High-fructose corn syrup

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), also known as glucose–fructose, isoglucose and glucose–fructose syrup,[1][2] is a sweetener made from corn starch. As in the production of conventional corn syrup, the starch is broken down into glucose by enzymes. To make HFCS, the corn syrup is further processed by D-xylose isomerase to convert some of its glucose into fructose. HFCS was first marketed in the early 1970s by the Clinton Corn Processing Company, together with the Japanese Agency of Industrial Science and Technology, where the enzyme was discovered in 1965.[3]: 5

As a sweetener, HFCS is often compared to granulated sugar, but manufacturing advantages of HFCS over sugar include that it is cheaper.[4] "HFCS 42" and "HFCS 55" refer to dry weight fructose compositions of 42% and 55% respectively, the rest being glucose.[5] HFCS 42 is mainly used for processed foods and breakfast cereals, whereas HFCS 55 is used mostly for production of soft drinks.[5]

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that it is not aware of evidence showing that HFCS is less safe than traditional sweeteners such as sucrose and honey.[5] Uses and exports of HFCS from American producers have grown steadily during the early 21st century.[6]

Food

[edit]In the United States, HFCS is among the sweeteners that have mostly replaced sucrose (table sugar) in the food industry.[7][8] Factors contributing to the increased use of HFCS in food manufacturing include production quotas of domestic sugar, import tariffs on foreign sugar, and subsidies of U.S. corn, raising the price of sucrose and reducing that of HFCS, creating a manufacturing-cost advantage among sweetener applications.[8][9] In spite of having a 10% greater fructose content,[10] the relative sweetness of HFCS 55, used most commonly in soft drinks,[5] is comparable to that of sucrose.[8] HFCS provides advantages in food and beverage manufacturing, such as simplicity of formulation, stability, and enabling processing efficiencies.[5][8][11]

HFCS (or standard corn syrup) is the primary ingredient in most brands of commercial "pancake syrup," as a less expensive substitute for maple syrup.[12] Assays to detect adulteration of sweetened products with HFCS, such as liquid honey, use differential scanning calorimetry and other advanced testing methods.[13][14]

Production

[edit]Process

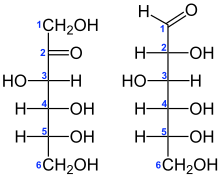

[edit]In the contemporary process, corn is milled to extract corn starch and an "acid-enzyme" process is used, in which the corn-starch solution is acidified to begin breaking up the existing carbohydrates. High-temperature enzymes are added to further metabolize the starch and convert the resulting sugars to fructose.[15]: 808–813 The first enzyme added is alpha-amylase, which breaks the long chains down into shorter sugar chains (oligosaccharides). Glucoamylase is mixed in and converts them to glucose. The resulting solution is filtered to remove protein using activated carbon. Then the solution is demineralized using ion-exchange resins. That purified solution is then run over immobilized xylose isomerase, which turns the sugars to ~50–52% glucose with some unconverted oligosaccharides and 42% fructose (HFCS 42), and again demineralized and again purified using activated carbon. Some is processed into HFCS 90 by liquid chromatography, and then mixed with HFCS 42 to form HFCS 55. The enzymes used in the process are made by microbial fermentation.[15]: 808–813 [3]: 20–22

Composition and varieties

[edit]HFCS is 24% water, the rest being mainly fructose and glucose with 0–5% unprocessed glucose oligomers.[16]

The most common forms of HFCS used for food and beverage manufacturing contain fructose in either 42% ("HFCS 42") or 55% ("HFCS 55") by dry weight, as described in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 184.1866).[5]

- HFCS 42 (approx. 42% fructose if water were ignored) is used in beverages, processed foods, cereals, and baked goods.[5][17]

- HFCS 55 is mostly used in soft drinks.[5]

- HFCS 70 is used in filling jellies[18]

Commerce and consumption

[edit]

