Adansonia digitata

| African baobab | |

|---|---|

| |

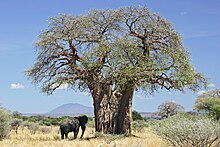

| Mature, flowering tree in Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Genus: | Adansonia |

| Species: | A. digitata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Adansonia digitata | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Adansonia digitata, the African baobab, is the most widespread tree species of the genus Adansonia, the baobabs, and is native to the African continent and the southern Arabian Peninsula (Yemen, Oman). These are long-lived pachycauls; radiocarbon dating has shown some individuals to be over 2,000 years old. They are typically found in dry, hot savannas of sub-Saharan Africa, where they dominate the landscape and reveal the presence of a watercourse from afar. They have traditionally been valued as sources of food, water, health remedies or places of shelter and are a key food source for many animals. They are steeped in legend and superstition. In recent years, many of the largest, oldest trees have died, for unknown reasons. Common names for the baobab include monkey-bread tree, upside-down tree, and cream of tartar tree.

Description

[edit]African baobabs are trees that often grow as solitary individuals, and are large and distinctive elements of savanna or scrubland vegetation. They grow to a height of 5–25 metres (16–82 feet).[2] The trunk is typically very broad and fluted or cylindrical, often with a buttressed, spreading base.[3] Trunks may reach a diameter of 10–14 m (33–46 ft),[3] and may be made up of multiple stems fused around a hollow core.[4] The hollow core found in many tree species is the result of wood removal, such as decay of the oldest, internal part of the trunk. In baobabs, however, many of the largest and oldest of the trees have a hollow core that is the result of a fused circle of three to eight stems sprouting from roots.[4] The bark is gray and usually smooth. The main branches can be massive. All baobabs are deciduous, losing their leaves in the dry season, and remaining leafless for about eight months of the year. Flowers are large, white and hanging. Fruits are rounded with a thick shell.[3]

The leaves are palmately compound with five to seven (sometimes up to nine) leaflets in mature trees, but seedlings and regenerating shoots may have simple leaves. The transition to compound leaves comes with age and may be gradual. African baobabs produce simple leaves much longer than most other Adansonia species. Leaflets are stalkless (sessile) to short-stalked and size is variable.[3]

Flowering occurs in both the dry and the wet season.[3] Buds are rounded with a cone-shaped tip. Flowers are showy and sometimes paired, but usually produced singly at the end of a hanging stalk about 15–90 centimetres (6–35+1⁄2 inches) in length. The calyx is typically made up of five (sometimes three) green triangular bent-back lobes (sepals) with a cream-coloured, hairy interior. The petals are white, roughly the same width and length – up to 8 cm (3 in), and are crumpled in bud.[3] Flowers open during the late afternoon, staying open and fertile for only one night.[5] The fresh flowers have a sweet scent, but after about 24 hours, they start to turn brown and emit a carrion smell.[5] The androecium is white and made up of a 3–6 cm (1+1⁄4–2+1⁄4 in) long tube of fused stamens (a staminal tube) surrounded by unfused (free) filaments 3–5 cm long. There are a large number of stamens, 720–1,600 per flower, with reports of up to 2,000.[6] Styles are white, growing through the staminal tube and projecting beyond it. They are usually bent at right-angles and topped with an irregular stigma. Pollen grains are spherical with spikes over the surface, typical of the Malvaceae family. Pollen grain diameter is around 50 microns.[7]

All Adansonia develop large rounded indehiscent fruits which can be up to 25 cm (10 in) long with a woody outer shell. African baobab fruits are quite variable in shape, from nearly round to cylindrical. The shell is 6–10 millimetres (1⁄4–3⁄8 in) thick.[3] Inside is a fleshy, light beige coloured pulp. As it dries, the pulp hardens into a crumbly powder.[8] The seeds are hard and kidney-shaped with a .06-mm-thick coat.[8] They show long-term dormancy, only germinating after fire or passing through an animal's digestive tract.[8] It is thought that this is because the seed coat needs to be cracked or thinned to allow to water to penetrate before the seed can germinate.[8]

