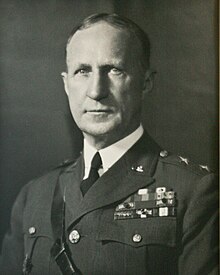

George Van Horn Moseley

George Van Horn Moseley | |

|---|---|

Major General George Van Horn Moseley | |

| Born | September 28, 1874 Evanston, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | November 7, 1960 (aged 86) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1899–1938 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Service number | 0-772 |

| Commands | Third United States Army 4th Corps Area 5th Corps Area Deputy Chief of Staff of the United States Army 1st Cavalry Division |

| Battles / wars | Spanish–American War Pancho Villa Expedition World War I |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal (2) Commander of the Legion of Honor (France) Croix de guerre (France) Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) Commander of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Commander of the Order of the Crown of Italy |

George Van Horn Moseley (September 28, 1874 – November 7, 1960) was a United States Army general. Following his retirement in 1938, he became controversial for his fiercely anti-immigrant and antisemitic views.

A native of Evanston, Illinois, Moseley was an 1899 graduate of the United States Military Academy (West Point). Initially assigned to the Cavalry, he later transferred to the Field Artillery. He was an aide-de-camp to Brigadier General Jesse M. Lee during the Philippine–American War, and later commanded troops during an expedition against the Pulahan on Samar and Leyte. As he continued to advance in rank and responsibility, Moseley graduated from the United States Army Command and General Staff College in 1908 and the United States Army War College in 1911.

During World War I, Moseley was promoted to temporary brigadier general as chief of staff for the 7th Division, and was later assigned as assistant chief of staff for logistics (G-4) on the staff of the American Expeditionary Forces. After the war, Moseley remained in Europe to take part in the Occupation of the Rhineland. In 1919, he was appointed to the Harbord Commission, which reviewed relations between the United States and Armenia and provided policy recommendations to the U.S. government. He was promoted to permanent brigadier general in 1921, and he commanded the 1st Cavalry Division from 1927 to 1929. Moseley was subsequently promoted to major general, and he served as the army's deputy chief of staff (1931–1933), and successively commanded Fifth Corps Area, Fourth Corps Area, and Third United States Army before retiring in 1938.

After retiring, Moseley became a prominent critic of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, and his arguments included strident anti-communism and antisemitism, as well as opposition to immigration and support for fascism and Nazism. He continued to argue against the New Deal even after Roosevelt's death, and remained involved with rightwing causes until his death. Moseley died in Atlanta on November 7, 1960, and was buried at West Point Cemetery.

When American Nazi sympathizer George E. Deatherage plotted to launch a coup in the 1930s, he sought to recruit Moseley as a potential military dictator.[1]

Early life and career

[edit]

Moseley was born in Evanston, Illinois, on September 28, 1874.[2] He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1899 and was commissioned second lieutenant in the cavalry. He served in the Philippines twice, from 1900 to 1903 and 1906 to 1907, where his assignments included commanding a troop of the 1st Cavalry and serving as aide-de-camp to Generals J. M. Bell and J. M. Lee. In 1901 Moseley, accompanied by only one other officer, without escort and under conditions of great danger, penetrated a major Philippine insurgent stronghold. 2nd Lt. Moseley and 1st Lt. George Curry convinced Brigadier General Ludovico Arejola to sign the peace agreement in Taban, Minalabac (Philippines) on March 25, 1901.

The honor graduate of the Army School of the Line in 1908, Moseley also graduated from the Army Staff College in 1909 and the Army War College in 1911. During World War I, Moseley served as assistant chief of staff for logistics (G-4) on the staff of the American Expeditionary Force headquarters.