The global market for HFCS is expected to grow from $5.9 billion in 2019 to a projected $7.6 billion in 2024.[19][dubious – discuss]

China

[edit]HFCS in China makes up about 20% of sweetener demand. HFCS has gained popularity due to rising prices of sucrose, while selling for a third the price. Production was estimated to reach 4,150,000 tonnes in 2017. About half of total produced HFCS is exported to the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India.[20]

European Union

[edit]In the European Union (EU), HFCS is known as isoglucose or glucose–fructose syrup (GFS) which has 20–30% fructose content compared to 42% (HFCS 42) and 55% (HFCS 55) in the United States.[21] While HFCS is produced exclusively with corn in the U.S., manufacturers in the EU use corn and wheat to produce GFS.[21][22] GFS was once subject to a sugar production quota, which was abolished on 1 October 2017, removing the previous production cap of 720,000 tonnes, and allowing production and export without restriction.[22] Use of GFS in soft drinks is limited in the EU because manufacturers do not have a sufficient supply of GFS containing at least 42% fructose content. As a result, soft drinks are primarily sweetened by sucrose which has a 50% fructose content.[23]

Japan

[edit]In Japan, HFCS is also referred to as 異性化糖 (iseika-to; isomerized sugar).[24] HFCS production arose in Japan after government policies created a rise in the price of sugar.[25] Japanese HFCS is manufactured mostly from imported U.S. corn, and the output is regulated by the government. For the period from 2007 to 2012, HFCS had a 27–30% share of the Japanese sweetener market.[26] Japan consumed approximately 800,000 tonnes of HFCS in 2016.[27] The United States Department of Agriculture states that HFCS is produced in Japan from U.S. corn. Japan imports at a level of 3 million tonnes per year, leading 20 percent of corn imports to be for HFCS production.[25]

Mexico

[edit]Mexico is the largest importer of U.S. HFCS.[28] HFCS accounts for about 27 percent of total sweetener consumption, with Mexico importing 983,069 tonnes of HFCS in 2018.[29][30] Mexico's soft drink industry is shifting from sugar to HFCS which is expected to boost U.S. HFCS exports to Mexico according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service report.[31]

On 1 January 2002, Mexico imposed a 20% beverage tax on soft drinks and syrups not sweetened with cane sugar. The United States challenged the tax, appealing to the World Trade Organization (WTO). On 3 March 2006, the WTO ruled in favor of the U.S. citing the tax as discriminatory against U.S. imports of HFCS without being justified under WTO rules.[32][33]

Philippines

[edit]The Philippines was the largest importer of Chinese HFCS. Imports of HFCS would peak at 373,137 tonnes in 2016. Complaints from domestic sugar producers would result in a crackdown on Chinese exports.[20] On 1 January 2018, the Philippine government imposed a tax of 12 pesos ($.24) on drinks sweetened with HFCS versus 6 pesos ($.12) for drinks sweetened with other sugars.[34]

United States

[edit]In the United States, HFCS was widely used in food manufacturing from the 1970s through the early 21st century, primarily as a replacement for sucrose because its sweetness was similar to sucrose, it improved manufacturing quality, was easier to use, and was cheaper.[8] Domestic production of HFCS increased from 2.2 million tons in 1980 to a peak of 9.5 million tons in 1999.[35] Although HFCS use is about the same as sucrose use in the United States, more than 90% of sweeteners used in global manufacturing is sucrose.[8]

Production of HFCS in the United States was 8.3 million tons in 2017.[36] HFCS is easier to handle than granulated sucrose, although some sucrose is transported as solution. Unlike sucrose, HFCS cannot be hydrolyzed, but the free fructose in HFCS may produce hydroxymethylfurfural when stored at high temperatures; these differences are most prominent in acidic beverages.[37] Soft drink makers such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi continue to use sugar in other nations but transitioned to HFCS for U.S. markets in 1980 before completely switching over in 1984.[38] Large corporations, such as Archer Daniels Midland, lobby for the continuation of government corn subsidies.[39]