-

Each leaf comprises five leaflets

-

Open flower

-

Bisected flower

-

Two pollen grains overlapped

-

Fruit

-

Hanging fruits at Ala Moana Beach Park, Oahu in Hawaii

-

Seeds with coins

Water storage

[edit]Baobab trees store water in their trunks and branches on a seasonal basis as they live in areas of sustained drought and water inaccessibility. The spongy material of the bark allows water to be absorbed deeper into the tissue, as there is rarely enough rain during the wet season to penetrate the litter layer of soil.[9] The U-shaped branches allow for water to trickle down, allowing for maximum absorption over an extended period of time even after the rain stops.[10] The water is absorbed into the vascular tissue of the tree, where it can be moved into the tree's parenchyma cells for long-term storage, or used.[11] A large Baobab can store as much as 136,400 liters of water.[12]

During the dry season, the trees will flush out all of their leaves.[9] During this period, the circumference of the trunk will shrink about 2–3 cm and the water content of the stem will drop by about 10%.[13] Dropping leaves during the dry season is done to prevent water loss through transpiration out of the stomata, which would cause the water potentials in the vascular tissue to drop too low and pull water out of the vacuoles in the parenchyma cells. This would lead to the parenchyma cells, which make up the majority of the trunk and branches, to plasmolyze destroying the tree.[9]

The water in storage cells is structurally important, which limits their ability to use mass quantities of stored water in times of drought. Baobab trees have much higher water and parenchyma content than most trees, this allows them to grow very large with less energy expenditure.[14] Parenchyma are soft plant tissue cells that are commonly used for water storage in other drought tolerant species like cactus and succulents. The water fluxes from the vascular tissue into the parenchyma cells at the center of the tree with the help of actively transported ions. The ion flux into the cell will shift the concentration gradients, causing water to rush into the cells for long-term storage.[citation needed]

Another reason why the water in the trunk can only be used as a buffer for long-term deficits is the distance between the vascular tissue and the parenchyma. The transportation of water from the vascular tissue into storage cells is a very slow process as it is a high-resistance path.[13] The water in the cells at the core of the trunk and the branches would take too much energy from the tree to move back into the vascular tissue for daily use.[citation needed]

Longevity

[edit]The growth rate of baobab trees is determined by ground water or rainfall.[5][15] The trees produce faint growth rings, but counting growth rings is not a reliable way to age baobabs because some years a tree will form multiple rings and some years none.[16]

Radiocarbon dating has provided data on a few individual A. digitata specimens. The Panke baobab in Zimbabwe was some 2,450 years old when it died in 2011, making it the oldest angiosperm ever documented, and two other trees—Dorslandboom in Namibia and Glencoe in South Africa—were estimated to be approximately 2,000 years old.[17] Another specimen known as Grootboom was dated after it died and found to be at least 1,275 years old.[18][19] Baobabs may be so long-lived in part due to their ability to periodically sprout new stems.[4]

Taxonomy

[edit]The scientific name Adansonia refers to the French explorer and botanist, Michel Adanson (1727–1806), who wrote the first botanical description for the full species.[3] "Digitata" refers to the digits of the hand, as the baobab has compound leaves with normally five (but up to seven) leaflets, akin to a hand.[20] A. digitata is the type species for the genus Adansonia and is the only species in the section Adansonia.[3] All species of Adansonia except A. digitata are diploid; A. digitata is tetraploid.[21] Some populations of African baobab have significant genetic differences and it has been suggested that the taxon contains more than one species. For example, the shape of the fruit varies considerably from region to region.[22] In Angola, the fruits are elongated, rather than round.[3] A proposed new species (Adansonia kilima Pettigrew, et al.), was described in 2012, found in high-elevation sites in eastern and southern Africa.[21] This is now however no longer recognized as a distinct species[7] but considered a synonym of A. digitata. Some high-elevation trees in Tanzania show different genetics and morphology but further study is needed to determine if they should be considered a separate species.[7]

