George T. Downing

George T. Downing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 30, 1819 New York City, US |

| Died | July 21, 1903 (aged 83) |

| Resting place | Island Cemetery, Newport, Rhode Island |

| Alma mater | Hamilton College |

| Occupation(s) | Abolitionist, entrepreneur, restaurateur, caterer |

| Political party | Republican |

George T. Downing (December 30, 1819 – July 21, 1903) was an abolitionist and activist for African-American civil rights while building a successful career as a restaurateur in New York City; Newport, Rhode Island; and Washington, D.C. His father had been an oyster seller and caterer in Philadelphia and New York City, building a business that attracted wealthy white clients. From the 1830s until the end of slavery, Downing was active in the Underground Railroad, using his restaurant as a rest station for refugees on the move. He built a summer season business in Newport, and made it his home. For more than 10 years, he worked to integrate Rhode Island public schools. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Downing helped recruit African-American soldiers.

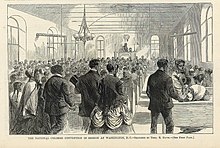

After the war Downing moved to Washington, D.C., where for a dozen years he ran the Refectory for the House of Representatives. He was a prominent member in the Colored Conventions Movement and worked to join the efforts of women's rights and black rights. He became close to senator Charles Sumner and was with the legislator when he died. Late in his life he returned to Rhode Island, where he continued as a community leader and civil rights activist.

Early life

[edit]George Thomas Downing was born in New York City on December 30, 1819, to Thomas Downing and Rebecca (West). His father Thomas was born in 1791 in Chincoteague, Virginia, to parents who had been freed from slavery when their master, John Downing, a prominent planter, converted to Methodism. The couple took his surname and were also Methodists. The local Methodist congregation named their meeting house in Oak Hill after Downing because of his acts. Downing hired Thomas' parents to serve as caretakers at the meeting house, and provided a tutor for Thomas. Thomas grew up learning about refined tastes from guests hosted by John Downing at his own house, near the land his parents were given.[1] His son George, having heard accounts from his successful father in New York, later described these guests as the leading families of Virginia.[2]

Thomas Downing left Virginia as a young man and went north to Philadelphia, where he met and married Rebecca West, a free black. He worked for a time at an oyster bar. By 1819 they had moved to New York. The couple had five children: George, twins Thomas and Henry, Jane, and Peter William.[2]

The senior Downing at first cultivated oyster beds in the Jersey flats, but by 1825 he purchased an eating establishment in the basement at 5 Broad Street in Manhattan. He gradually expanded into other spaces on that block, and developed a refined oyster house with dishes to appeal to the powerful white men of business and finance in that area of the city.[1] Over time, his business attracted notable foreign visitors, including Charles Dickens and Lord Morpeth.[3] Downing was known to have sent some American oysters to Queen Victoria, in recognition of which she sent a gold chronometer watch to Thomas in the care of Commodore Joseph Comstock.[3][1] The Downing family attended St. Philip's Episcopal Church, the first African-American Episcopal church in the city. Thomas became one of its wealthiest members; it was a center for men and families who were ambitious and hardworking.[1] Thomas died on April 10, 1866, several years after his wife Rebecca.[4]

The parents stressed education for advancement, and Downing and his twin brothers, Thomas and Henry, were educated in New York City, while the younger Peter studied for several years in Paris. Their sister died while young.[4] Henry's son, Henry Francis Downing, became a noted sailor, consul, author, and playwright.[5]

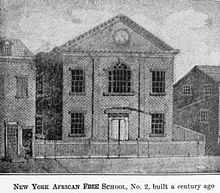

The first school George attended was held by Charles Smith on Orange Street; he next studied at Mulberry Street School, also known as the African Free School. As a child, Downing was known to lead other black students to chase off whites who harassed them.[6] His father's prominence in New York afforded George many unique experiences; for instance, he met Lafayette when the patriot toured the states during Downing's boyhood. When he was 14, Downing organized a literary society of his peers; their discussion topics included resolving to refrain from celebrating the Fourth of July as a holiday and why the Declaration of Independence should not be celebrated by blacks; it was a mockery until they had achieved legal equality in the United States.[4] Classmates involved in the society included Philip Bell, Alexander Crummell, James McCune Smith, and Henry Highland Garnet, all of whom became leaders as adults.[7] Also as a youth, Downing began to work as an agent for the Underground Railroad. Among his first works was to help "Little Henry", a slave who was jailed in New York.[8] Downing attended Hamilton College in upstate New York.

