Gil Scott-Heron

Gil Scott-Heron | |

|---|---|

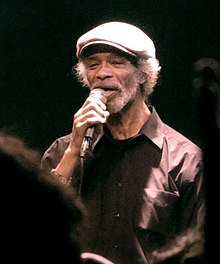

Scott-Heron performing at the Göta Källare nightclub in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2010 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Gilbert Scott-Heron |

| Born | April 1, 1949 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Origin | New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 27, 2011 (aged 62) New York City, U.S.[1] |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1969–2011 |

| Labels | |

| Parent(s) | Bobbie Scott and Gil Heron |

Gilbert Scott-Heron (April 1, 1949 – May 27, 2011)[8] was an American jazz poet, singer,[3] musician, and author known for his work as a spoken-word performer in the 1970s and 1980s. His collaborative efforts with musician Brian Jackson fused jazz, blues, and soul with lyrics relative to social and political issues of the time, delivered in both rapping and melismatic vocal styles. He referred to himself as a "bluesologist",[9] his own term for "a scientist who is concerned with the origin of the blues".[note 1][10] His poem "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", delivered over a jazz-soul beat, is considered a major influence on hip hop music.[11]

Scott-Heron's music, particularly on the albums Pieces of a Man and Winter in America during the early 1970s, influenced and foreshadowed later African-American music genres, including hip hop and neo soul. His recording work received much critical acclaim, especially for "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised".[12] AllMusic's John Bush called him "one of the most important progenitors of rap music", stating that "his aggressive, no-nonsense street poetry inspired a legion of intelligent rappers while his engaging songwriting skills placed him square in the R&B charts later in his career."[6]

Scott-Heron remained active until his death, and in 2010 released his first new album in 16 years, titled I'm New Here. A memoir he had been working on for years up to the time of his death, The Last Holiday, was published posthumously in January 2012.[13][14] Scott-Heron received a posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012. He also is included in the exhibits at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) that officially opened on September 24, 2016, on the National Mall, and in an NMAAHC publication, Dream a World Anew.[15] In 2021, Scott-Heron was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as a recipient of the Early Influence Award.[16]

Early years

[edit]Gil Scott-Heron was born in Chicago.[9] His mother, Bobbie Scott, born in Mississippi,[17] was an opera singer who performed with the Oratorio Society of New York. His father, Gil Heron, nicknamed "The Black Arrow", was a Jamaican footballer who in the 1950s became the first black man to play for Celtic F.C. in Glasgow, Scotland.[18] Gil's parents separated in his early childhood[19] and he was sent to live with his maternal grandmother, Lillie Scott, in Jackson, Tennessee.[20][21] When Scott-Heron was 12 years old, his grandmother died and he returned to live with his mother in The Bronx in New York City. He enrolled at DeWitt Clinton High School[19] but later transferred to The Fieldston School,[9] after impressing the head of the English department with some of his writings and earning a full scholarship.[19] As one of five Black students at the prestigious school, Scott-Heron was faced with alienation and a significant socioeconomic gap. During his admissions interview at Fieldston, an administrator asked him: "'How would you feel if you see one of your classmates go by in a limousine while you're walking up the hill from the subway?' And [he] said, 'Same way as you. Y'all can't afford no limousine. How do you feel?'"[22] This type of intractable boldness would become a hallmark of Scott-Heron's later recordings.

After completing his secondary education, Scott-Heron decided to attend Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania because Langston Hughes (his most important literary influence) was an alumnus. It was here that Scott-Heron met Brian Jackson, with whom he formed the band Black & Blues. After about two years at Lincoln, Scott-Heron took a year off to write the novels The Vulture and The Nigger Factory.[23] Scott-Heron was very heavily influenced by the Black Arts Movement (BAM). The Last Poets, a group associated with the Black Arts Movement, performed at Lincoln in 1969 and Abiodun Oyewole of that Harlem group said Scott-Heron asked him after the performance, "Listen, can I start a group like you guys?"[19] Scott-Heron returned to New York City, settling in Chelsea, Manhattan. The Vulture was published by the World Publishing Company in 1970 to positive reviews.

Although Scott-Heron never completed his undergraduate degree, he was admitted to the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University, where he received an M.A. in creative writing in 1972. His master's thesis was titled Circle of Stone.[24] Beginning in 1972, Scott-Heron taught literature and creative writing for several years as a full-time lecturer at University of the District of Columbia (then known as Federal City College) in Washington, D.C., while maintaining his music career.[25]

Recording career

[edit]Scott-Heron began his recording career with the LP Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970. Bob Thiele of Flying Dutchman Records produced the album, and Scott-Heron was accompanied by Eddie Knowles and Charlie Saunders on conga and David Barnes on percussion and vocals. The album's 14 tracks dealt with themes such as the superficiality of television and mass consumerism, the hypocrisy of some would-be black revolutionaries, and white middle-class ignorance of the difficulties faced by inner-city residents. The album also included the spoken-word poem "Whitey on the Moon". In the liner notes, Scott-Heron acknowledged as influences Richie Havens, John Coltrane, Otis Redding, Jose Feliciano, Billie Holiday, Langston Hughes, Malcolm X, Huey Newton, Nina Simone, and long-time collaborator Brian Jackson.

