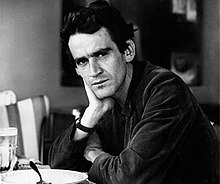

Gonzalo Arango

Gonzalo Arango Arias | |

|---|---|

Archivo de El Tiempo | |

| Born | January 18, 1931 Andes, Colombia |

| Died | September 25, 1976 (aged 45) Gachancipá, Colombia |

Gonzalo Arango Arias (Andes, Antioquia, 1931 – Gachancipá, Cundinamarca, 1976) was a Colombian writer, poet, and journalist. In 1958 he led a modern literary and cultural movement known as Nadaism (Nothing-ism),[1][2] inspired by surrealism, French existentialism, beat generation, dadaism, and influenced by the Colombian writer and philosopher Fernando González Ochoa.

Arango's life was characterized by large contrasts and contradictions, from an open atheism to an intense spirituality.[3] Those contrasts can be observed between the Primer manifiesto nadaísta (1958), or Prosas para leer en la silla eléctrica (1965), and his last writings.[4]

He was a strong critic of the society of his time and in his works he left many important ideas and proposals.[5]

He was planning to move to London with the British Angela Mary Hickie, but ended his life in a car accident in 1976.[6]

Life

[edit]Gonzalo Arango was born in Andes, a town of the Antioquian South-Eastern region in 1931, in a period known in Colombia as the liberal government that had to face the Great Depression. It was also the time of Constitutional and social reforms such as those intended by president Alfonso López Pumarejo. When he was an adolescent he saw the falling of the country into a bloody fight between the two traditional political parties, after El Bogotazo of April 9, 1948, a period of violent civil wars that was triggered by the murder of the presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. The Catholic Church in Colombia possessed the control of education, following the Colombian Constitution of 1886, and exerted a great authority over political, cultural and social matters, such as in the censorship of all intellectual material produced in the nation. One of the works by philosopher Fernando González Ochoa, "Viaje a pie" was forbidden by the Archbishop of Medellín, in 1929, under death penalty. This social and political context promoted his growing as a thinker and writer, and would influence Arango's work.

Arango was the last son of the 13 children of Francisco Arango (known as Don Paco) and Magdalena Arias. Don Paco was the telegraphist of the town, and his mother was a housewife.

His beginning as a writer

[edit]In 1947 he began to study Law in the University of Antioquia, but three years later he left the studies to devote himself to writing, starting with his first work "Después del hombre" (After the Man). About this time the poet Eduardo Escobar wrote:

(...) don Paco Arango, his father, went to visit him, concerned. He utterly disliked what he saw: the young poet thin and yellow, the pile of acid bones bitterly hairless, giving himself to write a novel. The title said everything. Its name was After the Man.[7]

The work: miscellany of genres

[edit]Gonzalo Arango ventures into different genres: autobiography, prose of ideas, literary criticism, comments, essays, prologues, letters, journalism, poetry, diverse narrative works, theater, chronicles, profiles, memories, notes, and reports. In Felipe Restrepo David words, -a studious of his work-, Arango stands out for a literature of ideas, for a narrative thought. His legacy is an essential work, "made of metaphors and thoughts," and "reflexive force and poetry."[8]

Gustavo Rojas Pinilla

[edit]On June 13, 1953, General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla led a bloodless Coup d'etat to the authoritarian conservative president Laureano Gómez intending to bring peace to the country, after many years of civil war between liberals and conservatives. The Assembly that replaced the Congress, composed mostly of conservatives, re-elected him for the next presidential period until 1958. The Rojas coup was seen by many as a possible solution to the political crisis, the violence in the country, and as an alternative to the extense monopole of the two traditional national parties. Young Arango was in those days a Rojas supporter, joining the Movimiento Amplio Nacional - MAN (National Wide Movement), composed of artists, writers, and young intellectuals.[7]

In this period, Arango devoted himself to journalism and literature.

