this, and remarked that if Tulsidas was even half as devoted to God as he was to her body of flesh and blood, he would have been redeemed.[35][43] Tulsidas left her instantly and left for the holy city of Prayag. Here, he renounced the grihastha (householder's life) stage and became a sadhu (ascetic).[28][41]

Some authors consider the marriage episode of Tulsidas to be a later interpolation and maintain among that he was celibate.[31] These include Rambhadracharya, who cite two verses in the Vinayapatrika and Hanuman Bahuka that Tulsidas never married and was a sadhu from childhood.[29]

Later life

[edit]

Travels

[edit]After renunciation, Tulsidas spent most of his time at Varanasi, Prayag, Ayodhya, and Chitrakuta but visited many other nearby and far-off places. He travelled across India to many places, studying with different people, meeting saints and sadhus, and meditating.[44] The Mula Gosain Charita gives an account of his travels to the four pilgrimages of Hindus (Badrinath, Dwarka, Puri and Rameshwaram) and the Himalayas.[44][45] He visited Lake Manasarovar in current-day Tibet, where tradition holds he had Darshan (sight) of Kakabhushundi,[46] the crow who is one of the four narrators in the Ramcharitmanas.[47]

Darshan of Hanuman

[edit]Tulsidas hints at several places in his works, that he had met face to face with Hanuman and Rama.[44][48] The detailed account of his meetings with Hanuman and Rama are given in the Bhaktirasbodhini of Priyadas.[49] According to Priyadas' account, Tulsidas used to visit the woods outside Varanasi for his morning ablutions with a water pot. On his return to the city, he used to offer the remaining water to a certain tree. This quenched the thirst of a Preta (a type of ghost believed to be ever thirsty for water), who appeared to Tulsidas and offered him a boon.[49][50] Tulsidas said he wished to see Rama with his eyes, to which the Preta responded that it was beyond him. However, the Preta said that he could guide Tulsidas to Hanuman, who could grant the boon Tulsidas asked for. The Preta told Tulsidas that Hanuman comes everyday disguised as a leper to listen to his Katha, he is the first to arrive and last to leave.[44][49]

That evening Tulsidas noted that the first listener to arrive at his discourse was an old leper, who sat at the end of the gathering. After the Katha was over, Tulsidas quietly followed the leper to the woods. In the woods, at the spot where the Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple stands today,[44][51] Tulsidas firmly fell at the leper's feet, shouting "I know who you are" and "You cannot escape me".[44][49][50] At first the leper feigned ignorance but Tulsidas did not relent. Then the leper revealed his original form of Hanuman and blessed Tulsidas. When granted a boon, Tulsidas told Hanuman he wanted to see Rama face to face. Hanuman told him to go to Chitrakuta where he would see Rama with his own eyes.[44][46][49][50]

At the beginning of the Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas bows down to a particular Preta and asks for his grace (Ramcharitmanas, Doha 1.7). According to Rambhadracharya, this is the same Preta which led Tulsidas to Hanuman.[51]

Darshan of Rama

[edit]As per Priyadas' account, Tulsidas followed the instruction of Hanuman and started living in an Ashram at Ramghat in Chitrakoot Dham. One day Tulsidas went to perform the Parikrama (circumambulation) of the Kamadgiri mountain. He saw two princes, one dark and the other fair, dressed in green robes pass by mounted on horsebacks. Tulsidas was enraptured at the sight, however he could not recognise them and took his eyes off them. Later Hanuman asked Tulsidas if he saw Rama and his brother Lakshmana on horses. Tulsidas was disappointed and repentful. Hanuman assured Tulsidas that he would have the sight of Rama once again the next morning.[44][46][51] Tulsidas recalls this incident in a song of the Gitavali and laments how "his eyes turned his own enemies" by staying fixed to the ground and how everything happened in a trice.[44]

On the next morning, Wednesday, the new-moon day of Magha, Vikram 1607 (1551 CE) or 1621 (1565 CE) as per some sources, Rama again appeared to Tulsidas, this time as a child. Tulsidas was making sandalwood paste when a child came and asked for a sandalwood tilaka (a religious mark on the forehead). This time Hanuman gave a hint to Tulsidas and he had a full view of Rama. Tulsidas was so charmed that he forgot about the sandalwood. Rama took the sandalwood paste and put a tilaka himself on his forehead and Tulsidas' forehead before disappearing. This famous incidence is described in the verse "चित्रकूट के घाट पर हुई संतन की भीर तुलसीदास चन्दन घिसे तिलक देते रघुबीर".[44][45][46][51]

In a verse in the Vinayapatrika, Tulsidas alludes to a certain "miracle at Chitrakuta", and thanks Rama for what he did for him at Chitrakuta.[52] Some biographers conclude that the deed of Rama at Chitrakuta referred to by Tulsidas is the Darshan of Rama.[44][51]

Darshan of Yajnavalkya and Bharadvaja

[edit]In Vikram 1628 (1572 CE), Tulsidas left Chitrakuta for Prayag where he stayed during the Magh Mela (the annual festival in January). Six days after the Mela ended, he had the Darshan of the sages Yajnavalkya and Bharadvaja under a banyan tree.[46] In one of the four dialogues in the Ramcharitmanas, Yajnavalkya is the speaker and Bharadvaja the listener.[47] Tulsidas describes the meeting between Yajnavalkya and Bharadvaja after a Magha Mela festival in the Ramcharitmanas, it is this meeting where Yajnavalkya narrates the Ramcharitmanas to Bharadvaja.[53]

Attributed miracles

[edit]

Most stories about Tulsidas tend to be apocryphal, and have been carried forward by word of mouth. None of them were related by Tulsi himself, thus making it difficult to separate fact from lore and fiction. In Priyadas' biography, Tulsidas is attributed with the power of working miracles.[20][54] In one such miracle, he is believed to have brought a dead Brahmin back to life.[54][55][56][57] While the Brahmin was being taken for cremation, his widow bowed down to Tulsidas who addressed her as Saubhagyavati (a woman whose husband is alive).[55] The widow told Tulsidas her husband had just died, so his words could not be true.[56] Tulsidas said that the word has passed his lips and so he would restore the dead man to life. He asked everyone present to close their eyes and utter the name of Rama. On doing so, the dead man was brought back to life. Also one who was with him for a certain period of their life received moksha (spiritual liberation) from Maya (illusory world).[55][56]

Tulsidas was acclaimed in his lifetime to be a reincarnation of Valmiki, the composer of the original Ramayana in Sanskrit.[58]

In another miracle described by Priyadas, the Mughal Emperor Akbar summoned Tulsidas on hearing of his bringing back a dead man to life.[54][55][59][60] Tulsidas declined to go as he was too engrossed in creating his verses but he was later forcibly brought before Akbar and asked to perform a miracle, which Tulsidas declined by saying "It's a lie, all I know is Rama.". The emperor imprisoned Tulsidas at Fatehpur Sikri, saying "We will see this Rama.".[60] Tulsidas refused to bow to Akbar and created a verse in praise of Hanuman, the Hanuman Chalisa, and chanted it for forty days.[61][62][page needed] Suddenly an army of monkeys descended upon the town and wreaked havoc in all corners of Fatehpur Sikri,[61] entering each home and the emperor's harem, scratching people, and throwing bricks from ramparts.[60] An old Hafiz told the emperor that this was the miracle of the imprisoned Tulsidas.[59] The emperor fell at Tulsidas' feet, released him, and apologised.[57] Tulsidas stopped the menace of monkeys and asked the emperor to abandon the place. The emperor agreed and moved back to Delhi.[54][55][59][60] Ever since Akbar became a close friend of Tulsidas and he also ordered a firman that followers of Rama, Hanuman, and other Hindus, were not to be harassed in his kingdom.[63][page needed]

Priyadas narrates a miracle of Tulsidas at Vrindavan, when he visited a temple of Krishna.[57][64] When he began bowing down to the idol of Krishna, the Mahant of the temple named Parshuram decided to test Tulsidas. He told Tulsidas that he who bows down to any deity except their Ishta Devata (cherished form of divinity) is a fool, as Tulsidas' Ishta Devata was Rama.[64][65] In response, Tulsidas recited the following extemporaneously composed couplet:[57][64][65]

Devanagari IAST काह कहौं छबि आजुकि भले बने हो नाथ । kāha kahau̐ chabi ājuki bhale bane ho nātha । तुलसी मस्तक तब नवै धरो धनुष शर हाथ ॥ tulasī mastaka taba navai dharo dhanuṣa śara hātha ॥ O Lord, how shall I describe today's splendour, for you appear auspicious. Tulsidas will bow down his head when you take the bow and the arrow in your hands.

