Discrimination against people with red hair

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Discrimination against people with red hair is the prejudice, stereotyping and dehumanization of people with naturally red hair. In contemporary form, it often involves a cultural discrimination against people with red hair. A number of stereotypes exist about people with red hair, many of which engender harmful or discriminatory treatment towards them.

While discrimination against people with red hair has occurred for thousands of years and in many countries, in modern times it has been described as particularly acute in the United Kingdom, where there have been calls to designate red hair a protected characteristic covered by hate crime legislation.[1]

Background

[edit]Naturally occurring red hair appears in a small minority of humans and is the rarest natural hair color, occurring in 0.6 percent of people.[2] A smaller percentage of humans, approximately 0.17 percent or 13 million, have a combination of red hair and blue eyes.[3]

Red hair is one potential manifestation of a gene mutation in the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R).[4] While red hair most frequently occurs among European peoples, it is also present among persons of Asian descent or Africans with European admixture (though extremely rare).[5] A higher prevalence of the MC1R mutation in Europe may be due to it promoting adaptability to low light environments as it facilitates efficient biosynthesis of Vitamin D among other survival traits such as higher resilience to certain types of pain, and increased levels of adrenaline that accelerates the fight-or-flight response.[6][7][8]

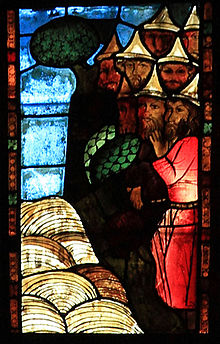

The history of prejudice and discrimination against people with red hair dates back thousands of years.[9] According to The Week, persons with red hair have to deal with "insults ... taunts, and ... hate crimes".[10] Discrimination against people with red hair may be a factor of its relative rareness, as well as cultural attitudes and collective mythology.[11] Judas Iscariot may have had red hair, and some Indo European folklore presents that people with red hair are vampires or transform into vampires after death.[11] The assignment of prejudicial characteristics towards people with red hair, such as a propensity towards violence, may also be a long-lasting association Eurasian peoples had to the hair color resulting from their contact with aggressive and violent Thracian tribes which had a high prevalence of red hair.[12]

Trends and occurrences

[edit]Ancient Egypt

[edit]

In Ancient Egypt, men with red hair may have been used as human sacrifices to the god Osiris due to the belief that his archenemy, Set, had red hair and that those with red hair were, therefore, devotees of Set.[13][14] Though, rulers of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt may have been red haired followers of Set; Ramesses II had red hair and his father's name, Seti I, means "follower of Set".[15]

Australia

[edit]From the 1894 novel Seven Little Australians: "Nell seemed to grow prettier every day. Pip had his hands full with trying to keep her from growing conceited; if brotherly rubs and snubs availed anything, she ought to have been as lowly minded as if she had had red hair and a nose of heavenward bent."

In 2008, the Adelaide Zoo faced criticism after it launched a promotional campaign for its orangutan exhibit in which people with red hair were offered free admission.[16] In promotional communication, the zoo compared people with red hair to the ape species, claimed people with red hair were destined for extinction, and used the pejorative term "ranga" to refer to them.[16] In response to what the zoo characterized as a "negative reaction" to the campaign, it dropped one element that involved photographing people with red hair next to the orangutan exhibit for use in advertising materials.[16]

In 2010, several ads in Australia centered around ridiculing people with red hair.[17] One, a government road safety campaign, suggested that using a mobile phone while driving might cause unwanted side effects such as sexual intercourse between two people with red hair, an occurrence which might result in the offspring also having red hair.[17] Another, for ANZ Bank, featured a character of a bank clerk who was comically rude towards customers.[17]

In 2018, a television advertisement for Carlton & United Breweries Yak Ales was criticized after the Advertising Standards Authority found that it vilified people with red hair by suggesting society should work towards their eradication.[18] Carlton & United ultimately pulled the ad, but declined to apologize for it.[18]