Scott-Heron's 1971 album Pieces of a Man used more conventional song structures than the loose, spoken-word feel of Small Talk. He was joined by Jackson, Johnny Pate as conductor, Ron Carter on bass and bass guitar, drummer Bernard "Pretty" Purdie, Burt Jones playing electric guitar, and Hubert Laws on flute and saxophone, with Thiele producing again. Scott-Heron's third album, Free Will, was released in 1972. Jackson, Purdie, Laws, Knowles, and Saunders all returned to play on Free Will and were joined by Jerry Jemmott playing bass, David Spinozza on guitar, and Horace Ott (arranger and conductor). Carter later said about Scott-Heron's voice: "He wasn't a great singer, but, with that voice, if he had whispered it would have been dynamic. It was a voice like you would have for Shakespeare."[19]

In 1974, he recorded another collaboration with Brian Jackson, Winter in America, with Bob Adams on drums and Danny Bowens on bass. Winter in America has been regarded by many critics as the two musicians' most artistic effort.[26][27] The following year, Scott-Heron and Jackson released Midnight Band: The First Minute of a New Day. In 1975, he released the single "Johannesburg", a rallying cry for the end of apartheid in South Africa. The song would be re-issued, in 12"-single form, together with "Waiting for the Axe to Fall" and "B-movie" in 1983.

A live album, It's Your World, followed in 1976 and a recording of spoken poetry, The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron, was released in 1978.[28] Another success followed with the hit single "Angel Dust", which he recorded as a single with producer Malcolm Cecil. "Angel Dust" peaked at No. 15 on the R&B charts in 1978.

In 1979, Scott-Heron played at the No Nukes concerts at Madison Square Garden. The concerts were organized by Musicians United for Safe Energy to protest the use of nuclear energy following the Three Mile Island accident. Scott-Heron's song "We Almost Lost Detroit" was included in the No Nukes album of concert highlights. It alluded to a previous nuclear power plant accident and was also the title of a book by John G. Fuller. Scott-Heron was a frequent critic of President Ronald Reagan and his conservative policies.[29]

Scott-Heron recorded and released four albums during the 1980s: 1980 and Real Eyes (1980), Reflections (1981) and Moving Target (1982). In February 1982, Ron Holloway joined the ensemble to play tenor saxophone. He toured extensively with Scott-Heron and contributed to his next album, Moving Target the same year. His tenor accompaniment is a prominent feature of the songs "Fast Lane" and "Black History/The World". Holloway continued with Scott-Heron until the summer of 1989, when he left to join Dizzy Gillespie. Several years later, Scott-Heron would make cameo appearances on two of Ron Holloway's CDs: Scorcher (1996) and Groove Update (1998), both on the Fantasy/Milestone label.[30]

Scott-Heron was dropped by Arista Records in 1985 and quit recording, though he continued to tour. The same year, he helped compose and sang "Let Me See Your I.D." on the Artists United Against Apartheid album Sun City, containing the famous line: "The first time I heard there was trouble in the Middle East, I thought they were talking about Pittsburgh." The song compares racial tensions in the U.S. with those in apartheid-era South Africa, implying that the U.S. was not too far ahead in race relations. In 1993, he signed to TVT Records and released Spirits, an album that included the seminal track "'Message to the Messengers". The first track on the album criticized the rap artists of the day. Scott-Heron is known in many circles as "the Godfather of rap"[31][32] and is widely considered to be one of the genre's founding fathers. Given the political consciousness that lies at the foundation of his work, he can also be called a founder of political rap. "Message to the Messengers" was a plea for the new generation of rappers to speak for change rather than perpetuate the current social situation, and to be more articulate and artistic. Regarding hip hop music in the 1990s, he said in an interview:

They need to study music. I played in several bands before I began my career as a poet. There's a big difference between putting words over some music, and blending those same words into the music. There's not a lot of humor. They use a lot of slang and colloquialisms, and you don't really see inside the person. Instead, you just get a lot of posturing.[33]

— Gil Scott-Heron

Later years

[edit]Prison terms and more performing

[edit]

In 2001, Scott-Heron was sentenced to one to three years imprisonment in a New York State prison for possession of cocaine.[34] While out of jail in 2002, he appeared on the Blazing Arrow album by Blackalicious.[35] He was released on parole in 2003, the year BBC TV broadcast the documentary Gil Scott-Heron: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. Scott-Heron was arrested for possession of a crack pipe during the editing of the film in October 2003 and received a six-month prison sentence.[36]

On July 5, 2006, Scott-Heron was sentenced to two to four years in a New York State prison for violating a plea deal on a drug-possession charge by leaving a drug rehabilitation center. He claimed that he left because the clinic refused to supply him with HIV medication. This story led to the presumption that the artist was HIV positive, subsequently confirmed in a 2008 interview.[37][38][39] Originally sentenced to serve until July 13, 2009, he was paroled on May 23, 2007.[40]

After his release, Scott-Heron began performing live again, starting with a show at SOB's restaurant and nightclub in New York on September 13, 2007. On stage, he stated that he and his musicians were working on a new album and that he had resumed writing a book titled The Last Holiday, previously on long-term hiatus, about Stevie Wonder and his successful attempt to have the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. declared a federally recognized holiday in the United States.[41]

Malik Al Nasir dedicated a collection of poetry to Scott-Heron titled Ordinary Guy that contained a foreword by Jalal Mansur Nuriddin of The Last Poets. Scott-Heron recorded one of the poems in Nasir's book entitled Black & Blue in 2006.

