George Sinclair (mathematician)

George Sinclair | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1630 |

| Died | 1696 |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | Mathematician

Engineer Professor |

| Years active | 17th Century |

| Academic background | |

| Education | University of St Andrews University of Edinburgh |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Maths

Geology Demonology |

| Notable works | Ars Nova et Magna Gravitatis et Levitatis (1669)

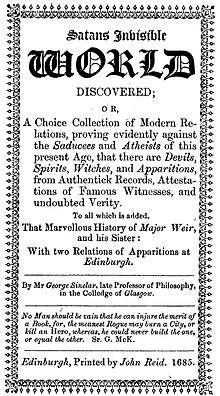

The Hydrostaticks (1672) Truth's Victory over Error (1684) Satan's Invisible World Discovered (1685) |

George Sinclair (Sinclar) (ca.1630–1696)[1][2] was a Scottish mathematician, engineer and demonologist. The first Professor of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow, he is known for Satan's Invisible World Discovered, (c. 1685), a work on witchcraft, ghosts and other supernatural phenomena. He wrote in all three areas of his interests, including an account of the "Glenluce Devil", a poltergeist case from c. 1654, in a 1672 book mainly on hydrostatics but also a pioneering study of geological structures through his experience in coal mines.

Life

[edit]Sinclair was most likely from the East Lothian area, around Haddington. He studied at the University of St Andrews between the years 1645 and 1646, but moved to complete his studies at the University of Edinburgh obtaining a Master of Arts degree from there in 1649.[2]

He became a professor at the University of Glasgow, on 18 April 1654, initially in a philosophy chair, then moved to a chair founded for mathematics. He helped to fund the building of Glasgow College in 1656.[3] In 1655 he made descents in a diving bell off the Isle of Mull, to look at the wreck of a ship from the Spanish Armada there.[4]

Being a Presbyterian, and failing to take the oath of allegiance, he was deprived of his university post in 1666.[5] He then worked as a mineral surveyor and engineer, and was employed in particular by Sir James Hope. He was brought in by the magistrates of Edinburgh, about 1670, to oversee piping of water from Comiston into the city.[6]

On 3 March 1691, University of Edinburgh appointed him again to the professorship of mathematics,[7] which had been newly re-funded after a long vacancy.[8]

Sinclair invented an early example of a perpetual motion machine based on the principle of the siphon. He first proposed this in a Latin work on pneumatics in 1669.[9]

Glenluce Devil

[edit]

In his book Satan's Invisible World Discovered (1685), Sinclair described an alleged poltergeist incident known as the Devil of Glenluce. Sinclair described the incident as having a "usefulness for refuting atheism."[10]

The incident is described as having taken place at the house of weaver Gilbert Campbell in Glenluce during October, 1654. A beggar named Alexander Agnew was refused a handout by Campbell.[11] Agnew had promised to cause the family harm and over the next two years strange phenomena were alleged to have occurred at the house. This included the mysterious cutting of warp thread, demonic voices, strange whistling noises and stones being thrown.[12] The poltergeist claims have been dismissed by researchers as a hoax. Magic historian Thomas Frost suggested that the phenomena was the result of conjuring trickery.[13] The story was given to Sinclair by Campbell's son Thomas, a philosophy student from a college in Glasgow who was living at the household. Folklorist Andrew Lang suggested that Thomas had produced the phenomena fraudulently.[14]

Historian David Damrosch has noted that Alexander Agnew commonly called the "Jock of Broad Scotland" was the first person in Scottish history to publicly deny the existence of God.[15] He was hanged at Dumfries for blasphemy on 21 May 1656.[16]

Geological pioneer

[edit]A long-neglected aspect deriving from Sinclair's work as a mineral surveyor is that the last part of Hydrostaticks - a short History of Coal - includes the first published geological cross section in which he treats the strata in purely geometric terms.[17]

Controversy

[edit]James Gregory, then a professor at the University of St Andrews, attacked Sinclair in a 1672 pamphlet The New and Great Art of Weighing Vanity, under the name of Patrick Mather or Mathers, archbeadle of the University of St Andrews. Gregory was both a Cartesian and an Episcopalian, and self-consciously invoked the Hobbes-Wallis controversy in aiming at the non-conformist Sinclair.[5] The title of Gregory's pamphlet ridiculed Sinclair's 1669 book Ars Nova et Magna Gravitatis et Levitatis (The New and Great Art of Heaviness and Lightness). An appendix to the work, Tentamina de motu penduli et projectorum,[18] was a more important essay on dynamics, regarded by D. T. Whiteside as a probable source of Isaac Newton’s theory of resisted motion.[19] Sinclair wrote an answer to Gregory,[20] but it remained unpublished.

