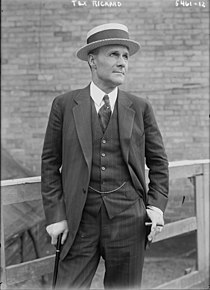

Tex Rickard

Tex Rickard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George Lewis Rickard January 2, 1870[1] Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | January 6, 1929 (aged 59)[1] Miami, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1896–1929 |

| Known for |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

George Lewis "Tex" Rickard (January 2, 1870 – January 6, 1929[1]) was an American boxing promoter, founder of the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League (NHL), and builder of the third incarnation of Madison Square Garden in New York City. During the 1920s, Tex Rickard was the leading promoter of the day, and he has been compared to P. T. Barnum and Don King.[citation needed] Sports journalist Frank Deford has written that Rickard "first recognized the potential of the star system."[2] Rickard also operated several saloons, hotels, and casinos, all named Northern and located in Alaska, Nevada, and Canada.

Early years

[edit]Rickard was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His youth was spent in Sherman, Texas, where his parents had moved when he was four years old. His father died, and his mother then moved to Henrietta, Texas, while he was still a young boy.[1] Rickard became a cowboy at age 11, after the death of his father.[3][4] At age 23, he was elected marshal of Henrietta, Texas.[5] He acquired the nickname "Tex" at this time.[1][5]

On July 2, 1894, Rickard married Leona Bittick, whose father was a physician in Henrietta. On February 3, 1895, their son, Curtis L. Rickard, was born. However, Leona Rickard died on March 11, 1895, and Curtis Rickard died on May 4, 1895.[6]

Alaska

[edit]In November 1895, Rickard went to Alaska, drawn by the discovery of gold there.[5] Thus he was in the region when he learned of the nearby Klondike Gold Rush of 1897. Along with most of the other residents of Circle City, Alaska, he hurried to the Klondike, where he and his partner, Harry Ash, staked claims.[5] They eventually sold their holdings for nearly $60,000.[5] They then opened the Northern,[5] a saloon, hotel, and gambling hall in Dawson City, Yukon, Canada.[7][8] Rickard lost everything—including his share of the Northern—through gambling.[5] While working as a poker dealer and bartender at the Monte Carlo saloon and gambling hall, he and Wilson Mizner began promoting boxing matches.[5] In spring 1899, with only $35,[4] Rickard (and many others) left to chase the gold strikes in Nome, Alaska.[5]

Rickard was a friend of Wyatt Earp who was also a boxing fan and had officiated a number of matches during his life, including the infamous match between Bob Fitzsimmons and Tom Sharkey in San Francisco on December 2, 1896. Rickard sent Earp a number of letters belittling Wyatt's steady but small income managing a store in St. Michael as "chickenfeed" and persuaded him to relocate to Nome.[9] The two were lifelong friends, although for a brief period of time, they operated competing saloons in Nome. Earp and a partner owned the Dexter Saloon, and Rickard owned the Northern hotel and bar.[10][11][12]

In 1902, Rickard married Edith Mae Haig of Sacramento, California. They had a daughter, Bessie, who died in 1907. Edith Rickard died on October 30, 1925, at her home in New York City.[13]

Nevada

[edit]By 1906, Rickard was running the Northern saloon and casino in Goldfield, Nevada.[4][14] In Goldfield, he promoted a professional boxing match between Joe Gans and Battling Nelson. The gate receipt of $69,715 set a record.[6] A year later, Rickard opened the Northern Hotel in Ely, Nevada.[15] Rickard also organized the Ely Athletic club and was the owner of several mining properties in the Ely area.[16]

In December 1909, Rickard and John Gleason won the right to stage the world heavyweight championship fight between James J. Jeffries and Jack Johnson.[17] Rickard planned to hold the fight on July 4, 1910, in San Francisco, however opposition from Governor James Gillett and Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb caused Rickard to move it to Reno, Nevada.[18] Rickard and Gleason made a profit of about $120,000 on the fight, which was won by Johnson.[19]