In April 2009, on BBC Radio 4, poet Lemn Sissay presented a half-hour documentary on Gil Scott-Heron entitled Pieces of a Man,[42] having interviewed Gil Scott-Heron in New York a month earlier. Pieces of a Man was the first UK announcement from Scott-Heron of his forthcoming album and return to form. In November 2009, the BBC's Newsnight interviewed Scott-Heron for a feature titled The Legendary Godfather of Rap Returns.[43] In 2009, a new Gil Scott-Heron website, gilscottheron.net, was launched with a new track "Where Did the Night Go" made available as a free download from the site.

In 2010, Scott-Heron was booked to perform in Tel Aviv, Israel, but this attracted criticism from pro-Palestinian activists, who stated: "Your performance in Israel would be the equivalent to having performed in Sun City during South Africa's apartheid era... We hope that you will not play apartheid Israel". Scott-Heron responded by canceling the performance.[44]

I'm New Here

[edit]Scott-Heron released his album I'm New Here on independent label XL Recordings on February 9, 2010. Produced by XL label owner Richard Russell, I'm New Here was Scott-Heron's first studio album in 16 years. The pair began recording in 2007, but the majority of the album was recorded over the 12 months leading up to the release date, with engineer Lawson White at Clinton Studios in New York. I'm New Here is 28 minutes long with 15 tracks; however, casual asides and observations collected during recording sessions are included as interludes.[19]

The album attracted critical acclaim, with The Guardian's Jude Rogers declaring it one of the "best of the next decade",[45] while some have called the record "reverent" and "intimate", due to Scott-Heron's half-sung, half-spoken delivery of his poetry. In a music review for public radio network NPR, Will Hermes stated: "Comeback records always worry me, especially when they're made by one of my heroes ... But I was haunted by this record ... He's made a record not without hope but which doesn't come with any easy or comforting answers. In that way, the man is clearly still committed to speaking the truth".[46] Writing for music website Music OMH, Darren Lee provided a more mixed assessment of the album, describing it as rewarding and stunning, but he also states that the album's brevity prevents it "from being an unassailable masterpiece".[47]

Scott-Heron described himself as a mere participant, in a 2010 interview with The New Yorker:

This is Richard's CD. My only knowledge when I got to the studio was how he seemed to have wanted this for a long time. You're in a position to have somebody do something that they really want to do, and it was not something that would hurt me or damage me—why not? All the dreams you show up in are not your own.[19]

The remix version of the album, We're New Here, was released in 2011, featuring production by English musician Jamie xx, who reworked material from the original album.[48] Like the original album, We're New Here received critical acclaim.[49]

In April 2014, XL Recordings announced a third album from the I'm New Here sessions, titled Nothing New.[50] The album consists of stripped-down piano and vocal recordings and was released in conjunction with Record Store Day on April 19, 2014.

Death

[edit]"Gil Scott-Heron released poems as songs, recorded songs that were based on his earliest poems and writings, wrote novels and became a hero to many for his music, activism and his anger. There is always the anger – an often beautiful, passionate anger. An often awkward anger. A very soulful anger. And often it is a very sad anger. But it is the pervasive mood, theme and feeling within his work – and around his work, hovering, piercing, occasionally weighing down; often lifting the work up, helping to place it in your face. And for all the preaching and warning signs in his work, the last two decades of Gil Scott-Heron's life to date have seen him succumb to the pressures and demons he has so often warned others about."

– Fairfax New Zealand, February 2010[51]

Scott-Heron died on May 27, 2011, in New York City after a trip to Europe.[1][52] Scott-Heron had confirmed press speculation about his health when he disclosed in a 2008 New York Magazine interview that he had been HIV-positive for several years, and that he had been previously hospitalized for pneumonia.[39]

He was survived by his firstborn daughter Raquiyah "Nia" Kelly Heron from his relationship with Pat Kelly, his son Rumal Rackley from his relationship with Lurma Rackley,[53] daughter Gia Scott-Heron from his marriage to Brenda Sykes;[52] and daughter Chegianna Newton, who was 13 years old at the time of her father's death.[53][54] He is also survived by his sister Gayle, brother Denis Heron who once managed Scott-Heron,[55] his uncle Roy Heron,[18] and nephew Terrance Kelly, an actor and rapper who performs as Mr. Cheeks and is a member of Lost Boyz.[note 2]

Before his death Scott-Heron had been in talks with Portuguese director Pedro Costa over his film Horse Money to be screenwriter, composer and an actor.[56]

In response to Scott-Heron's death, Public Enemy's Chuck D stated "RIP GSH...and we do what we do and how we do because of you" on his Twitter account.[57] His UK publisher, Jamie Byng, called him "one of the most inspiring people I've ever met".[58] On hearing of the death, R&B singer Usher stated: "I just learned of the loss of a very important poet...R.I.P., Gil Scott-Heron. The revolution will be live!!".[59] Richard Russell, who produced Scott-Heron's final studio album, called him a "father figure of sorts to me",[60] while Eminem said "He influenced all of hip-hop".[61] Lupe Fiasco wrote a poem about Scott-Heron that was published on his website.[62]

Scott-Heron's memorial service was held at Riverside Church in New York City on June 2, 2011, where Kanye West performed "Lost in the World"[63] and "Who Will Survive in America",[64] two songs from West's album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.[63] The studio album version of West's "Who Will Survive in America" features a spoken-word excerpt by Scott-Heron.[65] Scott-Heron is buried at Kensico Cemetery in Westchester County in New York.

