Deutsche Physik

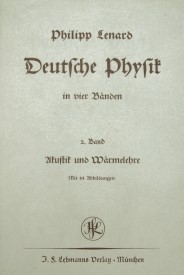

Deutsche Physik (German: [ˈdɔʏtʃə fyˈziːk], lit. "German Physics") or Aryan Physics (German: Arische Physik) was a nationalist movement in the German physics community in the early 1930s which had the support of many eminent physicists in Germany. The term was taken from the title of a four-volume physics textbook by Nobel laureate Philipp Lenard in the 1930s.

Deutsche Physik was opposed to the work of Albert Einstein and other modern theoretically based physics, which was disparagingly labeled "Jewish physics" (German: Jüdische Physik).

Origins

[edit]

This movement began as an extension of a German nationalistic movement in the physics community which went back to the start of World War I with Austria's declaration of war on 28 July 1914. On 25 August 1914, during the German Rape of Belgium, German troops used petrol to set fire to the library of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.[1][2][3][4] The burning of the library led to a protest note which was signed by eight distinguished British scientists, namely William Bragg, William Crookes, Alexander Fleming, Horace Lamb, Oliver Lodge, William Ramsay, Lord Rayleigh, and J. J. Thomson. In 1915, this led to a counter-reaction in the form of an "appeal" formulated by Wilhelm Wien and addressed to German physicists and scientific publishers, which was signed by sixteen German physicists, including Arnold Sommerfeld and Johannes Stark. They claimed that German character had been misinterpreted and that attempts made over many years to reach an understanding between the two countries had obviously failed. Therefore, they opposed the use of the English language by German scientific authors, editors of books, and translators.[5] A number of German physicists, including Max Planck and the especially passionate Philipp Lenard, a scientific rival of J. J. Thomson, had then signed further "declarations", so that gradually a "war of the minds"[6] broke out. On the German side it was suggested to avoid an unnecessary use of English language in scientific texts (concerning, e.g., the renaming of German-discovered phenomena with perceived English-derived names, such as "X-ray" instead of "Röntgen ray"). It was stressed, however, that this measure should not be misunderstood as a rejection of British scientific thought, ideas and stimulations.

After the war, the perceived affronts of the Treaty of Versailles kept some of these nationalistic feelings running high, especially in Lenard, who had already complained about England in a small pamphlet at the beginning of the war.[7] When, on 26 January 1920, the former naval cadet Oltwig von Hirschfeld tried to assassinate German Finance minister Matthias Erzberger, Lenard sent Hirschfeld a telegram of congratulation.[8] After the 1922 assassination of politician Walther Rathenau, the government ordered flags flown at half mast on the day of his funeral, but Lenard ignored the order at his institute in Heidelberg. Socialist students organized a demonstration against Lenard, who was taken into protective custody by state prosecutor Hugo Marx.[9]

During the early years of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein's theory of relativity caused bitter controversy within the worldwide physics community. There were many physicists, especially the "old guard", who were suspicious of the intuitive meanings of Einstein's theories. While the response to Einstein was based partly on his concepts being a radical break from earlier theories, there was also an anti-Jewish element to some of the criticism. The leading theoretician of the Deutsche Physik type of movement was Rudolf Tomaschek, who had re-edited the famous physics textbook Grimsehl's Lehrbuch der Physik. In that book, which consists of several volumes, the Lorentz transformation was accepted, as well as the old quantum theory. However, Einstein's interpretation of the Lorentz transformation was not mentioned, and Einstein's name was completely ignored. Many classical physicists resented Einstein's dismissal of the notion of a luminiferous aether, which had been a mainstay of their work for the majority of their productive lives. They were not convinced by the empirical evidence for relativity. They believed that the measurements of the perihelion of Mercury and the null result of the Michelson–Morley experiment might be explained in other ways, and the results of the Eddington eclipse experiment were experimentally problematic enough to be dismissed as meaningless by the more devoted doubters. Many of them were very distinguished experimental physicists, and Lenard was himself a Nobel laureate in Physics.[10]

Under the Third Reich

[edit]

When the Nazis entered the political scene, Lenard quickly attempted to ally himself with them, joining the party at an early stage. With another Nobel laureate in Physics, Johannes Stark, Lenard began a core campaign to label Einstein's relativity as Jewish physics.

Lenard[11] and Stark benefited considerably from this Nazi support. Under the rallying cry that physics should be more "German" and "Aryan", Lenard and Stark embarked on a Nazi-endorsed plan to replace physicists at German universities with "Aryan physicists". By 1935, though, this campaign was superseded by the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. There were no longer any Jewish physics professors in Germany, since under the Nuremberg Laws, Jews were not allowed to work in universities. Stark in particular also tried to install himself as the national authority on "German" physics under the principle of Gleichschaltung (literally, "coordination") applied to other professional disciplines. Under this Nazi-era paradigm, academic disciplines and professional fields followed a strictly linear hierarchy created along ideological lines.