Consumption of HFCS in the U.S. has declined since it peaked at 37.5 lb (17.0 kg) per person in 1999. The average American consumed approximately 22.1 lb (10.0 kg) of HFCS in 2018,[40] versus 40.3 lb (18.3 kg) of refined cane and beet sugar.[41][42] This decrease in domestic consumption of HFCS resulted in a push in exporting of the product. In 2014, exports of HFCS were valued at $436 million, a decrease of 21% in one year, with Mexico receiving about 75% of the export volume.[6]

In 2010, the Corn Refiners Association petitioned the FDA to call HFCS "corn sugar," but the petition was denied.[43]

Vietnam

[edit]90% of Vietnam's HFCS import comes from China and South Korea. Imports would total 89,343 tonnes in 2017.[44] One ton of HFCS was priced at $398 in 2017, while one ton of sugar would cost $702. HFCS has a zero cent import tax and no quota, while sugarcane under quota has a 5% tax, and white and raw sugar not under quota have an 85% and 80% tax.[45] In 2018, the Vietnam Sugarcane and Sugar Association (VSSA) called for government intervention on current tax policies.[44][45] According to the VSSA, sugar companies face tighter lending policies which cause the association's member companies with increased risk of bankruptcy.[46]

Health

[edit]| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,176 kJ (281 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

76 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 76 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 24 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[47] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[48] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nutrition

[edit]HFCS is 76% carbohydrates and 24% water, containing no fat, protein, or micronutrients in significant amounts. In a 100-gram reference amount, it supplies 281 calories, while in one tablespoon of 19 grams, it supplies 53 calories.

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

[edit]The role of fructose in metabolic syndrome has been the subject of controversy, but as of 2022[update], there is no scientific consensus that fructose or HFCS has any impact on cardiometabolic markers when substituted for sucrose.[49][50] A 2014 systematic review found little evidence for an association between HFCS consumption and liver diseases, enzyme levels or fat content.[51]

A 2018 review found that lowering consumption of sugary beverages and fructose products may reduce hepatic fat accumulation, which is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.[52] In 2018, the American Heart Association recommended that people limit total added sugar (including maltose, sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, molasses, cane sugar, corn sweetener, raw sugar, syrup, honey, or fruit juice concentrates) in their diets to nine teaspoons per day for men and six for women.[53]

Safety and manufacturing concerns

[edit]Since 2014, the United States FDA has determined that HFCS is safe (GRAS) as an ingredient for food and beverage manufacturing,[54] and there is no evidence that retail HFCS products differ in safety from those containing alternative nutritive sweeteners. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended that added sugars should be limited in the diet.[4][5]

One consumer concern about HFCS is that processing of corn is more complex than used for common sugar sources, such as fruit juice concentrates or agave nectar, but all sweetener products derived from raw materials involve similar processing steps of pulping, hydrolysis, enzyme treatment, and filtration, among other common steps of sweetener manufacturing from natural sources.[4] In the contemporary process to make HFCS, an "acid-enzyme" step is used in which the corn starch solution is acidified to digest the existing carbohydrates, then enzymes are added to further metabolize the corn starch and convert the resulting sugars to their constituents of fructose and glucose. Analyses published in 2014 showed that HFCS content of fructose was consistent across samples from 80 randomly selected carbonated beverages sweetened with HFCS.[55]

One prior concern in manufacturing was whether HFCS contains reactive carbonyl compounds or advanced glycation end-products evolved during processing.[56] This concern was dismissed, however, with evidence that HFCS poses no dietary risk from these compounds.[4]

As late as 2004, some factories manufacturing HFCS used a chlor-alkali corn processing method which, in cases of applying mercury cell technology for digesting corn raw material, left trace residues of mercury in some batches of HFCS.[57] In a 2009 release,[58] The Corn Refiners Association stated that all factories in the American industry for manufacturing HFCS had used mercury-free processing over several previous years, making the prior report outdated.[57]