When Tulsidas recited this couplet, the idol of Krishna holding the flute and stick in hands changed to the idol of Rama holding the bow and arrow in hands.[57][64][65] Some authors have expressed doubts on the couplet being composed by Tulsidas.[57][64]

Literary life

[edit]

Tulsidas started composing poetry in Sanskrit in Varanasi on the Prahlada Ghat. Tradition holds that all the verses that he composed during the day, would get lost in the night. This happened daily for eight days. On the eighth night, Shiva – whose famous Kashi Vishwanath Temple is located in Varanasi – is believed to have ordered Tulsidas in a dream to compose poetry in the vernacular instead of Sanskrit. Tulsidas woke up and saw both Shiva and Parvati who blessed him. Shiva ordered Tulsidas to go to Ayodhya and compose poetry in Awadhi. Shiva also predicted that Tulsidas' poetry would fructify like the Sama Veda.[66] In the Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas hints at having the Darshan of Shiva and Parvati in both dream and awakened state.[67]

Tulsidas is also credited with having composed a number of wise sayings and dohas containing lessons for life. A popular maxim among them is: Don't go there, even if a mountain of gold is showered (Hindi: आवत ही हरषै नहीं, नैनन नहीं सनेह । तुलसी तहाँ न जाइये, चाहे कञ्चन बरसे मेघ ॥ सिया पति राम चन्द्र जी की जय, जय जय बजरंगबली ।।, romanized: Aawat hi harshai nahin, nainan nahin saneh. Tulsi tahan na jaiye, chahe kanchan barse megh, lit. 'A place where people are not happy or welcoming when you come, where their eyes have no affection for you').

Composition of Ramcharitmanas

[edit]In the year Vikram 1650 (1593 CE), Tulsidas started composing the Ramcharitmanas in Ayodhya on Sunday, Ramnavami day (ninth day of the bright half of the Chaitra month, which is the birthday of Rama). Tulsidas himself attests this date in the Ramcharitmanas .[68] He composed the epic over two years, seven months and twenty-six days, and completed the work in Vikram 1633 (1577 CE) on Vivaha Panchami, which commemorates the wedding day of Rama and Sita.[42][66]

Tulsidas came to Varanasi and recited the Ramcharitmanas to Shiva (Vishwanath) and Parvati (Annapurna) at the Kashi Vishwanath Temple. A popular legend goes that the Brahmins of Varanasi, who were critical of Tulsidas for having rendered the Sanskrit Ramayana in the Awadhi, decided to test the worth of the work. A manuscript of the Ramcharitmanas was kept at the bottom of pile of Sanskrit scriptures in the sanctum sanctorum of the Vishvanath temple in the night, and the doors of the sanctum sanctorum were locked. In the morning when the doors were opened, the Ramcharitmanas was found at the top of the pile. The words Satyam Shivam Sundaram (Sanskrit: सत्यं शिवं सुन्दरम्, lit. 'truth, auspiciousness, beauty') were inscribed on the manuscript with the signature of Shiva. The words were also heard by the people present.[66][69][70]

Per traditional accounts, some Brahmins of Varanasi were still not satisfied, and sent two thieves to steal the manuscript.[66][71] The thieves tried to break into the Ashram of Tulsidas, but were confronted by two guards with bows and arrows, of dark and fair complexion.[66] The thieves had a change of heart and came to Tulsidas in the morning to ask who the two guards were.[71] Believing that the two guards could be none other than Rama and Lakshmana, Tulsidas was aggrieved to discover that they were guarding his home at night.[66] He sent the manuscript of Ramcharitmanas to his friend Todar Mal, the finance minister of Akbar, and donated all his money.[66] The thieves were reformed and became devotees of Rama.[71]

Last compositions

[edit]Around Vikram 1664 (1607 CE), Tulsidas was afflicted by acute pain all over his body, especially in his arms. He then composed the Hanuman Bahuk, where he describes his bodily pain and suffering in several stanzas.[72] He was relieved of his pain after this composition. Later he was also afflicted by Bartod boils (Hindi: बरतोड़, furuncles caused by pulling out of the hair), which may have been the cause of his death.[72]

The Vinaypatrika is considered as the last compositions of Tulsidas, believed to be written when Kali Yuga started troubling him.[66] In this work of 279 stanzas, he beseeches Rama to give him Bhakti ("devotion"), and to accept his petition. Tulsidas attests in the last stanza of Vinaypatrika that Rama himself signed the manuscript of the work.[73] The 45th stanza of the Vinaypatrika is sung as the evening arti by many Hindus.[74]

Death

[edit]Tulsidas died at the age of 111 on 30 July 1623 (Shravan month of the year Vikram 1680) in Assi Ghat on the bank of the river Ganga. Traditional accounts and biographers do not agree on the exact date of his death.[75][76]

Works

[edit]Twelve works are widely considered by biographers to be written by Tulsidas, six major works and six minor works.[77] Based on the language of the works, they have been classified into two groups as follows–[78]

- Awadhi works – Ramcharitmanas, Ramlala Nahachhu, Barvai Ramayan, Parvati Mangal, Janaki Mangal and Ramagya Prashna.

- Braja works – Krishna Gitavali, Gitavali, Sahitya Ratna, Dohavali, Vairagya Sandipani and Vinaya Patrika.

Aside from the aforementioned works, Tulsidas is also known to have composed the Hanuman Chalisa, Hanuman Ashtak, Hanuman Bahuk, Bagrang Baan and Tulsi Satsai.[78]

Ramcharitmanas

[edit]Ramacharitamanas (रामचरितमानस, 1574–1576), "The Mānasa lake brimming over with the exploits of Lord Rāma"[79][80] is an Awadhi rendering of the Ramayana narrative.[25] It is the longest and earliest work of Tulsidas, and draws from various sources including the Ramayana of Valmiki, the Adhyatma Ramayana, the Prasannaraghava and Hanuman Nataka.[77] The work consists of around 12,800 lines divided into 1073 stanzas, which are groups of Chaupais separated by Dohas or Sorthas.[81] It is divided into seven books (Kands) like the Ramayana of Valmiki, and is around one-third of the size of Valmiki's Ramayana.[81] The work is composed in 18 metres which include ten Sanskrit meters (Anushtup, Shardulvikridit, Vasantatilaka, Vamshashta, Upajati, Pramanika, Malini, Sragdhara, Rathoddhata and Bhujangaprayata) and eight Prakrit metres (Soratha, Doha, Chaupai, Harigitika, Tribhangi, Chaupaiya, Trotaka and Tomara).[82][83][84] It is popularly referred to as Tulsikrit Ramayana, literally The Ramayana composed by Tulsidas.[85] The work has been acclaimed as "the living sum of Indian culture", "the tallest tree in the magic garden of medieval Indian poesy", "the greatest book of all devotional literature", "the Bible of Northern India", and "the best and most trustworthy guide to the popular living faith of its people." But, as he has said "The story of the lord is endless as are his glories" (Hindi: हरि अनंत हरि कथा अनंता।).[86]

Several manuscripts of the Ramcharitmanas are claimed to have been written down by Tulsidas himself. Grierson noted that two copies of the epic were said to have existed in the poet's own handwriting. One manuscript was kept at Rajapur, of which only the Ayodhyakand is left now, which bears watermarks. According to legend, the manuscript was stolen and thrown into Yamuna river. When the thief was being pursued, only the second book of the epic could be rescued.[87] Grierson wrote that the other copy was at Malihabad in Lucknow district, of which only one leaf was missing.[87] Another manuscript of the Ayodhyakanda claimed to be in the poet's own hand exists at Soron in Kasganj district, one of the places claimed to be Tulsidas' birthplace. One manuscript of Balakanda is found in Ayodhya. It is dated back to Samvat 1661, and claimed to have been corrected by Tulsidas.[88] Some other ancient manuscripts are found in Varanasi, including one in possession of the Maharaja of Benares that was written in Vikram 1704 (1647), twenty-four years after the death of Tulsidas.[87]

Other major works

[edit]The five major works of Tulsidas apart from Ramcharitmanas include:[78]

- Dohavali (दोहावली, 1581), literally Collection of Dohas, is a work consisting of 573 miscellaneous Doha and Sortha verses mainly in Braja with some verses in Awadhi. The verses are aphorisms on topics related to tact, political wisdom, righteousness and the purpose of life. 85 Dohas from this work are also found in the Ramcharitmanas, 35 in Ramagya Prashna, two in Vairagya Sandipani and some in Rama Satsai, another work of 700 Dohas attributed to Tulsidas.

