Géza Gyóni

Géza Gyóni (25 June 1884 – 25 June 1917) was a Hungarian war poet. He died in a Russian prisoner of war camp during the First World War. His many verse contributions to Hungarian literature are considered to be both immortal and the Hungarian language's equivalent to the poetry of Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Isaac Rosenberg.

Early life

[edit]Born Géza Áchim to "crusading Lutheran family" in the small village of Gyón, near Dabas, in Austria-Hungary.[1] Gyóni was one of the seven children of a pastor of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Hungary.[2]

After his younger brother died, Gyóni's mother became mentally ill and the future poet was sent to live with his uncle, who was also a Lutheran minister.[2]

After he graduated from the high school in Békéscsaba, the future poet began studying in the Lutheran seminary at Pozsony. But he was also drawn to writing and also became a newspaper correspondent and adopted the name of his birthplace as a pseudonym.[2]

Gyóni had to leave the seminary after he was injured while playing Russian roulette with a rival reporter. In the aftermath, he edited a rural newspaper for a time and then moved to Budapest to study economics.[2]

His first collection of poetry, named simply Versek (Poems) was published in the same year, 1903. This marked a very low period in his life, in which Gyóni sought to free himself from his father's demands and even attempted suicide, before being transferred to an administrative course which led to a job in Budapest. In the city he was increasingly drawn to journalists and poets, contributing to the literary journal Nyugat and beginning a long rivalry with the contemporary leading poet of Hungary Endre Ady, who he criticized in his second collection, Szomorú szemmel (With sorrowful eyes) in 1909.

Military service

[edit]

In November 1907, Gyóni was called up to the Austro-Hungarian Army, and spent eighteen months breaking rocks and building railway lines in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which he did not at all enjoy and which bred a very strong streak of pacifism in him. The "exercise" was finally called off in 1908.[3]

In Szabadka, Gyóni met and fell in love with the woman whose memory and infidelity were to taunt him in the POW camps in Siberia.[2]

During this time and the following two years he continued working on his poetry in Budapest, until he was recalled to active service during the Balkan Wars in 1912. In response, Gyóni wrote the great pacifist poem, Cézar, én nem megyek ("Caesar, I Will Not Go").[3]

His works in this period were later collected following his death, and posthumously published in 1917 as Élet szeretője (Lover of Life).

War poet

[edit]

In June 1914, police interrogation of the teenaged conspirators responsible for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, all of whom were members of the Unification or Death paramilitary organization, exposed that the pistols and bombs used, as well as cyanide capsules for use in the event of capture, had been covertly supplied by the Kingdom of Serbia's military intelligence chief Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević.[4] In response, Gyóni, like many other Austro-Hungarians, accepted the Government's description of, "a plot against us," by a Russo-Serbian military alliance and the need to fight, "a defensive war." Some Hungarian intellectuals, quite ironically, felt that World War I provided an excellent opportunity for revenge against the House of Romanov for Tsar Nicholas I's pivotal role in the defeat of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.[5]

Unlike his previous term of enlistment, Gyóni seemed to initially enjoy the soldier's life, regularly writing poetry which was sent back home from the front for publication.

According to Peter Sherwood, "Gyóni's first, still elated, poems from the Polish Front recall the 16th-century Hungarian poet Bálint Balassi's soldiers' songs of the marches, written during the campaign against the Turks."[6]

During the Siege of Przemyśl, has since been dubbed, "The Stalingrad of World War I",[7][8][9] Gyóni wrote poems to encourage the city's defenders and these verses were published there, under the title, Lengyel mezőkön, tábortűz melett (By Campfire on the Fields of Poland). A copy reached Budapest by aeroplane, which was an unusual feat in those days.[2]

In Hungary, the politician Jenő Rákosi, used the popularity of Gyóni's collection to set up Gyóni as a brave soldier-poet and as the paragon of the Hungarian poetic ideal, as opposed to the Symbolist poet Endre Ady, who was a pacifist.[2] Meanwhile, Gyóni's poetry took an increasingly depressive turn.

