Darwin's finches

| Darwin's finches | |

|---|---|

| |

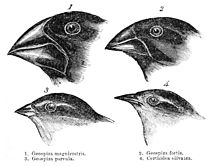

| Large ground finch, Medium ground finch Small tree finch, Green warbler-finch | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Superfamily: | Emberizoidea |

| Family: | Thraupidae |

| Groups included | |

Darwin's finches (also known as the Galápagos finches) are a group of about 18 species of passerine birds.[1][2][3][4] They are well known for being a classic example of adaptive radiation and for their remarkable diversity in beak form and function.[5] They are often classified as the subfamily Geospizinae or tribe Geospizini. They belong to the tanager family and are not closely related to the true finches. The closest known relative of the Galápagos finches is the South American dull-coloured grassquit (Asemospiza obscura).[6] They were first collected when the second voyage of the Beagle visited the Galápagos Islands, with Charles Darwin on board as a gentleman naturalist. Apart from the Cocos finch, which is from Cocos Island, the others are found only on the Galápagos Islands.

The term "Darwin's finches" was first applied by Percy Lowe in 1936, and popularised in 1947 by David Lack in his book Darwin's Finches.[7][8] Lack based his analysis on the large collection of museum specimens collected by the 1905–06 Galápagos expedition of the California Academy of Sciences, to whom Lack dedicated his 1947 book. The birds vary in size from 10 to 20 cm (4 to 8 in) and weigh between 8 and 38 grams (0.3 and 1.3 oz). The smallest are the warbler-finches and the largest is the vegetarian finch. The most important differences between species are in the size and shape of their beaks, which are highly adapted to different food sources. Food availability was different among the islands of the Galapagos and could also change dramatically due to natural events such as droughts. The birds are all dull-coloured. They are thought to have evolved from a single finch species that came to the islands more than a million years ago.[9]

Darwin's theory

[edit]During the survey voyage of HMS Beagle, Darwin was unaware of the significance of the birds of the Galápagos. He had learned how to preserve bird specimens from John Edmonstone while at the University of Edinburgh and had been keen on shooting, but he had no expertise in ornithology and by this stage of the voyage concentrated mainly on geology.[10] In Galápagos he mostly left bird shooting to his servant Syms Covington.[11] Nonetheless, these birds were to play an important part in the inception of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection.

On the Galápagos Islands and afterward, Darwin thought in terms of "centres of creation" and rejected ideas concerning the transmutation of species.[12] From Henslow's teaching, he was interested in the geographical distribution of species, particularly links between species on oceanic islands and on nearby continents. On Chatham Island, he recorded that a mockingbird was similar to those he had seen in Chile, and after finding a different one on Charles Island he carefully noted where mockingbirds had been caught.[10] In contrast, he paid little attention to the finches. When examining his specimens on the way to Tahiti, Darwin noted that all of the mockingbirds on Charles Island were of one species, those from Albemarle of another, and those from James and Chatham Islands of a third. As they sailed home about nine months later, this, together with other facts, including what he had heard about Galápagos tortoises, made him wonder about the stability of species.[13][14]

- Geospiza magnirostris

- Geospiza parvula

- Certhidea olivacea

- Geospiza fortis

Following his return from the voyage Darwin presented the finches to the Zoological Society of London on 4 January 1837, along with other mammal and bird specimens that he had collected. The bird specimens, including the finches, were given to John Gould, the famous English ornithologist, for identification. Gould set aside his paying work and at the next meeting, on 10 January, reported that the birds from the Galápagos Islands that Darwin had thought were blackbirds, "gross-beaks" and finches were actually "a series of ground Finches which are so peculiar [as to form] an entirely new group, containing 12 species." This story made the newspapers.[15][16]

Darwin had been in Cambridge at that time. In early March, he met Gould again and for the first time to get a full report on the findings, including the point that his Galápagos "wren" was another closely allied species of finch. The mockingbirds that Darwin had labelled by island were separate species rather than just varieties. Gould found more species than Darwin had expected,[17] and concluded that 25 of the 26 land birds were new and distinct forms, found nowhere else in the world but closely allied to those found on the South American continent.[16] Darwin now saw that, if the finch species were confined to individual islands, like the mockingbirds, this would help to account for the number of species on the islands, and he sought information from others on the expedition. Specimens had also been collected by Captain Robert FitzRoy, FitzRoy's steward Harry Fuller, and Darwin's servant Covington, who had labelled them by island.[18] From these, Darwin tried to reconstruct the locations from where he had collected his own specimens. The conclusions supported his idea of the transmutation of species.[16]