- Sahitya ratna or ratna Ramayan (1608–1614), literally Collection of Kavittas, is a Braja rendering of the Ramayana, composed entirely in metres of the Kavitta family – Kavitta, Savaiya, Ghanakshari, and Chhappaya. It consists of 325 verses including 183 verses in the Uttarkand. Like the Ramcharitmanas, it is divided into seven Kands or books and many episodes in this work are different from the Ramcharitmanas.

- Gitavali (गीतावली), literally Collection of Songs, is a Braja rendering of the Ramayana in songs. All the verses are set to Ragas of Hindustani classical music and are suitable for singing. It consists of 328 songs divided into seven Kands or books. Many episodes of the Ramayana are elaborated while many others are abridged.

- Krishna Gitavali or Krishnavali (कृष्णगीतावली, 1607), literally Collection of Songs to Krishna, is a collection of 61 songs in honour of Krishna in Braja. There are 32 songs devoted to the childhood sports (Balalila) and Rasa Lila of Krishna, 27 songs form the dialogue between Krishna and Uddhava, and two songs describe the episode of disrobing of Draupadi.

- Vinaya Patrika (विनयपत्रिका), literally Petition of Humility, is a Braja work consisting of 279 stanzas or hymns. The stanzas form a petition in the court of Rama asking for Bhakti. It is considered to be the second best work of Tulsidas after the Ramcharitmanas, and is regarded as important from the viewpoints of philosophy, erudition, and eulogistic and poetic style of Tulsidas. The first 43 hymns are addressed to various deities and Rama's courtiers and attendants, and remaining are addressed to Rama.

Minor works

[edit]Minor works of Tulsidas include:[78]

- Barvai Ramayana (बरवै रामायण, 1612), literally The Ramayana in Barvai metre, is an abridged rendering of the Ramayana in Awadhi. The works consists of 69 verses composed in the Barvai metre, and is divided into seven Kands or books. The work is based on a psychological framework.

- Parvati Mangal (पार्वती मंगल), literally The marriage of Parvati, is an Awadhi work of 164 verses describing the penance of Parvati and the marriage of Parvati and Shiva. It consists of 148 verses in the Sohar metre and 16 verses in the Harigitika metre.

- Janaki Mangal (जानकी मंगल), literally The marriage of Sita, is an Awadhi work of 216 verses describing the episode of marriage of Sita and Rama from the Ramayana. The work includes 192 verses in the Hamsagati metre and 24 verses in the Harigitika metres. The narrative differs from the Ramcharitmanas at several places.

- Ramalala Nahachhu (रामलला नहछू), literally The Nahachhu ceremony of the child Rama, is an Awadhi work of 20 verses composed in the Sohar metre. The Nahachhu ceremony involves cutting the nails of the feet before the Hindu Samskaras (rituals) of Chudakarana, Upanayana, Vedarambha, Samavartana or Vivaha. In the work, events take place in the city of Ayodhya, so it is considered to describe the Nahachhu before Upanayana, Vedarambha and Samavartana.[89]

- Ramajna Prashna (रामाज्ञा प्रश्न), literally Querying the Will of Rama, is an Awadhi work related to both Ramayana and Jyotisha (astrology). It consists of seven Kands or books, each of which is divided into seven Saptakas or Septets of seven Dohas each. Thus it contains 343 Dohas in all. The work narrates the Ramayana non-sequentially, and gives a method to look up the Shakuna (omen or portent) for astrological predictions.

- Vairagya Sandipini (वैराग्य संदीपनी, 1612), literally Kindling of Detachment, is a philosophical work of 60 verses in Braja which describe the state of Jnana (realisation) and Vairagya (dispassion), the nature and greatness of saints, and moral conduct. It consists of 46 Dohas, 2 Sorathas and 12 Chaupai metres.

Popularly attributed works

[edit]The following four works are popularly attributed to Tulsidas–[78]

- Hanuman Chalisa (हनुमान चालीसा), literally, Forty Verses to Hanuman, is a text that sings the glory of Hanuman. It is written in the Awadhi vernacular and composed of 40 chaupais and two dohas. Popular belief holds the work to be authored by Tulsidas, and it contains his signature, though some authors do not think the work was written by him.[90] It is one of the most popularl read short religious texts in India, and is recited by millions of Hindus on Tuesdays and Saturdays.[90] It is believed to have been uttered by Tulsidas in a state of Samadhi at the Kumbh Mela in Haridwar.[78]

- Sankatmochan Hanumanashtak (संकटमोचन हनुमानाष्टक), literally Eight verses for Hanuman, the Remover of Afflictions, is an Awadhi work of eight verses in the Mattagajendra metre, devoted to Hanuman. It is believed to have been composed by Tulsidas on the occasion of the founding of the Sankatmochan Temple in Varanasi. The work is usually published along with Hanuman Chalisa.

- Hanuman Bahuka (हनुमान बाहुक), literally The Arm of Hanuman, is a Braja work of 44 verses believed to have been composed by Tulsidas when he suffered acute pain in his arms at an advanced age. Tulsidas describes the pain in his arms and also prays to Hanuman for freedom from the suffering. The work has two, one, five and 36 verses respectively in the Chhappaya, Jhulna, Savaiya and Ghanakshari metre.

- Tulsi Satsai (तुलसी सतसई), literally Seven Hundred Verses by Tulsidas, is a work in both Awadhi and Braja and contains 747 Dohas divided in seven Sargas or cantos. The verses are same as those in Dohavali and Ramagya Prashna but the order is different.

Tulsidas mentioned about destruction of Ram Janmabhumi temple by Mir Baqi in his work Tulsi Doha Shatak (lit. Hundred couplets of Tulsi) and the same was quoted by Rambhadracharya during the proceedings of the Ayodhya dispute in the Allahabad High court that influenced its judgment in 2010.[91][92]

Doctrine

[edit]The philosophy and principles of Tulsidas are found across his works, and are especially outlined in the dialogue between Kakbhushundi and Garuda in the Uttar Kand of the Ramcharitmanas.[93] Tulsidas' doctrine has been described as an assimilation and reconciliation of the diverse tenets and cultures of Hinduism.[94][95][96] At the beginning of the Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas says that his work is in accordance with various scriptures – the Puranas, Vedas, Upavedas, Tantra and Smriti.[97] Ram Chandra Shukla in his critical work Hindi Sahitya Ka Itihaas elaborates on Tulsidas' Lokmangal as the doctrine for social upliftment which made this great poet immortal and comparable to any other world littérateur.[citation needed]

Nirguna and Saguna Brahman

[edit]

