Glossotherium

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (February 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Glossotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| G. robustum skeleton at the Natural History Museum, London | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Mylodontidae |

| Subfamily: | †Mylodontinae |

| Tribe: | †Mylodontini |

| Genus: | †Glossotherium Owen 1840 |

| Type species | |

| †Glossotherium robustum Owen, 1840

| |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

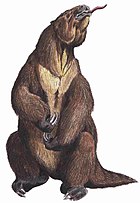

Glossotherium is an extinct genus of large mylodontid ground sloths of the subfamily Mylodontinae. It represents one of the best-known members of the family, along with Mylodon and Paramylodon. Reconstructed animals were between 3 and 4 metres (9.8 and 13.1 ft) long and possibly weighed up to 1,002.6–1,500 kg. The majority of finds of Glossotherium date from the Middle and Upper Pleistocene, around 300,000 to 10,000 years ago, with a few dating older, as far back Pliocene, about 3.3-3 million years ago.[2] The range included large parts of South America, east of the Andes roughly from latitude 20 to 40 degrees south, leaving out the Amazon Basin in the north. In western South America, finds are also documented north of the equator. The animals largely inhabited the open landscapes of the Pampas and northern savanna regions.

Like other mylodonts, Glossotherium was adapted to a more or less grassy diet, as indicated by the broad snout and the design of the teeth. This view is confirmed by isotopic analysis. The anatomical structure of their locomotor system suggests quadrupedal locomotion, but they were also capable of changing to a bipedal stance. The particularly strong construction of the forelimbs is remarkable, leading to the assumption that Glossotherium burrowed underground. Large fossil burrows with corresponding scratch marks support this assumption, possibly making it the largest known burrowing mammal ever. The structure of the auditory system shows that Glossotherium could perceive frequencies in infrasound and probably produce them with the help of its voluminous nasal cavity.

The research history of the genus is very complex. The first description was made in 1840 by Richard Owen. However, he discarded the genus name just two years later. Subsequently, this led to persistent confusion and equation with Mylodon and other forms, which was not resolved until the 1920s. Especially during the 20th century, Glossotherium was considered identical to the North American Paramylodon. It was not until the 1990s that it became widely accepted that the two genera are independent.

Description

[edit]

Glossotherium belongs to the Mylodontidae, in which it is further subcategorized into the Mylodontinae, characterized both by the loss of the entepicondylar foramen of the distal humerus and anteriorly broad snouts.[3] Mylodontinae has three famous genera: Mylodon, Paramylodon and Glossotherium. The latter three have frequently been confused for each other in scientific literature,[3] though it is likely Paramylodon and Glossotherium share a more recent common ancestor than with any other mylodontid.[4] Paramylodon is typically larger than Glossotherium, even though there is overlap in their size ranges, and Glossotherium is generally wider and more robust with a diagnostic increased amount of lateral flare at the predental spout.[4]

Glossotherium robustum was endemic to South America and weighed about 1,002.6 to 1,500 kilograms (2,210 to 3,310 lb).[5][6][7] Pleistocene records indicate that it was widely distributed between 20°S and 40°S, with a range spanning across Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela and Paraguay.[8]

Dentition

[edit]Sloths have an ever-growing adult dentition. They lack deciduous dentition and have a reduction in tooth number. Sloth teeth also lack the enamel and cuspation pattern generally present in other mammals. Their tooth forms are oval, subrectangular, or elongate irregular ovoid with chisel-shaped "caniniform" teeth

anteriorly and "molariform" cheek teeth. Glossotherium has a layer of cementum surrounding all molariform cheek teeth with some traces on caniniform teeth. Cheek teeth in Glossotherium are larger, have more complex shapes, and retain more of the cementum layer around all sides of each tooth than the Shasta ground sloth, Nothrotheriops shastensis, and tree sloths.[3]

Discovery

[edit]

Fossils of this animal have been found in South America.[9] It is closely related to Paramylodon of North America, whose specimens have often been confused with it and assigned to Glossotherium, which in turn was initially assigned to Mylodon. The earliest Glossotherium specimens are known from the Pliocene of South America and are represented by the species, G. chapadmalense. All specimens of Pleistocene age are typically lumped into G. robustum and a few other questionable species. Further research is needed at the species level.

