Saraswati

| Saraswati | |

|---|---|

Mother Goddess Goddess of knowledge, education, learning, speech, arts, music, poetry, purification, language and culture[1][2] Personification of the Sarasvati River | |

| Member of Tridevi and Pancha Prakriti | |

Painting of Sarasvati by Raja Ravi Varma | |

| Other names | |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Sarasvatī |

| Devanagari | सरस्वती |

| Affiliation | |

| Abode | |

| Mantra |

|

| Symbols |

|

| Day | Friday |

| Colour |

|

| Mount | |

| Festivals | Vasant Panchami, Sarasvati Puja and seventh day of Navaratri |

| Consort | Brahma |

Saraswati (Sanskrit: सरस्वती, IAST: Sarasvatī), also spelled as Sarasvati, is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism, revered as the goddess of knowledge, education, learning, arts, speech, poetry, music, purification, language and culture.[1][2] Together with the goddesses Lakshmi and Parvati, she forms the trinity, known as the Tridevi.[4][5][6] Sarasvati is a pan-Indian deity, venerated not only in Hinduism but also in Jainism and Buddhism.[7][6]

She is one of the prominent goddesses in the Vedic tradition (1500 to 500 BCE) who retains her significance in later Hinduism.[1] In the Vedas, her characteristics and attributes are closely connected with the Sarasvati River, making her one of the earliest examples of a river goddess in Indian tradition. As a deity associated with a river, Sarasvati is revered for her dual abilities to purify and to nurture fertility. In later Vedic literature, particularly the Brahmanas, Sarasvati is increasingly identified with the Vedic goddess of speech, Vac, and eventually, the two merge into the singular goddess known in later tradition. Over time, her connection to the river diminishes, while her association with speech, poetry, music, and culture becomes more prominent. In classical and medieval Hinduism, Sarasvati is primarily recognized as the goddess of learning, arts and poetic inspiration, and as the inventor of the Sanskrit language.[2][1] She is linked to the creator god Brahma, either as his consort or creation. In this role, she represents his creative power (Shakti), giving reality a unique and distinctly human quality. She becomes linked with the dimension of reality characterized by clarity and intellectual order.[1] Within the goddess oriented Shaktism tradition, Sarasvati is a key figure and venerated as the creative aspect of the Supreme Goddess.[8][9] She is also significant in certain Vaishnava traditions, where she serves as one of Vishnu's consorts and assists him in his divine functions.[10][1] Despite her associations with these male deities, Sarasvati equally stands apart as an independent goddess in the pantheon, worshipped without a consort.[11]

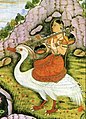

She is portrayed as a serene woman with a radiant white complexion, dressed in white attire, representing the quality of sattva (goodness). She has four arms, each holding a symbolic object: a book, a rosary, a water pot, and a musical instrument known as the veena. Beside her is her mount, either a hamsa (white goose or swan) or a peacock.[1] Hindu temples dedicated to Sarasvati can be found worldwide, with one of the earliest known shrines being Sharada Peeth (6th–12th centuries CE) in Kashmir.[12] Sarasvati continues to be widely worshipped across India, particularly on her designated festival day, Vasant Panchami (the fifth day of spring, and also known as Sarasvati Puja and Sarasvati Jayanti in many regions of India), when students honor her as the patron goddess of knowledge and education.[1][13] Traditionally, the day is marked by helping young children learn how to write the letters of the alphabet.[14]

In Buddhism, she is venerated in many forms, including the East Asian Benzaiten (辯才天, "Eloquence Talent Deity").[15][16] In Jainism, Sarasvati is revered as the deity responsible for the dissemination of the Tirthankaras' teachings and sermons.[17]

Etymology

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Sarasvati is a Sanskrit fusion word of saras (सरस्) meaning "pooling water", but also sometimes translated as "speech"; and vati (वती), meaning "she who possesses". Originally associated with the river or rivers known as Sarasvati, this combination, therefore, means "she who has ponds, lakes, and pooling water" or occasionally "she who possesses speech". It is also a Sanskrit composite word of sarasu-ati (सरसु+अति) which means "one with plenty of water".[18][19]

The word Sarasvati appears both as a reference to a river and as a significant deity in the Rigveda. In initial passages, the word refers to the Sarasvati River and is mentioned as one among several northwestern Indian rivers such as the Drishadvati. Sarasvati, then, connotes a river deity. In Book 2, the Rigveda describes Sarasvati as the best of mothers, of rivers, of goddesses.[19]

Her importance grows in the later Vedas composed after the Rigveda as well as in the later Brahmana texts, and the word evolves in its meaning from "waters that purify", to "that which purifies", to "vach (speech) that purifies", to "knowledge that purifies", and ultimately into a spiritual concept of a goddess that embodies knowledge, arts, music, melody, muse, language, rhetoric, eloquence, creative work and anything whose flow purifies the essence and self of a person.[19][20]

Names and epithets

Sarasvati (Sanskrit: Sarasvatī) is known by many names. Some examples of synonyms for Sarasvati include Sharada (bestower of essence or knowledge),[1] Brahmani (power of Brahma), Brahmi (goddess of sciences),[21] Bharadi (goddess of history), Vani and Vachi (both referring to the flow of music/song, melodious speech, eloquent speaking respectively), Varnesvari (goddess of letters), Kavijihvagravasini (one who dwells on the tongue of poets).[22][1]

Other names include: Ambika, Bharati, Chandrika, Devi, Gomati, Hamsasana, Saudamini, Shvetambara, Subhadra, Vaishnavi, Vasudha, Vidya, Vidyarupa, and Vindhyavasini.[23]

In the Tiruvalluva Maalai, a collection of fifty-five Tamil verses praising the Kural literature and its author Valluvar, she is referred to as Nāmagal and is believed to have composed the second verse.[24][25]

Outside Nepal and India, she is known in Burmese as Thurathadi (သူရဿတီ, pronounced [θùja̰ðədì] or [θùɹa̰ðədì]) or Tipitaka Medaw (တိပိဋကမယ်တော်, pronounced [tḭpḭtəka̰ mɛ̀dɔ̀]), in Chinese as Biàncáitiān (辯才天), in Japanese as Benzaiten (弁才天/弁財天) and in Thai as Suratsawadi (สุรัสวดี) or Saratsawadi (สรัสวดี).[26]

Literature

In Hinduism, Sarasvati has retained her significance as an important goddess, from the Vedic age up to the present day.[27] She is praised in the Vedas as a water goddess of purification, while in the Dharmashastras, Sarasvati is invoked to remind the reader to meditate on virtue, and on the meaning (artha) of one's actions (karma).

In Vedic literature

Rigveda

Sarasvati first appears in the Rigveda, the most ancient source of the Vedic religion. Sarawsati holds significant religious and symbolic value in the Rigveda, as a deified entity embodying attributes of abundance and power. Primarily linked with the celestial domain of Waters (Apas) and the formidable Storm Gods (Maruts), this deity forms an integral triadic association alongside the sacrificial goddesses Ila and Bharati within the pantheon.[28]

Sarasvati is described as a loud and powerful flood who roars like a bull and cannot be controlled.[29] According to Witzel, she was associated with the Milky Way, indicating that she was seen as descending from heaven to earth.[30]

The goddess is mentioned in many Rigvedic hymns, and has three hymns dedicated to her (6:61 exclusively, and 7:95-96 which she shares with her male counterpart, Sarasvant).[28] In Rigveda 2.41.16 she is called: "Best of mothers, the best of rivers, best of goddesses".[31]

As part of the Apas (water deities), Sarasvati is associated with wealth, abundance, health, purity and healing.[32] In Book 10 (10.17) of the Rigveda, Sarasvati is celebrated as a deity of healing and purifying water.[33] In the Atharva Veda, her role as a healer and giver of life is also emphasized.[34] In various sources, including the Yajur Veda, she is described as having healed Indra after he drank too much Soma.[35]