Other

[edit]Taste difference

[edit]Most countries, including Mexico, use sucrose, or table sugar, in soft drinks. In the U.S., soft drinks, such as Coca-Cola, are typically made with HFCS 55. HFCS has a sweeter taste than sucrose. Some Americans seek out drinks such as Mexican Coca-Cola in ethnic groceries because they prefer the taste over that of HFCS-sweetened Coca-Cola.[59][60] Kosher Coca-Cola, sold in the U.S. around the Jewish holiday of Passover, also uses sucrose rather than HFCS.[61]

Beekeeping

[edit]In apiculture in the United States, HFCS is a honey substitute for some managed honey bee colonies during times when nectar is in low supply.[62][63] However, when HFCS is heated to about 45 °C (113 °F), hydroxymethylfurfural, which is toxic to bees, can form from the breakdown of fructose.[64][65] Although some researchers cite honey substitution with HFCS as one factor among many for colony collapse disorder, there is no evidence that HFCS is the only cause.[62][63][66] Compared to hive honey, both HFCS and sucrose caused signs of malnutrition in bees fed with them, apparent in the expression of genes involved in protein metabolism and other processes affecting honey bee health.[63]

Public relations

[edit]There are various public relations concerns with HFCS, including how HFCS products are advertised and labeled as "natural." As a consequence, several companies reverted to manufacturing with sucrose (table sugar) from products that had previously been made with HFCS.[67] In 2010, the Corn Refiners Association applied to allow HFCS to be renamed "corn sugar," but that petition was rejected by the FDA in 2012.[68]

In August 2016, in a move to please consumers with health concerns, McDonald's announced that it would be replacing all HFCS in their buns with sucrose (table sugar) and would remove preservatives and other artificial additives from its menu items.[69] Marion Gross, senior vice president of McDonald's stated, "We know that they [consumers] don't feel good about high-fructose corn syrup so we're giving them what they're looking for instead."[69] Over the early 21st century, other companies such as Yoplait, Gatorade, and Hershey's also phased out HFCS, replacing it with conventional sugar because consumers perceived sugar to be healthier.[70][71] Companies such as PepsiCo and Heinz have also released products that use sugar in lieu of HFCS, although they still sell HFCS-sweetened products.[67][70]

History

[edit]Commercial production of HFCS began in 1964.[3]: 17 In the late 1950s, scientists at Clinton Corn Processing Company of Clinton, Iowa, tried to turn glucose from corn starch into fructose, but the process they used was not scalable.[3]: 17 [72] In 1965–1970, Yoshiyuki Takasaki, at the Japanese National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology developed a heat-stable xylose isomerase enzyme from yeast. In 1967, the Clinton Corn Processing Company obtained an exclusive license to manufacture glucose isomerase derived from Streptomyces bacteria and began shipping an early version of HFCS in February 1967.[3]: 140 In 1983, the FDA accepted HFCS as "generally recognized as safe," and that decision was reaffirmed in 1996.[73][74]

Prior to the development of the worldwide sugar industry, dietary fructose was limited to only a few items. Milk, meats, and most vegetables, the staples of many early diets, have no fructose, and only 5–10% fructose by weight is found in fruits such as grapes, apples, and blueberries. Most traditional dried fruits, however, contain about 50% fructose. From 1970 to 2000, there was a 25% increase in "added sugars" in the U.S.[75] When recognized as a cheaper, more versatile sweetener, HFCS replaced sucrose as the main sweetener of soft drinks in the United States.[8]

Since 1789, the U.S. sugar industry has had trade protection in the form of tariffs on foreign-produced sugar,[76] while subsidies to corn growers cheapen the primary ingredient in HFCS, corn. Accordingly, industrial users looking for cheaper sugar replacements rapidly adopted HFCS in the 1970s.[77][78]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ European Starch Association (10 June 2013). "Factsheet on Glucose Fructose Syrups and Isoglucose".