Palaeobiology

[edit]Due to its size and strength, Glossotherium would have had few natural enemies apart from the South American short-faced bear Arctotherium and sabre-toothed cats such as Smilodon. It is believed to have died out in the Pleistocene (1.8 million to 12,000 years ago).[citation needed] The most recent reported date is about 8,700 years BP.[10]

Diet

[edit]

Details of Glossotherium's diet are unclear since no dung deposits are available for analysis. However, based on dental evidence, Glossotherium was likely more suited to grazing, though it was also probably less efficient at ingesting grasses since its dental apparatus was more suited to shearing, which would have been too ineffective at processing plant materials down to an ingestible size to obtain adequate nutritive value. More recent tree sloths have a very slow rate of passage of food through the gut and it is likely that Glossotherium did as well. With a likely low metabolic rate, a large body size, a consequently reduced energy requirement for its weight, and an extraordinarily large gut that likely had a foregut fermentation site, Glossotherium could probably survive better on foods of lower nutritional value than other sloths could. Though it is likely Glossotherium primarily ate grasses, it also probably ate a variety of foliage as well and would be better considered a "browser-grazer" than simply a grazer.[3] Evidence from Santa Elina suggests that the niche breadth of G. phoenesis decreased from the Last Glacial Maximum onward.[11]

Hearing

[edit]Glossotherium had large ear ossicles, similar to those in elephants, which imply the loss of hearing acuity of higher frequencies, further implying an advantage for sensing low frequency sounds, infrasound, or bone-conducting seismic waves.[7] Low frequency sound is useful for long range communication and it is possible that ground sloths used low frequency communication in much the same way that it is utilized by elephants. Sloths may have used low frequency sounds for communication in mating calls or other social interactions, or for long-range sound sensing as in predator-prey interactions or weather forecasting.[7] Another possible explanation for hearing in low frequencies may be due to fossorial habits: low hearing frequencies coupled with a short interaural distance suggest that Glossotherium probably had very poor sound localization. This indicates evidence of an underground lifestyle since loss of high frequency hearing is common to fossorial mammals.[12] Glossotherium's huge nostrils were likely effective for sound emission, with expanded nares possibly related to emission of low frequency sounds up to 600 Hz.[7]

Distribution

[edit]Fossils of Glossotherium have been found in:[13]

- Luján and Agua Blanca Formations, Argentina

- Charana and Tarija Formations, Bolivia

- Japones Cave, Lagoa Santa and Lage Grande, Brazil

- Santa Elena Peninsula, Ecuador

- General Bruguer/Riacho Negro, Paraguay

- Talara tar seeps, Peru

- Sopas Formation, Uruguay

- Taima-Taima, Venezuela

References

[edit]- ^ Boscaini, Alberto; Toledo, Néstor; Pérez, Leandro M.; Taglioretti, Matías L.; McAfee, Robert K. (2022-11-01). "New well-preserved materials of Glossotherium chapadmalense (Xenarthra, Mylodontidae) from the Pliocene of Argentina shed light on the origin and evolution of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 42 (2): e2128688. Bibcode:2022JVPal..42E8688B. doi:10.1080/02724634.2022.2128688. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 253286158.

- ^ Boscaini, Alberto; Toledo, Néstor; Pérez, Leandro M.; Taglioretti, Matías L.; Mcafee, Robert K. (2022-08-31). "New well-preserved materials of Glossotherium chapadmalense (Xenarthra, Mylodontidae) from the Pliocene of Argentina shed light on the origin and evolution of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 42 (2): e2128688. Bibcode:2022JVPal..42E8688B. doi:10.1080/02724634.2022.2128688. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 253286158.