Sarasvati also governs dhī (Rigveda 1:3:12c.).[36] Dhī is the inspired thought (especially that of the rishis), it is intuition or intelligence – especially that associated with poetry and religion. Sarasvati is seen as a deity that can grant dhī (Rigveda 6:49:7c.) if prayed to.[28] Since speech requires inspired thought, she is also inextricably linked with speech and with the goddess of speech, Vāc, as well as with cows and motherhood.[37] Vedic seers compare her to a cow and a mother, and saw themselves as children sucking the milk of dhī from her.[38] In Book 10 of the Rigveda, she is declared to be the "possessor of knowledge".[39] In later sources, like the Yajur Veda, Sarasvati is directly identified with Vāc, becoming a deity called Sarasvatī-Vāc.[40]

In the Brahmanas, Sarasvati-Vac's role expands, becoming clearly identified with knowledge (which is what is communicated through speech) and as such, she is "the mother of the Vedas" as well as the Vedas themselves.[41] The Shatapatha Brahmana states that "as all waters meet in the ocean...so all sciences (vidya) unite (ekayanam) in Vāc" (14:5:4:11).[42] The Shatapatha Brahmana also presents Vāc as a secondary creator deity, having been the first deity created by the creator god Prajapati. She is the very instrument by which he created the world, flowing forth from him "like a continuous stream of water" according to the scripture.[42] This is the basis for the Puranic stories about the relationship between Brahma (identified with Prajapati) and Sarasvati (identified with Vāc).[43]

In other Rigvedic passages, Sarasvati is praised as a mighty and unconquerable protector deity. She is offered praises and compared to a sheltering tree in Rigveda 7.95.5, while in 6:49:7 cd she is said to provide "protection which is difficult to assail."[44][45] In some passages she even takes a fiercesome appearance and is called a "slayer of strangers" who is called on to "guard her devotees against slander".[46] Her association with the combative storm gods called Maruts is related to her fierce fighting aspect and they are said to be her companions (at Rigveda 7:96:2c.).[47]

Like Indra, Sarasvati is also called a slayer of Vritra, the snake like demon of drought who blocks rivers and as such is associated with destruction of enemies and removal of obstacles.[48] The Yajur Veda sees her as being both the mother of Indra (having granted him rebirth through healing) and also as his consort.[49]

The Yajur Veda also contains a popular alternative version of the Gayatri Mantra focused on Sarasvati:[50][51]

Om. May we know Sarasvati. May we meditate on the daughter of Brahma. May the Goddess illuminate us.

In Book 2 of Taittiriya Brahmana, Sarasvati is called "the mother of eloquent speech and melodious music".[22]

Epic literature

In the Hindu epic Mahabharata, "Sarasvati appears above all as a sacred river, along which pilgrimages are made. She is also represented as goddess of speech and knowledge."[52] She is called "the best of rivers and greatest of streams", and with calm and tranquil waters, in contrast to the mighty torrential Vedic Sarasvati.[52] Her banks are filled with priests and sages (rishis) who practice asceticism and sacrifices on her banks.[53] There are numerous depictions of people making pilgrimages to the river to perform sacrifices and bathe in her waters and she often appears in her human form to great seers like Vasishtha.[54]

The Mahabharata also commonly presents her as a goddess of knowledge in her own right and sees Vac as merely a feature of hers.[55] She is called the mother of the Vedas in the Shanti Parva Book of the epic.[19] Her beauty is also widely commented on by numerous passages and in one passage, the goddess herself states that her knowledge and her beauty arise from gifts made in the sacrifice.[56] The Mahabharata also describes her as the daughter of the creator god Brahma.[57] Later she is described as the celestial creative symphony who appeared when Brahma created the universe.[19]

In the epic Ramayana, when the rakshasa brothers Ravana, Vibhishana and Kumbhakarna, performed a penance in order to propitiate Brahma, the creator deity offered each a boon. The devas pleaded with Brahma to not grant Kumbhakarna his boon. Brahma called upon his consort Sarasvati, and instructed her to utter that which the devas desired. She acquiesced, and when the rakshasa spoke to invoke his boon, she entered his mouth, causing him to say, "To sleep for innumerable years, O Lord of Lords, this is my desire!". She then left his form, causing him to reflect upon his misfortune.[58]

Puranic literature

Sarasvati remains an important figure in the later medieval Puranic literature, where she appears in various myths and stories. Many Puranas relate the myth of her creation by the creator god Brahma and then describe how she became his consort. Sources which describe this myth include Markandeya Purana, Matsya Purana (which contains the most extensive account), Vayu Purana and Brahmanda Purana.[59] Other Puranas give her slightly different roles and see her as the consort of other gods, such as Vishnu. In various Puranas, rites for her worship are given, and she is mainly worshiped for her command over speech, knowledge, and music.[60]

Puranas like the Matsya also contain iconographic descriptions of Sarasvati, which provide the basis for her classic four armed form holding a book (representing the Vedas), mala, veena, and a water pot while being mounted on a swan (hamsa).[61]

Association with Brahma

According to the Matsya Purana, Brahma generated Sarasvati, here also called by other names like Shatarupa, Savitri, Gayatri and Brahmani, out of himself for the purpose of creation.[62]

The Matsya Purana then describes how Brahma begins to desire her intensely and cannot stop looking at her. Noticing his amorous glances, she begins circumambulating him. Not wishing to keep turning his face to see her, Brahma produced faces on the sides and back of his head. Sarasvati then leapt into the sky and a fifth face emerged from Brahma, looking upwards. Unable to escape, Sarasvati marries him and they make love for one hundred years.[63][64] Brahma felt shame and due to his incestuous act, the god loses his ascetic power (tapas) and his sons are left to create the world.[65]

The birth of Sarasvati from the mind of Brahma is also described in the Brahmanda Purana (chapter 43). Sarasvati is tasked to reside on tip of the tongue of all beings, a river on the earth and as a part of Brahma.[64]

In the Bhagavata Purana

A legend in the Bhagavata Purana describes Sarasvati as originally being one of the three wives of Vishnu, along with Lakshmi and Ganga. In the midst of a conversation, Sarasvati observed that Ganga playfully kept glancing at Vishnu, behind Lakshmi and her back. Frustrated, Sarasvati launched a furious tirade against Ganga, accusing her of stealing Vishnu's love away from her. When Ganga appealed to her husband to help her, he opted to remain neutral, not wishing to participate in a quarrel between his three wives, whom he loved equally. When Lakshmi attempted to soothe Sarasvati's anger by reasoning with her, the jealous goddess grew angry with her as well, accusing her of disloyalty towards her. She cursed Lakshmi to be born as the Tulasi plant upon the earth. Ganga, now enraged that Lakshmi had been cursed because she had defended her, cursed Sarasvati that she would be incarnated as a river on earth. Sarasvati issued the same curse against Ganga, informing her that sinful men would cleanse themselves of their sins with her water. As a result, Vishnu proclaimed that one part of Sarasvati would remain with him, that another would exist as a river on earth, and that another would later become the spouse of Brahma.[66][67]

Puranic Narratives of Sarasvati’s River Aspect

In the Rigveda, Sarasvati is primarily depicted as a river goddess, embodying fertility and purity, and is revered as the personification of the Sarasvati River. Her role as the nurturing, life-giving force of the river is celebrated in hymns, where she is described as "the best of mothers, of rivers, and of goddesses."[68] A Rigvedic prayer also describes her as 'the best of mothers, of rivers and of goddesses'.[68] However, as Sarasvati’s association with knowledge, speech, and culture grew in prominence through the later Hindu texts, her direct connection with the physical river diminished. Despite this, the Puranas sustain Sarasvati's riverine character by incorporating new narratives that preserve her role as a cosmic river in addition to her expanded identity.[1]