Scott-Heron was honored posthumously in 2012 by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[66] Charlotte Fox, member of the Washington, DC NARAS and president of Genesis Poets Music, nominated Scott-Heron for the award while a letter of support came from Grammy-winner and Grammy Hall of Fame inductee Bill Withers.[67]

Scott-Heron's memoir, The Last Holiday, was published in January 2012.[68] In her review for the Los Angeles Times, professor of English and journalism Lynell George wrote:

The Last Holiday is as much about his life as it is about context, the theater of late 20th century America — from Jim Crow to the Reagan '80s and from Beale Street to 57th Street. The narrative is not, however, a rise-and-fall retelling of Scott-Heron's life and career. It doesn't connect all the dots. It moves off-the-beat, at its own speed ... This approach to revelation lends the book an episodic quality, like oral storytelling does. It winds around, it repeats itself.[69]

Scott-Heron's estate

[edit]At the time of Scott-Heron's death, a will could not be found. Raquiyah Kelly-Heron filed papers in Manhattan's New York Surrogate's Court in August 2013, claiming that Rumal Rackley was not Scott-Heron's son and should be omitted from the musician's estate. According to the Daily News website, Rackley, Kelly-Heron and two other sisters were seeking a resolution to the management of the estate. Rackley stated in court papers that Scott-Heron had asked him to be the administrator of the estate. Scott-Heron's 1994 album Spirits was dedicated to "my son Rumal and my daughters Nia and Gia", and in court papers Rackley added that Scott-Heron "introduced me [Rackley] from the stage as his son".[70]

In 2011 Rackley had filed a suit against sister Gia Scott-Heron and her mother, Scott-Heron's first wife, Brenda Sykes believing they had unfairly attained US$250,000 of Scott-Heron's money. That case was settled for an undisclosed sum in early 2013 but the relationship between Rackley and Scott-Heron's two adult daughters had already become strained in the months after Gil's death. In her submission to the Surrogate Court, Kelly-Heron stated that a DNA test completed by Rackley in 2011—using DNA from Scott-Heron's brother—revealed that they "do not share a common male lineage", while Rackley has refused to undertake another DNA test. A hearing to address Kelly-Heron's filing was scheduled for late August 2013, but by March 2016 further information on the matter was not publicly available.[70] Rackley continued to serve as court-appointed administrator for the estate, and he donated material to the Smithsonian's new National Museum of African American History and Culture to be displayed when the museum opened in September 2016.

The case was decided in December 2018 when the Surrogate Court ruled that Rumal Rackley and his half-sisters are all legal heirs, and in a ruling issued in May 2019 Rackley was granted Letters of Administration.[71]

Influence and legacy

[edit]Scott-Heron's work has influenced writers, academics and musicians, from indie rockers to rappers. His work during the 1970s influenced and helped engender subsequent African-American music genres, such as hip hop and neo soul. He has been described by music writers as "the godfather of rap" and "the black Bob Dylan".[72] Jamiroquai lead singer Jay Kay performed "The Bottle" with him at the Phoenix Festival in 1993 when his band was starting out, and Kay said in a 2022 interview that Scott-Heron had whispered to him: "It's your turn now." In the same interview, Kay called him a "super influence for me" and "a master, a poet, and so much more".[73] In a review for Jamiroquai's Emergency on Planet Earth, Entertainment Weekly writer Marisa Fox wrote: "Gil Scott-Heron is still alive, but his ghost has already surfaced in the form of 22-year-old mad hatter Jay Kay and his trendy London acid-jazz group."[74]

Chicago Tribune writer Greg Kot comments on Scott-Heron's collaborative work with Jackson:

Together they crafted jazz-influenced soul and funk that brought new depth and political consciousness to '70s music alongside Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder. In classic albums such as 'Winter in America' and 'From South Africa to South Carolina,' Scott-Heron took the news of the day and transformed it into social commentary, wicked satire, and proto-rap anthems. He updated his dispatches from the front lines of the inner city on tour, improvising lyrics with an improvisational daring that matched the jazz-soul swirl of the music".[2]

Of Scott-Heron's influence on hip hop, Kot said he "presag[ed] hip-hop and infus[ed] soul and jazz with poetry, humor and pointed political commentary".[2] Ben Sisario of The New York Times wrote, "He [Scott-Heron] preferred to call himself a "bluesologist", drawing on the traditions of blues, jazz and Harlem renaissance poetics".[9] Tris McCall of The Star-Ledger writes that "The arrangements on Gil Scott-Heron's early recordings were consistent with the conventions of jazz poetry – the movement that sought to bring the spontaneity of live performance to the reading of verse".[75] A music writer later noted that "Scott-Heron's unique proto-rap style influenced a generation of hip-hop artists",[12] while The Washington Post wrote that "Scott-Heron's work presaged not only conscious rap and poetry slams, but also acid jazz, particularly during his rewarding collaboration with composer-keyboardist-flutist Brian Jackson in the mid- and late '70s".[76] The Observer's Sean O'Hagan discussed the significance of Scott-Heron's music with Brian Jackson, stating:

Together throughout the 1970s, Scott-Heron and Jackson made music that reflected the turbulence, uncertainty and increasing pessimism of the times, merging the soul and jazz traditions and drawing on an oral poetry tradition that reached back to the blues and forward to hip-hop. The music sounded by turns angry, defiant and regretful while Scott-Heron's lyrics possessed a satirical edge that set them apart from the militant soul of contemporaries such as Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield.[72]

Will Layman of PopMatters wrote about the significance of Scott-Heron's early musical work:

In the early 1970s, Gil Scott-Heron popped onto the scene as a soul poet with jazz leanings; not just another Bill Withers, but a political voice with a poet's skill. His spoken-voice work had punch and topicality. "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" and "Johannesburg" were calls to action: Stokely Carmichael if he'd had the groove of Ray Charles. "The Bottle" was a poignant story of the streets: Richard Wright as sung by a husky-voiced Marvin Gaye. To paraphrase Chuck D, Gil Scott-Heron's music was a kind of CNN for black neighborhoods, prefiguring hip-hop by several years. It grew from the Last Poets, but it also had the funky swing of Horace Silver or Herbie Hancock—or Otis Redding. Pieces of a Man and Winter in America (collaborations with Brian Jackson) were classics beyond category".[77]

Scott-Heron's influence over hip hop is primarily exemplified by his definitive single "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", sentiments from which have been explored by various rappers, including Aesop Rock, Talib Kweli and Common. In addition to his vocal style, Scott-Heron's indirect contributions to rap music extend to his and co-producer Jackson's compositions, which have been sampled by various hip-hop artists. "We Almost Lost Detroit" was sampled by Brand Nubian member Grand Puba ("Keep On"), Native Tongues duo Black Star ("Brown Skin Lady"), and MF Doom ("Camphor").[78] Additionally, Scott-Heron's 1980 song "A Legend in His Own Mind" was sampled on Mos Def's "Mr. Nigga",[79] the opening lyrics from his 1978 recording "Angel Dust" were appropriated by rapper RBX on the 1996 song "Blunt Time" by Dr. Dre,[80] and CeCe Peniston's 2000 song "My Boo" samples Scott-Heron's 1974 recording "The Bottle".[81]

In addition to the Scott-Heron excerpt used in "Who Will Survive in America", Kanye West sampled Scott-Heron and Jackson's "Home is Where the Hatred Is" and "We Almost Lost Detroit" for the songs "My Way Home" and "The People", respectively, both of which are collaborative efforts with Common.[82] Scott-Heron, in turn, acknowledged West's contributions, sampling the latter's 2007 single "Flashing Lights" on his final album, 2010's I'm New Here.[83]

Scott-Heron admitted ambivalence regarding his association with rap, remarking in 2010 in an interview for the Daily Swarm: "I don't know if I can take the blame for [rap music]".[84] As New York Times writer Sisario explained, he preferred the moniker of "bluesologist". Referring to reviews of his last album and references to him as the "godfather of rap", Scott-Heron said: "It's something that's aimed at the kids ... I have kids, so I listen to it. But I would not say it's aimed at me. I listen to the jazz station."[9] In 2013, Chattanooga rapper Isaiah Rashad recorded an unofficial mixtape called Pieces of a Kid, which was greatly influenced by Heron's debut album Pieces of a Man.

Following Scott-Heron's funeral in 2011, a tribute from publisher, record company owner, poet, and music producer Malik Al Nasir was published on The Guardian's website, titled "Gil Scott-Heron saved my life".[85]

In the 2018 film First Man, Scott-Heron is a minor character and is played by soul singer Leon Bridges.

He is one of eight significant people shown in mosaic at the 167th Street renovated subway station on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx that reopened in 2019.[86]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]| Title | Album details | Peak chart positions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [87] |

US Jazz [88] |

US R&B [89] |

BEL (FL) [90] |

FRA [91] |

IRE [92] |

SWI [93] |

UK [94] | ||

| Pieces of a Man |

|

— | — | — | 168 | — | — | — | — |

| Free Will |

|

— | — | — | —Bridges | — | — | —Released: 1977

Label: Arista |

— |

| The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron |

|

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Winter in America (with Brian Jackson) |

|

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| The First Minute of a New Day (with Brian Jackson and the Midnight Band) |

|

30 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — | — |

| From South Africa to South Carolina (with Brian Jackson) |

|

103 | — | 28 | — | — | — | — | — |

| It's Your World (with Brian Jackson) |

|

168 | — | 34 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Bridges (with Brian Jackson) |

|

130 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Secrets (with Brian Jackson) |

|

61 | — | 10 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1980 (with Brian Jackson) |

|

82 | — | 22 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Real Eyes |

|

159 | — | 63 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Reflections[95] |

|

106 | — | 21 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moving Target |

|

123 | — | 33 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Spirits |

|

— | 16 | 84 | — | — | — | — | — |

| I'm New Here |

|

— | 5 | 38 | 62 | 100 | 35 | 97 | 39 |

| We're New Here (with Jamie xx) |

|

— | — | — | 44 | 38 | 32 | — | 33 |

| Nothing New |

|

— | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| We're New Again – A Reimagining By Makaya McCraven[96] |

|

— | 3 | — | 93 | — | — | 58 | — |

| "—" denotes a recording that did not chart or was not released in that territory. | |||||||||