- ^ a b c d Naples, V. (1989). "The feeding mechanism in the Pleistocene ground sloth, Glossotherium". Contributions in Science. 415: 1–23. doi:10.5962/p.226818. S2CID 134669706.

- ^ a b McAfee, R. (2009). "Reassessment of the cranial characters of Glossotherium and Paramylodon (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Mylodontidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 155 (4): 885–903. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00468.x.

- ^ http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/16838?show=full (in Spanish)

- ^ Fariña RA, Czerwonogora A, di Giacomo M (March 2014). "Splendid oddness: revisiting the curious trophic relationships of South American Pleistocene mammals and their abundance". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 86 (1): 311–31. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420120010. PMID 24676170.

- ^ a b c d Blanco, R. (2008). "Estimation of hearing capabilities of Pleistocene ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from middle-ear anatomy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28: 274–276. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[274:eohcop]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86266809.

- ^ Pitana, V. (2013). "Cranial and dental studies of Glossotherium robustum (Owen, 1842) (Xenarthra: Pilosa: Mylodontidae) from the Pleistocene of southern Brazil". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 37 (2): 147–162. Bibcode:2013Alch...37..147P. doi:10.1080/03115518.2012.717463. S2CID 128699768.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Glossotherium".

- ^ Turvey, Sam (2009). Holocene extinctions. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-953509-5.

- ^ Pansani, Thais Rabito; Dantas, Mário André Trindade; Asevedo, Lidiane; Cherkinsky, Alexander; Vialou, Denis; Vialou, Águeda Vilhena; Pacheco, Mírian Liza Alves Forancelli (10 July 2023). "Radiocarbon dating and isotopic palaeoecology of Glossotherium phoenesis from the Late Pleistocene of the Santa Elina rock shelter, Central Brazil". Journal of Quaternary Science. doi:10.1002/jqs.3553. ISSN 0267-8179. Retrieved 9 March 2024 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Blanco, R. (2012). "Fossil evidence of frequency range of hearing independent of body size in South American Pleistocene ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (8): 549–554. Bibcode:2012CRPal..11..549B. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.07.003.

- ^ Glossotherium at Fossilworks.org

Further reading

[edit]- C. M. Deschamps and A. M. Borromei. 1992. La fauna de vertebrados pleistocénicos del Bajo San José (provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina). Aspectos paleoambientales. Ameghiniana 29(2):177-183

- E. Lindsey and E. Lopez. 2015. Tanque Loma, a new late-Pleistocene megafaunal tar seep locality from southwest Ecuador . Journal of South American Earth Sciences 57:61-82

- C. D. Paula Couto. 1980. Fossil Pleistocene to Sub-Recent Mammals from Northeastern Brazil. I - Edentata Megalonychidae. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencas 52(1):143-151

- F. Pujos and R. Salas. 2004. A systematic reassessment and paleogeographic review of fossil Xenarthra from Peru. Bulletin de l'institut Francais d'Études Andines 33:331-377

- L. O. Salles, C. Cartelle, P. G. Guedes, P. C. Boggiani, A. Janoo and C. A. M. Russo. 2006. Quaternary mammals from Serra do Bodoquena, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Boletim do Museu Nacional 521:1-12

- Prehistoric sloths

- Pliocene xenarthrans

- Pleistocene xenarthrans

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Piacenzian first appearances

- Holocene extinctions

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Pliocene mammals of South America

- Uquian

- Ensenadan

- Lujanian

- Sopas Formation

- Pleistocene Argentina

- Fossils of Argentina

- Pleistocene Bolivia

- Fossils of Bolivia

- Pleistocene Brazil

- Fossils of Brazil

- Pleistocene Chile

- Fossils of Chile

- Pleistocene Colombia

- Fossils of Colombia

- Pleistocene Ecuador

- Fossils of Ecuador

- Pleistocene Paraguay

- Fossils of Paraguay

- Pleistocene Peru

- Fossils of Peru

- Pleistocene Uruguay

- Fossils of Uruguay

- Pleistocene Venezuela

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Fossil taxa described in 1840

- Taxa named by Richard Owen