Text from The Voyage of the Beagle

[edit]At the time that he rewrote his diary for publication as Journal and Remarks (later The Voyage of the Beagle), he described Gould's findings on the number of birds, noting that "Although the species are thus peculiar to the archipelago, yet nearly all in their general structure, habits, colour of feathers, and even tone of voice, are strictly American".[19] In the first edition of The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin said that

It is very remarkable that a nearly perfect gradation of structure in this one group can be traced in the form of the beak, from one exceeding in dimensions that of the largest gros-beak, to another differing but little from that of a warbler".[20]

By the time the first edition was published, the development of Darwin's theory of natural selection was in progress. For the 1845 second edition of The Voyage (now titled Journal of Researches), Darwin added more detail about the beaks of the birds, and two closing sentences which reflected his changed ideas:

Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends."[21][22]

The remaining land-birds form a most singular group of finches, related to each other in the structure of their beaks, short tails, form of body and plumage: There are thirteen species, which Mr. Gould has divided into four subgroups. All these species are peculiar to this archipelago; and so is the whole group, with the exception of one species of the sub-group Cactornis, lately brought from Bow Island, in the Low Archipelago. Of Cactornis, the two species may be often seen climbing about the flowers of the great cactus-trees; but all the other species of this group of finches, mingled together in flocks, feed on the dry and sterile ground of the lower districts. The males of all, or certainly of the greater number, are jet black; and the females (with perhaps one or two exceptions) are brown. The most curious fact is the perfect gradation in the size of the beaks in the different species of Geospiza, from one as large as that of a hawfinch to that of a chaffinch, and (if Mr. Gould is right in including his sub-group, Certhidea, in the main group) even to that of a warbler. The largest beak in the genus Geospiza is shown in Fig. 1, and the smallest in Fig. 3; but instead of there being only one intermediate species, with a beak of the size shown in Fig. 2, there are no less than six species with insensibly graduated beaks. The beak of the sub-group Certhidea, is shown in Fig. 4. The beak of Cactornis is somewhat like that of a starling, and that of the fourth subgroup, Camarhynchus, is slightly parrot-shaped. Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends. In a like manner it might be fancied that a bird originally a buzzard, had been induced here to undertake the office of the carrion-feeding Polybori of the American continent.[23]

Text from On the Origin of Species

[edit]Darwin discussed the divergence of species of birds in the Galápagos more explicitly in his chapter on geographical distribution in On the Origin of Species:

The most striking and important fact for us in regard to the inhabitants of islands, is their affinity to those of the nearest mainland, without being actually the same species. [In] the Galapagos Archipelago ... almost every product of the land and water bears the unmistakable stamp of the American continent. There are twenty-six land birds, and twenty-five of these are ranked by Mr. Gould as distinct species, supposed to have been created here; yet the close affinity of most of these birds to American species in every character, in their habits, gestures, and tones of voice, was manifest. ... The naturalist, looking at the inhabitants of these volcanic islands in the Pacific, distant several hundred miles from the continent, yet feels that he is standing on American land. Why should this be so? Why should the species which are supposed to have been created in the Galapagos Archipelago, and nowhere else, bear so plain a stamp of affinity to those created in America? There is nothing in the conditions of life, in the geological nature of the islands, in their height or climate, or in the proportions in which the several classes are associated together, which resembles closely the conditions of the South American coast: In fact there is a considerable dissimilarity in all these respects. On the other hand, there is a considerable degree of resemblance in the volcanic nature of the soil, in climate, height, and size of the islands, between the Galapagos and Cape de Verde Archipelagos: But what an entire and absolute difference in their inhabitants! The inhabitants of the Cape de Verde Islands are related to those of Africa, like those of the Galapagos to America. I believe this grand fact can receive no sort of explanation on the ordinary view of independent creation; whereas on the view here maintained, it is obvious that the Galapagos Islands would be likely to receive colonists, whether by occasional means of transport or by formerly continuous land, from America; and the Cape de Verde Islands from Africa; and that such colonists would be liable to modification — the principle of inheritance still betraying their original birthplace.[24]

Polymorphism in Darwin's finches

[edit]Whereas Darwin spent just five weeks in the Galápagos, and David Lack spent three months, Peter and Rosemary Grant and their colleagues have made research trips to the Galápagos for about 30 years, particularly studying Darwin's finches.