Live albums

[edit]| Title | Album details |

|---|---|

| Small Talk at 125th and Lenox |

|

| It's Your World (with Brian Jackson) |

|

| Tales of Gil Scott-Heron and His Amnesia Express[95] |

|

| Minister of Information: Live[95] |

|

| The Best of Gil Scott-Heron Live[97] |

|

| Save the Children[97] |

|

| Greatest Hits Live: Collector Series[97] |

|

| Live at the Town and Country 1988[97] |

|

Compilation albums

[edit]| Title | Album details |

|---|---|

| The Revolution Will Not Be Televised |

|

| The Best of Gil Scott-Heron |

|

| Glory: The Gil Scott-Heron Collection[95] |

|

| Ghetto Style[95] |

|

| Evolution & Flashback: The Very Best Of Gil Scott-Heron[95] |

|

| Anthology: Messages[97] |

|

Film scores

[edit]- The Baron (1977) — with Brian Jackson and Barnett Williams[98]

Charted songs

[edit]| Title | Year | Peak chart positions | Album | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US R&B [99] |

MEX Ing. [100] |

UK [94] | |||

| "The Bottle" (with Brian Jackson) | 1974 | 98 | — | — | Winter in America |

| "Johannesburg" (with Brian Jackson) | 1975 | 29 | — | — | From South Africa to South Carolina |

| "Angel Dust" | 1978 | 15 | — | — | Secrets |

| "Show Bizness" | 1979 | 83 | — | — | |

| "Shut 'Um Down" | 1980 | 68 | — | — | 1980 |

| "A Legend in His Own Mind" | 1981 | 86 | — | — | Real Eyes |

| "B-Movie"[101] | 49 | — | — | Reflections | |

| "Re-Ron" | 1984 | 72 | — | 89 | Non-album singles |

| "Space Shuttle" | 1990 | — | — | 77 | |

| "I'll Take Care of You" | 2011 | — | 32 | — | I'm New Here |

| "—" denotes a recording that did not chart or was not released in that territory. | |||||

Bibliography

[edit]| Year | Title | ISBN |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | The Vulture | 0862415284 |

| 1972 | The Nigger Factory | 0862415276 |

| 1990 | So Far, So Good | 0883781336 |

| 2001 | Now and Then: The Poems of Gil Scott-Heron | 086241900X |

| 2012 | The Last Holiday | 0857863010 |

Filmography

[edit]- Saturday Night Live, musical guest, December 13, 1975.

- Black Wax (1982). Directed by Robert Mugge.

- 5 Sides of a Coin (2004). Directed by Paul Kell

- The Revolution Will Not Be Televised (2005). Directed by Don Letts for BBC.

- The Paris Concert (2007).

- Tales of the Amnesia Express Live at the Town & Country (1988).

Notes

[edit]- ^ Onstage at the Black Wax Club in Washington, D.C., in 1982, Scott-Heron cited Harlem Renaissance writers Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen and Claude McKay as among those who had "taken the blues as a poetry form" in the 1920s and "fine-tuned it" into a "remarkable art form".

- ^ The Matriarch Agency (February 11, 2014). "DID YOU KNOW? Gil Scott-Heron's 1st born, @RAKELLYHERON & @MRCHEEKSLBFAM are cousins!". The Matriarch Agency on Twitter. Twitter. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Gil Scott-Heron, Spoken-Word Musician, Dies at 62". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c Kot, Greg (May 26, 2011). "Turn It Up: Gil Scott-Heron, soul poet, dead at 62". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Preston, Rohan B. (September 20, 1994). "Scott-Heron's Jazz Poetry Rich In Soul". The Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ Paul, Anna (March 2016). "An Introduction To Gil Scott-Heron In 10 Songs". The Culture Trip. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Woodstra, Chris; John Bush; Stephen Thomas Erlewine (2008). Old School Rap and Hip-hop. Backbeat Books. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-87930-916-9. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Bush, John. "Gil Scott-Heron - Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Backus, Rob (1976). Fire Music: A Political History of Jazz (2nd ed.). Vanguard Books. ISBN 091770200X.

- ^ Tyler-Ameen, Daoud (May 27, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron, Poet And Musician, Has Died". NPR. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 30, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Gil Scott-Heron in a live performance in 1982 with the Amnesia Express at the Black Wax Club, Washington, D.C. Black Wax (DVD). Directed by Robert Mugge.