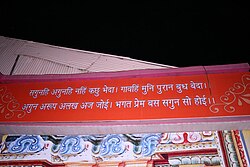

As per Tulsidas, the Nirguna Brahman (quality-less impersonal absolute) and Saguna Brahman (personal God with qualities) are one and the same. Both, Saguna (qualified Brahman) and Aguna (or Nirguna - unqualified Brahman) are Akath (unspeakable), Agaadh (unfathomable), Anaadi (without beginning, in existence since eternity) and Anupa (without parallel) (अगुन सगुन दुइ ब्रह्म सरूपा। अकथ अगाध अनादि अनूपा॥).[98] It is the devotion (Bhakti) of the devotee that forces the Nirguna Brahman which is quality-less, formless, invisible and unborn, to become Saguna Brahman with qualities. Tulsidas gives the example of water, snow and hail to explain this – the substance is the same in all three, but the same formless water solidifies to become hail or a mountain of snow – both of which have a form.[99][100] Tulsidas also gives the simile of a lake – the Nirguna Brahman is like the lake with just water, while the Saguna Brahman is a lake resplendent with blooming lotuses.[101][102] In the Uttar Kand of Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas describes in detail a debate between Kakbhushundi and Lomasa about whether God is Nirguna (as argued by Lomasa adhering to monism) or Saguna (as argued by Kakbhushundi adhering to dualism). Kakbhushundi repeatedly refutes all the arguments of Lomasa, to the point when Lomasa becomes angry and curses Kakbhushundi to be a crow. Lomasa repents later when Kakbhushundi happily accepts the curse but refuses to give up the Bhakti of Rama, the Saguna Brahman.[103][104] Though Tulsidas holds both aspects of God to be equal, he favours the qualified Saguna aspect and the devotees of the highest category in the Ramcharitmanas repeatedly ask for the qualified Saguna aspect of Rama to dwell in their mind.[105] Some authors contend from a few couplets in Ramcharitmanas and Vinay Patrika that Tulsidas has vigorously contradicted the denial of Avatar by Kabir.[106] In several of his works, Kabir had said that the actual Rama is not the son of Dasharatha. In the Balkand of Ramcharitmanas, Shiva tells Parvati – those who say that the Rama whom the Vedas sing of and whom the sages contemplate on is different from the Rama of Raghu's race are possessed by the devil of delusion and do not know the difference between truth and falsehood.[106][107] However, such allusions are based on interpretations of the text and do not hold much water when considered in the context of Ramcharitmanas. Tulsidas, in none of his works, has ever mentioned Kabir.

The name of Rama

[edit]

At the beginning of the Ramcharitmanas, there is a section devoted to the veneration of the name of Rama.[108] As per Tulsidas, repeating the name of Rama is the only means to attain God in the Kali age where the means suited for other ages like meditation, Karma, and Puja are ineffective.[109] He says in Kavitavali that his own redemption is because of the power, glory and majesty of the name of Rama.[110] In a couplet in the Gitavali, Tulsidas says that wishing for liberation without refuge in the name of Rama is like wishing to climb to the sky by holding on to the falling rain.[111] In his view, the name of Rama is greater than both Nirguna and Saguna aspects of God – it controls both of them and is illuminates both like a bilingual interpreter.[112] In a verse in the Dohavali, Tulsidas says that the Nirguna Brahman resides in his heart, the Saguna Brahman resides in his eyes and the name of Rama resides on his tongue, as if a radiant gemstone is kept between the lower and upper halves of a golden casket.[113] He holds that Rama is superior to all other names of God,[114] and argues that ra and ma being are the only two consonants that are written above all other consonants in the conjunct form in Sanskrit because they are the two sounds in the word Rama.[115]

Rama as Brahman

[edit]At several places in Tulsidas' works, Rama is seen to be the higher than Vishnu and not as an avatar of Vishnu, which is the general portrayal of Rama.[116][117][118]

In the episode of the delusion of Sati in Ramcharitmanas, Sati sees many a Shiva, Brahma and Vishnu serving Rama and bowing at his feet.[119] When Manu and Shatarupa perform penance, they crave to see that Supreme Lord "from a part of whose being emanate a number of Shivas, Brahmas and Vishnus."[120] Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva come to them many times tempting them with a boon, but Manu and Shatarupa do not stop their penance. They are finally satisfied only by the appearance of Rama, on whose left side is Sita, from a part of whom are born "countless Lakshmis, Umas (Parvatis) and Brahmanis (Sarasvatis)."[120] In the episode of marriage of Sita and Rama in Balkand, the trio of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva is present – Brahma is astounded as he finds nowhere anything that is his own handiwork, while Vishnu is enchanted with Lakhmi on seeing Rama.[121] In the Sundarkand, Hanuman tells Ravana that Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva can create, preserve and destroy by the might of Rama.[122] In the Lankakand, Tulsidas presents the universe as the cosmic form of Rama, in which Shiva is the consciousness, Brahma is the reason and Vishnu is his intelligence.[123] As per Tulsidas, Rama is not only an avatar, but also the source of avatars – Krishna is also an Avatar of Rama.[124] Thus, Tulsidas clearly considers Rama as supreme brahman and not an avatar of Vishnu.

In the opinion of Urvashi Soorati, the Rama of Tulsidas is an amalgamation of Vishnu who takes avatars, Vishnu in the abode of Ksheera Sagara, Brahman and the Para manifestation of the Pancharatra.[125] Macfie concludes that Tulsidas makes a "double claim", i.e. Rama is an incarnation of both Vishnu and Brahman.[126][127] In the words of Lutgendorf, Tulsidas' Rama is at once "Valmiki's exemplary prince, the cosmic Vishnu of Puranas, and the transcendent brahman of the Advaitins."[128]

Vedanta, World and Maya

[edit]In the Sundarkand of Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas says that Rama is knowable by Vedanta.[129][130]

As per Tulsidas, Rama is the efficient and material cause (Nimitta and Upadana) of the world, which is real since Rama is real.[131] In several verses of the Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas says that the animate and inanimate world is a manifestation of Rama, and the universe is the cosmic form of Rama. Authors interpret these verses to mean that the world is real according to Tulsidas, in keeping with the Vishishtadvaita philosophy of Ramanuja.[132][133][134] However, at some places in the Ramcharitmanas and Kavitavali, Tulsidas compares the world to a night or a dream and says it is Mithya (false or unreal). Some commentators interpret these verses to mean that in Tulsidas' opinion the world is unreal as per the Vivartavada doctrine of Adi Shankara, while some others interpret them to mean that the world is transient yet real as per the Satkhyativada doctrine of Ramananda.[135][136] Uday Bhanu Singh concludes that in Tulsidas' view, the world is essentially the form of Rama and appears to be different from Rama due to Maya. Its visible form is transient, which is what Tulsidas means by Mithya.[131]

In the Vinayapatrika, Tulsidas says that the world in itself is neither true (Satya), nor false (Asatya), nor both true and false together (Satyasatya) – one who casts aside all these three illusions, knows oneself. This has been interpreted to mean that as per Tulsidas, the entire world is a Lila of Rama.[137] At the beginning of the Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas performs Samasti Vandana (obeisance to all beings) in which he bows down to the world also, saying it is "pervaded by" or "born out of" Sita and Rama.[138][139][140] As per some verses in Ramcharitmanas and Vinaypatrika, when a Jiva (living being) knows the self, Maya, and Rama, it sees the world as being pervaded by Rama.[131]

In the Balkand episode of the marriage of the princes of Ayodhya with the princesses of Mithila, Tulsidas presents a metaphor in which the four brides are compared with the four states of consciousness – the waking state (Jagrat), sleep with dreams (Swapna), dreamless sleep (Sushupti) and the fourth self-conscious state (Turiya). The four grooms are compared with the presiding divinity (Vibhu) of the four states – Vishva, Taijasa, Prajna and Brahman. Tulsidas says as the four states of consciousness with their presiding divinities reside in the mind of a Jiva, so the four brides with their grooms are resplendent in the same pavilion.[141][142]

Tulsidas identifies Maya with Sita, the inseparable energy of Rama which takes avatar along with Rama.[143] In his view, Maya is of two types – Vidya and Avidya. Vidya Maya is the cause of creation and the liberation of Jiva. Avidya Maya is the cause of illusion and bondage of the Jiva. The entire world is under the control of Maya.[143] Maya is essentially the same but the two divisions are made for cognitive purposes, this view of Tulsidas is in accordance with Vaishnava teachers of Vedanta.[143]

Views on other Hindu deities

[edit]As per Tulsidas, there is no incompatibility between devotion to Rama and attachment to Shiva.[144][145] Tulsidas equates the Guru as an incarnation of Shiva,[146] and a considerable part of the Balkand of Ramcharitmanas is devoted to the narrative of Shiva including the abandonment of Sati, the penance of Parvati, the burning of Kamadeva and the marriage of Parvati and Shiva.[147] In addition, Tulsidas venerates the whole Hindu pantheon. The Ramcharitmanas begins with reverence of Ganesh, Sarasvati, Parvati, Shiva, the Guru, Valmiki and Hanuman.[146] At the beginning of the Vinayapatrika, he bows to Ganesh, Surya, Shiva, Devi, Ganga, Yamuna, Varanasi and Chitrakoot, asking them for devotion towards Rama.[148]

Bhakti

[edit]The practical end of all his writings is to inculcate bhakti addressed to Rama as the greatest means of salvation and emancipation from the chain of births and deaths, a salvation which is as free and open to men of the lowest caste.