Canada

[edit]In 2009, students with red hair from at least three Canadian schools, were reportedly assaulted by their classmates, with one incident being confirmed by a court verdict. The students were influenced by a Facebook group that promoted so-called "Kick a Ginger Day", and possibly by a 2005 South Park episode.[19]

France

[edit]Until recently, it was not uncommon for people with red hair in France to be called Poil de Judas ("hair of Judas"), a reference to the idea that Judas Iscariot had red hair.[20] However, in 2024, the National Assembly passed a law banning hair-based discrimination, which covers people with red hair as well as those with dreadlocks, Afro hair, blonde hair, curly hair or no hair at all.[21]

Germany

[edit]

In the past, red hair has been wrongly believed to be a characteristic associated exclusively or significantly with Jews, due to the belief that Judas Iscariot had red hair.[22] In medieval Germany, some believed a tribe of Rote Juden, or "Red Jews", inhabited the Caucasus Mountains.[22] According to myth, this was a reclusive tribe of Jews with red hair conspiring with the Antichrist to destroy Christianity.[22] It has been hypothesized that this belief may have originated in the fragment of a social memory of the Khazars who, according to some sources, had a high prevalence of red hair and blue eyes.[23]

In some instances, women with red hair were often presumed to be witches and subject to punitive violence.[20]

United Kingdom

[edit]According to some observers, red haired people in the United Kingdom face particularly "aggressive" discrimination due to systemic "prejudice ... related to centuries-old matters of imperialism, religious bigotry and war".[24] According to TRT World, the UK is "arguably the nation most hostile to this hair colour" despite red hair having the highest incidence in that country.[25] The UK's Anti-Bullying Alliance has called for red hair to be listed as a protected characteristic, which would result in the targeting of people with red hair for criminal acts classified as a hate crime.[25] Some have said that people with red hair are abused by those who would prefer to abuse racial minorities but feel restrained by hate crimes legislation and, therefore, target classes of people not protected by law.[26]

In a 2013 article in New Statesman, columnist Nelson Jones chronicled several anecdotes of people with red hair who had been physically assaulted that year in the United Kingdom due to their hair color, including at least one stabbing.[1] A 2014 study found that more than 90 percent of men in the UK with red hair had been the target of bullying due exclusively to their hair color.[27] In addition, the study found, approximately 61 percent of males and 47 percent of females with red hair reported encountering "some kind of discrimination in the past" as a result of their hair color.[27]

According to Lily Cole, who has red hair, being bullied as a child for red hair in the UK was "not dissimilar" to experiencing racial abuse.[28] Prince Harry and David Kitson have reported being abused as a result of their hair color.[29] The head of one children's charity reported that levels of abuse in the UK were significant and said there was "nothing like this in the U.S."[29]

In 2015, a person with red hair was convicted of terrorist offenses over a plot to assassinate Prince Charles and Prince William in order to ensure Prince Harry, who has red hair, would become King of the United Kingdom.[30] The man attributed his genetic supremacist views towards childhood bullying to which he'd been subjected over his hair color.[30]

In 2022, Sheffield-based human rights advocate Chrissy Meleady called for more protection for red-haired children, noting some bullying incidents, including a teaching assistant being fired for making fun of a red-haired student.[31]

United States

[edit]The television program South Park has dealt with the topic of discrimination against people with red hair, most notably in the 2005 episode "Ginger Kids". According to anecdotal reports, children with red hair are regularly assaulted on the so-called "Kick a Ginger Day" supposedly inspired by the episode.[citation needed] In 2015, police in Massachusetts investigated a conspiracy among students who attacked other students with red hair on the date.[32]

Cryos International, one of the world's largest sperm banks, said in 2011 that they had too many sperm doses from red-haired individuals, but agency director Ole Schou said that they "have nothing against red-haired donors".[33]