The story of Sarasvati becoming a river is introduced in the Srishti Khanda of Padma Purana as well as in Skanda Purana. In the Skanda Purana, after the events of the Tarakamaya War, the devas deposited their arsenal of weapons at the hermitage of Dadhichi. When they sought the return of these weapons, the sage informed them that he had imbibed all of their power with his penance, and offered his own bones instead, which could serve as the source of new weapons. Despite the objections of the deities, the sage sacrificed himself, and his bones were employed in the manufacture of new arms by Vishvakarma. The sage's son, Pippalada, upon hearing these events, sought to wreak his vengeance on the devas by performing a penance. A mare emerged from his right thigh, which in turn gave birth to a fiery man, Vadava, who threatened to be the doom of all of creation. Vishnu convinced Vadava that his best course of action would be to swallow the devas one by one, and that he should begin by consuming the primordial water of creation, which was the foremost of both the devas and the asuras. Vadava wished to be accompanied to the source of these waters by a virgin, and so Sarasvati was dispatched for his purpose, despite her reluctance. She took him to Varuna, the god of the ocean, who then consumed the being. For good measure, Sarasvati transformed into a divine river, flowing with five channels into the sea, making the waters sacred.[69]

In the Padma Purana, it is stated that there was a terrible battle between the Bhargavas (a group of Brahmanas) and the Hehayas (a group of Kshatriyas). From this, an all-consuming fire called Vadavagni was born, which threatened to destroy the whole world. In some versions, a sage named Auva created it. Indra, Vishnu, and the devas visited Sarasvati, requesting her to deposit the fire in the western ocean, in order to protect the universe.[70][71] Sarasvati told Vishnu that she would only agree to assist them if her consort, Brahma, told her to do so. Brahma ordered her to deposit the Vadavagni in the western ocean. Sarasvati agreed, and accompanied by Ganga, she left Brahmaloka, and arrived at Sage Uttanka's ashrama. There, she met Shiva, who had decided to carry Ganga. He gave the Vadavagni in a pot to Sarasvati, and told her to originate from the plaksha tree. Sarasvati merged with the tree, and transformed into a river. From there, she flowed towards Pushkara. Sarasvati continued her journey towards the ocean, and stopped once at Pushkarini, where she redeemed humans from their sins. At last, she reached the end of her journey, and immersed the fire into the ocean.[72][73]

Shakta texts

Sarasvati is a key figure in the Indian goddess centered traditions which are today known as Shaktism. Sarasvati appears in the Puranic Devi Mahatmya (Glory of the Goddess), a central text for Shaktism which was appended to the Markandeya Purana during the 6th century CE.[74] In this text, she is part of the "triple goddess" (Tridevi) along with Mahakali, and Mahalakshmi.[9] In Shaktism, this trinity (the Shakta response to the male trimurti of the other Hindu sects) is a manifestation of Mahadevi, the supreme goddess (and the highest deity out of which all deities, male or female, are born), which is also known by other names like Adi Parashakti ("Primordial Supreme Power").[75][76]

According to the Devi Mahatmya, this supreme goddess is the primordial creator which is supreme formless (nirguna) consciousness (i.e. parabrahman, absolute reality) and the tridevi are her main saguna ("with form", manifest, incarnated) emanations.[77] MahaSarasvati is said to be creative and active principle (which is Rajasic, energetic and active), while Mahalakshmi is the sustainer (sattvic, "goodness") and Mahakali is the destroyer (tamasic, "darkness").[77]

In other influential Shakta texts, such as the Devi Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Upanishad, Sarasvati (along with all Hindu goddesses) is also said to be a manifestation of the supreme Mahadevi.[8]

In Tantric Shakta sources, Sarasvati takes many forms. A key tantric form is Matangi, a deity considered to be the "Tantric Sarasvati". Mātaṅgī retains many attributes of Sarasvati, like music and learning, but is also associated with defeating enemies, disease, pollution/impurity, and outcasts (chandalas).[78] She is often offered half eaten or leftover food and is green in color. Matangi is also part of the Shakta set of goddesses known as the ten Mahavidyas.

Matangi is important in Shri Vidya Shaktism, where she is also known as the dark blue Shyamala ("dark in complexion") and is a manifestation of Lalita Tripurasundari's Jñana Shakti (wisdom power), having arisen out of Lalita's sugarcane bow.[79] She is celebrated in the holiday Syamala Navaratri and is seen as Lalita's prime minister. There are various chants and odes (stotras) to this deity, perhaps the most important being the Śrī Śyāmalā Daṇḍakam by the great Indian Sanskrit poet Kalidasa.[80][81]

Symbolism and iconography

The goddess Sarasvati is often depicted as a beautiful woman dressed in pure white, often seated on a white lotus, which symbolizes light, knowledge and truth.[82] She not only embodies knowledge but also the experience of the highest reality. Her iconography is typically in white themes from dress to flowers to swan – the colour symbolizing Sattwa Guna or purity, discrimination for true knowledge, insight and wisdom.[1][83]

Her dhyana mantra describes her to be as white as the moon, clad in a white dress, bedecked in white ornaments, radiating with beauty, holding a book and a pen in her hands (the book represents knowledge).[84]

She is generally shown to have four arms, but sometimes just two. When shown with four hands, those hands symbolically mirror her husband Brahma's four heads, representing manas (mind, sense), buddhi (intellect, reasoning), citta (imagination, creativity), and ahamkāra (self consciousness, ego).[85][86] Brahma represents the abstract, while she represents action and reality.

- The variations in iconography of Sarasvati with various musical instruments

The four hands hold items with symbolic meaning – a pustaka (book or script), a mālā (rosary, garland), a water pot and a musical instrument (vīnā).[1] The book she holds symbolizes the Vedas representing the universal, divine, eternal, and true knowledge as well as all forms of learning. A mālā of crystals, representing the power of meditation, inner reflection, and spirituality. A pot of water represents the purifying power to separate right from wrong, the clean from the unclean, and essence from the inessential. In some texts, the pot of water is symbolism for soma – the drink that liberates and leads to knowledge.[1] The most famous feature on Sarasvati is a musical instrument called a veena, represents all creative arts and sciences,[85] and her holding it symbolizes expressing knowledge that creates harmony.[1][87] Sarasvati is also associated with anurāga, the love for and rhythm of music, which represents all emotions and feelings expressed in speech or music.

A hamsa – either a swan or a goose – is often shown near her feet. In Hindu mythology, the hamsa is a sacred bird, which if offered a mixture of milk and water, is said to have a unique ability to separate and drink the milk alone, and leave the water behind. This characteristic of the bird serves as a metaphor for the pursuit of wisdom amidst the complexities of life, the ability to discriminate between good and evil, truth from untruth, essence from the outward show, and the eternal from the evanescent.[85] Due to her association with the swan, Sarasvati is also referred to as Hamsavāhini, which means "she who has a hamsa as her vehicle". The swan is also a symbolism for spiritual perfection, transcendence and moksha.[83][88]

Sometimes a citramekhala (also called mayura, peacock) is shown beside the goddess. The peacock symbolizes colorful splendor, the celebration of dance, and – as the devourer of snakes – the alchemical ability to transmute the serpent poison of self into the radiant plumage of enlightenment.[89]

Forms and avatars

Many different avatars and forms of Sarasvati have been attested in scriptures.

She is venerated as MahaSarasvati in the Kashmir Shakti Peetha, as Vidhya Sarasvati in Basara and Vargal, and as Sharadamba in Sringeri. In some regions, she is known by her twin identities, Savitri and Gayatri.

In Shaktism, she takes her Matrika (mother goddess) avatar as Brahmani. Sarasvati is not just the goddess of knowledge and wisdom, but also the Brahmavidya herself, the goddess of the wisdom of ultimate truth. Her Mahavidya form is Matangi.

- Vidhya, she is the formless concept of wisdom and knowledge in all of its aspects.