Moseley married Mrs. Florence DuBois in July 1930.[3]

Moseley held camp and Washington assignments from 1920 to 1929. He was a member of several important commissions, including the Harbord Commission to investigate Armenian issues. After commanding the Second Field Artillery Brigade, in 1921 he was detailed as assistant to General Dawes in organizing the newly created Bureau of the Budget. In 1921 he was promoted brigadier general, Regular Army. Commanding the 1st Cavalry Division (1927–1929), he successfully interceded, under fire, with principals in a 1929 Mexican insurrection. His actions stopped stray gunfire from Juarez, Mexico, from endangering life and property in adjacent El Paso, Texas, and precluded further incidents. In 1931 he was promoted major general, Regular Army.

Senior assignments

[edit]Moseley was the executive for the Assistant Secretary of War, from 1929 to 1930 and Deputy Chief of Staff of Army from 1930 to 1933.[4] He served as General Douglas MacArthur's Deputy Chief of Staff during the 1932 Bonus March on Washington, D.C., in the course of which he recorded his fears of a Communist conspiracy against the United States and his identification of Jews with radicals and undesirables. He wrote in a private letter:[5]

We pay great attention to the breeding of our hogs, our dogs, our horses, and our cattle, but we are just beginning to realize the ... effects of absorbing objectionable blood in our breed of human beings. The pages of history give us the tragic stories of one-time leading nations which ... imported manpower of an inferior kind and then ... intermarried with this inferior stock. ... Those nations have either passed out of separate existence entirely, or have remained as decadent entities without influence in world affairs.

In 1934, Moseley asked MacArthur to consider the immigration issue in terms of military manpower, contrasting a group of "southern lads" of "good Anglo-Saxon stock" with their counterparts from the North with names "difficult to pronounce" that "indicated foreign blood". Moseley linked the latter to labor problems and "so much trouble in our schools and colleges." MacArthur expressed skepticism in response to Moseley's argument that "It is a question of whether or not the old blood that built this fine nation ... is to continue to administer that nation, or whether that old stock is going to be destroyed or bred out by a lot of foreign blood which the melting pot has not touched."[6]

Moseley was commanding general of the 5th Corps Area, from 1933 to 1934 and 4th Corps Area from 1934 to 1936. His final assignment was as commander of the Third United States Army from 1936 to 1938.

Controversy

[edit]While still on active service, Moseley expressed controversial opinions in public. In 1936, he proposed that the Civilian Conservation Corps be expanded "to take in every 18-year-old youth in the country for a six-month course in work, education and military training."[7] In the late 1930s, when admitting refugees from Nazi persecution was a matter of national controversy, Moseley supported admitting refugees but added the proviso "that they all be sterilized before being permitted to embark. Only that way can we properly protect our future."[8]

Retirement

[edit]Moseley retired from the Army in October 1938 with a statement that described the New Deal as a growing dictatorship: "We do not have to vote for a dictatorship to have one in America ... We have merely to vote increased government responsibility for our individual lives, increased government authority over our daily habits, and the resultant Federal paternalism will inevitably become dictatorship." Secretary of War Harry Woodring called his statement "flagrantly disloyal."[9] In April 1939 he attacked Jews and said that he foresaw a war fought for their benefit. He attacked President Franklin D. Roosevelt for appointing Felix Frankfurter to the U.S. Supreme Court. He predicted that the U.S. Army would not follow the orders of FDR's leftist administration if they "violate all American tradition." He described fascism and Nazism as good "antitoxins" for the United States, adding that "the finest type of Americanism can breed under their protection as they neutralize the efforts of the Communists."[10] Moseley understood that as a retired general, he remained subject to the War Department's jurisdiction, writing to a friend: "The only good I can do now is in keeping up quite a large correspondence with men who are in a position to influence public affairs. The enemy has completely silenced me, and I am handicapped, as I am still a Government official."[11] Moseley also tried to lobby the New York National Guard adjutant to "cleanse" the state forces of all Jews and persons of color.[11]

When American Nazi sympathizer George E. Deatherage plotted to launch a coup in the 1930s, he sought to recruit Moseley as a potential military dictator.[1]