In some cases, discrimination can occur in the form of preferencing people with red hair over those without red hair. A 2014 study found that 30 percent of television commercials during primetime viewing hours in the United States prominently featured someone with red hair with, at one point, CBS showing a person with red hair once every 106 seconds, numbers not accurately reflective of the actual population of persons with the hair color.[7] Andrew Rohm, professor of marketing at Loyola Marymount University, attributed the prevalence of red hair in television advertising as an attempt by companies to capture viewer attention by showing people with what they perceived to be unusual or exotic physical characteristics.[34]

The casting of Halle Bailey, who does not have natural red hair, to perform the role of Ariel in The Little Mermaid, a remake of the 1989 film where the protagonist does, was criticized by some people as the character was "a wonderful role model for young ginger girls, and this casting is a loss for them", however, due to the concurrent backlash regarding Bailey's race (Bailey is not white like Ariel in the 1989 film), such criticisms have faced accusations of racism.[35]

Stereotypes

[edit]Stereotypes can contribute to hostility towards a group, engender toxic prejudices, and are often used to justify discrimination and oppression. The propagation of stereotypes results, according to linguist Karen Stollznow, in those with red hair frequently having "low self-esteem ... [experiencing] insecurity, and ... [feeling] a profound sense of being not only different from other people but also inferior".[20]

Personality stereotypes

[edit]Stereotypes about people with red hair include the ideas that they are in league with Satanic forces, or of Irish ancestry, both of which are not supported by evidence.[20]

In some areas, people with red hair may be stereotyped as more "competent" than persons with other hair colors, which may manifest in the form of a reverse discriminatory selection bias in which persons with red hair are placed into leadership positions over other individuals at atypically high rates.[36] A study in the UK found that the number of CEOs of top companies with red hair was four times higher than the percentage of persons with red hair in the general population.[36]

Deviance, temper, and violence

[edit]Other stereotypes include that red-haired persons have a propensity to violence or are short-tempered, which are not directly supported by scientific evidence, though some research suggests they produce higher levels of adrenaline which accelerates the fight-or-flight response.[20][37]

A 1946 study by Hans von Hentig published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology observed that there was a high prevalence of red hair among high-profile criminals in the Old West and that "the number of redheaded men among the noted outlaws surpassed their rate in the normal population". Von Hentig, however, attributed this not to a numerically higher incidence of crime among red haired persons but because "of their striking appearance, they might have been remembered rather than ordinary men who killed and were killed."[38]

In art, red-haired persons have been associated with negative qualities like betrayal, falsity, vileness, rebellion and lust. In fact, red hair is a badly looked-upon characteristic according to artists such as Francisco Salzillo (who represents Judas in Last Supper as such), Francisco de Quevedo and Dante Alighieri.[39]

Sexual stereotypes

[edit]Red-haired men have been stereotyped as being well endowed, and both men and women with red hair have been stereotyped as sexually absent or having no libidos.[36] Actually, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his fellow Pre-Raphaelite Brothers have portrayed red-haired people as sensual, erotical and singular.[39]

Physiological differences

[edit]Studies have shown that people with red hair, which is due to the MC1R genetic mutation, have several small physiological differences to others. These include: a generally higher pain tolerance; a more effective response (i.e. at lower doses) to opiate medication;[40] experiencing temperature changes faster and with greater intensity; biosynthesizing Vitamin D more efficiently;[41] a higher risk of melanoma (because the gene with the MC1R mutation does not bind to the PTEN gene) that can be somewhat mitigated by limiting sun exposure;[41] a significantly higher risk of developing Parkinson's disease; in men, a significantly lower risk of prostate cancer;[42] [41] and, in women, a higher prevalence of endometriosis.