Females are dimorphic in song type: songs A and B are quite distinct. Also, males with song A have shorter bills than B males, another clear difference. With these beaks, males are able to feed differently on their favourite cactus, the prickly pear Opuntia. Those with long beaks are able to punch holes in the cactus fruit and eat the fleshy aril pulp, which surrounds the seeds, whereas those with shorter beaks tear apart the cactus base and eat the pulp and any insect larvae and pupae (both groups eat flowers and buds). This dimorphism clearly maximises their feeding opportunities during the non-breeding season when food is scarce.

If the population is panmictic,[25][26] then Geospiza conirostris exhibits a balanced genetic polymorphism and not, as originally supposed, a case of nascent sympatric speciation. The selection maintaining the polymorphism maximises the species' niche by expanding its feeding opportunity. The genetics of this situation cannot be clarified in the absence of a detailed breeding program, but two loci with linkage disequilibrium[27] is a possibility.

Another interesting dimorphism is for the bills of young finches, which are either 'pink' or 'yellow'. All species of Darwin's finches exhibit this morphism, which lasts for two months. No interpretation of this phenomenon is known.[28]

Taxonomy

[edit]Family

[edit]For some decades, taxonomists have placed these birds in the family Emberizidae along with the New World sparrows and Old World buntings.[29] However, the Sibley–Ahlquist taxonomy puts Darwin's finches with the tanagers (Monroe and Sibley 1993), and at least one recent work follows that example (Burns and Skutch 2003). The American Ornithologists' Union, in its North American checklist, places the Cocos finch in the Emberizidae, but with an asterisk indicating that the placement is probably wrong (AOU 1998–2006); in its tentative South American check-list, the Galápagos species are incertae sedis, of uncertain place (Remsen et al. 2007).

Species

[edit]

- Genus Geospiza

- Genovesa ground finch (Geospiza acutirostris)

- Española cactus finch (Geospiza conirostris)

- Sharp-beaked ground finch (Geospiza difficilis)

- Vampire finch (Geospiza septentrionalis)

- Medium ground finch (Geospiza fortis)

- Genovesa cactus finch (Geospiza propinqua)

- Small ground finch (Geospiza fuliginosa)

- Large ground finch (Geospiza magnirostris)

- Common cactus finch (Geospiza scandens)

- Big Bird (not yet formally named): In 1981, a hybrid male arrived at Daphne Major island. Its mating with local Galapagos finches (specifically G. fortis) has produced a new "big bird" population that can exploit previously unexploited food due to its larger size. They do not breed with the other species on the island, as the females do not recognize the songs of the new males. Genetic evidence shows that currently, after several generations (a time scale that suggests shorter speciation events could have occurred previously),[30] it lives in a complete reproductive isolation from the native species.[31][32][33][34] According to professor Leif Andersson of Uppsala University, a taxonomist not aware of its history would consider it a distinct species.[35][36]

- Genus Camarhynchus

- Large tree finch (Camarhynchus psittacula)

- Medium tree finch (Camarhynchus pauper)

- Small tree finch (Camarhynchus parvulus)

- Woodpecker finch (Camarhynchus pallidus) – sometimes separated in Cactospiza

- Mangrove finch (Camarhynchus heliobates)

- Genus Certhidea

- Green warbler-finch (Certhidea olivacea)

- Grey warbler-finch (Certhidea fusca)

- Genus Pinaroloxias

- Cocos finch (Pinaroloxias inornata)

- Genus Platyspiza

- Vegetarian finch (Platyspiza crassirostris)