- ^ "Glucose-fructose syrup: How is it produced?". European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e White, John S. (21 February 2014). "Sucrose, HFCS, and Fructose: History, Manufacture, Composition, Applications, and Production". In Rippe, James M. (ed.). Fructose, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Sucrose and Health. Humana Press (published 2014). ISBN 9781489980779. OL 37192628M.

- ^ a b c d White, J. S. (2009). "Misconceptions about high-fructose corn syrup: Is it uniquely responsible for obesity, reactive dicarbonyl compounds, and advanced glycation endproducts?". Journal of Nutrition. 139 (6): 1219S–1227S. doi:10.3945/jn.108.097998. PMID 19386820.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "High Fructose Corn Syrup: Questions and Answers". US Food and Drug Administration. 4 January 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ a b "U.S. Exports of Corn-Based Products Continue to Climb". Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ (Bray, 2004 & U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Sugar and Sweetener Yearbook series, Tables 50–52)

- ^ a b c d e f g White, John S (1 November 2008). "Straight talk about high-fructose corn syrup: what it is and what it ain't". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (6): 1716S–1721S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.25825b. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 19064536.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (28 April 2009). "Dark sugar: The decline and fall of high-fructose corn syrup". Slate Magazine. Slate.com. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Goran, Michael I.; Ulijaszek, Stanley J.; Ventura, Emily E. (1 January 2013). "High fructose corn syrup and diabetes prevalence: A global perspective". Global Public Health. 8 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1080/17441692.2012.736257. ISSN 1744-1692. PMID 23181629. S2CID 15658896.

- ^ Hanover LM, White JS (1993). "Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58 (suppl 5): 724S–732S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.5.724S. PMID 8213603.

- ^ "5 Things You Need to Know About Maple Syrup". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Advances in Honey Adulteration Detection". Food Safety Magazine. 12 August 1974. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Everstine K, Spink J, Kennedy S (April 2013). "Economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food: common characteristics of EMA incidents". J Food Prot. 76 (4): 723–35. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-399. PMID 23575142.

Because the sugar profile of high-fructose corn syrup is similar to that of honey, high-fructose corn syrup was more difficult to detect until new tests were developed in the 1980s. Honey adulteration has continued to evolve to evade testing methodology, requiring continual updating of testing methods.

- ^ a b Hobbs, Larry (2009). "21. Sweeteners from Starch: Production, Properties and Uses". In BeMiller, James N.; Whistler, Roy L. (eds.). Starch: chemistry and technology (3rd ed.). London: Academic Press/Elsevier. pp. 797–832. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-746275-2.00021-5. ISBN 978-0-12-746275-2.

- ^ Rizkalla, S. W. (2010). "Health implications of fructose consumption: A review of recent data". Nutrition & Metabolism. 7: 82. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-82. PMC 2991323. PMID 21050460.

- ^ "Sugar and Sweeteners: Background". United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Japan Corn Starch Co., Ltd. Releasing the New High-Fructose Corn Syrup, "HFCS 70"!!". www.businesswire.com. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "High Fructose Corn Syrup Market 2019 Industry Research, Share, Trend, Global Industry Size, Price, Future Analysis, Regional Outlook to 2024 Research Report". MarketWatch. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ a b Gu, Hallie; Cruz, Enrico Dela (20 July 2017). "Old foes sugar and corn syrup battle for lucrative Asian market". Reuters. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Glucose-fructose syrup: An ingredient worth knowing" (PDF). Starch EU, Brussels, Belgium. June 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ a b "The end of EU sugar production quotas and its impact on sugar consumption in the EU". Starch EU, Brussels, Belgium. 20 June 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Updated factsheet on glucose fructose syrups, isoglucose and high fructose corn syrup". Starch EU, Brussels, Belgium. 13 July 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Quality Labeling Standard for Processed Foods" (PDF). Punto Focal. 27 October 2006. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Sweetener Policies in Japan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ International Sugar Organization March 2012 Alternative Sweeteners in a High Sugar Price Environment.