Terminology

[edit]Slurs and derogatory terms

[edit]The term "ginger" is considered by some to be pejorative or offensive, with some considering it only acceptable when used by a person with red hair to refer to themselves or others with red hair.[20][24][43][44] The use of the term to refer to persons with red hair may be a reference to the spicy ginger root, an amplification of the stereotype that persons with red hair have abrupt tempers or are prone to violence.[45][46]

The phrase "redheaded stepchild" is a term used, mainly in the United States, to describe a "person or thing that is neglected, unwanted, or mistreated".[47] Using "Red" as a nickname to refer to a person with red hair has been described as overly familiar and potentially offensive.[20] The "white-skinned other" is considered a prejudicial term to refer to Caucasians with red hair.[20]

"Ranga" is a slang term used in New Zealand and Australia to refer to a person with red hair and is an abbreviation of "orangutan", a primate.[48] It is considered an insult.[49] Andrew Rochford has called for Australians and New Zealanders to stop using it.[50]

Non-derogatory terms

[edit]According to the Associated Press Stylebook, "red-haired, redhead and redheaded are all acceptable for a person with red hair."[51] Some people with red hair prefer the term auburn to describe their hair color.[20] American author Mark Twain, who had red hair, said that auburn is typically a color descriptor used for persons with red hair of higher social class.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Jones, Nelson (January 10, 2013). "Should ginger-bashing be considered a hate crime?". New Statesman. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Bramhill, Nick (March 20, 2017). "Discrimination against redheads very real, says author". Irish Central. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Milbrand, Lisa (May 20, 2020). "This Is the Rarest Hair and Eye Color Combination in Humans". Reader's Digest. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Zorina-Lichtenwalter, Katerina; Lichtenwalter, Ryan N; Zaykin, Dima V; Parisien, Marc; Gravel, Simon; Bortsov, Andrey; Diatchenko, Luda (June 15, 2019). "A study in scarlet: MC1R as the main predictor of red hair and exemplar of the flip-flop effect". Human Molecular Genetics. 28 (12): 2093–2106. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddz018. ISSN 0964-6906. PMC 6548228. PMID 30657907.

- ^ Culzac, Natasha (August 24, 2015). "Documenting Gingers of Color". Vice. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Roider, Elisabeth M. (January 18, 2017). "Red hair, light skin, and UV-independent risk for melanoma development in humans". JAMA Dermatol. 152 (7): 751–753. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0524. PMC 5241673. PMID 27050924.

- ^ a b "Science Confirms Redheads are Equipped with Some Rare Genetic Superpowers". GQ. March 12, 2019. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Houston, Muris (September 22, 2015). "Medical Matters: Truths among those redhead myths". Irish Times. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Bianchi, Mike (January 22, 2011). "Is there a bias against redheads in football?". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "The science behind anti-redhead prejudice". The Week. January 8, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood. p. 152. ISBN 0313331456.

- ^ a b Scutts, Joanna (June 12, 2015). "Red hair: a blessing or a curse?". Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 14, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Summers, Montague (2020). The Vampire – His Kith and Kin. Read Books. p. 153. ISBN 978-1528788922.

- ^ Lowe, Scott (2016). Hair. Bloomsbury. p. 108. ISBN 9781628922219.

- ^ Brier, Egyptian Mummies (1994), pp. 200–01.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Patrick (September 28, 2008). "Adelaide Zoo drops its Ranga campaign". The Advertiser. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Jim (June 29, 2010). "Better Red Than Dead? Advertising Complaints Panel Rules "Red Hair Is Not a Disability"". CBS News. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Castrodale, Jelisa (March 21, 2018). "Beer Company Pulls Campaign that Encourages Discrimination Against Redheads". Vice. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ "Judge slams 'vulgar' South Park for 'Kick a Ginger Day' attacks". CBC. May 8, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stollznow, Karen (April 24, 2021). "An Examination of Stereotypes About Hair Color". Psychology Today. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "Afro, dreadlocks, cheveux roux : l'Assemblée nationale vote un texte contre la "discrimination capillaire" au travail" [Afro hair, dreadlocks, red hair: The National Assembly votes a text against "hair-based discrimination" in the workplace]. France Bleu (in French). 2024-03-28. Retrieved 2024-07-16.