Critical reception

[edit]

From his time, Tulsidas has been acclaimed by Indian and Western scholars alike for his poetry and his impact on the Hindu society. Tulsidas mentions in his work Kavitavali that he was considered a great sage in the world.[110] Madhusūdana Sarasvatī, one of the most acclaimed philosophers of the Advaita Vedanta tradition based in Varanasi and the composer of Advaitasiddhi, was a contemporary of Tulsidas. On reading the Ramcharitmanas, he was astonished and composed the following Sanskrit verse in praise of the epic and the composer.[51][149]

आनन्दकानने कश्चिज्जङ्गमस्तुल्सीतरुः ।

कविता मञ्जरी यस्य रामभ्रमरभूषिता ॥

ānandakānane kaścijjaṅgamastulsītaruḥ ।

kavitā mañjarī yasya rāmabhramarabhūṣitā ॥

In this place of Varanasi (Ānandakānana), there is a moving Tulsi plant (i.e., Tulsidas), whose branch of flowers in the form of [this] poem (i.e., Ramcharitmanas) is ever adorned by the bumblebee in the form of Rama.

Sur, a devotee of Krishna and a contemporary of Tulsidas, called Tulsidas as Sant Shiromani (the highest jewel among holy men) in an eight-line verse extolling Ramcharitmanas and Tulsidas.[150] Abdur Rahim Khankhana, famous Muslim poet who was one of the Navaratnas (nine-gems) in the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar, was a personal friend of Tulsidas. Rahim composed the following couplet describing the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas –[151][152]

रामचरितमानस बिमल संतनजीवन प्रान ।

हिन्दुवान को बेद सम जवनहिं प्रगट कुरान ॥

rāmacaritamānasa bimala santanajīvana prāna ।

hinduvāna ko beda sama javanahi̐ pragaṭa kurāna ॥

The immaculate Ramcharitmanas is the breath of the life of saints. It is similar to the Vedas for the Hindus, and it is the Quran manifest for the Muslims.

The historian Vincent Smith, the author of a biography of Tulsidas' contemporary Akbar, called Tulsidas "the greatest man of his age in India and greater than even Akbar himself".[20][153][154] The Indologist and linguist Sir George Grierson called Tulsidas "the greatest leader of the people after the Buddha" and "the greatest of Indian authors of modern times"; and the epic Ramcharitmanas "worthy of the greatest poet of any age."[20][153] The work Ramcharitmanas has been called "the Bible of North India" by both nineteenth century Indologists including Ralph Griffith, who translated the four Vedas and Valmiki's Ramayana into English, and modern writers.[25][155][156] Mahatma Gandhi held Tulsidas in high esteem and regarded the Ramcharitmanas as the "greatest book in all devotional literature".[157] The Hindi poet Suryakant Tripathi 'Nirala' called Tulsidas "the most fragrant branch of flowers in the garden of the world's poetry, blossoming in the creeper of Hindi".[9] Nirala considered Tulsidas to be a greater poet than Rabindranath Tagore, and in the same league as Kalidasa, Vyasa, Valmiki, Homer, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and William Shakespeare.[9] Hindi litterateur Hazari Prasad Dwivedi wrote that Tulsidas established a "sovereign rule on the kingdom of Dharma in northern India", which was comparable to the impact of Buddha.[158] Edmour J. Babineau, author of the book Love and God and Social Duty in Ramacaritmanasa, says that if Tulsidas was born in Europe or the Americas, he would be considered a greater personality than William Shakespeare.[159] In the words of the archaeologist F. R. Allchin, who translated Vinaypatrika and Kavitavali into English,[160][161] "for people of a large part of North India Tulsidas claims reverence comparable to that accorded to Luther as translator of the Bible into the native German". Allchin also mentions that the work Ramcharitmanas has been compared to not only the Ramayana of Valmiki, but the Vedas themselves, the Bhagavad Gita, the Quran and the Bible.[22] Ernest Wood in his work An Englishman Defends Mother India considered the Ramcharitmanas to be "superior to the best books of the Latin and Greek languages."[154] Tulsidas is also referred to as Bhaktaśiromaṇi, meaning the highest jewel among devotees.[162]

Specifically about his poetry, Tulsidas has been called the "emperor of the metaphor" and one who excels in similes by several critics.[163][164][165] The Hindi poet Ayodhyasingh Upadhyay 'Hariaudh' said of Tulsidas –[166][167]

कविता करके तुलसी न लसे

कविता लसी पा तुलसी की कला ।

kavitā karake tulasī na lase

kavitā lasī pā tulasī kī kalā ।

Tulsidas did not shine by composing poetry, rather it was Poetry herself that shone by getting the art of Tulsidas.

The Hindi poet Mahadevi Varma said commenting on Tulsidas that in the turbulent Middle Ages, India received enlightenment from Tulsidas. She further went on to say that the Indian society as it exists today is an edifice built by Tulsidas, and the Rama as we know today is the Rama of Tulsidas.[168]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f pp. 23–34.[citation needed]

- ^ a b de Bruyn, Pippa; Bain, Dr. Keith; Allardice, David; Joshi, Shonar (2010). Frommer's India. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States of America: John Wiley and Sons. p. 471. ISBN 9780470602645.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 857, quoting Mata Prasad Gupta: Although he paid occasional visits to several places of pilgrimage associated with Rama, his permanent residence was in Kashi.

- ^ Callewaert, Winand M.; Schilder, Robert (2000). Banaras: Vision of a Living Ancient Tradition. New Delhi, India: Hemkunt Press. p. 90. ISBN 9788170103028.

- ^ a b Handoo 1964, p. 128: ... this book ... is also a drama, because Goswami Tulasidasa started his Ram Lila on the basis of this book, which even now is performed in the same manner everywhere.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. xii: He is not only the supreme poet, but the unofficial poet-laureate of India.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. xix: Of Tulasidasa's place among the major Indian poets there can be no question: he is as sublime as Valmiki and as elegant as Kalidasa in his handling of the theme.

- ^ a b Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism (Encyclopedia of World Religions) (Hardbound, Illustrated ed.). New York City, United States of America: Infobase Publishing. p. 456. ISBN 9780816054589.

It can be said without reservation that Tulsidas is the greatest poet to write in the Hindi language. Tulsidas was a Brahmin by birth and was believed to be a reincarnation of the author of the Sanskrit Ramayana, Valmikha singh.

- ^ a b c Sahni, Bhisham (2000). Nilu, Nilima, Nilofara (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd. pp. 78–80. ISBN 9788171789603.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 11: ... – scores of lines from the Rāmcaritmānas have entered folk speech as proverbs – ...

- ^ Mitra, Swati (5 May 2002). Good Earth Varanasi City Guide. New Delhi, India: Eicher Goodearth Publications. pp. 216. ISBN 9788187780045.

- ^ Subramanian, Vadakaymadam Krishnier (2008). Hymns of Tulsidas. New Delhi, India: Abhinav Publications. pp. 181. ISBN 9788170174967.

Famous classical singers like Paluskar, Anoop Jalota and MS Subbulakshmi have popularised Tulsidas's hymns among the people of India.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 411: The hottest-selling recording in the thriving cassette stalls of Banaras in 1984... was a boxed set of eight cassettes comprising an abridged version of the Manas sung by the popular film singer Mukesh... it is impossible to say how many of the sets were sold, but by 1984 their impact was both visible and audible. One could scarcely attend a public or private religious function in Banaras that year without hearing, over the obligatory loudspeaker system, the familiar strains of Murli Manohar Svarup's orchestration and Mukesh's mellifluous chanting.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, pp. 411–412: On 25 January 1987, a new program premiered on India's government-run television network, Doordarshan... it was the first time that television was used to present a serialized adaption of a religious epic. The chosen work was the Ramayan and the major source for the screenplay was the Manas. Long before the airing of the main story concluded on 31 July 1988, the Ramayan had become the most popular program ever shown on Indian television, drawing an estimated one hundred million viewers and generating unprecedented advertising revenues. Throughout much of the country, activities came to a halt on Sunday mornings and streets and bazaars took on a deserted look, as people gathered before their own and neighbors' TV sets.... The phenomenal impact of the Ramayan serial merits closer examination than it can be given here, but it is clear that the production and the response it engendered once again dramatized the role of the epic as a principal medium not only for individual and collective religious experience but also for public discourse and social and cultural reflection.

