Gholam Mohammad Niazi

Gholam Mohammad Niazi | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1932 |

| Died | 29 May 1979 [1] |

| Nationality | Afghan |

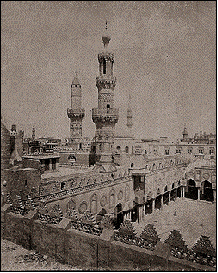

| Alma mater | Al-Azhar University |

| Era | Modern era |

Gholam Mohammad Niazi (Dari: ستاد غلام محمد نیازی; 1932–1979), was a leading professor at Kabul University, member of the Muslim Brotherhood, and the founder of the Islamic movement in Afghanistan.[2] In 1974 he was jailed for promoting the Islamist regime and was killed in jail in 1979.[2]

Niazi is remembered as the father of Islamism in Afghanistan.[3] He believed Islam had an important role in the social and political structure of Afghanistan.[3] Many of Afghanistan's most prominent politicians are influenced by the groundwork Niazi laid.

Early years

[edit]Gholam Mohammad Niazi was born the son of Abdul Nabi in 1932 in the Andar district of the Ghazni province which lies east of central Afghanistan to a Niazai Pashtun family.[2] He spent his early childhood in Andar before moving to Kabul for primary education.[2]

Education

[edit]

Niazi attended the local Hajwiri primary public school and then transferred to the Abu Haneefa school in Kabul.[2] He was very successful in school, so he was given the opportunity to further his studies in Egypt.[3] Niazi enrolled in Al-Azhar University in Cairo, where he obtained a master's degree in Islamic law in 1957.[3] He was one of the first Afghan students to study Islam in Egypt.[3] Niazi's educational path was uncommon in Afghanistan. Traditionally ulema studied in private madrasa in Afghanistan and the few Afghans that had the opportunity to study abroad studied in Pakistan.[3] The influx of Afghani students studying in Egypt brought new Middle Eastern political influence to Afghanistan.[3] Niazi led the way for new modernist and politicized intellectuals to abandon traditional madrasa.

Time in Egypt

[edit]During his studies in Cairo, Niazi joined the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.[3] The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood deeply influenced his visions of Islam and triggered his conception of an Islamic movement in Afghanistan.[3] Sayyid Qutb was his main source of intellectual inspiration. Specifically, Niazi's advocacy for a legal system exclusively based on Sharia law is rooted in Qutb’s works.[4]

In 1954, Nasser, the president of Egypt, outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood.[5] The Muslim Brotherhood became an underground organization.[5] This greatly shaped Niazi's experience of activism. The Muslim Brotherhood’s emphasis on popular support and connection with the masses inspired Niazi's political strategy.

Political career

[edit]

Niazi returned to Afghanistan from Egypt in 1957.[3] Upon arrival he spread his ideas in intellectual circles throughout Kabul.[3] He established a cell at an Abu Haneefa seminary in Paghman, a suburb of Kabul, and held informal meetings with other professors and intellectuals to spread his ideas.[6] Initially, they secretly gathered, but they became a formal political organization named Jamiat-e Islami in 1972.[3] Niazi was the president of the organization, which had as members such as Sebghatullah Mojaddidi and Minhajuddin Gahiz among others.[7]

Ideology

[edit]Niazi opposed westernization and communism because of their secular nature. He called for a spiritual revolution and emphasized the need to obtain a deep knowledge of Islam.[7] Niazi believed religion and science should go hand in hand. He worked towards establishing a new education model that followed the ideas and principles of the Muslim Brotherhood.[3] Niazi rigorously studied Islamic history and applied a political science lens to his learnings to understand the failures of past Islamic regimes. His publication, Majalle-ye Shariat (Review of Muslim Law) reinforced the Islamic movement and supported establishing an Islamic government in Afghanistan.[7] While his ideology was highly intellectual in nature, he also supported the formation of an armed branch within the movement to be prepared to take action if necessary.[7]

Muslim Youth

[edit]Many of the members of Jamiat-e Islami were professors, so they often spread their ideas directly to their students.[8] The Islamist ideas spread rapidly among students in Kabul, and the students created the Sazman-e Jawanan-e musalman (Muslim youth) in 1969.[6] They became a militant student organization that opposed Zionism, American and Soviet imperialism, the partition of Pakistan and the Afghan Monarchy.[3] They supported an Islamic social justice system with more equitable economic redistribution.[3] The student movement, inspired by Niazi, operated more overtly than Jamiat-e Islami and harbored important politicians such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Burhanuddin Rabbani.[3] When the communist party was established in 1965, the students of the Islamist political party overtly expressed their disagreements which caused a lot of disorder and resistance at Kabul University between 1965 and 1972.[3]