- Gayatri, she is the personification of the Vedas

- Savitri, She is the personification of purity, the consort of Brahma

Maha Sarasvati

In some regions of India, such as Vindhya, Odisha, West Bengal and Assam, as well as east Nepal, Sarasvati is part of the Devi Mahatmya Shakta mythology, in the Tridevi of Mahakali, Mahalakshmi and MahaSarasvati.[9][90] This is one of many different Hindu legends that attempt to explain how the Hindu trimurti of gods (Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva) and goddesses (Sarasvati, Lakshmi and Parvati) came into being. Various Purana texts offer alternate legends for Maha Sarasvati.[91]

Maha Sarasvati is depicted as eight-armed and is often portrayed holding a Veena whilst sitting on a white lotus flower.

Her meditation verse given at the beginning of the fifth chapter the Devi Mahatmya is:

Wielding in her lotus-hands the bell, trident, ploughshare, conch, pestle, discus, bow, and arrow, her lustre is like that of a moon shining in the autumn sky. She is born from the body of Gauri and is the sustaining base of the three worlds. That MahaSarasvati I worship here who destroyed Sumbha and other asuras.[92]

MahaSarasvati is also part of another legend, the Navshaktis (not to be confused with Navdurgas), or nine forms of Shakti, namely Brahmi, Vaishnavi, Maheshwari, Kaumari, Varahi, Narsimhi, Aindri, Shivdooti, and Chamunda, revered as powerful and dangerous goddesses in eastern India. They have special significance on Navaratri in these regions. All of these are seen ultimately as aspects of a single great Hindu goddess, Durga, with Maha Sarasvati as one of those nine.[93]

Mahavidya Nila Sarasvati

In Tibet and parts of India, NilaSarasvati is sometimes considered as a form of Mahavidya Tara. Nila Sarasvati is not much a different deity from traditional Sarasvati, who subsumes her knowledge and creative energy in tantric literature. Though the traditional form of Sarasvati is of calm, compassionate, and peaceful one: Nila Sarasvati is the ugra (angry, violent, destructive) manifestation in one school of Hinduism, while the more common Sarasvati is the saumya (calm, compassionate, productive) manifestation found in most others. In tantric literature of the former, NilaSarasvati has 100 names. There are separate dhyana shlokas and mantras for her worship in Tantrasara.[27] She is worshipped in parts of India as an incarnate or incarnation of Goddess Tara but mostly outside India. She is not only worshipped but also been manifested as a form of Goddess Sarasvati.[clarification needed][citation needed]

Sharada avatar in Kashmir

The earliest known shrine dedicated to goddess worship in Kashmir is Sharada Peeth (6th–12th centuries CE), dedicated to the goddess Sharada. It is a ruined Hindu temple and ancient centre of learning located in present-day Azad Kashmir. The goddess Sharada worshipped in Sharada Peeth is a tripartite embodiment of the goddess Shakti: Sharada (goddess of learning), Sarasvati (goddess of knowledge), and Vagdevi (goddess of speech, which articulates power).[94] Kashmiri Pandits believe the shrine to be the abode of the goddess.[12] In line with the Kashmiri Pandit belief that springs which are the abode of goddesses should not be looked at directly, the shrine contains a stone slab concealing the spring underneath, which they believe to be the spring in which the goddess Sharada revealed herself to the rishi Shandilya. It advanced the importance of knowledge and education in Kashmiri Pandit culture, which persisted well after Kashmiri Pandits became a minority group in Kashmir.[95]

As one of the Maha Shakti Peethas, Hindus believe that it represents the spiritual location of the goddess Sati's fallen right hand. Sharada Peeth is one of the three holiest sites of pilgrimage for Kashmiri Pandits, alongside the Martand Sun Temple and the Amarnath Temple.

Worship

Temples

There are many Hindu temples dedicated to Sarasvati around the world. Some notable temples include the Gnana Sarasvati Temple in Basar on the banks of the River Godavari, the Wargal Sarasvati and Shri Sarasvati Kshetramu temples in Medak, Telangana. In Karnataka, one of many Sarasvati/Sharada pilgrimage spots is Shringeri Sharadamba Temple. In Ernakulam district of Kerala, there is a famous Sarasvati temple in North Paravur, namely, Dakshina Mookambika Temple North Paravur. In Tamil Nadu, Koothanur hosts a Sarasvati temple. In her identity as Brahmani, additional Sarasvati temples can be found throughout Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. Jnaneshwari Peeth in Karki village of coastal Karnataka also houses a temple dedicated to Sarasvati, where she is known as Jnaneshwari.[citation needed]

Festivals and pujas

One of the most famous festivals associated with Goddess Sarasvati is the Hindu festival of Vasant Panchami. Celebrated on the 5th day in the Hindu calendar month of Magha, it is also known as Sarasvati Puja and Sarasvati Jayanti in India.

In south India

In Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the last three days of the Navaratri festival, i.e., Ashtami, Navami, and Dashami, are celebrated as Sarasvati Puja.[96]

The celebrations start with the Puja Vypu (Placing for Worship). It consists of placing the books for puja on the Ashtami day. It may be in one's own house, in the local nursery school run by traditional teachers, or in the local temple. The books are taken out for reading, after worship, only on the morning of the third day (Vijaya Dashami). It is called Puja Eduppu (Taking [from] Puja). On the Vijaya Dashami day, Kerala and Tamil Nadu celebrate the Eḻuthiniruthu or "Initiation of writing" for children, before they are admitted to nursery schools. This is also called Vidyarambham. The child is often ritually taught to write for the first time on rice spread in a plate with their index finger, guided by an elder of the family, or by a teacher.[97]

In east and northeast India

In Assam, Odisha, West Bengal and Tripura, Goddess Sarasvati is worshipped on Vasant Panchami, a Hindu festival celebrated every year on the 5th day in the Hindu calendar month of Magha (about February). Hindus celebrate this festival in temples, homes and educational institutes alike.[98][99]

In north, west, and central India

In Bihar and Jharkhand, Vasant Panchami is commonly known as Sarasvati Puja. On this day, Goddess Sarasvati is worshipped in schools, colleges, educational institutes as well as in institutes associated with music and dance. Cultural programmes are also organised in schools and institutes on this day. People especially students worship Goddess Sarasvati also in pandals (a tent made up of colourful clothes, decorated with lights and other decorative items). In these states, on the occasion of Sarasvati Puja, Goddess Sarasvati is worshipped in the form of idol, made up of soil. On Sarasvati Puja, the idol is worshipped by people and prasad is distributed among the devotees after puja. Prasad mainly consists of boondi (motichoor), pieces of carrot, peas and Indian plum (ber). On the next day or any day depending on religious condition, the idol is immersed in a pond (known as Murti Visarjan or Pratima Visarjan) after performing a Havana (immolation), with full joy and fun, playing with abir and gulal. After Pratima Visarjan, members involved in the organisation of puja ceremony eat khichdi together.[citation needed]

In Goa, Sarasvati Puja starts with Sarasvati Avahan on Maha Saptami and ends on Vijayadashami with Sarasvati Udasan or Visarjan.[100]

In 2018, the Haryana government launched and sponsored the annual National Sarasvati Mahotsav in its state named after Sarasvati.[101]

In Indonesia

Watugunung, the last day of the pawukon calendar, is devoted to Sarasvati, goddess of learning. Although it is devoted to books, reading is not allowed. The fourth day of the year is called Pagerwesi, meaning "iron fence". It commemorates a battle between good and evil.[102]

Sarasvati is an important goddess in Balinese Hinduism. She shares the same attributes and iconography as Sarasvati in Hindu literature of India – in both places, she is the goddess of knowledge, creative arts, wisdom, language, learning and purity. In Bali, she is celebrated on Sarasvati day, one of the main festivals for Hindus in Indonesia.[103][104] The day marks the close of 210 day year in the Pawukon calendar.[105]

On Sarasvati day, people make offerings in the form of flowers in temples and to sacred texts. The day after Sarasvati day, is Banyu Pinaruh, a day of cleansing. On this day, Hindus of Bali go to the sea, sacred waterfalls or river spots, offer prayers to Sarasvati, and then rinse themselves in that water in the morning. Then they prepare a feast, such as the traditional bebek betutu and nasi kuning, that they share.[106]