Soon, however, the reaction of conservative and liberal leaders against Rojas Pinilla was manifested in an agreement that caused his fall on May 10, 1957. While the dictator was exiled in Spain, Gonzalo Arango fled to Chocó.

Creation of Nadaísmo

[edit]After his trip to Chocó he took refuge in the city of Cali, with a very poor and limited lifestyle, - as he writes in many letters to Alberto Aguirre. He started in 1957 to give form to the Nadaism ideas, that were expressed in the Primer Manifiesto nadaísta, published in Medellín in 1958. At the same time,he questioned himself deeply:

What do I have. He asked himself. Nothing. Nothing-ism (Nadaísmo). He tried to enlight the future upon the ruins, and decided to rise as a rebel against the horrible dullness.[9]

The first writers to join the new movement were Alberto Escobar, Guillermo Trujillo and Amílcar Osorio, and as an inauguration they burned, in 1958, in Plazuela de San Ignacio of Medellín, some of the official Colombian literature, as a symbol against what they considered the traditional masterpieces of a poor and official Colombian literature. And one of the books included was Arango's own first work, "After the Man".

The following year the Nadaists sabotaged the First Congress of Catholic Intellectuals in Medellín, and Arango was imprisoned in the same city. There he received Alberto Aguirre's help as a lawyer and friend, and the visit of Fernando González Ochoa, the philosopher of Otraparte, and one of his first admirators.

In 1963 he published a poetic anthology of thirteen Nadaists and wrote different articles for La Nueva Prensa and other journals.

Nadaísmo (Nothing-ism)

[edit]The Nadaísmo movement continues to be a matter of study and big interest, as it was an authentic literary and cultural revolution in Colombia.[10] A bohemian, intellectual and artistic movement with important proposals. Nadaísmo was Gonzalo Arango's creation and inspiration, and his goal was "not leaving intact any faith or any idol in place," according to the Primer Manifiesto nadaísta. The Movement was deeply entrenched in the 1960s and attracted young talented writers, painters, and artists of the time who created a strong mouvement in Colombia, with new poetry, novels, short stories, theatre, painting, drawing, publicity and journalism.

Nadaists manifested its inconformity against the social order of the time, under the rule of the two Colombian traditional political parties: Liberal and Conservative; his antagonism with a very rigid and conservative social structure; against the bourgeois ways of thinking and living; and opposed to revolutions with totalitarian aims.

It was thought by its own founder as ended, at the beginning of the 1970s, but was vigorously continued by other nadaist writers, as the poet Eduardo Escobar, even until modern times.[7]

The poet who wrote manifests and diatribes against Catholic writers, ended in a profound spirituality.[11] However, the movement is still alive in the interest, reading and writing of many youngsters, and with the editions and readings of their works by Corporación Otraparte and Eafit University.[12]

Gonzalo Arango was also a journalist and he participated in different newspapers and magazines within his country: El Tiempo, El Espectador, El Siglo, Nueva Prensa, Cromos Magazine, and Corno Emplumado (México) and Zona Franca (Venezuela). He published also the Nadaism magazine and the anthology of 13 Nadaist poets.

Works

[edit]- (1958) Primer manifiesto nadaísta (Manifiesto)

- (1959) Los camisas rojas (Manifiesto)

- (1959) Primer manifiesto vallecaucano (Manifiesto)

- (1960) Mensaje bisiesto a los intelectuales colombianos (Manifiesto)

- (1960) Exposición radiantiva de la poesía nadaísta (Manifiesto)

- (1960) Nada bajo el cielo raso (Teatro)

- (1960) HK-111 (Teatro)

- (1961) El manifiesto de los escribanos católicos (Manifiesto)

- (1962) El mensaje a los académicos de la lengua (Manifiesto)

- (1962) Sonata metafísica para que bailen los muertos (poesía)

- (1963) Sexo y saxofón (Cuento. Reflexiones de intimidad, prosa y poesía)

- (1963) Las promesas de Prometeo (Manifiesto)

- (1963) 13 poetas nadaístas (Antología poética)

- (1963) De la nada al nadaísmo (Antología poética)

- (1964) Los ratones van al infierno (Teatro)

- (1964) Consagración de la nada (Teatro)

- (1964) Medellín a solas contigo. (Prosa poética).