History

[edit]The earliest written reports of African baobab are from a 14th-century travelogue by the Arab traveler Ibn Batuta.[3] The first botanical description was by Alpino (1592) looking at fruits that he observed in Egypt from an unknown source. They were called Bahobab, possibly from the Arabic "bu hibab", meaning "many-seeded fruit".[3] The French explorer and botanist, Michel Adanson observed a baobab tree in 1749 on the island of Sor, Senegal and wrote the first detailed botanical description of the full tree, accompanied with illustrations. Recognizing the connection to the fruit described by Alpino he called the genus Baobab. Linnaeus later renamed the genus Adansonia, to honour Adason, but use of baobab as one of the common names has persisted.[3] Additional common names include monkey-bread tree (the soft, dry fruit is edible), upside-down tree (the sparse branches resemble roots), and cream of tartar tree (cream of tartar) because of the powdery fruit pulp.[23]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The African Baobab is associated with tropical savannas.[8] It is found in drier climates, is sensitive to water logging and frost and is not found in areas where sand is deep.[24] It is native to mainland Africa, between the latitudes 16° N and 26° S.[4] Some references consider it as introduced to Yemen and Oman[25] while others consider it native there.[19] The tree has also been introduced to many other regions including Australia and Asia.[26]

The northern limit of its distribution in Africa is associated with rainfall patterns; only on the Atlantic coast and in the Sudanian savanna does its occurrence venture naturally into the Sahel. On the Atlantic coast, this may be due to spreading after cultivation. Its occurrence is very limited in Central Africa, and it is found only in the very north of South Africa. In East Africa, the trees grow also in shrublands and on the coast. In Angola and Namibia, the baobabs grow in woodlands, and in coastal regions, in addition to savannas.[27] The African Baobab is native to Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Niger, Nigeria, northern Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, Congo Republic, DR Congo (formerly Zaire), Eritrea, Ethiopia, southern Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, Angola, São Tomé, Príncipe, Annobon, South Africa (in Limpopo province, north of the Soutpansberg mountain range), Namibia, Botswana.[25][24] It is an introduced species in Java, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Seychelles, Comoros, India, Guangdong, Fujian, Yunnan[25] and has been planted in Penang, Malaysia, along certain streets.[28] Arab traders introduced it to northwestern Madagascar where baobab trees were often planted at the center of villages.[2]

Ecology

[edit]All baobabs are deciduous, losing their leaves in the dry season, and remaining leafless for about eight months of the year.[3] The African baobab is largely found in savannah habitats, which tend to be fire-prone. Adaptations to survive frequent fires include a thick and fire-resistant bark and thick-shelled fruit. Trees older than about 15 years have thick enough bark to withstand the heat of most savannah fires, while younger trees can resprout after fire.[8] The thick outer shell of the fruit may serve to protect the seeds.

Pollination in the African baobab is achieved primarily by fruit bats, in West Africa mainly the straw-coloured fruit bat, Gambian epauletted fruit bat, and the Egyptian fruit bat. The flowers are also visited by galagos, and several kinds of insect.[29]

With their hard coat, baobab seeds can withstand drying and remain viable over long periods. The fruits are eaten by many species and the germination potential is improved when seeds have passed through the digestive tract of an animal or have been subjected to fire.[3] Elephants and baboons are main dispersal agents[3] and so the seeds can potentially be dispersed over long distances. The fruits float and the seeds are waterproof, so African baobabs may also be spread by water.[3] Some aspects of the baobab's reproductive biology are not yet understood but it is thought that pollen from another tree may be required to develop fertile seed. Isolated trees without a pollen source from another tree do form fruit, only to abort them at a later stage. The existence of some very isolated trees may then be due to their ability to disperse long distances but self-incompatibility.[22]

The fruit, bark, roots and leaves are a key food source for many animals and the trees themselves are an important source of shade and shelter.[30]

Conservation

[edit]The baobab is a protected tree in South Africa,[31] and yet is threatened by various mining and development activities.[32] In the Sahel, the effects of drought, desertification and over-use of the fruit have been cited as causes for concern.[33] As of March 2022 African baobab is not yet classified by the IUCN Red List, although there is evidence that populations may be declining. Many of the largest and oldest African baobabs have died in recent years.[30] Greenhouse gases, climate change, and global warming appear to be factors reducing baobab longevity.[34]