The Sarasvati Day festival has a long history in Bali.[107] It has become more widespread in Hindu community of Indonesia in recent decades, and it is celebrated with theatre and dance performance.[105]

Southeast Asia

Sarasvati was honoured with invocations among the Hindus of Angkorian Cambodia.[108] She and Brahma are referred to in Cambodian epigraphy from the 7th century onwards, and she is praised by Khmer poets for being the goddess of eloquence, writing, and music. More offerings were made to her than to her husband Brahma. She is also referred to as Vagisvari and Bharati in the Khmer literature of the era of Yasovarman, Hindu king of the Khmer Empire.[108]

In Buddhism

In Buddhism, Sarasvati became a prominent deity which retained many of her Vedic associations, such as speech, texts, knowledge, healing and protection. She also became known as the consort of Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom (prajña). According to Miranda Shaw's Buddhist Goddesses of India:

Sarasvati's association with the intellectual sphere assured that she would find favor among Buddhists, who highly value wisdom and its servants: mental clarity, reasoning ability, memorization, and oratorical skill. Sarasvati thus has an affinity with Prajñaparamita, the goddess of perfect wisdom. They may be in voked by the same mantra, reflecting the kinship between the wisdom goddess and the patroness of learning.[109]

Shaw lists various epithets for Sarasvati used by Buddhist source including: "Emanation of Vishnu," "Gandharva Maiden," "Swan Child," "Daughter of Brahma", "Lady of the Lake", "Sister of the Moon", "Goddess of Speech", "Divine Lady Who Empowers Enlightened Speech", "Goddess Rich with the Power of Adamantine Speech", "Bestower of Understanding", "Goddess of Knowledge", and "Wisdom Goddess."[109] According to Shaw, Buddhist depictions of Sarasvati are influenced by Hindu ones. A popular depiction is called "Lady of the Adamantine Lute" (Vajravina) which is described by Shaw as.

a white, two-armed epiphany in which she plays her supernal lute, or vina. The instrument is made of lapis lazuli and has a thousand strings capable of eliciting every musical note. Sarasvati's melodies pervade the universe and delight all types of beings in accordance with whatever is most pleasing to their ears. She sits with ankles crossed and knees raised in a distinctive posture suitable for balancing a musical instrument.[110]

According to Catherine Ludvik, Sarasvati's earliest appearance in a Buddhist text is in the 1st century CE Mahayana Golden Light Sutra (of which there are different versions / translations). This text is first attested in a Chinese translation in 417 CE and includes an entire chapter devoted to the goddess, which is our best source for the earliest Buddhist depictions of Sarasvati.[111]

In the Golden Light Sutra

In the Golden Light Sutra (Suvarṇaprabhāsa Sūtra), Sarasvati appears and pays homage to the Buddha. As Shaw writes, she then "promises that she will grace the preachers of the scripture with eloquence, oratorical power, perfect memory, inconceivable knowledge, penetrating wisdom, illumination, skill in liberating others, scholarly expertise in every field, proficiency in all the arts, merit, prosperity, and long life."[112]

Sarasvati's chapter in the Golden Light Sutra presents three main aspects of the goddess. First, it presents her as a goddess of eloquence and speech, then it presents her as a healing goddess who teaches a ritual which includes a medicinal bath, finally it presents Sarasvati as a goddess of protection and war.[113] Ludvik mentions that the earliest version of the Golden Light Sutra (the translation by Dharmaksema) actually only includes the first depiction.[113] The early Chinese Buddhist translators chose to translate her name as "great eloquence deity" (大辯天) the later translations by Yijing use "Eloquence Talent Goddess" (Biancai tiannu), though phonetic translations were also applied (e.g. Yijing's "mohetipi suoluosuobodi").[113]

In the Golden Light Sutra, Sarasvati is closely associated with eloquence, as well as with the closely connected virtues of memory and knowledge.[114] Sarasvati is also said to help monks memorize the Buddhist sutras and to guide them so they will not make mistakes in memorizing them or forget them later. She will also help those who have incomplete manuscripts to regain the lost letters or words. She also teaches a dharani (a long mantra-like recitation) to improve memory.[115] The Golden Light goes as far as to claim that Sarasvati can provide the wisdom to understand all the Buddhist teachings and skillful means (upaya) so that one may swiftly attain Buddhahood.[116]

In some versions of the Golden Light Sutra, such as Yijing's, the goddess then teaches an apotropaic ritual that can combat disease, bad dreams, war, calamities and all sorts of negative things. It includes bathing in a bath with numerous herbs that has been infused with a dharani spell. This passage contains much information on ancient materia medica and herbology.[117] Ludvik adds that this may be connected to her role as healer of Indra in the Yajur Veda and to ancient Indian bathing rites.[118]

In the latter part of the Golden Light's Sarasvati chapter, she is praised as a protector goddess by the Brahman Kaundinya. This section also teaches a dharani and a ritual to invoke the goddess and receive her blessings in order to obtain knowledge.[119] In latter sections of Kaundinya's praise, she is described as an eight armed goddess and compared to a lion. The text also states that is some recites these praises, "one obtains all desires, wealth and grain, and one gains splendid, noble success."[120] The poem describes Sarasvati as one who "has sovereignty in the world", and states that she fights in battlefields and is always victorious.[121] The hymn then describes Sarasvati's warlike eight-armed form. She carries eight weapons in each hand – a bow, arrow, sword, spear, axe, vajra, iron wheel, and noose.[122]

Kaudinya's hymn to Sarasvati in Yijing's translation is derived from the Āryāstava ("praise of she who is noble"), a hymn uttered by Vishnu to the goddess Nidra (lit. "Sleep", one of the names applied to Durga) found in the Harivamsha.[123] As the Golden Light Sutra is often concerned with the protection of the state, it is not surprising that the fierce, weapon-wielding Durga, who was widely worshiped by rulers and warriors alike for success in battle, provides the model for the appearance assumed by Sarasvati, characterized as a protectress of the Buddhist Dharma.[124] Bernard Faure argues that the emergence of a martial Sarasvatī may have been influenced by the fact that "Vāc, the Vedic goddess of speech, had already displayed martial characteristics. [...] Already in the Vedas, it is said that she destroys the enemies of the gods, the asuras. Admittedly, later sources seem to omit or downplay that aspect of her powers, but this does not mean that its importance in religious practice was lost."[125]

Other Indian Mahayana sources

In some later Mahayana Buddhist sources like the Sādhanamālā (a 5th-century collection of ritual texts), Sarasvati is symbolically represented in a way which is similar to Hindu iconography.[16] The description of the deity (here called Mahāsarasvatī) is as follows:

The worshipper should think himself as goddess Mahāsarasvatī, who is resplendent like the autumn moon, rests on the moon over the white lotus, shows the varada-mudrā in her right hand, and carries in the left the white lotus with its stem. She has a smiling countenance, is extremely compassionate, wears garments decorated with white sandal-flowers. Her bosom is decorated with the pearl-necklace, and she is decked in many ornaments; she appears a maiden of twelve years, and her bosom is uneven with half-developed breasts like flower-buds; she illumines the three worlds with the immeasurable light that radiates from her body.[126]

In the Sādhanamālā, the mantra of Sarasvati is: oṃ hrīḥ mahāmāyāṅge mahāsarasvatyai namaḥ

The Sādhanamālā also depicts other forms of Sarasvati, including Vajravīṇā Sarasvatī (similar to Mahāsarasvatī except she carries a veena), Vajraśāradā Sarasvatī (who has three eyes, sits on a white lotus, her head is decorated by a crescent and holds a book and a lotus), Vajrasarasvatī (has six hands and three heads with brown hair rising upwards), and Āryasarasvatī (sixteen-year-old girl carrying the Prajñapramita sutra and a lotus).[127]

According to the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra (c. 4th century – 5th century CE), Sarasvati was born from the eyetooth of Avalokiteshvara.[112]

Sarasvati is also briefly mentioned in the esoteric Vairochanabhisambodhi Sutra as one of the divinities of the western quarter of the Outer Vajra section of the Womb Realm Mandala along with Prithvi, Vishnu (Narayana), Skanda (Kumara), Vayu, Chandra, and their retinue. The text later also describes the veena as Sarasvati's symbol.[128][129] The Chinese translation of this sutra renders her name variously as 辯才 (Ch. Biàncái; Jp. Benzai, lit. "eloquence"),[130] 美音天 (Ch. Měiyīntiān; Jp. Bionten, "goddess of beautiful sounds"),[131] and 妙音天 (Ch. Miàoyīntiān; Jp. Myōonten, "goddess of wonderful sounds"[132]).[133] Here, Sarasvati is portrayed with two arms holding a veena and situated between Narayana's consort Narayani and Skanda (shown riding on a peacock).