South America

[edit]On February 18, 1911, Rickard announced that he was "through with the business of prize fighting" and set sail for Argentina.[20] There, he acquired between 270,000 and 327,000 acres in Paraguay to start a cattle ranch.[6] Rickard managed the ranch for the Farquhar syndicate, whose land holdings in South America total over 5 million acres. At its peak, the ranch consisted of about 1 million acres and had between 20,000 and 50,000 head of cattle.[6][21] In 1913, Rickard's ranch was involved in a political controversy between Paraguay, Argentina, Bolivia, and Brazil. Two of his employees were killed by Bolivian soldiers stationed in the disputed territory. That same year, Rickard accompanied Theodore Roosevelt on part of the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition. The cattle business failed by the end of 1915. Rickard's loss was stated to be about $1 million.[6]

Hockey

[edit]According to NHL.com, in 1924, Tex Rickard was the first man to refer to the Montreal Canadiens as "the Habs." Rickard apparently told a reporter that the "H" on the Canadiens' sweaters was for "Habitants".[22] At the time, this was a pejorative term equivalent to redneck in Canadian French.

Return to boxing

[edit]

In 1916, Rickard returned to the United States.[6] On February 3, Jess Willard agreed to Rickard's offer to fight Frank Moran in New York City.[23] The fight was held on March 17, 1916, at Madison Square Garden, then in its second incarnation, at 26th Street and Madison Avenue in Manhattan. The $152,000 in gate receipts set a new record for an indoor event and the purse was the largest ever awarded for a no decision.[6]

Rickard promoted the July 4, 1919, fight between world heavyweight champion Jess Willard and Jack Dempsey in Toledo, Ohio.[24] The fight only drew 20,000 to 21,000 spectators (the area seated 80,000) and the total receipts were estimated to be $452,000.[25] After expenses, Rickard made a profit of $100,000.[6]

After the Willard–Dempsey fight, Rickard began bidding for a title match between Dempsey and Georges Carpentier.[26] The Jack Dempsey vs. Georges Carpentier fight took place on July 2, 1921, in a specially built arena in Jersey City, New Jersey. The bout, which drew a record crowd of 90,000, was the first-ever boxing fight to produce a million dollar gate (at a then record of $1,789,238) as well as the first world title fight to be carried over on radio.[27][28] Rickard's profit on the fight was reported to be $550,000.[29]

On July 12, 1920, shortly after the Walker Law reestablished legal boxing in the state of New York, Rickard secured a ten-year lease of Madison Square Garden from its owner, the New York Life Insurance Company.[30] He promoted a number of championship as well as amateur boxing bouts at the Garden. His largest gate at the Garden came from the Jack Dempsey–Bill Brennan fight on December 14, 1920. The Benny Leonard–Ritchie Mitchell and Johnny Wilson–Mike O'Dowd fights also drew well.[31] In addition to boxing, Rickard hosted a number of other events, including six-day bicycle races, and constructed the world's largest indoor swimming pool at the Garden.[31]

On February 17, 1922, Rickard was indicted on charges of abducting and sexually assaulting four underage girls. He lost his license to make and promote boxing matches in New York State and gave up control of the Garden.[31][32] Rickard was found not guilty on one of the indictments on March 29, 1922, and the others were dropped as a result.[33] After the trial, Rickard's attorney, Max Steuer, accused two workers of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children of demanding $50,000 from Rickard in exchange for the girls changing their testimony at trial; however, the district attorney could not find any evidence to corroborate this claim.[34][35]

On May 12, 1923, Rickard promoted the first boxing card at Yankee Stadium. It drew 60,000 spectators (a then-record crowd for a boxing bout in New York state) and made $182,903.26, which was donated to Millicent Hearst's Milk Fund.[6][36]

On September 14, 1923, Rickard promoted his second million dollar gate when around 100,000 people attended the Jack Dempsey vs. Luis Ángel Firpo fight at the Polo Grounds.[6]

In September 1924, Rickard promoted the fight between Luis Ángel Firpo and Harry Willis in Jersey City. The fight was attended by 60,000, but the paid attendance was only 48,500.[37] Rickard lost $5,005 on the bout.[38]

On March 19, 1925, Rickard was convicted of violating a federal law that prevented the interstate transportation of fight films. He faced jail time, but was instead fined $7,000.[39]