Uses

[edit]

People have traditionally valued the trees as sources of food, water, health remedies or places of shelter. The baobab is a traditional food plant in Africa, but is little-known elsewhere.[5] Adanson concluded that the baobab, of all the trees he studied, "is probably the most useful tree in all." He consumed baobab juice twice a day while in Africa, and was convinced that it maintained his health.[35] According to a modern field guide, the juice can help cure diarrhoea.[36]

The roots and fruits are edible.[36] The fruit has been suggested to have the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development and support sustainable land care.[37] In Sudan – where the tree is called tebeldi تبلدي – people make tabaldi juice by soaking and dissolving the dry pulp of the fruit in water, locally known as gunguleiz.[38] Water can also be extracted from some of the trunks.[36]

Baobab leaves can be eaten as a relish. Young fresh leaves are cooked in a sauce and sometimes are dried and powdered. The powder is called lalo in Mali and sold in many village markets in Western Africa. The leaves are used in the preparation of a soup termed miyan kuka in Northern Nigeria and are rich in phytochemicals and minerals.[39] The seeds can be pounded into a flour[36] or to extract oil for cooking.[40] Baobab leaves are sometimes used as forage for ruminants in dry season. The oilmeal, which is a byproduct of oil extraction, can also be used as animal feed.[41] Whole fruits or just the fruit pulp can be stored for months under dry conditions. [42]

The fiber of the bark can be used to make cloth.[43] In times of drought, elephants consume the juicy wood beneath the bark of the baobab.[43]

For export

[edit]In 2008, the European Union approved the use and consumption of baobab fruit. It is commonly used as an ingredient in smoothies and cereal bars.[44] In 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration granted generally recognized as safe status to baobab dried fruit pulp as a food ingredient.[45]

In culture

[edit]Along the Zambezi, the tribes believed that baobabs were upright and too proud. The gods became angry and uprooted them and threw them back into the ground upside-down. Evil spirits now cause bad luck to anyone that picks up the sweet white flowers. More specifically, a lion will kill them.[46] In Kafue National Park, one of the largest baobabs is known as "Kondanamwali" or the "tree that eats maidens". The tree fell in love with four beautiful maidens. When they reached puberty, they made the tree jealous by finding husbands. So, one night, during a thunderstorm, the tree opened its trunk and took the maidens inside. A rest house has been built in the branches of the tree. On stormy nights, the crying of the imprisoned maidens can still be heard.[46]

Some people believe that women living in kraals where baobabs are plenty will have more children. This is scientifically plausible as those women will have better access to the tree's vitamin-rich leaves and fruits to complement a vitamin-deficient diet.[46]

The tree also plays a role in Antoine De Saint-Exupéry's fictional children's book, The Little Prince. In the story, baobabs are described as dangerous plants which must be weeded out from the good plants, lest they overcome a small planet and even break it to pieces.[47]

Prominent specimens

[edit]A number of individual baobab trees attract sightseers due to their age, size, history, location or isolated occurrence.

Botswana

[edit]Around Gweta, Botswana, some have been declared national monuments. Green's Baobab, 27 km south of Gweta was inscribed by the 19th-century hunters and traders Frederick Thomas Green and Hendrik Matthys van Zyl besides other ruthless characters. Fred and Charles Green passed the baobab during an expedition to Lake Ngami and left the inscription "Green's Expedition 1858–1859". An earlier inscription by an unknown traveller reads "1771".[48] About 11 km south of Green's Baobab is the turn-off to Chapman's Baobab, also known as Seven Sisters or Xaugam, i.e. "lion's tail" in Tsoa. It was once an enormous multi-stemmed tree, used by passing explorers, traders and travellers as a navigation beacon. It guided them as they navigated the extensive salt pan northwards, while a hollow in the trunk served as a letterbox. The explorer and hunter James Chapman left an engraving on a large root when he passed the tree with artist Thomas Baines in 1861, but Livingstone, Oswell, Moffat, and Selous also camped here. Livingstone supposedly carved a cross and his initials, and conveyed his 1853 sojourn in Missionary Travels, noting: "about two miles beyond [the immense saltpan Ntwetwe] we unyoked under a fine specimen of baobab, ... It consisted of 6 branches united into one trunk."[49] It had a circumference of 25 m before its constituent trunks collapsed outward on 7 January 2016. Not all its trunks are confirmed dead however,[citation needed] one showing signs of life in 2019.[50] Seven trees known as the Sleeping Sisters or Baines' Baobabs grow on a tiny islet in Kudiakam Pan, Botswana. They are named for Thomas Baines who painted them in May 1862, while en route to Victoria Falls. The fallen giant of Baines' day is still sprouting leaves (as of 2004), and a younger generation of trees are in evidence. The islet is accessible in winter when the pan is dry.[51] Some large specimens have been transplanted to new sites, as was the one at Cresta Mowana lodge in Kasane.[52]