Modern research

[edit]A long-term study carried out for more than 40 years by the Princeton University researchers Peter and Rosemary Grant has documented evolutionary changes in beak size affected by El Niño/La Niña cycles in the Pacific.[37]

Molecular basis of beak evolution

[edit]Developmental research in 2004 found that bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), and its differential expression during development, resulted in variation of beak size and shape among finches. BMP4 acts in the developing embryo to lay down skeletal features, including making the beak stronger.[38] The same group showed that the development of the different beak shapes in Darwin's finches are also influenced by slightly different timing and spatial expressions of a gene called calmodulin (CaM).[39] Calmodulin acts in a similar way to BMP4, affecting some of the features of beak growth like making them long and pointy. The authors suggest that changes in the temporal and spatial expression of these two factors are possible developmental controls of beak morphology. In a recent study genome sequencing revealed a 240 kilobase haplotype encompassing the ALX1 gene that encodes a transcription factor affecting craniofacial development is strongly associated with beak shape diversity.[40][41] Moreover, these changes in the beak size have also altered vocalizations in Darwin's finches.[5]

Further research from 2016, in which genomes from each of the Darwin's finch species were sequenced, established that a single nucleotide polymorphism in the high mobility AT-hook 2 gene (HMGA2) locus is significantly associated with variation in beak size (Lamichhaney et al. 2016). HMGA2 codes for a transcription factor which in humans has been associated with variation in height, craniofacial distances, and primary tooth eruption.

In an analysis of the genomes of individuals from three Geospiza ground finch species found in sympatry (G. fortis, G. fuliginosa, G. magnirostris), 11 out of 32,569 SNPs were identified as representing four independent groups of statistically linked SNPs that together explained 83.6% of the variance in beak size (Chaves 2016). What this means is that only a small fraction of the genome in Darwin's finches is responsible for variation in beak morphology which is consistent with the rapid changes in beak form in response to the varying environments on the Galapagos Islands.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Grant & Grant 2008, p. 3

- ^ Marsh, Geoff (11 February 2015). "Darwin's iconic finches join genome club". Nature. 518 (7538): 147. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..147M. doi:10.1038/518147a. PMID 25673391.

- ^ Koffmar, Linda (12 February 2015). "Evolution of Darwin's finches and their beaks". Uppsala University, Sweden. Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ Soons, Joris; Herrel, Anthony; Genbrugge, Annelies; Aerts, Peter; Podos, Jeffrey; Adriaens, Dominique; Witte, Yoni de; Jacobs, Patric; Dirckx, Joris (12 April 2010). "Mechanical stress, fracture risk and beak evolution in Darwin's ground finches (Geospiza)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1543): 1093–1098. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0280. PMC 2830229. PMID 20194171.

- ^ a b c Podos, Jeffrey; Nowiki, Stephen (2004). "Beaks, Adaptation, and Vocal Evolution in Darwin's Finches". BioScience. 54 (6): 501–510. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0501:baavei]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Sato A, Tichy H, O'hUigin C, Grant PR, Grant BR, Klein J (March 2001). "On the Origin of Darwin's Finches". Mol. Biol. Evol. 18 (3): 299–311. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003806. PMID 11230531.

- ^ Lack, David (1947). Darwin's Finches. Cambridge University Press. Reissued in 1961 by Harper, New York. Reissued in 1983 by Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-25243-1.

- ^ Steinheimer 2004, p. 300

- ^ For Darwin's finches, beak shape goes beyond evolution Leah Burrows, Harvard University: News and Events. November 12, 2021

- ^ a b Grant, K. Thalia; Estes, Gregory B. (2009). Darwin in Galapagos: Footsteps to a New World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Steinheimer 2004, pp. 301–303

- ^ Keynes 2000, p. xix.; Eldredge 2006

- ^ Chancellor, Gordon; Keynes, Randal (October 2006), Darwin's field notes on the Galapagos: 'A little world within itself', Darwin Online, archived from the original on 2011-08-21

- ^ Eldredge 2006

- ^ Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 208–209

- ^ a b c Sulloway 1982, pp. 57–58

- ^ Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 248

- ^ Sulloway 2006

- ^ Darwin 1839, pp. 461–462

- ^ Darwin 1839, p. 462.