In 1926, Rickard promoted the Jack Dempsey–Gene Tunney fight at Sesquicentennial Stadium in Philadelphia. The bout attracted a world record crowd of 135,000 and brought in a record gate of $1.895 million. He also promoted the rematch, now known as The Long Count Fight, which was held on September 22, 1927, at Soldier Field in Chicago. This fight brought in the first $2 million gate ($2.658 million) and was the first to feature a $1 million purse.[6] Rickard reported that between 1924 and 1926 his gate receipts totaled $7.79 million, of which he kept 80% after taxes.[40]

Madison Square Garden

[edit]On May 31, 1923, Rickard filed incorporation papers for the New Madison Square Garden Corporation, a company formed for the purpose of building and operating a new sports arena in New York City.[41] In 1924 he purchased a car barn block on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets.[42] He acquired the rights to the name Madison Square Garden, as the building's owners planned on tearing it down and replacing it with an office building. Thomas W. Lamb was selected to design the new building. Destruction of the car barns began on January 9, 1925.[43] The new arena opened on November 28, 1925. The first event was the preliminaries for the Six Days of New York.[44] It hosted its first major event on December 11, 1925, when a record indoor crowd of 20,000 attended the Paul Berlenbach-Jack Delaney fight.[45] The $148,155 gate broke the record for an indoor boxing event.[6]

In January 1926, Rickard purchased WWGL radio, which he moved to the Garden and renamed WMSG.[46]

Following the success of the New York Americans in the Garden's first year, the Madison Square Garden Corporation decided to establish a second team, this one controlled by the corporation itself. The new team was nicknamed "Tex's Rangers" and later became known as the New York Rangers.[47]

Other ventures

[edit]Rickard sought to repeat the success of the Madison Square Garden by building seven "Madison Square Gardens" around the country.[48] In 1927, a group led by Rickard signed a 25-year lease for a sports arena at the new North Station facility in Boston.[49] The Boston Garden opened on November 17, 1928.[50]

In 1929, Rickard and George R. K. Carter opened the Miami Beach Kennel Club greyhound track. They also planned a number of other ventures, including a jai-alai grounds adjacent to the kennel club and a horse track on an island in Biscayne Bay.[51] Rickard also hoped to someday to build a hotel and casino that would rival those in Monte Carlo.[6]

Personal life

[edit]Rickard met Maxine Hodges, a former actress 33 years his junior at the Dempsey–Firpo fight. The couple married on October 7, 1926, in Lewisburg, West Virginia. On June 7, 1927, the couple's daughter, Maxine Texas Rickard, was born.[6]

On December 26, 1928, Rickard left New York for Miami Beach, Florida, where he was completing arrangements for a fight between Jack Sharkey and Young Stribling and attending the opening of the Miami Beach Kennel Club. On New Year's Eve, Rickard was stricken with appendicitis and was operated on.[52] Rickard died on January 6, 1929, due to complications from his appendectomy.[1] He was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Rickard, George Lewis (1871–1929)". tshaonline.org. The Handbook of Texas Online.

- ^ Deford, Frank (1971), Five Strides On The Banked Track, Little, Brown and Company, p. 110

- ^ Bunk, Brian (April 13, 2015). "Tex Rickard and the Making of Modern Sports". We're History. Retrieved January 3, 2017 – via werehistory.org.

- ^ a b c Treanor, Vincent (February 14, 1911). "Tex Rickard Tells How He Won and Lost Big Fortunes During Checkered Career". The Pittsburg Press. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "From the Klondike muck to Madison Square Gardens". hougengroup.com. The Hougen Group of Companies. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Aycock, Colleen & Scott, Mark (2012). Tex Rickard: Boxing's Greatest Promoter. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-6591-0.

- ^ Gates, Michael (December 9, 2016). "Tex Rickard: From Dawson City to Madison Square Garden". Yukon News. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ "George (Tex) Rickard". ibhof.com. International Boxing Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ "Wyatt Earp's Alaskan Adventure". True West Magazine. March 18, 2014. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017.

- ^ "Wyatt Earp's Dexter Saloon" (PDF). sewardpeninsula.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Barra, Alan (November 26, 1995). "When Referee Wyatt Earp Laid Down the Law". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Nome, Alaska, 1902". Life. October 15, 1965. Retrieved December 31, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Wife of 'Tex' Rickard Dead". The New York Times. October 30, 1925.