Sarasvati was initially depicted as a single goddess without consort. Her association with the bodhisattva of wisdom Manjusri is drawn from later tantric sources such as the Kṛṣṇayamāri tantra, where she is depicted as red skinned (known as "Red Sarasvati").[134]

In various Indian tantric sadhanas to Sarasvati (which only survive in Tibetan translation), her bija (seed) mantra is Hrīḥ.[135]

Nepalese Buddhism

Sarasvati is worshiped in Nepalese Buddhism, where she is a popular deity, especially for students. She is celebrated in an annual festival called Vasant Pañcami and children first learn the alphabet during a Sarasvati ritual.[136] In Nepalese Buddhism, her worship is often combined with that of Manjusri and many sites for the worship of Manjusri are also used to worship Sarasvati, including Svayambhu Hill.[136]

In East Asian Buddhism

Veneration of Sarasvati migrated from the Indian subcontinent to China with the spread of Buddhism, where she in known as Biàncáitiān (辯才天), meaning "Eloquent Devī", as well as Miàoyīntiān (妙音天), meaning "Devī of Wonderful Sounds".[137]

She is commonly enshrined in Chinese Buddhist monasteries as one of the Twenty-Four Devas, a group of protective deities who are regarded as protectors of the Buddhist dharma. Her Chinese iconography is based on her description in the Golden Light Sutra, where she is portrayed as having eight arms, one holding a bow, one holding arrows, one holding a knife, one holding a lance, one holding an axe, one holding a pestle, one holding an iron wheel, and one holding ropes. In another popular Buddhist iconographic form, she is portrayed as sitting down and playing a pipa, a Chinese lute-like instrument.[138] The concept of Sarasvati migrated from India, through China to Japan, where she appears as Benzaiten (弁財天, lit. "goddess of eloquence").[139] Worship of Benzaiten arrived in Japan during the 6th through 8th centuries. She is often depicted holding a biwa, a traditional Japanese lute musical instrument. She is enshrined on numerous locations throughout Japan such as the Kamakura's Zeniarai Benzaiten Ugafuku Shrine or Nagoya's Kawahara Shrine;[140] the three biggest shrines in Japan in her honour are at the Enoshima Island in Sagami Bay, the Chikubu Island in Lake Biwa, and the Itsukushima Island in Seto Inland Sea.

In Japanese esoteric Buddhism (mikkyo), the main mantra for this deity is:

Oṃ Sarasvatyai svāhā (Sino-Japanese: On Sarasabatei-ei Sowaka).[141][142]

In Indo-Tibetan Buddhism

In the Indo-Tibetan Buddhism of the Himalayan regions, Sarasvati is known as Yangchenma (Tibetan: དབྱངས་ཅན་མ, Wylie: dbyangs can ma, THL: yang chen ma),[143] which means '"Goddess of Melodious Voice". She is also called the Tara of Music (Tibetan: དབྱངས་ཅན་སྒྲོལ་མ, Wylie: dbyangs can sgrol ma, THL: yang chen dröl ma) as one of the 21 Taras. She is also considered the consort of Manjushri, bodhisattva of Wisdom.[144][145] Sarasvati is the divine embodiment & bestower of enlightened eloquence & inspiration. For all those engaged in creative endeavours in Tibetan Buddhism she is a patroness of the arts, sciences, music, language, literature, history, poetry & philosophy.

Sarasvati also became associated with the Tibetan deity Palden Lhamo (Glorious Goddess) who is a fierce protector deity in the Gelugpa tradition known as Magzor Gyalmo (the Queen who Repels Armies).[146] Sarasvati was the yidam (principal personal meditational deity) of 14th century Tibetan monk Je Tsongkhapa, who composed a devotional poem to her.[147][148]

Tibetan Buddhism teaches numerous mantras of Sarasvati. Her seed syllable is often Hrīṃ.[149] In a sadhana (ritual text) revealed by the great Tibetan female lama Sera Khandro, her mantra is presented as:[150]

Oṃ hrīṃ devi prajñā vārdhani ye svāhā

In South East Asian Buddhism

In Burmese Buddhism, Sarasvati is worshipped as Thurathadi (Burmese: သူရဿတီ), an important nat (Burmese deity) and is a guardian of the Buddhist scriptures (Tipitaka), scholars, students and writers.[151][152][153][154][155] Students in Myanmar often pray for her blessings before their exams.[154]: 327 She is an important deity to the esoteric weizzas (Buddhist wizards) of Burma.[156][157]

In ancient Thai literature, Sarasvati (Thai: สุรัสวดี; RTGS: Suratsawadi) is the goddess of speech and learning, and consort of Brahma.[158] Over time, Hindu and Buddhist concepts merged in Thailand. Icons of Sarasvati with other deities of India are found in old Thai wats.[159] Amulets with Sarasvati and a peacock are also found in Thailand.

In Jainism

Sarasvati is also revered in Jainism as the goddess of knowledge and is regarded as the source of all learning. She is known as Srutadevata, Sarada, and Vagisvari.[160] Sarasvati is depicted in a standing posture with four arms, one holding a text, another holding a rosary and the remaining two holding the Veena. Sarasvati is seated on a lotus with the peacock as her vehicle. Sarasvati is also regarded as responsible for dissemination of tirthankars sermon.[17] The earliest sculpture of Sarasvati in any religious tradition is the Mathura Jain Sarasvati from Kankali Tila dating from 132 CE.[161]

See also

- Aban, "the Waters", representing and represented by Aredvi Sura Anahita.

- Anahita – the Old Persian goddess of wisdom

- Arachosia name of which derives from Old Iranian *Harahvatī (Avestan Haraxˇaitī, Old Persian Hara(h)uvati-).

- Athena – the Greek goddess of wisdom and knowledge

- Koothanur Maha Saraswathi Temple

- Minerva – the Roman goddess of wisdom and knowledge

- Rhea – the Greek goddess consort of Cronos and mother of the gods and titans.

- Sága – the Norse goddess of learning and knowledge

- Saraswati Vandana Mantra

- Saraswati yoga

Notes

- ^ The hymn comprises the following four verses:[3]

- या कुन्देन्दुतुषारहारधवला या शुभ्रवस्त्रावृता।

- या वीणावरदण्डमण्डितकरा या श्वेतपद्मासना॥

- या ब्रह्माच्युत शंकरप्रभृतिभिर्देवैः सदा वन्दिता।

- सा मां पातु सरस्वती भगवती निःशेषजाड्यापहा॥

- yā kundendutuṣārahāradhavalā yā śubhravastrāvṛtā

- yā vīṇāvaradaṇḍamaṇḍitakarā yā śvetapadmāsanā

- yā brahmācyuta śaṃkaraprabhṛtibhirdevaiḥ sadā pūjitā

- sā māṃ pātu sarasvati bhagavatī niḥśeṣajāḍyāpahā

References

This article has an unclear citation style. (November 2023) |

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the divine feminine in the Hindu religious traditions. University of California Press. pp. 55–64. ISBN 0-520063392.

- ^ a b c "Sarasvati | Definition, Depictions, Worship, & River | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 12 August 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Shivakumar, K. N. (14 January 2021). Shlokas and Bhajans: with general knowledge and subhashitams. Sangeet Bharati. p. 9.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. Sarup & Sons. 1999. p. 1214. ISBN 978-81-7625-064-1.