Ghana

[edit]At Saakpuli (also Sakpele) in northern Ghana the site of a 19th-century slave transit camp is marked by a stand of large baobabs, to which slaves were chained.[53] The chains were wrapped around their trunks or around the roots. Similarly, two trees at Salaga in central Ghana are reminders of the slave trade. One, located at the former slave market at the center of town, was replanted at the site of the original to which slaves were shackled. A second larger tree marks the slave cemetery, where bodies of dead slaves were dumped.

India

[edit]Inside the Golconda Fort in Hyderabad, India, is a baobab tree estimated to be 430 years old. It is the largest baobab outside of Africa.[54]

Sri Lanka

[edit]It grows in Mannar peninsula and opposite mainland, Delft island, Wilpaththu and Puththam. Baobab has Tamil vernacular names – Perukku-Maran and Papparappuli. English Name 'Monkey bread. Sinhala name - Aliyagaha (Sri lanka wild life interlude vol l ) It is said that the tree in Pallimunai of Mannar island is the oldest and largest one of 800 years old. Local tradition is that this tree brought to SL by Arabs to feed their camels by its leaves.[citation needed]

Madagascar

[edit]

The African baobab in Mahajanga, Madagascar, had a circumference of 21 metres by 2013. It became the symbol of the city and was formerly a place for executions and important meetings.[55]

Mozambique

[edit]The Lebombo Eco Trail tree is about 18.5 m tall with a diameter of almost 22 m. It was found to be about 1400 years old and made up of five stems with ages between 900 and 1400 years, fused in a ring leaving a large central cavity.[4]

Namibia

[edit]The Ombalantu baobab in Namibia has a hollow trunk that can accommodate some 35 people. At times it has served as a chapel, post office, house, and hiding site. The Holboom baobab (Holboom, Nyae Nyae Conservancy, Namibia) is one of the trees with a hollow core. It measures 35.10 m around and radiocarbon dating shows it to be about 1750 years old.[4]

Republic of the Congo

[edit]The Arbre de Brazza is a baobab in the Republic of the Congo under which de Brazza and his companions Dolisie, Chavannes and Ballay made a stop in 1877, as their engraving "EB 1887" still attests. Another engraving, "Mâ Prince", was left by president Nguesso in his youth.[citation needed]

Senegal

[edit]The first botanical description of A. digitata was done by Adanson based on a tree on the island of Sor, Senegal. On the nearby Îles des Madeleines Adanson found a baobab that was 3.8 metres (12 ft) in diameter, which bore the carvings of passing mariners on its trunk, including those of Prince Henry the Navigator in 1444 and André Thevet in 1555.[2] When Théodore Monod searched the island in the 20th century, this tree was not to be found. The Gouye Ndiouly or Guy Njulli ("baobab of circumcision") may be the oldest baobab in Senegal and the northern hemisphere.[56] The partially collapsed tree from which new stems have emerged is situated near the bank of the Saloum River at Kahone. It was formerly the venue for the gàmmu, an annual festival during which the kingdom's provincial rulers pledged their loyalty to the king.[57] From 1593 to 1939, 49 kings of the Guélewars dynasty were inducted at this tree. It was beside the place where the Buur Saloum organized circumcision ceremonies,[56][58] and in 1862, it became the scene of a battle.