- ^ "Japan Trade Agreements Affect US Sweetener Confections" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture Japan. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Table 32-U.S. high fructose corn syrup exports, by destinations, 2000–2015". United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 20 November 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Production Sufficient to Meet U.S. Quota Demand" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. 15 April 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Table 34a-U.S. exports of high fructose corn syrup to Mexico". United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mexicos HFCS imports usage increasing | World-grain.com | 29 April 2011 09:04". www.world-grain.com. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Report of the Agricultural Technical Advisory Committee (ATAC) for Sweeteners and Sweetener Products" (PDF). Office of the United States Trade Representative. 27 September 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Wins Mexico Beverage Tax Dispute". Office of the United States Trade Representative. 3 March 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Philippines drinks makers shun China corn syrup imports to avoid tax". Reuters. 30 January 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "USDA ERS – Background". www.ers.usda.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Sugar and sweeteners". United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ "Understanding High Fructose Corn Syrup". Beverage Institute.

- ^ Daniels, Lee A. (7 November 1984). "Coke, Pepsi to use more corn syrup". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ James Bovard. "Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare". cato.org. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ "Table 52-High fructose corn syrup: estimated number of per capita calories consumed daily, by calendar year". Economic Research Service. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Table 51-Refined cane and beet sugar: estimated number of per capita calories consumed daily, by calendar year". Economic Research Service. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Consumption of Caloric Sweeteners". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Landa, Michael M (30 May 2012). "Response to Petition from Corn Refiners Association to Authorize "Corn Sugar" as an Alternate Common or Usual Name for High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Sugar association seeks help against corn syrup imports". Vietnam News. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b Chanh, Trung (20 August 2018). "VSSA proposes self-defense measure against HFCS". The Saigon Times. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Sugar association seeks help amid bankruptcy fears | DTiNews – Dan Tri International". dtinews.vn. 10 April 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Fattore E, Botta F, Bosetti C (January 2022). "Effect of fructose instead of glucose or sucrose on cardiometabolic markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of isoenergetic intervention trials". Nutrition Reviews (Systematic review). 79 (2): 209–226. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaa077. PMID 33029629.

- ^ Allocca, M; Selmi C (2010). "Emerging nutritional treatments for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". In Preedy VR; Lakshman R; Rajaskanthan RS (eds.). Nutrition, diet therapy, and the liver. CRC Press. pp. 131–146. ISBN 978-1-4200-8549-5.

- ^ Chung, M; Ma, J; Patel, K; Berger, S; Lau, J; Lichtenstein, A. H. (2014). "Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: A systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 100 (3): 833–849. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.086314. PMC 4135494. PMID 25099546.

- ^ Jensen, Thomas; Abdelmalek, Manal F.; Sullivan, Shelby; Nadeau, Kristen J.; Green, Melanie; Roncal, Carlos; Nakagawa, Takahiko; Kuwabara, Masanari; Sato, Yuka; Kang, Duk-Hee; Tolan, Dean R. (May 2018). "Fructose and Sugar: A Major Mediator of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease". Journal of Hepatology. 68 (5): 1063–1075. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.019. ISSN 0168-8278. PMC 5893377. PMID 29408694.

- ^ "Added sugars". American Heart Association. 17 April 2018.

The AHA recommendations focus on all added sugars, without singling out any particular types such as high-fructose corn syrup

- ^ "CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Listing of Specific Substances Affirmed as GRAS. Sec. 184.1866. High fructose corn syrup (amended 1 April 2020)". US Code of Regulations, Food and Drug Administration. 23 August 1996. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ White, J. S.; Hobbs, L. J.; Fernandez, S (2014). "Fructose content and composition of commercial HFCS-sweetened carbonated beverages". International Journal of Obesity. 39 (1): 176–182. doi:10.1038/ijo.2014.73. PMC 4285619. PMID 24798032.