- ^ Flood, Gavin D. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism (Illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey, United States of America: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 331. ISBN 9780631215356.

- ^ Simoons, Frederick J. (1998). Plants of life, plants of death (1st ed.). Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America: Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 7–40. ISBN 9780299159047.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Sir Monier (2005) [1899]. A Sanskrit-English dictionary: etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages. New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 477. ISBN 9788120831056.

- ^ a b c d e Lutgendorf, Philip (1994). "The quest for the legendary Tulsidās". In Callewaert, Winand M.; Snell, Rupert (eds.). According to Tradition: Hagiographical Writing in India. Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 65–85. ISBN 9783447035248.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rambhadracharya 2008, p. xxv.

- ^ a b c d Lutgendorf 1991, pp. 29.

- ^ Growse 1914, p. v.

- ^ a b Prasad 2008, p. xix.

- ^ a b Lamb 2002, p. 38

- ^ a b Kapoor, Subodh, ed. (2004). A Dictionary of Hinduism: Including Its Mythology, Religion, History, Literature and Pantheon. New Delhi, India: Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 159. ISBN 9788177558746.

- ^ a b c d Lochtefeld, James G. (2001). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. New York City, United States of America: Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 558–559. ISBN 9780823931804.

- ^ Gita Press Publisher 2007, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Sivananda, Swami. "Goswami Tulsidas By Swami Sivananda". Sivananda Ashram, Ahmedabad. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Ralhan 1997 pp. 187–194.

- ^ a b c d e Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. xxvi–xxix.

- ^ a b c d e f Gita Press Publisher 2007, pp. 25–27.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tripathi 2004, pp. 47–50.

- ^ a b Poddar 1997, pp. 112–113 (Stanza 76).

- ^ a b c d Pandey 2008, pp. 34–44.

- ^ Bhat, M. Ramakrishna (1988). Fundamentals of Astrology (3rd ed.). New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 52. ISBN 9788120802766.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shukla 2002, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Indradevnarayan 1996, pp. 93–94, 101–102 (Quatrains 7.57, 7.73).

- ^ Poddar 1997, pp. 285–286, 337–338 (Stanzas 227, 275).

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 80.

- ^ Ralhan 1997 pp. 197–207.

- ^ a b c Pandey 2008, pp. 44–49.

- ^ a b c Tripathi 2004, pp. 51–55

- ^ Pandey 2008 p. 49: As per the Mula Gosain Charita, Ratnavali said, "हाड़ माँस की देह मम तापर जितनी प्रीति। तिसु आधी जो राम प्रति अवसि मिटिहिं भवभीति॥." Acharya Ramchandra Shukla gives a slightly different version as "अस्थि चर्म मय देह मम तामे जैसी प्रीति। तैसी जो श्री राम मँह होत न तो भवभीति॥""

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ralhan 1997, pp. 194–197.

- ^ a b Shukla 2002, pp. 30–32.

- ^ a b c d e Gita Press Publisher 2007, pp. 27–29.

- ^ a b Lutgendorf 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Pradas 2008, p. 878, quoting J. L. Brockington: ... for in his more personal Vinayapatrika Tulasi alludes to having visions of Rama.

- ^ a b c d e Lutgendorf 1991, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Growse 1914, p. ix.

- ^ a b c d e f Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. xxix–xxxiv.

- ^ Poddar 1997, pp. 338–339 (Stanza 276).

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 48–49 (Ramcharitmanas 1.44.1–44.6)

- ^ a b c d Macfie 2004, p. xxiv

- ^ a b c d e Growse 1914, p. ix–x.

- ^ a b c Mishra 2010, pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b c d e f Singh 2008, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Mishra 2010, p. 28–32

- ^ a b c d Pinch, William R. (2006). Warrior ascetics and Indian empires. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 9780521851688.

- ^ a b Hanuman: an introduction by Devdutt Pattanaik. Vakils, Feffer and Simons. 2001. p. 122. ISBN 9788187111474.

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip (2007). Hanuman's tale: the messages of a divine monkey. Oxford University Press.

- ^ The Din-I-Ilahi, or, The religion of Akbar by Makhan Lal Roy Choudhury. Oriental Reprint, 1985

- ^ a b c d e Mishra 2010, pp. 37–38

- ^ a b c "जब श्रीकृष्ण को बनना पड़ा श्रीराम" [When Shri Krishna had to become Shri Rama] (in Hindi). Jagran Yahoo. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gita Press Publisher 2007, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 66 (Ramcharitmanas 1.15).

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 38–39: संबत सोरह सै एकतीसा। करउँ कथा हरि पद धरि शीसा॥ नौमी भौम बार मधु मासा। अवधपुरी यह चरित प्रकासा॥ जेहि दिन राम जनम श्रुति गावहिं। तीरथ सकल इहाँ चलि आवहिं॥ (Ramcharitmanas, 1.34.4–1.34.6)

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, pp. 9–10

- ^ Lamb 2002, p. 39

- ^ a b c Macfie 2004, pp. xxiii–xxiv.

- ^ a b Pandey 2008, pp. 51–58.

- ^ Poddar 1997, pp. 341–342 (Stanza 279): मुदित माथ नावत बनी तुलसी अनाथकी परी रघुनाथ हाथ सही है (Tulsidas bows his head with elation, the orphan has been redeemed, for the signature of Rama's hand has been made [on the Vinaypatrika]).

- ^ Poddar 1997, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Pandey 2008, pp. 58–60: संवत् सोरह सै असी असी गंग के तीर। श्रावण शुक्ला सत्तमी तुलसी तज्यो शरीर॥ quoting Mata Prasad Gupta, and also संवत् सोरह सै असी असी गंग के तीर। श्रावण श्यामा तीज शनि तुलसी तज्यो शरीर॥ quoting the Mula Gosain Charita.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. xxxiv: संवत् सोरह सै असी असी गंग के तीर। श्रावण शुक्ला तीज शनि तुलसी तज्यो शरीर॥

- ^ a b Lutgendorf 1991, pp. 3–12.

- ^ a b c d e f Pandey 2008, pp. 54–58

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Olive Classe (2000), Encyclopedia of literary translation into English: M-Z, Volume 2, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-884964-36-7, "... Rāmcāritmānas, composed in the Avadhi dialect of Hindi, is an epic of some 13,000 lines divided into seven kandas or 'books.' The word mānas (which Hindi speakers often use as an abbreviation of the longer title) alludes to a sacred lake in the Himalayas, and so the title may be rendered 'the divine lake of Ram's deeds' ..."

- ^ a b Lutgendorf 1991, pp. 13–18.

- ^ Rambhadracharya, Swami (December 2010). Sushil, Surendra Sharma (ed.). "श्रीरामचरितमानस में वृत्त मर्यादा" [Prosodic propriety in Ramcharitmanas]. Shri Tulsi Peeth Saurabh (in Hindi). 14 (7). Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India: Shri Tulsi Peeth Seva Nyas: 15–25.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. xix, footnote 3.

- ^ Miśra, Nityānanda (14 August 2011). "Metres in the Rāmacaritamānasa" (PDF). Shri Tulsi Peeth Seva Nyas. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Mishra 2010, Title.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Prasad 2008, p. 850, quoting George Grierson.

- ^ Lyall 1911, p. 369.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 44.

- ^ a b Lutgendorf 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Jain, Sandhya (18 August 2020). "Tulsidas' testimony". www.dailypioneer.com. Daily Pioneer. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

"Babur came with sword in hand in the summer months of Vikram Samvat 1585 (1528 AD) and created havoc (anarth). The beautiful Ram Janmabhumi temple was ruined and a mosque built; Tulsi felt aggrieved (Tulsi kinhi hai)." Further, Mir Baqi destroyed the temple and the murtis of Ram Darbar (family of infant Ram) as a broken-hearted Tulsi cried for protection (Trahi trahi Raghuraj). Tulsi continued, "Where there was a temple on Ram's birthplace, in the middle of Awadh, Mir Baqi built a mosque." In Kavitavali, Tulsidas laments, where are the ascetics (dhoot, avadhoot), the Rajputs and the weavers? He expresses detachment from society. Tulsi, he avers, is devoted to Ram, will eat by begging, will sleep in mosque (masit mein saibo).