US Virgin Islands

[edit]

The Grove Place Baobab, listed as a Champion Tree, is believed to be the oldest (250–300 years) of some 100 baobabs on Saint Croix in the US Virgin Islands. It is seen as a living testament to centuries of African presence, as the seeds were likely introduced by an African slave who arrived at the former estate during the 18th century. According to the bronze memorial plaque, twelve women were rounded up during the 1878 Fireburn labor riot, and burned alive beneath the tree. It has since been a rallying place for plantation laborers and unions.[59]

Zimbabwe

[edit]Zimbabwe's Big Tree, near Victoria Falls, stands 25 meters tall and is visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists yearly. Radiocarbon dating has shown this one to be made up of several stems of various ages, with the oldest about 1150 years old.[16]

Additional images

[edit]-

Baobab at the slave cemetery, Salaga. The white calico cloth indicates its spiritual significance.

-

Without leaves in Tarangire National Park, Tanzania

-

Leaves

-

Elements of the fruit pulp (clockwise from top right): chunks, fibers, seeds, and pulp powder

References

[edit]- ^ "Adansonia digitata L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Wickens, G.E. (2008-03-02). The Baobabs: Pachycauls of Africa, Madagascar and Australia. Berlin] [New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-4020-6431-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Baum, David A. (1995). "A Systematic Revision of Adansonia (Bombacaceae)". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 82 (3). Missouri Botanical Garden Press: 440–471. doi:10.2307/2399893. ISSN 0026-6493. JSTOR 2399893.

- ^ a b c d e f Patrut, Adrian; Woodborne, Stephan; von Reden, Karl F.; Hall, Grant; Hofmeyr, Michele; Lowy, Daniel A.; Patrut, Roxana T. (2015-01-26). "African Baobabs with False Inner Cavities: The Radiocarbon Investigation of the Lebombo Eco Trail Baobab". PLOS ONE. 10 (1): e0117193. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1017193P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117193. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4306539. PMID 25621989.

- ^ a b c d Hankey, Andrew (February 2004). "Adansonia digitata A L." PlantZAfrica.com. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Jaeger, Paul (1961). The Wonderful Life of Flowers. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. p. 163.

- ^ a b c Cron, G.V.; Karimi, N.; Glennon, K.L.; Udeh, C.; Witkowski, E.T.F.; Venter, S.M.; Assogbadio, A.; Baum, D.A. (2016). "One African baobab species or two? A re-evaluation of Adansonia kilima". South African Journal of Botany. 103: 312. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2016.02.036.

- ^ a b c d e f Kempe, Andreas; Neinhuis, Christoph; Lautenschläger, Thea (2018). "Adansonia digitata and Adansonia gregorii fruit shells serve as a protection against high temperatures experienced during wildfires". Botanical Studies. 59 (1): 7. Bibcode:2018BotSt..59....7K. doi:10.1186/s40529-018-0223-0. ISSN 1999-3110. PMC 5816730. PMID 29455307.

- ^ a b c Chapotin, Saharah Moon; Razanameharizaka, Juvet H.; Holbrook, N. Michele (June 2006). "Water relations of baobab trees (Adansonia spp. L.) during the rainy season: does stem water buffer daily water deficits?". Plant, Cell and Environment. 29 (6): 1021–1032. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01456.x. ISSN 0140-7791. PMID 17080930.

- ^ "The Adaptations of the Baobab Tree". Sciencing. 13 March 2018. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ Chapotin, S. M.; Razanameharizaka, J. H.; Holbrook, N. M. (2006-09-01). "A biomechanical perspective on the role of large stem volume and high water content in baobab trees (Adansonia spp.; Bombacaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 93 (9): 1251–1264. doi:10.3732/ajb.93.9.1251. ISSN 0002-9122. PMID 21642189.

- ^ Palmer, Eve; Pitman, Norah (1972). Trees of South Africa-Volume 2. Cape Town: A.A. Balkema. p. 1459.

- ^ a b Chapotin, Saharah Moon; Razanameharizaka, Juvet H.; Holbrook, N. Michele (February 2006). "Baobab trees ( Adansonia ) in Madagascar use stored water to flush new leaves but not to support stomatal opening before the rainy season". New Phytologist. 169 (3): 549–559. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01618.x. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 16411957.