- (1966) Prosas para leer en la silla eléctrica. (Prosa, ficción, memorias, cuento, historias).

- (1967) El terrible 13 manifiesto nadaísta (Manifiesto)

- (1968) El oso y el colibrí. (Prosa de ideas.Incluye correspondencia con Evtushenko, crítica literaria, notas, semblanzas.).

- (1967) Boom contra Pum Pum (una revisión de Gabriel García Márquez)

- (1972) Providencia (Prosa y poesía)

- (1974) Fuego en el altar (Prosa y poesía)

- (1974) Obra Negra (cartas, diatribas, reflexiones, poesía)

- (1980) Correspondencia violada ( Memorias y cartas)

- (1985) Adangelios

- (1991) Memorias de un presidiario nadaísta (Memorias, autobiografía y reflexiones)

- (1993) Reportajes

- (2006) Cartas a Aguirre 1953-1965

- (2015) Cartas a Julieta

References

[edit]- ^ Pensamiento Colombiano Del Siglo XX, Volume 2, Page 199

- ^ National Geographic Traveler: Colombia - Page 51 Christopher Baker - 2012

- ^ Jaramillo, Maria Dolores. "Lo ético del nadaísmo".

- ^ Escobar, Eduardo (2023). Memorias sobre los vaivenes ideológicos de Gonzalo Arango al lado de su última novia, la inglesa. Angela Hickie (Historia de un cuadro ed.). Medellín: Universocentro.

- ^ Arango, Gonzalo, Primer manifiesto nadaista, 1958, gonzaloarango.com. Link retrieved on June 10, 2008.

- ^ Vélez Escobar, Juan Carlos, Hace 25 años se mató Gonzalo Arango, en gonzaloarango.com.

- ^ a b c Escobar, Eduardo (1989). "Boceto biográfico". Gonzalo Arango. Bogotá: Procultura, Colección Clásicos Colombianos. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ Jaramillo, María Dolores. "Gonzalo Arango: principios estéticos del nadaísmo".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Eduardo Escobar. "Nadaísmo revisado". gonzaloarango.com. Bogotá. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008.

Qué tenía. Se preguntó. Nada. Nadaísmo. Alumbró el futuro sobre la ruina. Decidió que se levantaría en rebeldía contra la horrible lascitud.

- ^ Jaramillo, Maria Dolores. "Los aportes del nadaísmo".

- ^ Eduardo Escobar (December 11, 2006). "Nadaísmo revisado". gonzaloarango.com. Bogota. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

Para Angelita, el nadaísmo murió en los años 70, enterrado por su propio progenitor. Y por eso recuerda que en Correspondencia violada Arango arremete contra sus discípulos y dice que están "desenterrando sus viejos cadáveres literarios para vivir de ellos en un sentido publicitario, maquillando su pasado de modernidad sin alma, huevos filosofales de plástico. ¡Qué falta de fe en la vida seguir creyendo que el nadaísmo es la salvación...!

- ^ Eduardo Escobar (December 11, 2006). "Nadaísmo revisado". gonzaloarango.com. Bogotá. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

External links

[edit]- Gonzalo Arango

- Gonzalo Arango biography at banrep.gov.co

- Escobar, Eduardo. Correspondencia violada. Bogotá: Instituto colombiano de cultura, 1989.

- Escobar, Eduardo. Gonzalo Arango. Bogotá: Procultura, 1980.

- Escobar, Eduardo. Nadaísmo crónico y demás epidemias. Bogotá: Arango Editores, 1991.