Family

[edit]On November 24, 1841, Downing married Serena Leanora de Grasse. Serena had attended Clinton Seminary in Oneida County, New York, and was friends with the daughter of Gerrit Smith, through whom she met Downing. Her father was George de Grasse, born in Calcutta, India, about 1780 and originally named Azar Le Guen. He is believed to have been the natural, mixed-race son of François Joseph Paul de Grasse, a career French naval officer who was in the city intermittently, and an Indian woman.[9] De Grasse took Azar back to Paris for his education and adopted him, naming him George de Grasse.[9] The senior de Grasse was promoted to admiral in 1781, and commanding the French fleet in the west, was a naval hero of the American Revolution, conducting a blockade in the Chesapeake Bay that led to the British surrender in 1781 at Yorktown.[10]

By 1799, George de Grasse had immigrated from France and settled in New York City, where in 1804 he became a naturalized citizen. He had worked for Aaron Burr, likely through connections of his father, who gave him two lots of land.[9] In New York, de Grasse met and married Maria van Surley (also known as van Salee) of New York. She was the daughter of John and Margaret van Surley (the surname was also recorded as Van Salee). Her mother was a German immigrant, and John was a veteran of the Revolution. His immigrant ancestor was Abraham Janzsoon van Salee, an early Moorish-Dutch settler in New Amsterdam about 1630.

George and Maria stressed education for all three of their children. Serena's eldest brother was Isaiah DeGrasse, who graduated from Newark College (now the University of Delaware) and became a Protestant Episcopal minister. Her second brother was John van Salee de Grasse, who was educated in Paris[10] and at Bowdoin College's medical school; he was the first man of color (African American) to gain a medical degree in the United States.

Downing and Serena had the following children: Serena Anne Miller, George Isaiah, Thomas, Cordelia, Irene Dow, Rebecca Medora, Mary, Georgenia Frances, Philip Bell, and Peter John.[11]

Catering career

[edit]In 1842, Downing started his own catering business on Fourth and Broadway, moving in 1845 to 690 Broadway. His work brought him in touch with many of the elite of the city, including the Astors, Kernochans, leRoys, Schermahorns, and Kennedys. His success allowed him to establish a summer business in Newport, Rhode Island. He moved in 1848 to Catherine and Fir streets, and in 1850 to State Street and what was later named in his honor as Downing Street.

In 1849 Downing purchased a Bellevue Avenue estate in Newport from Charles Sherman. In 1850 he moved to Providence, Rhode Island, continuing to work in Newport during the summer. In 1854 he built the Sea Girt Hotel, which burned to the ground on December 15, 1860, after suspected arson. He replaced the building with Downing Block, part of which he rented to the government to serve as a hospital for the Naval Academy, which was temporarily operating in Newport at the Naval Station.

After the Civil War, in 1865 Downing moved to Washington, D.C., encouraged by US Representative Nathan F. Dixon II. He managed the House Refectory for twelve years. In 1877 he moved back to Newport, where he retired in 1879.[12]

In the early days of the New York Herald, Downing's father had loaned money to James Gordon Bennett, Sr., helping him keep the paper afloat. To some degree in return, the paper supported Downing's business and politics during Bennett's life and that of his son, James Gordon Bennett, Jr.,[13]

Civil rights and community leadership

[edit]Anti-slavery activism

[edit]

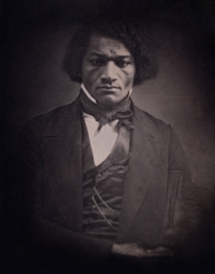

Downing was an important leader in abolitionism in New York. He was active in the organization of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833.[14] Together with Frederick Douglass and Alexander Crummell, Downing was a noted opponent of the American Colonization Society in the 1830s and 1840s; it proposed to relocate free American blacks to the colony of Liberia in West Africa. Downing and his allies argued instead for equal rights for blacks in the United States.[15] In 1841 Downing was beaten by agents of the Harlem Railroad for attempting to ride the train.[16]

In 1847 he began working for equal education for black children. That year he became a member of the first board of trustees of the New York Society for the Promotion of Education of Colored Children.[17] As he became more involved in life in Rhode Island, he also started working to achieve integration in its public schools.

In June 1850, Downing together with Frederick Douglass, Samuel Ward, Lewis Woodson, and others formed the American League of Colored Laborers as a union to organize former slaves working in New York City.[18] He was also a member of the Committee of Thirteen, which resisted the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 and aided refugees from slavery pass through the city. His distaste for that bill was such that when he once met Millard Fillmore, he excused himself rather than shake the former president's hand, as he did not wish to touch the hand that signed that bill.[14] He was a member of the committee which greeted the arrival of Hungarian rebel leader Louis Kossuth to New York in 1851.[19]

In New York, Downing was an agent of the Underground Railroad, along with Isaac Hopper, Oliver Johnson, Charles B. Ray, David Ruggles, McCune Smith, James W. C. Pennington, and Henry Highland Garnet. Downing's station was run out of his Oyster House restaurant.[20]