- ^ Van den Bilcke, N.; De Smedt, S.; Simbo, D. J.; Samson, R. (2013-09-01). "Sap flow and water use in African baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) seedlings in response to drought stress". South African Journal of Botany. 88: 438–446. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2013.09.006. ISSN 0254-6299.

- ^ Grové, Naas (November 2011). "Redaksionele Kommentaar" (PDF). Dendron (in Afrikaans) (43): 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ a b Kornei, Katherine (12 Nov 2021). "Scientists determine the age of one of Africa's most famous trees". Science. doi:10.1126/science.acx9629. S2CID 244097751.

- ^ Patrut, Adrian; Woodborne, Stephan; Patrut, Roxana T.; Rakosy, Laszlo; Lowy, Daniel A.; Hall, Grant; von Reden, Karl F. (2018-06-11). "The demise of the largest and oldest African baobabs". Nature Plants. 4 (7): 423–426. Bibcode:2018NatPl...4..423P. doi:10.1038/s41477-018-0170-5. hdl:2263/65292. ISSN 2055-0278. PMID 29892092. S2CID 47017569.

- ^ Patrut, Adrian; Mayne, Diana H; von Reden, Karl F; Lowy, Daniel A; Pelt, Robert van; McNichol, Ann P; Roberts, Mark L; Margineanu, Dragos (2010). "Fire History of a Giant African Baobab Evinced by Radiocarbon Dating". Radiocarbon. 52 (2). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 717–726. Bibcode:2010Radcb..52..717P. doi:10.1017/s0033822200045732. hdl:1912/4374. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ a b "Adansonia digitata (baobab)". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ^ du Plessis, Doep (November 2011). "Die Thabazimbi-bosveld se groot kremetart" (PDF). Dendron (in Afrikaans) (43): 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ a b Pettigrew, J. D.; et al. (2012). "Morphology, ploidy and molecular phylogenetics reveal a new diploid species from Africa in the baobab genus Adansonia (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae)" (PDF). Taxon. 61 (6): 1240–1250. doi:10.1002/tax.616006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ a b van Wyk, Braam (November 2011). "Kommentaar oor die groot kremetart van Gannahoek" (PDF). Dendron (in Afrikaans) (43): 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ "Monkey-bread tree (Adansonia digitata) | spotwild". spotwild.org. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ a b "Descriptions and articles about the Baobab (Adansonia digitata) - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "Catalogue of Life - Adansonia digitata L." catalogueoflife.org. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Curious Kimberley: Scientists disagree how boab trees got to Australia from Africa and Madagascar - ABC News". www.abc.net.au. August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Adansonia digitata:Plant Database of India". Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Gardner, Simon; Sitthisunthō̜n, Phindā; Lai, Ee May (2011). Heritage Trees of Penang. Penang: Areca books. ISBN 978-967-5719-06-6.

- ^ Baum, David A. (1995). "The Comparative Pollination and Floral Biology of Baobabs (Adansonia- Bombacaceae)". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 82 (2): 322–348. doi:10.2307/2399883. ISSN 0026-6493. JSTOR 2399883.

- ^ a b Pennisi, Elizabeth. "Africa's strangest trees are stranger than thought—and they're dying mysteriously". Science News. Science. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Protected Trees" (PDF). Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Republic of South Africa. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010.

- ^ Bega, Sheree (20 March 2021). "Plan to uproot 100 000 trees in Limpopo 'sacrilege', says baobab expert". Environment. mg.co.za. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Osman, Siham M. (2014). "Save the Baobab". practicalaction.org. ITDG Practical Action Sudan. Archived from the original on 2015-12-02. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Ed Yong (11 June 2018). "Trees That Have Lived for Millennia Are Suddenly Dying The oldest baobabs are collapsing, and there's only one likely explanation". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "The Baobab Tree". Powbab. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, United States Department of the Army. 2009. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364.