- ^ "Female Hindu deities – the Tridevi - Nature of Ultimate Reality in Hinduism - GCSE Religious Studies Revision - Edexcel". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b Ludvik (2007), pp. 1, 11.

- ^ Guide to the collection. Birmingham Museum of Art. Birmingham, Alabama: Birmingham Museum of Art. 2010. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5. Archived from the original on 14 May 1998.

- ^ a b Pintchman, Tracy (14 June 2001). Seeking Mahādevī: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9049-5.

- ^ a b c Lochtefeld, James (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. A–M. Rosen. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark. "Saraswati". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Monaghan, Patricia (18 December 2009). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines: [2 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-313-34990-4.

- ^ a b Kaw, M. K., ed. (2004). Kashmir and its people: studies in the evolution of Kashmiri society. New Delhi: A.P.H. Pub. Corp. ISBN 81-7648-537-3. OCLC 55147377.

- ^ "Vasant Panchami Saraswati Puja". Know India – Odisha Fairs and Festivals. Archived from the original on 23 September 2014.

- ^ "The festival of Vasant Panchami: A new beginning". United Kingdom: Alan Barker. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015.

- ^ "5th Annual A World in Trance Festival Jayanthi Kumaresh: Invoking The Goddess Sarawati | TeRra Magazine". 30 March 2019. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b Donaldson, Thomas (2001). Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-81-7017-406-6.

- ^ a b Prasad 2017, p. 192.

- ^ "सुरस". Sanskrit English Dictionary. Koeln, Germany: University of Koeln. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Muir, John (1870). Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India – Their Religions and Institutions. Vol. 5. pp. 337–347 – via Google Books.

- ^ Moor, Edward (1810). The Hindu Pantheon. pp. 125–127 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Sarasvati, The Goddess of Learning". Stephen Knapp. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009.

- ^ a b Balf, Edward (1885). The Encyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. p. 534 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Sri Saraswathi Ashtottara Shatanamavali - śrī sarasvatī aṣṭōttaraśatanāmāvalī". Stotra Nidhi. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Mohan Lal, 1992, p. 4333.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil, 1975, p. 129.

- ^ Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the divine feminine in the Hindu religious traditions. University of California Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-520-06339-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the divine feminine in the Hindu religious traditions. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06339-2.

- ^ a b c Ludvik (2007), pp. 11, 26.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 11-12

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 13

- ^ "Rigveda". Book 2, Hymn 41, line 16. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 17.

- ^ "Rigveda". Book 10, Hymn 17. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p 40.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 45.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p 27.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 26, 31.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 31.

- ^ Colbrooke, H.T. Sacred writings of the Hindus. London, UK: Williams & Norgate. pp. 16–17. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 38, 53.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 59-60.

- ^ a b Ludvik (2007), p. 60.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 63-66.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 15.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (27 August 2021). "Rig Veda 7.95.5 [English translation]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 16-17.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp 22-23.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 47-48.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 51.

- ^ Swami Vishnu Devananda, Vishnu Devananda (1999). Meditation and Mantras, p. 77. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- ^ Sunil Bahirat, Sarasvati Gayatri, siddhayoga.org

- ^ a b Ludvik (2007), p. 97

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 99-100

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 101-105

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 112

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 114-115

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 116

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (27 September 2020). "Concerning the Penances practised by Dashagriva and his Brother [Chapter 10]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 117-118.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 127

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 131-133

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 119

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 120.

- ^ a b www.wisdomlib.org (28 January 2019). "Story of Sarasvatī". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 121.

- ^ Williams, George M. (27 March 2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. OUP USA. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ Sharma, Bulbul (June 2010). The Book of Devi. Penguin Books India. pp. 67–71. ISBN 978-0-14-306766-5.

- ^ a b Warrier, Shrikala (2014). Kamandalu: the seven sacred rivers of Hinduism. London: Mayur University London. p. 97.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (13 April 2021). "The Descent of Sarasvatī [Chapter 34]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ General, India Office of the Registrar (1965). Census of India, 1961: Gujarat. Manager of Publications.

- ^ Danino, Michel (2010). The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvatī. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-306864-8.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (28 January 2019). "Story of Sarasvatī". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ N. A. Deshpande (1 January 1988). Padma Purana Part 1 Srishti Khanda Motilal Banarsidass 1988.

- ^ Charles Dillard Collins (1988). The Iconography and Ritual of Siva at Elephanta: On Life, Illumination, and Being. SUNY Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-88706-773-0.

- ^ "Tridevi - the three supreme Goddess in Hinduism". Hindu FAQS | Get answers for all the questions related to Hinduism, the greatest religion!. 18 March 2015.

- ^ Hay, Jeff (6 March 2009). World Religions. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-7377-4627-3.

- ^ a b Thomas Coburn (2002). Katherine Anne Harper, Robert L. Brown (ed.). The Roots of Tantra. State University of New York Press. pp. 80–83. ISBN 978-0-7914-5305-6.

- ^ Kinsley, David R. (1988). "Tara, Chinnamasta and the Mahavidyas". Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition (1 ed.), p. 217. University of California Press. pp. 161–177. ISBN 978-0-520-06339-6.

- ^ Saligrama Krishna Ramachandra Rao (1990). The Tāntric Practices in Śrī-Vidyā: With Śrī Śāradā-chatuśśatī, p. 205. Kalpataru Research Academy.

- ^ Alok Jagwat; Mahakavi Kalidasa (2021). Sri Shyamala Dandakam: Syamala Dandakam. Bhartiya Ved Vigyan Parishad.

- ^ "Sri Shyamala Dandakam - śrī śyāmalā daṇḍakam". Stotra Nidhi. 24 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Ludvík, Catherine (2007). Sarasvatī, Riverine Goddess of Knowledge: From the Manuscript-carrying Vīṇā-player to the Weapon-wielding Defender of the Dharma. BRILL. p. 1.

- ^ a b Holm, Jean; Bowke, John (1998). Picturing God. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 99–101. ISBN 978-1-85567-101-0.

- ^ "Hinduism 101 Saraswati Symbolism". Hindu American Foundation (HAF). Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Pollock, Griselda; Turvey-Sauron, Victoria (2008). The Sacred and the Feminine: Imagination and sexual difference. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-1-84511-520-3.

- ^ For Sanskrit to English translation of the four words: "Monier Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary". Koeln, Germany: University of Koeln. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016.

- ^ Some texts refer to her as "goddess of harmony"; for example: Wilkes, John (1827). Encyclopaedia Londinensis. Vol. 22. p. 669 – via Google Books.

- ^ Schuon, Frithjof (2007). Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- ^ Werness, Hope B. (2007). Animal Symbolism in World Art. Continuum Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-0-8264-1913-2.

- ^ Eck, Diana L. (2013). India: A sacred geography. Random House. pp. 265–279. ISBN 978-0-385-53192-4.

- ^ Brown, C. Mackenzie (1990). The Triumph of the Goddess. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0364-8.

- ^ Glory of the Divine Mother (Devi Mahatmyam) by S.Sankaranarayanan. Prabha Publishers, Chennai. India.(ISBN 81-87936-00-2) Page. 184

- ^ Lochtefeld, James (15 December 2001). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. N–Z. Rosen. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ^ Raina, Mohini Qasba (2013). Kashur the Kashmiri Speaking People: Analytical Perspective. Singapore: Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4828-9947-4.

Goddess Sharda is believed to be the earliest representation of Shakti in the valley, which is embodying three separate manifestations of energ y, i.e. goddess of learning, fine arts and beauty.

- ^ "What about a university by Kashmiri Pandits? | Curriculum Magazine". Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "Navratri rituals: Golu, Saraswati Puja, Vidyarambham ..." The Deccan Chronicle. 5 October 2013. p. 4. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013.

- ^ "Thiruvananthapuram gears up for Vidyarambham day". The Hindu. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ^ Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A multicultural encyclopedia. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- ^ Knapp, Stephen (2006). "The Dharmic Festivals". The Power of the Dharma: An introduction to Hinduism and Vedic culture. iUniverse. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-595-83748-9.