In 1684 he published as his own a work Truth's Victory over Error. It was in fact an English translation by Sinclair of the Latin inaugural dissertation given by David Dickson, who became Professor of Divinity, Glasgow in 1640, on the occasion in 1650 when he moved to Edinburgh. This was pointed out in short order.[21]

Publications

[edit]- Tyrocinia Mathematica (1661)

- Ars Nova et Magna Gravitatis et Levitatis (1669)

- The Hydrostaticks; or, the weight, force, and pressure of fluid bodies: made evident by physical and sensible experiments. Together with some miscellany observations, the last whereof is a short history of coal, and of all the common, and proper, accidents thereof; a subject never treated of before (1672)

- Hydrostatical Experiments (1680)

- Satan's Invisible World Discovered (1685, republished 1814)

- Satan's Invisible World Discovered at Project Gutenberg

- Principles of Astronomy and Navigation (1688)

References

[edit]- ^ Craik, A.D.D., 2018, Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 72(3), he hydrostatical works of George Sinclair (c.1630–1696): their neglect and criticism

- ^ a b Craik, A.D.D. & Spittle, D., 2018, Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 73(1), The hydrostatical works of George Sinclair (c. 1630–1696): an addendum

- ^ Sinclair, George (1871). Satan's Invisible World Discovered. Edinburgh: T.G. Stevenson.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b Clare Jackson, Restoration Scotland, 1660-1690: royalist politics, religion and ideas (2003), p. 187.

- ^ "George Sinclair". www.electricscotland.com. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ John, Anderson; McConnell, Anita (2004). "Sinclair, George (d. 1696?), natural philosopher". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25615. Retrieved 26 January 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Mathematics in Glasgow University in 1883". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Povey, Thomas. (2015). Professor Povey's Perplexing Problems: Pre-University Physics and Maths. Oneworld Publications. pp. 209-210. ISBN 978-1-78074-775-0

- ^ Henderson, Lizanne. (2009). Fantastical Imaginations: The Supernatural in Scottish History and Culture. John Donald. p. 95

- ^ Lamont-Brown, Raymond. (1994). Scottish Witchcraft. Chambers. pp. 29-30

- ^ Seth, Ronald. (1969). In the Name of the Devil: Great Scottish Witchcraft Cases. Jarrolds. pp. 77-78

- ^ Frost, Thomas. (1876). The Lives of the Conjurors. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 108-110.

- ^ Lang, Andrew. (1893). Fairies and Psychical Research. In Robert Kirk. The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies. London: David Nutt. pp. 55-56. "In this affair a boy called Thomas, a son of the unlucky householder, was clearly the agent. The phenomena were stone-throwing, beating with sticks, levitation of a plate, and a great deal of voices, probably uttered by the aforesaid Thomas."

- ^ Damrosch, David. (1999). The Longman Anthology of British Literature. Longman. pp. 754-755

- ^ Levy, Leonard Williams. (1993). Blasphemy: Verbal Offense Against the Sacred, From Moses to Salman Rushdie. University of California Press. p. 167.

- ^ Mike Leeder,(2020), Measures for Measure, pp.16-26: Chapter 2, Beginning of Coallery: George Sinclair, 'Scoto-Lothiani'

- ^ "Archimedes Project". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ Whiteside, D. T. (1970). "1970JHA.....1....5W Page 14". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 1: 5. Bibcode:1970JHA.....1....5W. doi:10.1177/002182867000100103. S2CID 125845242. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Cacus pulled out of his den by the heels, or the pamphlet entitled, the New and Great Art of Weighing Vanity examined, and found to be a New and Great Act of Vanity.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.