- ^ TOI Lifestyle Desk, ed. (23 January 2024). "Guru Rambhadracharya, Who Deposed On Behalf Of Lord Ram In Allahabad HC". Times of India. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. xiii–xv.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. xv: Probably the most marvellous thing about the life of Tulasidasa... is his capacity for assimilating diverse tenets, Vaishnava, Shaiva, Advaita, Sankhya, etc.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. xx: ... the Ramacharitamanasa interprets the period allegorically and from the Vaishnavite angle of a poet who "attempted to reconcile the Advaita Vedanta point of view with the Ramaite teachings of Ramananda's disciples".

- ^ Dwivedi 2008, p. 99: उनका सारा काव्य समन्वय की विराट चेष्टा है। लोक और शास्त्र का समन्वय, गार्हस्थ्य और वैराग्य का समन्वय, भक्ति और ज्ञान का समन्वय, भाषा और संस्कृत का समन्वय, निर्गुण और सगुण का समन्वय, कथा और तत्त्व ज्ञान का समन्वय, ब्राह्मण और चांडाल का समन्वय, पांडित्य और अपांडित्य का समन्वय – रामचरितमानस शुरु से आखिर तक समन्वय का काव्य है।

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 3: नानापुराणनिगमागमसम्मतं ...

- ^ Ramcharitmanas 1.23.1

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 149 (Ramcharitmanas 1.116.1–1.116.3): सगुनहि अगुनहि नहिं कछु भेदा। गावहिं मुनि पुरान बुध बेदा॥ अगुन अरूप अलख आज जोई। भगत प्रेम बश सगुन सो होई॥ जो गुन रहित सगुन सोइ कैसे। जल हिम उपल बिलग नहिं जैसे॥.

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 647 (Ramcharitmanas 4.17.2): फूले कमल सोह सर कैसे। निर्गुन ब्रह्म सगुन भए जैसे॥.

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 767–771.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 943–948 (Ramcharitmanas 7.111.1–7.114.7)

- ^ Dwivedi 2009, p. 132.

- ^ a b Singh 2008, pp. 200–201: उन्होंने उत्तेजित होकर कबीर के मत का ओजस्वी शब्दों में प्रतिकार किया ... कबीर का अवतार विरोधी कथन था ... तुलसी ने "आना" और "अंधा" शब्दों को लक्ष्य करके शिव से मुँहतोड़ उत्तर दिलाया ...

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 24–32.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 31–32 (Ramcharitmanas 1.27.3, 1.27.7): ध्यान प्रथम जुग मख बिधि दूजे। द्वापर परितोषत प्रभु पूजे॥ ... नहिं कलि करम न भगति बिबेकू। राम नाम अवलंबन एकू॥

- ^ a b Indradevnarayan 1996, pp. 100–101 (Quatrain 7.72): राम नाम को प्रभाउ पाउ महिमा प्रताप तुलसी सो जग मनियत महामुनि सों। (It is the power, glory and majesty of the name of Rama due to which the likes of Tulsidas are considered like great sages in the world).

- ^ Poddar 1996, p. 14 (Dohavali 20): राम नाम अवलंब बिनु परमारथ की आस। बरषत बारिद बूँद गहि चाहत चढ़न अकास॥

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 27–28 (Ramcharitmanas 1.21.8, 1.23.3): अगुन सगुन बिच नाम सुसाखी। उभय प्रबोधक चतुर दुभाखी॥ ... मोरे मत बड़ नाम दुहूँ ते। किए जेहिं जुग निज बस निज बूते॥

- ^ Poddar 1996, p. 10–11 (Dohavali 7): हियँ निर्गुन नयननि सगुन रसना राम सुनाम। मनहुँ पुरट संपुट लसत तुलसी ललित ललाम॥

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 623–624 (Ramcharitmanas 3.44.7–3.44): जद्यपि प्रभु के नाम अनेका। श्रुति कह अधिक एक तें एका॥ राम सकल नामन्ह ते अधिका। होउ नाथ अघ खग गन बधिका॥ राका रजनी भगति तव राम नाम सोइ सोम। अपर नाम उडगन बिमल बसहुँ भगत उर ब्योम॥ एवमस्तु मुनि सन कहेउ कृपासिंधु रघुनाथ। तब नारद मन हरष अति प्रभु पद नायउ माथ॥

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 26 (Ramcharitmanas 1.20): एक छत्र एक मुकुटमनि सब बरनन पर जोउ। तुलसी रघुबर नाम के बरन बिराजत दोउ॥

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 875, quoting Frank Whaling: Theologically, Tulasidasa continues the process, begun in the Adhyatma [Ramayana], whereby Rama is seen to be higher than Vishnu. We see this in Tulasi's stress upon the Name of Rama; we see it also in Tulasi's assertions that Rama is Brahman whereas Vishnu is not. ... Tulasi uses the word Rama in the sense of God, ... The usual comparison has been between Rama and Christ, but perhaps an apter comparison is between Rama and the Christian God, for in terms of Ramology, Rama is equivalent to God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

- ^ Bakker, Freek L. (2009). The challenge of the silver screen: an analysis of the cinematic portraits of Jesus, Rama, Buddha and Muhammad: Volume 1 of Studies in religion and the arts (Illustrated ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: BRILL. p. 123. ISBN 9789004168619.

It is clear that Rama transcends Vishnu in the Manas. He is Brahman and becomes God in any conceivable form ... It is significant that at the end of Tulsidas' work Rama does not return to his form as Vishnu but continues to rule over Ayodhya.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 180

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 45 (Ramcharitmanas 1.45.7–8).

- ^ a b Prasad 2008, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 210, 212 (Ramcharitmanas 1.314.8, 1.317.3).

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 549 (Ramcharitmanas 5.21.3).

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 589 (Ramcharitmanas 6.15 Ka).

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 230: तुलसीदास द्वारा किया गया इतिवृत्त वर्णन तीन कथानायकों पर केन्द्रित है – राम, शिव और कृष्ण। ... राम अवतार मात्र नहीं हैं, वे अवतारी भी हैं। कृष्ण राम के ही अवतार हैं। अतः उनकी अवतार-लीला भी रूपांतर से राम की ही अवतार लीला है।

- ^ Soorati, Urvashi (2008). कबीर: जीवन और दर्शन [Kabir: Life and Philosophy] (in Hindi). Allahabad, India: Lokbharti Publication. p. 176. ISBN 9788180312397.

ऐसा प्रतीत होता है कि 'उपास्य ब्रह्म राम' अवतार ग्रहण करने वाले विष्णु, क्षीरशायी विष्णु, ब्रह्म और पांचरात्र के 'परविग्रह' – इन सबका समन्वित रूप है।

- ^ Macfie 2004, p. 93: The poet's claim is that he is not only an incarnation of Vishnu, the second member of the Triad, but of Brahm, the uncreated, invisible, all-pervading Brahm, the Supreme Spirit of the universe, who has taken on himself a visible form.

- ^ Macfie 2004, Chapter IX: Rama, the incarnation of Vishnu, and of Brahm, the Supreme God, pp. 93–160.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 533.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 660

- ^ a b c Singh 2008, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Shukla 2002, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 510, 588–589.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 632–633, 728–729.

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 82, 307, 500.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, pp. 101, 377–378, 621.

- ^ Poddar 1997, pp. 144–145 (Stanza 111).

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. xi.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 221.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2008, p. 275.

- ^ a b c Singh 2008, p. 272.

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. 579 (Ramcharitmanas 6.2): Those who are devoted to Shankara and are hostile to me, and those who are opposed to Shiva but would fain be my servants, shall have their abode in the deepest hell for a full aeon.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 48: I have noted that a major theme of Tulsi's epic is the compatibility of the worship of Ram/Vishnu with that of Shiva.

- ^ a b Prasad 2008, p. 1

- ^ Prasad 2008, pp. 40–77 (Ramcharitmanas 1.48–1.104).