- ^ Darwin 1845, pp. 379–380

- ^ Darwin 1887

- ^ Darwin 1845, p. 380.

- ^ Darwin 1859, pp. 397–398.

- ^ Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R. (1989). Evolutionary dynamics of a natural population: the large cactus finch of the Galápagos. Chicago. p. 241 first para. ISBN 978-0226305905.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Grant 1999, p. 428 in Afterword.

- ^ John Maynard Smith (1998). "Chapter 5". Evolutionary genetics (2nd ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0198502319.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Grant 1999, plate 7.

- ^ Sulloway 1982, pp. 50

- ^ Strange Galapagos "Big Bird" reveals outcome of super-fast evolution Peter Hess, Inverse. November 27th, 2017

- ^ Holmes, Bob (10 February 2022). "Learning about birds from their genomes". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-021022-1. S2CID 246769765. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ Galloway, Rory (23 November 2017). "Galapagos finches caught in act of becoming new species". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- ^ Lamichhaney, Sangeet; Berglund, Jonas; Almén, Markus Sällman; Maqbool, Khurram; Grabherr, Manfred; Martinez-Barrio, Alvaro; Promerová, Marta; Rubin, Carl-Johan; Wang, Chao; Zamani, Neda; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R.; Webster, Matthew T.; Andersson, Leif (February 2015). "Evolution of Darwin's finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing". Nature. 518 (7539): 371–375. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..371L. doi:10.1038/nature14181. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25686609. S2CID 4462253. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- ^ Lamichhaney, Sangeet; Han, Fan; Webster, Matthew T.; Andersson, Leif; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R. (12 January 2018). "Rapid hybrid speciation in Darwin's finches". Science. 359 (6372): 224–228. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..224L. doi:10.1126/science.aao4593. PMID 29170277. S2CID 206663426.

- ^ Galloway, Rory (23 November 2017). "Galapagos finches caught in act of becoming new species". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2017-11-30.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (24 November 2017). "A New Bird Species Has Evolved on Galapagos And Scientists Watched It Happen". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 2017-12-09.

- ^ Lewitt, Dan. "Galapagos Finch Evolution – Dan Lewitt – HHMI (2013)". Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Abzhanov, Arhat; Protas, Meredith; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R.; Tabin, Clifford J. (3 September 2004). "Bmp4 and Morphological Variation of Beaks in Darwin's Finches". Science. 305 (5689): 1462–1465. Bibcode:2004Sci...305.1462A. doi:10.1126/science.1098095. ISSN 0036-8075. OCLC 1644869. PMID 15353802. S2CID 17226774.

- ^ Abzhanov, Arhat; Kuo, Winston P.; Hartmann, Christine; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R.; Tabin, Clifford J. (3 August 2006). "The calmodulin pathway and evolution of elongated beak morphology in Darwin's finches". Nature. 442 (7102): 563–567. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..563A. doi:10.1038/nature04843. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 1586310. PMID 16885984. S2CID 2416057.

- ^ Andersson, Leif; Lamichhaney, Sangeet; Berglund, Jonas; Almén, Markus Sällman; Maqbool, Khurram; Grabherr, Manfred; et al. (11 February 2015), "Evolution of Darwin's finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing", Nature, 518 (7539): 371–5, Bibcode:2015Natur.518..371L, doi:10.1038/nature14181, ISSN 0028-0836, OCLC 1586310, PMID 25686609, S2CID 4462253

- ^ Kaplan, Sarah (22 April 2016). "200 years after Darwin, this is how the iconic Galapagos finches are still evolving". Speaking of Science. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31.