- ^ a b c Connelly, Irene Katz (November 5, 2019). "On National Redhead Day, Explore the History of Ginger Jews". The Forward. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Redheaded Warrior Jews". The Forward. August 12, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Fogg, Ally (January 15, 2013). "Gingerism is real, but not all prejudices are equal to one another". The Guardian. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Mahmud, Nafees (November 12, 2020). "What lies beneath the stigmatisation of redheads in the UK?". TRT World. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Rohrer, Finlo (June 6, 2007). "Is gingerism as bad as racism?". BBC News. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Redheads 'easy targets for bullies', claims researcher". BBC News. August 20, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Young, Sarah (April 17, 2020). "Model Lily Cole Says Being Bullied for Red Hair is Not Dissimilar from Racial Abuse". The Independent. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Prince Harry a Victim of Gingerism". Calgary Herald. July 13, 2007.

- ^ a b Cheston, Paul (September 22, 2015). "Neo-nazi who dreamt of killing Prince Charles after being bullied over ginger hair is found guilty in terrorism trial". The Standard. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Ghazali, Rahmah (January 11, 2022). "Sheffield human rights advocate calls for more protection for children with red hair". Sheffield Star. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Hanna, Laurie (November 26, 2015). "Massachusetts middle school students organize South Park-inspired 'Kick A Ginger' day, may face police investigation". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Hayes Taylor, Kimberly (September 22, 2011). "Sperm bank: Redheads not wanted". NBC News. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Wagstaff, Keith (August 10, 2014). "What's up with all the redheads in TV ads?". TODAY. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Wilkinson, Sophie (July 5, 2019). "As a ginger, I'm calling out the racist backlash against The Little Mermaid". The Guardian. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c Persaud, Raj (November 25, 2012). "Hair Colour and Attraction - Is the Latest Psychological Research Bad News for Redheads?". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Best, Amy (1997). "Ugly Duckling to Swan: Labeling Theory and the Stigmatization of Red Hair". Symbolic Interaction. 20 (4): 365–384. doi:10.1525/si.1997.20.4.365.

- ^ von Hentig, Hans (1947). "Redhead and Outlaw: A Study in Criminal Anthropology". Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 1 (1).

- ^ a b Guerra Tapia, Aurora (2013) [12 October 2013]. "Pelirrojos y prerrafaelitas" [The Red-haired and the Pre-Raphaelites]. Más dermatología (in Spanish) (19). Madrid: Editorial Glosa: 28–29. ISSN 1887-5181. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Dialnet (bibliographic database).

- ^ Brown, Noah (April 2, 2021). "Research reveals why redheads may have different pain thresholds". Massachusetts General Hospital.

- ^ a b c Olson, Samantha (August 18, 2015). "8 Ways Having Red Hair Affects A Person's Health, From Pain To Sex". Medical Daily. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Weinstein, Stephanie J.; Virtamo, Jarmo; Albanes, Demetrius (2013). "Pigmentation-related phenotypes and risk of prostate cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 109 (3): 747–750. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.385. ISSN 0007-0920. PMC 3738118. PMID 23860522.

- ^ McAuliffe, Nora-Ide (July 24, 2015). "Is calling redheads 'gingers' an insult or not?". Irish Times. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Harris, Malcolm (July 13, 2014). "Don't call me ginger". Al Jazeera. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Emma (June 14, 2014). "Ginger and Redhead Mean the Same Thing and Should Be Used Interchangeably". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ "Is Life Rosier For Redheads?". WBUR-FM. July 16, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "red-headed stepchild". Lexico. University of Oxford. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Ranga, bogan and mugachino among new words added to Australian dictionary". BBC News. August 24, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "RANGA: Redheads unite to fight bigotry and ridicule". ABC. February 6, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Rebecca (March 22, 2017). "Dr Andrew Rochford slams bullies for calling his 10-year-old son Archie a 'ranga'". news.com.au. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "AP Style tip: red-haired, redhead and redheaded are all acceptable for a person with red hair". Twitter. @APStylebook. Retrieved November 19, 2021.