The figureheads of "Aryan physics" met with moderate success, but the support from the Nazi Party was not as great as Lenard and Stark would have preferred. They began to fall from influence after a long period of harassment of quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg, which included getting him labeled a "White Jew" in Das Schwarze Korps. Heisenberg was an extremely eminent physicist, and the Nazis realized that they were better off with him rather than without, however "Jewish" his theory might be in the eyes of Stark and Lenard. In an historic moment, Heisenberg's mother rang Heinrich Himmler's mother and asked her whether she would please tell the SS to give "Werner" a break. After beginning a full character evaluation, which Heisenberg both instigated and passed, Himmler forbade further attack on the physicist. Heisenberg would later employ his "Jewish physics" in the German project to develop nuclear fission for the purposes of nuclear weapons or nuclear energy use. Himmler promised Heisenberg that after Germany won the war, the SS would finance a physics institute to be directed by Heisenberg.[12]

Lenard began to play less and less of a role, and soon Stark ran into even more difficulty, as other scientists and industrialists known for being exceptionally "Aryan" came to the defense of relativity and quantum mechanics. As historian Mark Walker puts it:[citation needed]

... despite his best efforts, in the end his science was not accepted, supported, or used by the Third Reich. Stark spent a great deal of his time during the Third Reich fighting with bureaucrats within the Nazi state. Most of the Nazi leadership either never supported Lenard and Stark, or abandoned them in the course of the Third Reich.

Effect on the German nuclear program

[edit]It is occasionally put forth[13] that there is a great irony in the Nazis' labeling modern physics as "Jewish science", since it was exactly modern physics—and the work of many European exiles—which was used to create the atomic bomb. Even if the German government had not embraced Lenard and Stark's ideas, the German antisemitic agenda was enough by itself to destroy the Jewish scientific community in Germany. Furthermore, the German nuclear weapons program was never pursued with anywhere near the vigor of the Manhattan Project in the United States, and for that reason would likely not have succeeded in any case.[14] The movement did not actually go as far as preventing the nuclear energy scientists from using quantum mechanics and relativity,[15] but the education of young scientists and engineers suffered, not only from the loss of the Jewish scientists but also from political appointments and other interference.

See also

[edit]- Ahnenerbe (Nazi archaeology)

- Criticism of the theory of relativity

- Deutsche Mathematik

- Japhetic theory

- Lysenkoism

- Politicization of science

- Suppressed research in the Soviet Union

- Wilhelm Müller (physicist)

References

[edit]- ^ Kramer, Alan (2008). Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. Penguin. ISBN 9781846140136.

- ^ Gibson, Craig (30 January 2008). "The culture of destruction in the First World War". Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ LOST MEMORY – LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES DESTROYED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ( Archived 5 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Theodore Wesley Koch. The University of Louvain and its library. J.M. Dent and Sons, London and Toronto, 1917. Pages 21–23. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013 - ^ For the full German text of Wilhelm Wien's appeal see: The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science (J. L. Heilbron, ed.), Oxford University Press, New York 2003, p. 419.

- ^ Stephan L. Wolff: Physiker im Krieg der Geister, Zentrum für Wissenschafts- und Technikgeschichte, München 2001, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ Philipp Lenard, England und Deutschland zur Zeit des großen Krieges – Geschrieben Mitte August 1914, publiziert im Winter 1914, Heidelberg.

- ^ Heinz Eisgruber: Völkische und deutsch-nationale Führer, 1925.

- ^ Der Fall Philipp Lenard – Mensch und "Politiker", Physikalische Blätter 23, No. 6, 262–267 (1967).

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1905". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Philipp Lenard: Ideelle Kontinentalsperre, München 1940.

- ^ Padfield, Peter (1990), Himmler, New York: Henry Holt.

- ^ Einstein: His Life and Universe. Chapter 21: The Bomb

- ^ German Nuclear Weapons

- ^ Jeremy Bernstein, Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall, 2001, Springer-Verlag

Further literature

[edit]- Ball, Philip, Serving the Reich: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics Under Hitler (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

- Beyerchen, Alan, Scientists under Hitler: Politics and the physics community in the Third Reich (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977).

- Hentschel, Klaus, ed. Physics and National Socialism: An anthology of primary sources (Basel: Birkhaeuser, 1996).

- Philipp Lenard: Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen Band IV. Herausgegeben und kritisch kommentiert von Charlotte Schönbeck. [Posthumously, German Language.] Berlin: GNT-Verlag, 2003. ISBN 978-3-928186-35-3. Introduction, Content.

- Walker, Mark, Nazi science: Myth, truth, and the German atomic bomb (New York: HarperCollins, 1995).

External links

[edit] Works related to The Bad Nauheim Debate at Wikisource

Works related to The Bad Nauheim Debate at Wikisource