The secretive nature of Niazi's political engagement makes it difficult to evaluate his role in the Muslim Youth.[9] Rabbani claims that the student movement was obedient to Niazi and the Professors.[9] On the other hand, Hekmatyar argues that Muslim Youth and the Professors were completely separate, despite their shared ideological perspectives, because the Professors feared overt opposition to the Afghan political structure would put their positions at risk.[9]

Political participation

[edit]Niazi never directly participated in protests or demonstrations, but he instigated and inspired many.[10] He likely did not participate due to fear of government repression. In spring 1971, he initiated a demonstration in Kabul in reaction to the publication of a communist journal that he deemed blasphemy.[10] Tens of thousands of people demonstrated throughout the streets of Kabul, making it the largest demonstration in the history of the city.[10]

Despite his secretive nature, Niazi leveraged his position as the Dean of the Religious Science Faculty at Kabul University to advocate for official reforms.[3] He used his institutional power to expand the Islamic Studies department at the university and to amend the entrance exam to include religious knowledge as a compulsory subject.[7]

Additionally, Niazi tried to spread his ideas to other countries to trigger the creation of Islamic movements. In 1970, he and another professor attended the Peace Conference of Soviet Muslims, held in Tashkent.[11] At the conference, they expressed their support to the Muslims repressed under communism.[11] Despite having some personal connections with figures of political Islam in Egypt, Pakistan, and India, Niazi and the Professors were never able to create meaningful institutional ties with any Islamic Movement abroad.[3]

Challenges to the Islamic movement in Afghanistan

[edit]

Due to the covert nature of the Islamist movement, Gholam Mohammad Niazi and the Islamist movement faced numerous challenges. Initially, challenges to the movement were contained to the Kabul University campus and were mainly perpetrated by rival communist student groups, inspired by the Communist Party of Afghanistan.[3] As the Islamist movement grew new challenges arose outside of the university.[10]

Communism

[edit]The Islamist student movement led by Professor Gholam Mohammad Niazi faced numerous challenges from communist groups. Between 1965 and 1972, the university became a site of clashes between the anti-communist Islamists and the communist student groups.[3] These clashes took place on the university's different campuses and were bloody at times.[3]

Opposition of traditional Ulema

[edit]The ulema was initially skeptical of the Muslim youth movement taking place at the Kabul University.[5] Except for the ulema in three provinces, Nangrahar, Kunar and Laghman, there was little cooperation between religious leaders and Islamist student movements.[3] This was primarily due to mutual distrust between the two groups. The Ulema saw the youth movement as radical whereas the students saw the ulema as too conservative.[3] However, this distrust was not felt by Professor Mohammad Niazi, he, along with his fellow professors, wished to maintain friendly relations with the ulema.[3]

Government repression

[edit]After taking power through a bloodless coup in 1973, Mohammed Daud Khan proclaimed himself President of the newly instated Republic of Afghanistan which officially ended monarchy in the state.[10] His pro-soviet political party, the National Revolutionary Party, did not have the high levels of popularity originally envisaged. Daud undertook repressive action against the different factions of opposition beginning with the Islamists.[10] In 1974, in cooperation with Communist members of the police, Daud ordered the arrests of Islamist militants.[10] Among those arrested was Gholam Mohammad Niazi.[10] Many of those who were not arrested fled to Pakistan where the Islamist movement regrouped. In 1975, Pakistan exiled Afghan Islamist groups led violent attacks in the northeast of Afghanistan prompting further crackdowns by the Daud regime.[10]

Death

[edit]During the period of targeted Islamist repression by Daud's authoritarian regime, Gholam Mohammad Niazi was jailed in 1972, but he was released soon after.[2] In 1974 he was jailed again in Pul-e-Charkhi prison, along with many other Islamists.[7] Two hundred known prisoners, including Gholam Niazi and Mawlawi Fayzani, were kept without judgment.[3] After five years of imprisonment, Niazi was killed in prison alongside a large group of other Islamists.[1] Account of the circumstance of his death and other Islamists on 29 May 1979 is given below:

on 29 May 1979 a large group of Islamists were scheduled to be set free. as the prisoners began to disembark from a bus outside. They were due to sign their release papers before being taken to freedom; they had even submitted clothes for washing that morning, hoping to look respectable for their waiting families. But as soon as the first prisoner left the bus they realised their mistake. The lead inmate was blindfolded and grabbed by a guard, who tried to shackle him, causing him to hit out and alert the others. ‘Look my friends, they are killing us! Instead of releasing us they are killing us!’ he yelled. A cry of ‘God is greatest’ went up from the men on the bus as they appealed to the rest of the jail for help. ‘Oh Muslims, come down!’ they urged, but the entire prison remained silent except for one lone shout of solidarity which echoed through the cells. The guards blocked the exit gates and opened fire on the bus. The prisoners screamed and continued to call out God’s name as bullets tore into the vehicle