According to Erika Papp Faber, "His leaning toward Socialism and his anti-militarist attitude were, for a brief time, suspended, as he was caught up in the general patriotic fervor at the outbreak of World War I. But once he experienced the horrors of war first hand, he soon lost his romantic notions, and returned to the more radical positions of his youth, as it evident in his further volumes."[10]

One of his poems from this period, Csak egy éjszakára (For Just One Night), in which he calls for Hungary's war profiteers, industrialists, and armchair patriots to come and spend just one night in the trenches, became a prominent anti-war poem and its popularity has lasted well beyond the end of the First World War.

Prisoner of war

[edit]

In March 1915, Gyóni was taken prisoner when the Austro-Hungarian Army surrendered Przemyśl to the Imperial Russian Army, who celebrated by immediately launching a pogrom against the city's Jewish population.[11][12] Regular outbreaks of anti-semitic violence, as well as the religious persecution of Rusins and Ukrainians who belonged to the Eastern Catholic Churches, were to continue until the Imperial Russian Army was humiliatingly driven out of the region by the Gorlice–Tarnów offensive and into the Great Retreat of 1915.

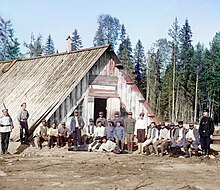

Meanwhile, Gyóni was permitted to remain with his younger brother, Mihály Áchim, who had also been captured. Together they endured a lengthy nine-month journey between POW camps and receiving areas in Kiev, Moscow, Alatyr, Petropavlovsk, Omsk and finally Krasnoyarsk in Siberia. In the Krasnoyarsk camp, which was located upon a plateau 7 km outside of the city and held more than 13,000 Imperial German and Austro-Hungarian POWs,[13] Gyóni learnt of the full actions of Jenő Rákosi, the politician who had been weaponizing his verse for wartime propaganda. Gyóni had only heard rumours before and was enraged by what he learned.

Central Powers POWs who spoke Slavic languages were generally treated favorably by their Tsarist captors, due to both extreme Slavophilism and also in the hopes of recruiting them to switch sides and fight for the Allies. German- and Hungarian-speaking prisoners, on the other hand, were treated so inhumanely and with such unnecessary brutality that, according to historian Alfred Maurice de Zayas, the post-Armistice government of the Weimar Republic spent many years investigating and ultimately ruled that the treatment of POWs in Russian Imperial custody was a war crime according to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.[14]

Even so, Gyóni went on to write perhaps his finest poetry as a POW in Krasnoyarsk and produced the collection Levelek a kálváriáról és más költemények (Letters from Golgotha and Other Poems) which was published in 1916, based on manuscripts sent through the lines.

According to Erika Papp Faber, "The framework of this volume is provided by his unfaithful sweetheart and is filled with homesickness and visions of reconciliation with her."[2]

Death

[edit]Gyóni died in the camp on his 33rd birthday, shortly after having a psychotic breakdown in response to his brother's death on 8 June. He was buried beside his brother at the Troitsky Cemetery in Krasnoyarsk.

Gyóni wrote a poem in enemy captivity which represented his attitude to life entitled Magyar bárd sorsa (A Hungarian bard's fate):[6][15]

- Nekem magyar bárd sorsát mérték:

- Úgy hordom végig a világon

- Véres keresztes magyarságom,

- Mint zarándok a Krisztus képét.[15]

A Hungarian bard's is my fate

To carry across the world

My bloodied, crusading Magyarhood

Like a pilgrim with a picture of Christ.

—Géza Gyóni

Legacy

[edit]

More than 411,000 Central Powers POWs held in Russian Imperial custody, the majority of whom were Austro-Hungarian servicemen, died due to the conditions of their imprisonment. This represents a total of 17.6% out of all POWs held by the Russian Empire.[16]

Géza Gyóni's last collection, Rabságban (In Captivity), consists of poems that were brought back to the truncated post-Treaty of Trianon Kingdom of Hungary by a fellow POW. It was posthumously published in 1919.[17]

According to Erika Papp Faber, "Loránt Czigány, the literary historian, called Gyóni 'a war poet of considerable talent,' while others, among them László Cs. Szabó, observe that Gyóni was not as outstanding a 'singer of the trenches' as were some French and English poets of World War I. Be that as it may, Géza Gyóni is a writer whose entire life and writings reflect the events of his time and help in understanding that period of European history."[17]

Géza Gyóni's anti-war poem Csak egy éjszakára ("For Just One Night"), remains very popular and is still taught in Hungarian schools. It has been translated into English by Canadian poet Watson Kirkconnell and by Hungarian American poet Erika Papp Faber.