Downing was also active in Rhode Island and New England. When fugitive slave Anthony Burns was imprisoned in Boston in 1854, prior to being shipped back to the South, Downing took part in the protests against his being forced back into slavery. He met with attorney Robert Morris to argue for Burns' cause.[21] Downing also pushed the Rhode Island legislature to integrate public schools, first financing a campaign of protest starting in 1857, which was finally successful in 1866.[22][23]

Civil War period

[edit]As the Civil War approached, Downing was central in the movement for African American civil rights. He was president of the Convention of Colored Citizens in Boston on August 1, 1859.[24] In 1860, Downing with J. S. Martin helped organize a meeting in Boston to celebrate the first anniversary of the death of abolitionist John Brown. The meeting was widely opposed by many in Boston, and the mayor attempted to dissuade Martin and Downing from holding the meeting. A mob gathered at Tremont Temple, and they were forced to adjourn. The next day they met at Joy Street Church, protected by the Boston police and militia. The meeting was highly visible, with Brown's son, John Brown, Jr., and Wendell Phillips making speeches.[25]

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Downing was encouraged to help enroll African Americans into the Union Army. He met with Massachusetts governor John Albion Andrew, and got from him written assurance that black troops would be treated with equality, upon which he took up the work.[26]

In October 1864, Downing was a prominent delegate to the Syracuse Colored Convention.[27] Over the previous decade, Downing had been a critic of nationalist-emigrationists such as Martin Delaney and Henry Highland Garnet. At the convention, this animosity came through. Frederick Douglass was chosen as president of the convention, and made some effort to keep the peace between factions which arose around Downing and Garnet.[28]

Reconstruction era

[edit]

In the second annual meeting of the American Equal Rights Association in 1867, Downing contrasted the issues of African-American and women's rights, asking whether those attending would be willing to support the vote for black men before women. While this tension doomed that organization,[29] the issue remained one of interest to Downing. At the National Convention of Colored Men in Washington, D.C., in January 1869, Downing was prominent in his support of women's rights.[30]

Downing had moved to Washington, D.C., at the war's end and became intimate with many politicians, particularly Senator Charles Sumner. Sumner quoted Downing in his argument for passage of the Civil Rights Bill in 1872, arguing for the right of citizens to have equal access to public facilities.[31] Downing was at Sumner's bedside with Sumner died in 1874.[32]

Downing and his family were directly involved in integration of Washington, D.C., society, opening the Senate gallery to blacks. They were the first blacks to occupy a box in a theater in the capital.[33] With the help of Sumner, he worked to integrate the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line between Washington and Baltimore.[34]

Downing played a role in Reconstruction politics as well. With the help of Horace Greeley, he led a delegation that met with president Andrew Johnson to push for the support of freedmen and free blacks against postwar violence and repression in the South. While organizing the delegation, he traveled throughout the South. On his way to New Orleans, he received a letter from the Ku Klux Klan which threatened his life.[32] Downing used his influence to help Edward Bassett gain an appointment as Minister Resident and Consul General for the United States to Haiti; it was the first appointment of a black man to a position in the Diplomatic Corps.[32]

In the late 1870s, Downing found himself opposing Frederick Douglass on an important issue. Together with John Mercer Langston and Richard T. Greener at meetings and conventions, Downing supported the cause of blacks migrating from the South to the North for more opportunities, especially as voter suppression of blacks increased in the South. Douglass thought Exodusters and others should stay in place and work to develop the area where they were born.[35]

Return to Rhode Island

[edit]Downing had long thought of Newport, Rhode Island as home. He continued to be politically active there. Downing was a Republican for much of his life, but he became more independent during the candidacy for president of James Blaine, whom he felt was soft on civil rights.[36] He supported a Democratic candidate for alderman of Newport; in exchange, the alderman arranged for the African American candidate, Mahlon Van Horne, to be elected to the school committee. Downing was active in attempting repeal of laws against racial inter-marriage in Rhode Island.[37]

Late in his life, Downing was given a commission as captain of a colored company of the Rhode Island militia. Downing refused the honor, protesting against the designation of the company as colored. The governor sent the commission again after deleting the discriminatory qualifier.[37] Also late in his life, Downing became an important benefactor to Newport. He was a large contributor to the purchase of the land which became Touro Park in the city, making the second-largest contribution after that of Judah Touro's estate. He also helped organize the politics behind the expansion of Newport's Bellevue Avenue. He declined an offer to be appointed as customs collector for the port of Newport.[37]

Other activities

[edit]He helped organize the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows and was Grand Master of the group for some years. He was also involved in freemasonry and was a Royal Arch Mason.[38]