- ^ Kerkar, Rajendra (5 October 2011). "Saraswati Puja: Worshipping knowledge, education". Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Haryana to celebrate Saraswati Mahotsav on Jan 28". The Daily Pioneer. 7 January 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018.

- ^ Eiseman (1989) pp 184–185

- ^ "Saraswati, day of knowledge descent". The Bali Times. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014.

- ^ Pande, G.C. India's Interaction with Southeast Asia. Vol. 1. pp. 660–661. ISBN 978-81-87586-24-1.

- ^ a b Zurbuchen, Mary Sabine (2014). The Language of Balinese Shadow Theater. Princeton University Press. pp. 49–57. ISBN 978-0-691-60812-9.

- ^ Kruger, Vivienne (22 April 2014). Balinese Food: The traditional cuisine & food culture of Bali. Tuttle. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-8048-4450-5.

- ^ Gonda, Jan. "Section 3: Southeast Asia Religions". Handbook of Oriental Studies. Brill Academic. p. 45. ISBN 978-90-04-04330-5.

- ^ a b Wolters, O.W. (1989). History, Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-9971-902-42-1.

- ^ a b Shaw (2006), p. 236.

- ^ Shaw (2006), p. 238.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 145.

- ^ a b Shaw (2006), p. 237.

- ^ a b c Ludvik (2007), p. 157

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 158

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 158-59

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 160-161

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 162-164.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 172.

- ^ Ludvik (2007), p. 190

- ^ Ludvik (2007), pp. 197-205

- ^ Ludvik, Catherine (2004). "A Harivaṃśa Hymn in Yijing's Chinese Translation of the Sutra of Golden Light". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 124 (4): 707–734. doi:10.2307/4132114. JSTOR 4132114.

- ^ Faure, Bernard (2015). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-8248-5772-1.

- ^ "AryAstavaH - hymn to Arya". Mahabharata Resources Page. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Ludvik (2007). pp. 265-267.

- ^ Faure (2015). pp. 168-169.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Benoytosh (1924). The Indian Buddhist Iconography Mainly Based on the Sādhanamālā and Other Cognate Tāntric Texts of Rituals, p. 151. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Benoytosh (1924). The Indian Buddhist Iconography Mainly Based on the Sādhanamālā and Other Cognate Tāntric Texts of Rituals, pp. 151-152. Oxford University Press.

- ^ The Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra (PDF). BDK English Tripiṭaka Series. Translated by Rolf W. Giebel. Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai; Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. 2005. pp. 33, 141.

- ^ Faure (2015). p. 166.

- ^ "大毘盧遮那成佛神變加持經 第1卷". CBETA Chinese Electronic Tripiṭaka Collection (漢文大藏經). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "大毘盧遮那成佛神變加持經 第2卷". CBETA Chinese Electronic Tripiṭaka Collection (漢文大藏經). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Pye, Michael (2013). Strategies in the study of religions. Volume two, Exploring religions in motion. Boston: De Gruyter. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-61451-191-5. OCLC 852251932.

- ^ "大毘盧遮那成佛神變加持經 第4卷". CBETA Chinese Electronic Tripiṭaka Collection (漢文大藏經). Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ Wayman, Alex (1984). Buddhist Insight: Essays, p. 435. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. (Buddhist Tradition Series).

- ^ Wayman, Alex (1984). Buddhist Insight: Essays, pp. 436-437. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. (Buddhist Tradition Series).

- ^ a b Shaw (2006), p. 244.

- ^ "佛教二十四诸天_中国佛教文化网". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "辯才天". buddhaspace.org. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Ludvik, Catherine (2001). From Sarasvati to Benzaiten (PDF) (Ph.D.). University of Toronto: National Library of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF download) on 11 September 2014.

- ^ Suzuki, T. (1907). "The seven gods of bliss". The Open Court. Vol. 7, no. 2. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Saroj Kumar Chaudhuri (2003). Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan, p. 54. Vedams eBooks (P) Ltd.

- ^ "Goddess Benzaiten, A-to-Z Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist / Shinto Statues". www.onmarkproductions.com. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Jamgon Mipham (2000). Mo: The Tibetan Divination System. Shambhala. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-55939-848-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Khenchen Palden Sherab (2007). Tara's Enlightened Activity: An oral commentary on the twenty-one praises to Tara. Shambhala. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-1-55939-864-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jampa Mackenzie Stewart (2014). The Life of Longchenpa: The Omniscient Dharma King of the Vast Expanse. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-8348-2911-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Buddhist Protector: Shri Devi, Magzor Gyalmo Main Page". www.himalayanart.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Tsongkhapa, Je (24 March 2015). Prayer to Sarasvati. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-86171-770-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kilty, Gavin (15 June 2001). The Splendor of an Autumn Moon: The devotional verse of Tsongkhapa. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-192-0. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

Also: Tsongkhapa, Je (24 March 2015). The Splendor of an Autumn Moon: The devotional verse of Tsongkhapa. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-86171-770-5. Retrieved 24 January 2018 – via Google Books. - ^ "White Sarasvatī Sādhana". www.lotsawahouse.org. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ "Sarasvatī Meditation and Mantra". www.lotsawahouse.org. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Chew, Anne-May (2005). The Cave-temples of Po Win Taung, Central Burma: Architecture, Sculpture and Murals. White Lotus Press. ISBN 978-974-480-045-9.

- ^ Myanmar (Burma). Lonely Planet Publications. 2000. ISBN 978-0-86442-703-8.

- ^ Silverstein, Josef (1989). Independent Burma at forty years. Monograph Southeast Asia Program. Vol. 4. Cornell University. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-87727-121-5.

- ^ a b Seekins, Donald (2006). Historical Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5476-5.

- ^ Badgley, John H.; Kyaw, Aye. Red peacocks: commentaries on Burmese socialist nationalism. Readworthy. ISBN 978-93-5018-162-1.

- ^ Scott, Sir James George (1910). The Burman: His Life and Notions. Macmillan and Company, limited.

- ^ Maung, Shwe Lu (1989). Burma, Nationalism and Ideology: An Analysis of Society, Culture, and Politics. University Press. ISBN 978-984-05-1114-3.

- ^ McFarland, George (1944). Thai-English Dictionary. Stanford University Press. p. 790. ISBN 978-0-8047-0383-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Patit Paban Mishra (2010). The History of Thailand. ISBN 978-0-313-34091-8.

- ^ S, Prasad (2019). River and Goddess Worship in India: changing perceptions and manifestations of sarasvati. New York: New York: Routledge. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-367-88671-4.

- ^ Kelting 2001.

Works cited

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sarasuati". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kelting, M. Whitney (2001). Singing to the Jinas: Jain Laywomen, Mandal Singing, and the Negotiations of Jain Devotion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803211-3.

- Kinsley, David (1998). Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The ten mahāvidyās. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1523-8.

- Lal, Mohan (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- Ludvik, Catherine (2007). Sarasvatī: Riverine Goddess of Knowledge. Brill's Indological Library. Vol. 27. BRILL.

- Prasad, R. U. S. (2017). River and Goddess Worship in India: Changing Perceptions and Manifestations of Sarasvati. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-80654-1.

- Sankaranarayanan, S. (2001). Glory of the Divine Mother (Devī Māhātmyam). India: Nesma Books. ISBN 81-87936-00-2.

- Shaw, Miranda (2006). Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1975). Tamil Literature. Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

Further reading

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Coexisting contemporary civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. INU societal research: Global communication without universal civilization. Vol. 1. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Debnath, Sailen. The Meanings of Hindu Gods, Goddesses and Myths. New Delhi: Rupa & Co. ISBN 978-81-291-1481-5.

- Saraswati, Swami Satyananda. Saraswati Puja for Children. ISBN 1-877795-31-3.

External links

- "Sarasvati". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 September 2024.

- "Sarasvati, The Goddess of Learning". Stephen Knapp.