- ^ "Soda Warning? High-fructose Corn Syrup Linked To Diabetes, New Study Suggests". ScienceDaily. 23 August 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b Dufault, Renee (2009). "Mercury from chlor-alkali plants: measured concentrations in food product sugar". Environmental Health. 8 (1): 2. Bibcode:2009EnvHe...8....2D. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-2. PMC 2637263. PMID 19171026.

- ^ "High Fructose Corn Syrup Mercury Study Outdated; Based on Discontinued Technology". The Corn Refiners Association. 26 January 2009. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Louise Chu (9 November 2004). "Is Mexican Coke the real thing?". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007.

- ^ "Mexican Coke a hit in U.S." The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ Dixon, Duffie (9 April 2009). "Kosher Coke 'flying out of the store'". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ a b Mao, W; Schuler, M. A.; Berenbaum, M. R. (2013). "Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (22): 8842–8846. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8842M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303884110. PMC 3670375. PMID 23630255.

- ^ a b c Wheeler, M. M.; Robinson, G. E. (2014). "Diet-dependent gene expression in honey bees: Honey vs. Sucrose or high fructose corn syrup". Scientific Reports. 4: 5726. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4.5726W. doi:10.1038/srep05726. PMC 4103092. PMID 25034029.

- ^ Krainer, S; Brodschneider, R; Vollmann, J; Crailsheim, K; Riessberger-Gallé, U (2016). "Effect of hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) on mortality of artificially reared honey bee larvae (Apis mellifera carnica)". Ecotoxicology. 25 (2): 320–8. Bibcode:2016Ecotx..25..320K. doi:10.1007/s10646-015-1590-x. PMID 26590927. S2CID 207121566.

- ^ Leblanc, B. W.; Eggleston, G; Sammataro, D; Cornett, C; Dufault, R; Deeby, T; St Cyr, E (2009). "Formation of hydroxymethylfurfural in domestic high-fructose corn syrup and its toxicity to the honey bee (Apis mellifera)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (16): 7369–76. Bibcode:2009JAFC...57.7369L. doi:10.1021/jf9014526. PMID 19645504.

- ^ "Colony collapse disorder". US Environmental Protection Agency. 16 September 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b Senapathy, Kavin (28 April 2016). "Pepsi, Coke And Other Soda Companies Want You To Think 'Real' Sugar Is Good For You—It's Not". Forbes. US. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020.

- ^ "FDA rejects industry bid to change name of high fructose corn syrup to "corn sugar"". CBS News. 31 May 2012.

- ^ a b "McDonald's to remove corn syrup from buns, curbs antibiotics in chicken". CNBC. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ a b Zmuda, Natalie (15 March 2010). "Major Brands No Longer Sweet on High-Fructose Corn Syrup". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ "Hershey considers removing high-fructose corn syrup from products in favor of sugar". The Guardian, London, UK. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Marshall R. O.; Kooi E. R. (1957). "Enzymatic Conversion of d-Glucose to d-Fructose". Science. 125 (3249): 648–649. Bibcode:1957Sci...125..648M. doi:10.1126/science.125.3249.648. PMID 13421660.

- ^ "Database of Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Reviews (updated 29 April 2019)". US Food and Drug Administration. 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ High Fructose Corn Syrup: A Guide for Consumers, Policymakers, and the Media (PDF). Grocery Manufacturers Association. 2008. pp. 1–14.

- ^ Leeper H. A.; Jones E. (October 2007). "How bad is fructose?" (PDF). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86 (4): 895–896. doi:10.1093/ajcn/86.4.895. PMID 17921361.

- ^ "U.S. Sugar Policy". SugarCane.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Food without Thought: How U.S. Farm Policy Contributes to Obesity". Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. November 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Corn Production/Value". Allcountries.org. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

External links

[edit] Media related to High-fructose corn syrup at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to High-fructose corn syrup at Wikimedia Commons