Death and legacy

[edit]Downing died in Newport, Rhode Island on July 21, 1903,[39] and buried in Newport's Island Cemetery.[40] Obituaries were published in the Boston Globe, New York Times, and Cleveland Gazette (see below). The Boston Globe described him as "the foremost colored man in the country", praising his work for human liberty; it said in an editorial that "Narrowness was never safe where George T. Downing was present."[41]

In 2003 Downing was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bulthuis, Kyle T. (2014). Four Steeples over the City Streets: Religion and Society in New York's Early Republic Congregations. NYU Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 9781479807932 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Washington, S. A. M., George Thomas Downing: Sketch of His Life and Times, Newport, RI: Milne Printery (1910), p. 3

- ^ a b Washington (1910) p. 5

- ^ a b c Washington (1910) p. 6

- ^ Appiah, Anthony, and Henry Louis Gates Jr, eds. Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press, 2005. p. 444

- ^ Moses, Wilson Jeremiah. Alexander Crummell: A Study of Civilization and Discontent. Oxford University Press on Demand, 1989. p. 17

- ^ Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. pp. 995–1002

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 6–7

- ^ a b c P. Kanakamedala, "George DeGrasse a South Asian in Early African America", in India in the American Imaginary, 1780s–1880s, ed. by Anupama Arora & Rajender Kaur; Springer, 2017, pp. 228–243

- ^ a b Washington (1910) pp. 7–8

- ^ Washington (1910), pp. 21–22

- ^ Washington (1910) pp. 3–4, and 11

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 18

- ^ a b Washington (1910) p. 8

- ^ Moses (1989), p. 63

- ^ Hewitt, John H. Protest and Progress: New York's First Black Episcopal Church Fights Racism. Taylor & Francis, 2000. p. 88

- ^ Leslie Fishl, "George Thomas Downing", in Kwame Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 399–441

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations. Routledge, 2015. p. 168

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 9

- ^ Switala, William J. Underground Railroad in New Jersey and New York. Stackpole Books, 2006. p. 92

- ^ Washington (1910) pp. 9–10

- ^ Armstead, Myra Beth Young. Lord, Please Don't Take Me in August: African Americans in Newport and Saratoga Springs, 1870–1930. Vol. 82. University of Illinois Press, 1999. pp. 32–33

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 19

- ^ Brown, William Wells. Black Man. 1863. pp. 250–253

- ^ Washington (1910) pp. 9–11

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 11

- ^ Davis, Hugh. We Will be Satisfied with Nothing Less: The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North During Reconstruction. Cornell University Press, 2011. p. 2

- ^ Davis (2011), pp. 23–24

- ^ Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898. UNC Press Books, 2014. p. 19

- ^ Jones, Martha S. All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830–1900. Univ of North Carolina Press, 2009. p. 146

- ^ Washington (1910) pp. 10–15

- ^ a b c Washington (1910) p. 16

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 15

- ^ Washington (1910) pp. 15–16

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin. Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction. WW Norton & Company, 1992. p. 247

- ^ Washington (1910) pp. 18–19

- ^ a b c Washington (1910) p. 20

- ^ Washington 1910 p. 9

- ^ Washington (1910) p. 4

- ^ "Island Cemetery". RIP Newport. Newport, Rhode Island. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Boston Globe – 22, 23 July 1903

- ^ George T. Downing Archived 2017-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame

Sources

[edit]- Grossman, Lawrence. "George T. Downing and Desegregation in Rhode Island Public Schools, 1855–1866", Rhode Island History 36, 1977, pp. 99–105

- Hewitt, John H. "Mr. [Thomas] Downing and His Oyster House: The Life and Good Works of an African American Entrepreneur", New York History 74, 1993, pp. 229–252

- Protest and Progress: New York's First Black Episcopal Church Fights Racism Hewitt, John H. Protest and Progress: New York's First Black Episcopal Church Fights Racism], Taylor & Francis, 2000

- Washington, S. A. M. George Thomas Downing: Sketch of His Life and Times, Newport, RI: Milne Printery (1910); full text online at Internet Archive.

- Obituaries of G. T. Downing: New York Times, 22 July 1903; Boston Globe — 22, 23 July 1903; Cleveland Gazette, 1 August 1903

External links

[edit]- Davis, Paul (24 August 2013). "5 Rhode Islanders who laid the groundwork for later activists". Providence Journal. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2024.,

- 1819 births

- 1903 deaths

- People from New York (state)

- People from Newport, Rhode Island

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American abolitionists

- African-American feminists

- American feminists

- American restaurateurs

- Suffragists from New York (state)

- Underground Railroad people

- New York (state) Republicans

- Washington, D.C., Republicans

- Rhode Island Republicans

- African Free School alumni

- 19th-century American businesspeople

- 19th-century African-American businesspeople

- 20th-century African-American people

- 20th-century American women

- Suffragists from Rhode Island