Although Kirkconnell's translation renders Gyóni's poem into the same idiom as British war poets Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, and Isaac Rosenberg,[18] Erika Papp Faber's version is far more faithful to the original poem in Hungarian.[19]

Collections

[edit]- 1903 – Versek (Poems)

- 1909 – Szomorú szemmel (With sorrowful eyes)

- 1914 – Lengyel mezőkön, tábortűz melett (By the campfire on Polish prairies)

- 1916 – Levelek a kálváriáról és más költemények (Letters from Calvary and Other Poems)

- 1917 – Élet szeretője (Lover of Life) (posthumous)

- 1919 – Rabságban (In Prison) (posthumous)

Literature

[edit]- Cross, Tim, The Lost Voices of World War I, Bloomsbury Publishing, Great Britain: 1988. ISBN 0-7475-4276-7

References

[edit]- ^ Tim Cross (1988), The Lost Voices of World War I, page 348.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Erika Papp Faber (2012), A Sampler of Hungarian Poetry, Romanika Kiadó, Budapest. p. 120.

- ^ a b Tim Cross (1988), The Lost Voices of World War I, p. 348.

- ^ Edited by Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis (3002), Intimate Voices from the First World War, William Morrow. pp. 3-11.

- ^ Tim Cross (1988), The Lost Voices of World War I, pp. 348–349.

- ^ a b Tim Cross (1988), The Lost Voices of World War I, p. 349.

- ^ For Just One Night, by Geza Gyóni.

- ^ Watson, Alexander (2020-07-22). "World War I's Stalingrad: The Siege of Przemyśl and Europe's Bloodlands". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Wilson, Peter H. (2023). Iron and Blood: A Military History of the German-Speaking Peoples since 1500 (1st ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-674-98762-3.

- ^ Erika Papp Faber (2012), A Sampler of Hungarian Poetry, Romanika Kiadó, Budapest. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Palmer, Svetlana; Wallis, Sarah (2003). A War in Words. Simon & Schuster. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-7432-4831-7.

- ^ Edited by Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis (3002), Intimate Voices from the First World War, William Morrow. pp. 69-93.

- ^ Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt, Elsa Brändström (1969), pp. 174–187.

- ^ de Zayas, Alfred (1989), The Wehrmacht War Crimes Bureau, 1939–1945 (with Walter Rabus). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989; ISBN 0-8032-9908-7. pp. 9–10, 279 note 42.

- ^ a b "Gyóni Géza: Magyar bárd sorsa". www.szozat.org.

- ^ Sumpf, Alexandre (2014). La Grande guerre oubliée: Russie, 1914-1918 [The Great Forgotten War: Russia, 1914-1918] (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-04045-1. pp. 137, 233.

- ^ a b Erika Papp Faber (2012), A Sampler of Hungarian Poetry, Romanika Kiadó, Budapest. p. 121.

- ^ Tim Cross (1988), The Lost Voices of World War I, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Erika Papp Faber (2012), A Sampler of Hungarian Poetry, Romanika Kiadó, Budapest. pp. 124–125.

- 1884 births

- 1917 deaths

- 20th-century Hungarian poets

- 20th-century Hungarian male writers

- 20th-century Lutherans

- 19th-century Lutherans

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel killed in World War I

- Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war in World War I

- Crimes against prisoners of war

- Hungarian Lutherans

- Hungarian male poets

- Hungarian World War I poets

- Lutheran poets

- Poètes maudits

- World War I prisoners of war held by Russia

- World War I crimes by the Russian Empire