- ^ Poddar 1997, pp. 1–24 (Stanzas 1–24).

- ^ Shukla 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Shukla 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Shukla 2002, p. 35.

- ^ Pandey 2008, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Dwivedi 2009, p. 125.

- ^ a b Prasad 2008, p. xxiv.

- ^ Growse 1914, p. Cover: "The Ramayan of Tulsi Das is more popular and more honoured by the people of North-Western provinces than the Bible is by the corresponding classed in England", Griffith.

- ^ Macfie 2004, p. vii: The choice of the subtitle is no exaggeration. The book is indeed the Bible of Northern India.

- ^ Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1927). "X. Glimpses of Religion". The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Ahmedabad, India: Navajivan Trust. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

Today I regard the Ramayana of Tulasidas as the greatest book in all devotional literature.

- ^ Dwivedi, Hazari Prasad (September 2008). हिंदी साहित्य की भूमिका [Introduction to Hindi literature] (in Hindi). Rajkamal Prakashan. p. 57. ISBN 9788126705795. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

बुद्धदेव के बाद उत्तर भारत के धार्मिक राज्य पर इस प्रकार एकच्छत्र अधिकार किसी का न हुआ (Nobody since Buddha had established such a sovereign rule on the kingdom of Dharma in northern India.)

- ^ Pandey 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Amazon.com: Petition To Ram Hindi Devotional Hymns: F R Allchin: Books. Allen & Unwin. January 1966. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Amazon.com: Kavitavali: Tulsidas, F R Allchin: Books. ISBN 0042940117.

- ^ Shukla 2002, p. 27

- ^ Prasad 2008, p. xx: Kalidasa's forte is declared to lie in similes, Tulasidasa excels in both metaphors and similes, especially the latter.

- ^ Pandey, Sudhaker (1999). रामचरितमानस (साहित्यिक मूल्यांकन) [Ramcharitmanas (Literary evaluation)] (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 9788171194391.

स्वर्गीय दीनजी तुलसीदास को रूपकों का बादशाह कहा करते थे।

- ^ Misra, Ramaprasada (1973). विश्वकवि तुलसी और उनके काव्य [The Universal Poet Tulasi and his works] (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Surya Prakashan.

कालिदास उपमा के सम्राद हैं; तुलसीदास रूपक के सम्राट हैं।

- ^ Pandey 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 339.

- ^ Pandey 2008, p. 11: इस सन्दर्भ में सुप्रसिद्ध कवयित्री महादेवी वर्मा का कथन द्रष्टव्य है – हमारा देश निराशा के गहन अन्धकार में साधक, साहित्यकारों से ही आलोक पाता रहा है। जब तलवारों का पानी उतर गया, शंखों क घोष विलीन हो गया, तब भी तुलसी के कमंडल का पानी नहीं सूखा ... आज भी जो समाज हमारे सामने है वह तुलसीदास का निर्माण है। हम पौराणिक राम को नहीं जानते, तुलसीदास के राम को जानते हैं।

References

[edit]- Dwivedi, Hazari Prasad (2008). हिन्दी साहित्य की भूमिका [Introduction to Hindi Literature] (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9788126705795.

- Dwivedi, Hazari Prasad (2009). हिन्दी साहित्य: उद्भव और विकास [Hindi Literature: Beginnings and Developments] (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9788126700356.

- Growse, Frederic Salmon (1914). The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás (Sixth, revised and corrected ed.). Allahabad, India: Ram Narain Lal Publisher and Bookseller. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- Indradevnarayan (1996) [1937]. कवितावली [Collection of Kavittas] (47th ed.). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. 108.

- Handoo, Chandra Kumari (1964). Tulasīdāsa: Poet, Saint and Philosopher of the Sixteenth Century. Bombay, Maharashtra, India: Orient Longmans. ASIN B001B3IYU8.

- Lamb, Ramdas (July 2002). Rapt in the Name: The Ramnamis, Ramnam, and Untouchable Religion in Central India. Albany, New York, United States of America: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791453858.

- Lutgendorf, Philip (23 July 1991). The Life of a Text: Performing the 'Ramcaritmanas' of Tulsidas. Berkeley, California, United States of America: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520066908.

- Lutgendorf, Philip (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey (Illustrated ed.). New York City, United States of America: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309218.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lyall, Charles James (1911). "Tulsī Dās". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 369–370.

- Macfie, J. M. (23 May 2004). The Ramayan of Tulsidas or the Bible of Northern India. Whitefish, Montana, United States of America: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 9781417914982. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- Mishra, Jwalaprasad (September 2010) [1858]. श्रीगोस्वामितुलसीदासजीकृत रामायण: विद्यावारिधि पं० ज्वालाप्रसादजीमिश्रकृत संजीवनीटीकासहित [The Ramayana composed by Goswami Tulsidas: With the Sanjivani commentary composed by Vidyavaridhi Pandit Jwalaprasad Mishra] (in Hindi). Mumbai, India: Khemraj Shrikrishnadass.

- Pandey, Ram Ganesh (2008) [2003]. तुलसी जन्म भूमि: शोध समीक्षा [The Birthplace of Tulasidasa: Investigative Research] (in Hindi) (Corrected and extended ed.). Chitrakuta, Uttar Pradesh, India: Bharati Bhavan Publication.

- Poddar, Hanuman Prasad (1996) [1940]. दोहावली [Collection of Dohas] (in Hindi) (37th ed.). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. 107.

- Poddar, Hanuman Prasad (1997) [1921]. विनयपत्रिका [Petition of Humility] (in Hindi) (47th ed.). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. 105.

- Prasad, Ram Chandra (2008) [1988]. Tulasidasa's Shri Ramacharitamanasa: The Holy Lake Of The Acts Of Rama (Illustrated, reprint ed.). Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804432.

- Publisher, Gita Press (2004). Śrīrāmacaritamānasa or The Mānasa lake brimming over with the exploits of Śrī Rāma (with Hindi text and English translation). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. ISBN 8129301466.

- Publisher, Gita Press (2007). श्रीरामचरितमानस मूल गुटका (विशिष्ट संस्करण) [Śrīrāmacaritamānasa Original Booklet (Special Edition)] (in Hindi) (9th ed.). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. ISBN 978-8129310903. 1544.

- Ralhan, O. P. (1997). The great gurus of the Sikhs, Volume 1. New Delhi, India: Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9788174884794.

- Rambhadracharya, Swami (7 April 2008). श्रीरामचरितमानस – भावार्थबोधिनी हिन्दी टीका (तुलसीपीठ संस्करण) [Śrīrāmacaritamānasa – The Bhāvārthabodhinī Hindi commentary (Tulasīpīṭha edition)] (PDF) (in Hindi) (3rd ed.). Chitrakuta, Uttar Pradesh, India: Jagadguru Rambhadracharya Handicapped University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Shukla, Usha Devi (2002). "Gosvāmī Tulasīdāsa and the Rāmacaritamānasa". Rāmacaritamānasa in South Africa. New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120818934.

- Singh, Uday Bhanu (2005). तुलसी [Tulsidas] (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9788171197361.

- Singh, Uday Bhanu (2008). तुलसी काव्य मीमांसा [Investigation into the poetry of Tulsidas] (in Hindi). New Delhi, India: Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9788171196869.

- Tripathi, Shiva Kumar (2004). "Who and What was Tulsidas?". A Garden of Deeds: Ramacharitmanas, a Message of Human Ethics. Bloomington, Indiana, United States of America: iUniverse. ISBN 9780595307920.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Tulsidas at the Internet Archive

- The Ramcharitmanas of Tulasidas, published by Gita Press

- Tulsidas Biography

- Indian male poets

- Hindi-language poets

- Hindu poets

- Epic poets

- Sant Mat

- 1511 births

- 1623 deaths

- Hindu revivalists

- Translators of the Ramayana

- Indian Hindu saints

- Scholars from Varanasi

- 16th-century Hindu religious leaders

- 16th-century Indian philosophers

- 16th-century Indian poets

- 16th-century Indian scholars

- Bhakti movement

- Poets from Uttar Pradesh

- Writers from Varanasi

- Vaishnava saints

- Longevity claims

- Miracle workers

- Awadhi writers