It is debated whether the Soviets were involved in his death, directly, indirectly, or at all.[7]

Legacy

[edit]

Gholam Mohammad Niazi is remembered as the father of Islamism in Afghanistan.[2] He was successful in transforming Islam into a political movement by utilizing the power of popular support.[2] However, the Islamic movement he established did not achieve unity. After Niazi's death, the remaining members of the Jamiat-e Islami were exiled, and the movement quickly fragmented.[2]

Notable affiliations

[edit]Burhanuddin Rabbani

[edit]Burhanuddin Rabbani was a professor at Kabul University who became the leader of the Jamiat-e Islami in 1972.[14] He succeeded Gholam Mohammad Niazi as founder and transitioned the organization from a secretive group into a formal Islamist political party.[10] Rabbani was exiled in 1974 due to the state's desire to repress opposing parties and views.[14] Under the Peshawar Accords, he served as the country's president from 1992 to 2001.[10]

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar

[edit]Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was an engineering student at Kabul University.[6] He was an Islamic student said who was attracted to Niazi's political ideology.[6] Hekmatyar was a member of the Muslim Youth.[6] While participating in demonstrations, he threw acid in women's faces and famously assassinated Saidal, a member of the Showla-i-Javid, a Mao-ist political party at Kabul University.[6] Later, in 1975 he founded the Hezb-i Islami, a segment of the Jamiat-e Islami who split under Rabbani's leadership.[10] In 1992, he became Prime Minister of the new post-Soviet regime.[10]

Abdul Rassul Sayyaf

[edit]Abdul Rassul Sayyaf was a professor at Kabul University.[3] In 1972, he became the deputy of the Jamiat-e Islami.[3] He was exiled from Afghanistan and then jailed for affiliation with Gholam Mohammad Niazi and his political group in 1973.[14] Sayyaf was highly against the political rule of then King Zahir Shah.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Sands, Chris; Qazizai, Fazelminallah (2019). Night letters : Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the Afghan Islamists who changed the world. London. ISBN 9781787381964.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Kakar, M. Hassan (1995). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982. Berkeley: The Regents of the University of California. ISBN 9780520085916.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Roy, Olivier (1984). "The Origins of the Islamist Movement in Afghanistan". Central Asian Survey. 3 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1080/02634938408400467. ISSN 0263-4937.

- ^ Qutb, Sayyid (1964). Milestones. Egypt: Kazi Publications. ISBN 9788172312442. OCLC 1029057710.

- ^ a b c Richard Paul Mitchell (1995). The Society of the Muslim Brothers. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195084373. OCLC 54644463.

- ^ a b c d e f Afghan, Faze̤l Aḥmed (2015). Conspiracies and atrocities in Afghanistan, 1700-2014. Indiana, US: Xlibris. ISBN 9781503572997. OCLC 944483093.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Faces of Afghanistan". Payam Aftab News Network. Translated by M. Ewaz. 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Hiro, Dilip (2002). War without End: The Rise of Islamist Terrorism and Global Response. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781136485565.

- ^ a b c Edwards, David B. (August 1993). "Summoning Muslims: Print, Politics, and Religious Ideology in Afghanistan". The Journal of Asian Studies. 52 (3): 609–628. doi:10.2307/2058856. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2058856. S2CID 154371923.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Dorronsoro, Gilles (2005). Revolution unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the present. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231136269. OCLC 56329374.

- ^ a b Supplement B: Soviet-Chinese reports on South East Asia. London: Central Asian Research Centre. 1970. OCLC 1000738586.

- ^ Sands, Chris; Qazizai, Fazelminallah (2019). Night letters : Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the Afghan Islamists who changed the world. London. pp. 139–140. ISBN 9781787381964.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "N. Alliance FM Pleased with Talk Results". Voice of America. 20 November 2001.

- ^ a b c d Sharma, Raghav (2016). Nation, ethnicity and the conflict in Afghanistan: political islam and the rise of ethno-politics 1992-1996. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781472471475. OCLC 974833761.

- ^ Edwards, David (2002). Before Taliban: Genealogies of the Afghan Jihad. Berkeley, CA: The Regents of the University of California. ISBN 9780520228610.