- ^ Sharrock, David (May 28, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron: music world pays tribute to the 'Godfather of Rap'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Azpiri, Jon. Review: Pieces of a Man, AllMusic. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (January 9, 2012). "'The Last Holiday: A Memoir' by Gil Scott-Heron – Review". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Scott-Heron, Gil (January 8, 2012). "How Gil Scott-Heron and Stevie Wonder set up Martin Luther King Day". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 11, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ gilscottherononline.com

- ^ Limbong, Andrew (May 12, 2021). "Tina Turner, Jay-Z, Foo Fighters Among Those Inducted Into Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame". NPR. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Adjetey, Wendell Nii Laryea (2023). "Bridging Borders: African North Americans in Great Lakes Cities, 1920s–1940s". Journal of American History. 110 (1): 58–81. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaad149. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ^ a b Dell'Apa, Frank (December 4, 2008). "Giles Heron: Played for Celtic, father of musician". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilkinson, Alec (August 9, 2010). "New York is Killing Me". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 30, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Dacks, David (February 20, 2010). "Gil Scott-Heron Pioneering Poet". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Harold, Claudrena (July 22, 2011). "Deep in the Cane: The Southern Soul of Gil Scott-Heron". Southern Spaces. Atlanta, Georgia: Emory University. doi:10.18737/M7N31V. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Weiner, Jonah (June 23, 2011). "TRIBUTE: Gil Scott-Heron". Rolling Stone. No. 1133. p. 30. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Jazz Man – Biography". Home.clara.net. January 21, 2010. Archived from the original on May 5, 2003. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Scott-Heron, Gil (1972). Circle of stone: a novel (Thesis). Catalyst @ Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Nielsen, Aldon L. (2012). "Book Review: The Last Holiday: A Memoir". Critical Studies in Improvisation. 8 (2). Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron > Discography > Main Albums". All Media Guide, LLC. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (1995). Spin Alternative Record Guide (Ratings 1–10). New York City: Vintage Books. pp. 267–268. ISBN 0-679-75574-8. OCLC 32508105. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

his finest work

[permanent dead link] - ^ "Gil Scott-Heron – The Mind Of Gil Scott-Heron". Discogs. 1978. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "'Black Arrow' Gil Heron a trailblazer at Celtic – Father of famous jazz musician dies aged 87". The Scotsman. December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ "Holloway, Ron (Ronald Edward)", Encyclopedia of Jazz Musicians. Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Feeney, John (February 5, 2007). "Economic 'HIS-story' à la Gil Scott-Heron Growth is Madness!". Growthmadness.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Jazz Man – Biography". Home.clara.net. January 21, 2010. Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Salaam, Ntume ya; Salaam, Kalamu ya. "Breath of Life Presents – Gil Scott-Heron & His Music" (reviews)". ChickenBones: A Journal. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ "Musician Is Sent to Prison on Drug Charge". The New York Times. October 31, 2001. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Dahlen, Chris (May 29, 2002). "Blackalicious Blazing Arrow". Pitchfork. Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ Maycock, James (May 30, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron: Musician, writer and political activist whose years lost to drug addiction could not erase his influence". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ Wenn (July 8, 2006). "Scott-Heron To Serve Time For Breaking Rehab Deal". Contactmusic.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Genius Burning Brightly: The Unraveling of Gil Scott-Heron". Black Agenda Report. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Baram, Marcus (June 22, 2008). "The Weary Blues: Hip-hop godfather Gil Scott-Heron's out on parole, trying to stay clean, and ready for Carnegie Hall". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Inmate Information NYS Department of Correctional Services for Scott-Heron". Nysdocslookup.docs.state.ny.us. Archived from the original on June 2, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Busby, Margaret (February 2, 2012). "The Last Holiday: A Memoir by Gil Scott-Heron – review". The Observer. Archived from the original on June 2, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ "Radio 4 Programmes – Pieces of a Man". BBC. April 21, 2009. Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Stephen (November 16, 2009). "The Legendary Godfather of Rap Returns". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ "US activist, poet and singer dies". www.aljazeera.com. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Jude (November 19, 2009). "Best of the next decade: Gil Scott-Heron's I'm New Here". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ Hermes, Will (February 11, 2010). "A Surprising Record From Gil Scott Heron" (Audio upload). NPR. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Lee, Darren (February 8, 2010). "Gil Scott-Heron – I'm New Here". Music OMH. OMH. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Richter, Mischa (January 28, 2011). "Jamie Smith of the xx on Remixing Gil Scott-Heron, Working With Drake, New Music From the xx" Archived May 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Pitchfork. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ We're New Here Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More at Metacritic Archived May 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Metacritic. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ Gordon, Jeremy (April 1, 2014). "Gil Scott-Heron Album Nothing New Collects Stripped-Down 2008 Takes on Old Songs". Music Blog. Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "The anger and poetry of Gil Scott-Heron". Stuff.co.nz. February 10, 2010. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Gil Scott-Heron". The Telegraph. London. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Gil Scott-Heron Remembered as Tortured Genius" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, blAck Americaweb (May 31, 2011). Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ Milloy, Courtland (June 1, 2011). "Protest poet was more than 'The Revolution'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ Richmond, Norman Otis (November 2008). "Gil Heron, 81, father of Gil Scott-Heron, joins the ancestors". BlackVoices. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ Bahadur, Neil (July 21, 2015). "Interview: Pedro Costa". Film Comment. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron dies aged 62". NME. UK. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Sharrock, David (May 28, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron dies aged 62". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Soul giant Gil Scott-Heron dies". Toronto Sun. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "XL Recordings boss/producer: 'Gil Scott-Heron had immense talent and spirit'". NME. UK. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Dies Aged 62". MTV. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "R.I.P. Gil-Scott Heron – Lupe Fiasco Latest News". Lupefiasco.com. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Rogulewsk, Charley (June 3, 2011). "Kanye West raps at Gil Scott-Heron funeral". The Boombox. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Kanye West played Gil Scott-Heron's memorial service" Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Brooklyn Vegan (June 2, 2011). Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jayson (November 22, 2010). "Kanye West's My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy: A Track-By-Track Guide". MTV. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "The Official Site of Music's Biggest Night". GRAMMY.com. January 1, 1970. Archived from the original on May 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron". Gilscottherononline.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "The Last Holiday". Canongate.tv. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ George, Lynette (January 29, 2012). "Book review: 'The Last Holiday: A Memoir' by Gil Scott-Heron". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Gregorian, Dareh (August 11, 2013). "Gil Scott-Heron's daughter tries to get half-brother excluded from poet's estate". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Matter of Estate of Scott-Heron – Evidence Establishes Children's Paternity, Son Granted Letters of Administration". www.law.com. ALM Media Properties. May 10, 2019. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ a b O'Hagan, Sean (February 7, 2010). "Gil Scott-Heron: The Godfather of Rap Comes Back". The Observer. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Radio 2 Celebrates the 90s – Mixing Influences... with Jamiroquai – BBC Sounds". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Fox, Marisa (August 13, 1993). "Emergency on Planet Earth". EW.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ McCall, Tris (May 28, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron, poet, rhymer, and inspired protest singer, dead at 62" Archived June 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Star-Ledger. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (June 31, 1998), Review: "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post.