References

[edit]- Darwin, Charles (1839), Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Journal and remarks. 1832–1836, vol. III, London: Henry Colburn

- Darwin, Charles (1845), Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N (2nd. ed.), London: John Murray

- Darwin, Charles (1859), On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.), London: John Murray

- Darwin, Francis (1887), "Chapter 1, The Foundations of the 'Origin of Species'", in Darwin, Francis (ed.), The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter, vol. 2, London: John Murray

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991), Darwin, London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group, ISBN 978-0-7181-3430-3, OCLC 185764721

- Eldredge, Niles (2006), "Confessions of a Darwinist", The Virginia Quarterly Review, no. Spring 2006, pp. 32–53, retrieved 2008-11-04

- Grant, Peter R. (1999), Ecology and evolution of Darwin's finches, Princeton, NJ

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grant, Peter R.; Grant, B. Rosemary (2008), How and Why Species Multiply: The Radiation of Darwin's Finches, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13360-7

- Lack, David (1940), "Evolution of the Galapagos Finches", Nature, vol. 146, no. 3697 (published 7 September 1940), pp. 324–327, Bibcode:1940Natur.146..324L, doi:10.1038/146324a0, S2CID 43465549

- Check-list of North American Birds, American Ornithologists' Union, 1998–2006, archived from the original on 2007-04-04, retrieved 2007-04-09

- Burns, Kevin J.; Skutch, Alexander F. (2003), "Tanagers and Tanager-Finches", in Christopher Perrins (ed.), The Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds, Firefly Books, pp. 629–631, ISBN 978-1-55297-777-4 It is not clear whether this placement was made by Burns and Skutch or by Perrins.

- Keynes, Richard (2000), Charles Darwin's zoology notes & specimen lists from H.M.S. Beagle, Cambridge University Press, retrieved 2008-12-08

- Sibley, Charles G. (1993), A World Checklist of Birds, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-07083-5, retrieved 2013-12-06 Monroe and Sibley consider the tanagers to be a tribe (Thraupini) of a big family Fringillidae rather than a family of their own (Thraupidae).

- Zimmer, J. (5 April 2007), A classification of the bird species of South America, American Ornithologists' Union, archived from the original on 2009-03-02, retrieved 2007-04-09

- Steinheimer, F. D. (2004), "Charles Darwin's bird collection and ornithological knowledge during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, 1831–1836", Journal of Ornithology, vol. 145, no. 4, pp. 300–320, doi:10.1007/s10336-004-0043-8, S2CID 24957761, retrieved 2008-12-08

- Sulloway, Frank J. (1982), "The Beagle collections of Darwin's finches (Geospizinae)", Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Historical Series, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 49–94, retrieved 2008-12-08

- Sulloway, Frank J. (2006), "Why Darwin Rejected Intelligent Design" (PDF), in Brockman, John (ed.), Intelligent Thought: Science versus the Intelligent Design Movement, New York: Vintage, pp. 107–126

- Lamichhaney, S., F. Han, J. Berglund, C. Wang, M. S. Almén, M. T. Webster, B. R. Grant, et al. 2016. A beak size locus in Darwin’s finches facilitated character displacement during a drought. Science 352:470–474.

- Chaves, J. A., E. A. Cooper, A. P. Hendry, J. Podos, L. F. De León, J. A. M. Raeymaekers, W. O. MacMillan, et al. 2016. Genomic variation at the tips of the adaptive radiation of Darwin’s finches. Molecular Ecology 25:5282–5295.

Further reading

[edit]- Grant, K. T.; Estes, G. B. (2009), Darwin in Galapagos: Footsteps to a New World, Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Sulloway, Frank J. (Spring 1982), "Darwin and His Finches: The Evolution of a Legend" (PDF), Journal of the History of Biology, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–53, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.458.3975, doi:10.1007/BF00132004, S2CID 17161535, retrieved 2008-12-09

External links

[edit]- Different bills and song melodies

- Genetics and the Origin of Birds Species, Grant and Grant in PNAS

- Sato et al. Phylogeny of Darwin's finches as revealed by mtDNA sequences in PNAS

- Galápagos Online. Darwin's Finches.

- Galapagos Online. List of birds of the Galapagos Islands.

- Darwin's Finches Evolve Before Scientists' Eyes: new developments reported 13 July 2006

- Fink F.A.Q. Darwin's finches inspired the naming of the Fink project, a collaborative initiative for porting open source software to the Darwin platform to enable its use and evolution in the Apple Mac OS X environment. "Fink" is the German name for "finch."

- Aug 2006 Nature Article that shows how modulation of a certain gene during development can account for the differences seen in beak shape.

- Speciation Kimball's Biology Pages