Time reported his view that "more money should be spent on syphilis prevention and less on national defense".[9] Two months after leaving the military, he questioned the President's proposed increases in military spending: "Much of our present weakness is in the fear and hysteria being engendered among the American people for ... political purpose. ... A nation so scared and so burdened financially is not in a condition to lick anybody. And then, who in hell are we afraid of? With Japan absorbed ... with the balance of power so nearly equal in Europe, where is there an ounce of naval or military strength free to threaten us?"[12] He became increasingly more outspoken and instead of the language of Social Darwinism expressed anti-Semitic and conspiratorial views overtly. In Philadelphia, he told the National Defense Meeting that Jewish bankers had financed the Russian Revolution and that "The war now proposed is for the purposes of establishing Jewish hegemony throughout the world." He said that Jews controlled the media and might soon control the federal government.[13]

In June 1939, Moseley testified for five hours before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He said that a Jewish Communist conspiracy was about to seize control of the U.S. government. He believed the President had the authority to counteract the planned coup and could do so "in five minutes" by issuing an order "to discharge every Communist in the government and everyone giving aid and comfort to the Communists." He said the President could use the Army against "the enemy within our gates" but did not seem willing to do so. He said he held no anti-Semitic views and that "the Jew is an internationalist first ... and a patriot second." He praised the "impressively patriotic" German-American Bund and said its purpose was to "see that Communists don't take over the country." Among Moseley's supporters who attended the hearing were Donald Shea, head of the American Gentile League and James True of America First Inc.[14] The Committee found a prepared statement he read into the record so objectionable it was deleted from the public record.[15][16] A few days later, Thomas E. Stone, head of the Council of United States Veterans, accused Moseley of treason and wrote that his praise of the Bund "abets a foreign government in the preparation of disruption against the eventuality of possible future hostilities, and that this he is acting in treason to our national safety."[17]

Moseley held anti-immigrant views throughout his life. In his unpublished autobiography, he quoted approvingly from Madison Grant's The Passing of the Great Race.[18] He used the language of Social Darwinism to describe the problem the United States faced:[19]

Watch a herd of animals. If a member of the herd becomes unfit ... the unfortunate is recognized at once and driven out of the herd, only to be eaten by the timber wolves. That seems hard–but is it, in fact? The suffering is thus limited to the one. The disease is not allowed to attack the others. ... With us humans, what we call civilization compels us to carry along the unfit in ever increasing proportions.

Moseley described the Jew as a permanent "human outcast." They were "crude and unclean, animal-like things ... something loathsome, such as syphilis."[16] Following the Nazi invasion of France, he wrote that, in order to match the Nazi threat, the U.S. needed to launch a program of "selective breeding, sterilization, the elimination of the unfit, and the elimination of those types which are inimical to the general welfare of the nation."[13] In December 1941, Moseley wrote that Europe's Jews were "receiving their just punishment for the crucifixion of Christ ... whom they are still crucifying at every turn of the road." He proposed a "worldwide policy which will result in bleeding all Jewish blood out of the human race."[16]

Shortly after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, Moseley wrote to former president Herbert Hoover, alleging that a conspiracy of the British government and Jews in the United States goaded Japan to make war on the United States.[20]

In 1947, Moseley said of his years as a West Point cadet, "there was one Jew in my class, a very undesirable creature, who was soon eliminated."[21] In the 1950s, he became a critic of the Eisenhower Administration and championed the rehabilitation of convicted Nazi war criminal Karl Doenitz.[22]

In 1951, the president of Piedmont College in Georgia invited Moseley to speak. Students and faculty protested because of his racist views. TIME called him a "trumpeter for Aryan supremacy." One faculty member was fired for speaking in opposition to the speaking engagement.[23] Calls for the president's resignation followed.[24] Almost the entire faculty and nine trustees resigned over the next two years, and enrollment fell by two-thirds.[25]

In 1959, Moseley was one of the founders of Americans for Constitutional Action, an anti-Semitic successor to America First.[26]

In retirement, Moseley lived at the Atlanta Biltmore Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia. He died in Atlanta from a heart attack on November 7, 1960, and was buried at West Point Cemetery.[2] Although he had disappeared from the public's view, he continued to influence a generation of other officers, including Albert Wedemeyer, who shared similar beliefs.