- ^ Layman, Will (February 11, 2010). "Gil Scott-Heron: I'm New Here". PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson vs Hip Hop". Samples VS. Hip Hop. February 3, 2010. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Search – Scott-Heron, Gil & Jackson, Brian Archived March 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The (Rap) Sample FAQ. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Staff (June 2011). Gil Scott-Heron: Remembering The "Godfather of Rap" | Music | BET Archived June 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. BET. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Ce Ce Peniston's "My Boo (The Things You Do)" sample of Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson's "The Bottle" Archived June 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. WhoSampled. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron". whosampled.com. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron on Coming From a Broken Home (Parts 1 & 2) Kanye West feat. Dwele and Connie Mitchell Flashing Lights". whosampled.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Gensler, Andy (March 10, 2010). "The Daily Swarm Interview: Gil Scott-Heron – The Revolution Will Not Be Blogged". The Daily Swarm. Archived from the original on March 13, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Al Nasir, Abdul Malik (June 19, 2011). "'Gil Scott-Heron saved my life'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ "WATCH: Newly Renovated Subway Station Celebrates Famous People With Bronx Ties Including Sonia Sotomayor, & Gil Scott-Heron". welcome2thebronx.com. January 11, 2019. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Chart History: The Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Chart History: Jazz Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Chart History: Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Discografie Gil Scott-Heron". Ultratop (in Dutch). Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Discographie Gil Scott-Heron". Les Charts (in French). Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Discography Gil Scott-Heron". Irish Charts. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Discographie Gil Scott-Heron". Swiss Hitparade (in German). Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Gil Scott-Heron". Official Charts. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Larkin, Colin, ed. (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195313734.

- ^ Kalia, Ammar (February 7, 2020). "Makaya McCraven and Gil Scott-Heron: We're New Again review – a modern classic revived". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Gil Scott-Heron Albums and Discography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "The Baron (1977): Full Cast & Crew". iMDb. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Chart History: Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron Chart History: Mexico Ingles Airplay". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "'B' Movie (Intro, Poem, Song)". November 7, 2014 – via YouTube.

Further reading

[edit]- Scott-Heron, Gil (August 20, 2013). The Last Holiday: A Memoir. Grove/Atlantic, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8021-9443-5.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Family website Archived April 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Discography at Discogs

- Text of "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised"

- Gil Scott-Heron interview on In Black America, October 1, 1984, at the American Archive of Public Broadcasting

- "An American Griot: Gil Scott-Heron in Conversation with Don Geesling" at Brooklyn Rail (November 2007)

- Interview with Gil Scott-Heron at NPR, from December 11, 2007

- Video interview Gil Scott-Heron interview with Brian Pace, part 1 of 2 with link to part 2. (February 17, 2009) at Vimeo

- Gil Scott-Heron

- 1949 births

- 2011 deaths

- 20th-century African-American musicians

- 20th-century American novelists

- African-American novelists

- African-American poets

- American male novelists

- American male poets

- American musicians of Jamaican descent

- American soul musicians

- American spoken word poets

- Arista Records artists

- Burials at Kensico Cemetery

- DeWitt Clinton High School alumni

- Ethical Culture Fieldston School alumni

- Flying Dutchman Records artists

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Johns Hopkins University alumni

- Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) alumni

- Musicians from Tennessee

- Novelists from Illinois

- People from Chelsea, Manhattan

- People with HIV/AIDS

- Poets from Illinois

- Progressive soul musicians

- Rappers from Chicago

- RCA Records artists

- Strata-East Records artists

- TVT Records artists

- Writers from Chicago

- XL Recordings artists