- ^ O'Read, Effie (July 7, 1957). "Long Before It Was Finished, Ely Hotel Held a Grand Ball". Nevada State Journal. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Myrick, David F. (1992). Railroads of Nevada and Eastern California – Volume I: The Northern Roads. University of Nevada Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780874171938.

- ^ ""Rickard's Luck" Shows in Mining". The White Pine News. December 25, 1906. p. 35. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ ""Tex" Rickard's Bid For Fight Accepted". The New York Times. December 3, 1909.

- ^ "Reno to Get Fight; Suit Begins To-Day". The New York Times. June 17, 1910.

- ^ "Jeffries Offended Followers at Reno". The New York Times. July 6, 1910.

- ^ "'Tex' Rickard Departs for South America". San Francisco Call. February 19, 1911 – via ucr.edu.

- ^ "Paraguay a Fertile Pasture". The Boston Daily Globe. June 6, 1915.

- ^ "Why are the Montreal Canadiens called the Habs?". About.com. 2008. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ "Willard and Moran to Box Here Mar. 17". The New York Times. February 4, 1916.

- ^ "Toledo Chosen as Scene of Willard-Dempsey Heavyweight Championship Bout". The New York Times. May 6, 1919.

- ^ "Less Than $500,000 Rickard Now Says". The New York Times. July 9, 1919.

- ^ "Rickard Bidding For Title Match". The New York Times. December 18, 1919.

- ^ "Sport: Prizefighting's Million-Dollar Gates". Time. March 8, 1971. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Wade Forrester (July 2, 2013). "On This Day In Sports". Onthisdayinsports.blogspot.mx. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Rickard's Profit of Fight $550,000". The Boston Daily Globe. July 4, 1921.

- ^ "'Tex' Rickard Gets Madison Sq. Garden". The New York Times. July 13, 1920.

- ^ a b c "Rickard Gives Up Control of the Garden". The New York Times. February 18, 1922.

- ^ "Indict Tex Rickard on Girls' Charges". The New York Times. February 17, 1922.

- ^ "Rickard Not Guilty; Verdict At 12:19 AM; Jury Out 91 Minutes". The New York Times. March 29, 1922.

- ^ "$50,000 Bribe Plot Charged by Rickard". The New York Times. April 1, 1922.

- ^ "Rickard Summoned to Bribe Inquiry". The New York Times. April 4, 1922.

- ^ "Vast Crowd Shows Good Humor". The New York Times. May 13, 1923.

- ^ "Rickard Displeased With the Big Bout". The New York Times. September 13, 1924.

- ^ "Rickard Lost $5,005 on Wills-Firpo Bout". The New York Times. October 1, 1924.

- ^ "Tex Rickard Fined $7,000". The Boston Daily Globe. March 30, 1925.

- ^ "Business: Business Notes, Jan. 10, 1927". Time. January 10, 1927. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Rickard Files Papers". The New York Times. June 1, 1923.

- ^ "Plan 2 Big Arenas for Sport Uptown". The New York Times. August 7, 1924.

- ^ "New Rickard Arena Work is Under Way". The New York Times. January 10, 1925.

- ^ "Madison Sq. Garden Opens in New Home". The New York Times. November 29, 1925.

- ^ "Berlenbach Wins; Defeats Delaney". The New York Times. November 29, 1925.

- ^ "Rickard to Radio Events at Garden". The New York Times. January 16, 1926.

- ^ Fischler, Stan & Weinstock, Zachary (2016). Rangers vs. Islanders: Denis Potvin, Mark Messier, and Everything Else You Wanted to Know about New York's Greatest Hockey Rivalry. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6132-1932-4.

- ^ "The Last Days of a Garden Where Memories Grew". The New York Times. April 16, 1995. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ "Coliseum Will Top New Boston Station". The Boston Daily Globe. November 16, 1927.

- ^ "Routis is Defeated by Honeyboy Finnegan". The New York Times. November 18, 1928.

- ^ "Miami Beach Mourns Passing of Rickard". The New York Times. January 8, 1929.

- ^ "Rickard Stricken by Acute Appendicitis; Operated On in Miami Beach Hospital". The New York Times. January 2, 1929.