Awards

[edit]Moseley's awards included the Army Distinguished Service Medal (one oak leaf cluster); Commander of the Order of the Crown (Belgium); Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom); Commander of the Legion of Honor and Croix de Guerre with Palm (France); and Commander of the Order of the Crown of Italy. He was also a recipient of the Philippine Campaign Medal, Mexican Service Medal and the World War I Victory Medal.

Family

[edit]Moseley had three sons. He married Alice Dodds in 1902 and married Florence DuBois in July 1930.[3] Alice was mother to George & Francis, Florence was mother to James.

- Colonel George Van Horn Moseley Jr. led the 502d Parachute Infantry Regiment into Normandy in 1944.

- Francis L. Moseley was an inventor and Vice President at the Hewlett-Packard Company.

- James W. Moseley was a longstanding figure in the UFO enthusiast community.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "A Look Back". Mountain Messenger. November 4, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "U.S. Racist Leader Dies". Springfield Leader and Press. Atlanta. AP. November 8, 1960. p. 13. Retrieved January 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b TIME ""Milestones, July 7, 1930"". Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ Weintraub, 12

- ^ Bendersky, 202–203

- ^ Bendersky, 216

- ^ TIME: ""Conservation: Poor Young Men," February 6, 1939". Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ Bendersky 250

- ^ a b TIME: ""Moseley's Day Off," October 10, 1938". Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ TIME: ""National Affairs: Moseley Roars", April 10, 1939". Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2010., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ a b Kastenberg 594, 610

- ^ TIME ""National Affairs: Rearmament v. Balderdash," December 19, 1938". Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ a b Bendersky, 255

- ^ The New York Times: "Moseley Proposes Use of the Army to Drive out Reds," June 1, 1939, accessed April 4, 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ The New York Times: "The News of the Week in Review," June 4, 1939, accessed April 4, 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Bendersky, 256

- ^ The New York Times: "Treason' Charged by Moseley Critic," June 7, 1939, accessed April 4, 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ Bendersky, 26

- ^ Bendersky, 27

- ^ Kastenberg 610

- ^ Bendersky, 38

- ^ Kastenberg 611

- ^ TIME: ""Education: Give It Back", March 12, 1951". Archived from the original on February 11, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ TIME: ""Education: Piedmont Uprising", April 2, 1951". Archived from the original on February 11, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ TIME: ""Education: For Outstanding Services", June 29, 1953". Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2011., accessed January 7, 2023

- ^ Bendersky, 410

Sources

[edit]- Bendersky, Joseph W., The Jewish Threat (Basic Books, 2002)

- James, D. Clayton, The Years of MacArthur, vol. 1: 1880–1941 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970)

- Smith, Richard Norton, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1981, ISBN 978-0-9623-3331-6)

- Weintraub, Stanley, 15 Stars: Eisenhower, MacArthur, Marshall, Three Generals Who Saved the American Century (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007, ISBN 0-7432-7527-6)

- Kastenberg, Joshua E., "The Crisis of June 2020: The Case of the Retired General and Admirals and the Clarion Calls of their Critics in Lex Non Scripta (Historic) Perspective", 99 University of Nebraska Law Review, 594, 610 (2021)

- Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, North Carolina: Pentland Press. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

- Venzon, Anne Cipriano (2013). The United States in the First World War: an Encyclopedia. Hoboken, NJ: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-68453-2. OCLC 865332376.

External links

[edit]- United States Third Army biography Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- George Van Horn Moseley papers at Library of Congress

- 1874 births

- 1960 deaths

- American anti–World War II activists

- American conspiracy theorists

- American Nazis

- American neo-Nazis

- American nationalists

- American segregationists

- Christian fascists

- Commanders of the Order of the Crown (Belgium)

- Military personnel from Evanston, Illinois

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- United States Army generals of World War I

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- United States Army War College alumni

- Burials at West Point Cemetery

- 19th-century United States Army personnel