- ^ National Research Council (October 27, 2006). "Baobab". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables. Vol. 2. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/11763. ISBN 978-0-309-10333-6. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Gebauer, J. (2013). "A note on baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) in Kordofan, Sudan". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 60 (4): 1587–1596. doi:10.1007/s10722-013-9964-5. S2CID 6884609.

- ^ Ogbaga, Chukwuma; Nuruddeen, Fatima; Alonge, Olatunbosun; Nwagbara, Onyinye (November 2017). "Phytochemical, elemental and proximate analyses of stored, sun-dried and shade-dried baobab (Adansonia digitata) leaves". 2017 13th International Conference on Electronics, Computer and Computation (ICECCO). pp. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICECCO.2017.8333339. ISBN 978-1-5386-2499-9.

- ^ Sidibe, M.; Williams, J. T. (2002). Baobab - Adansonia digitata (PDF). Southampton, UK: International Centre for Underutilised Crops. pp. 43, 48. ISBN 978-0854327768. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-06. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- ^ Heuzé, V.; Tran, G.; Bastianelli, D.; Archimède, H. (January 25, 2013). "African baobab (Adansonia digitata)". Feedipedia.org. A programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ "a Review on a Multipurpose Tree with Promising Future in the Sudan" (PDF).

- ^ a b Sheehan, Sean (2004). Zimbabwe (Vol. 6 of Cultures of the World) (2nd ed.). New York: Benchmark Books/Marshall Cavendish. p. 13. ISBN 9780761417064.

- ^ "Baobab dried fruit pulp". Advisory Committee on Novel Foods and Processes. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03.

- ^ Laura M. Tarantino (July 25, 2009). "Agency Response Letter GRAS Notice No. GRN 000273". FDA.

- ^ a b c "Boabab Tree - Southern African Trees - Adansonia digitata". krugerpark.co.za. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry, Antoine (1943). Le Petit Prince [The Little Prince]. Reynal and Hitchcock.

- ^ "The Historic Baobabs in Botswana". discoverafrica.com. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Julie (2012). Looking for Mrs Livingstone. Saint Andrew Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780715209646.

- ^ le Breton, Gus (29 October 2019). "Is Chapman's Baobab Still Alive? Update from Botswana". African Plant Hunter. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Watson, Rupert (2007). The African baobab. Cape Town: Struik. pp. 190–191. ISBN 9781770074309.

- ^ Ashby, Alison (26 June 2013). "The baobab's secret". zambezitraveller.com. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2014). Ghana: the Bradt travel guide (6 ed.). Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 427. ISBN 9781841624785.

- ^ Syed Akbar (25 July 2018). "ASI conducts health check up of 430-year-old baobab tree of Golconda, says it's healthy". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ Sipa, Masika (2013). "The Old Baobab of Mahajanga". madamagazine.com. MadaMagazine. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ a b Pătruţ, prof. dr. Adrian (project manager) (2015). "New research in dendrochronology and environmental climate change by using AMS/CFAMS radiocarbon dating and stable isotope analysis". chem.ubbcluj.ro. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Ross, Eric (25 January 2012). "Historic baobab trees of Senegal: Kahone". ericrossacademic.wordpress.com. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "Kahone, Ancienne capitale du Saloum: Passé-présent d'une ville pluricentenaire". sinesaloum.info. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "New St. Croix Park Celebrates the Legacy of the Baobab Tree". Repeating Islands. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

External links

[edit]- Description and cultural information

- Structured description

- PROTAbase on Adansonia digitata

- Feedipedia on Adansonia digitata

- Adansonia digitata in Brunken, U., Schmidt, M., Dressler, S., Janssen, T., Thiombiano, A. & Zizka, G. 2008. West African plants - A Photo Guide. www.westafricanplants.senckenberg.de.

- Adansonia

- Flora of West Tropical Africa

- Flora of Northeast Tropical Africa

- Flora of South Tropical Africa

- Fruits originating in Africa

- Flora of Angola

- Flora of Botswana

- Flora of Cameroon

- Flora of Ethiopia

- Flora of Kenya

- Flora of Madagascar

- Flora of Namibia

- Flora of Tanzania

- Trees of Africa

- Protected trees of South Africa

- Plants described in 1753

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus