Geology of Eswatini

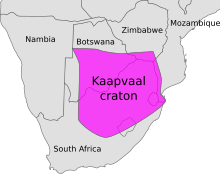

The geology of Eswatini formed beginning 3.6 billion years ago, in the Archean Eon of the Precambrian. Eswatini is the only country entirely underlain by the Kaapvaal Craton, one of the oldest pieces of stable continental crust and the only craton regarded as "pristine" by geologists, other than the Yilgarn Craton in Australia.[citation needed] As such, the country has very ancient granite, gneiss and in some cases sedimentary rocks from the Archean into the Proterozoic, overlain by sedimentary rocks and igneous rocks formed during the last 539 million years of the Phanerozoic as part of the Karoo Supergroup. Intensive weathering has created thick zones of saprolite and heavily weathered soils.

Stratigraphy and geologic history

[edit]

Eswatini is built on 3.6 to 2.5 billion year old Archean continental crust that forms the Kaapvaal Craton spanning into South Africa, northern Lesotho, western Mozambique, Botswana and southern Zimbabwe. The Precambrian rocks of Eswatini from this period are primarily gneiss and granite, formed between 3.4 and 2.6 billion years ago, based on rubidium-strontium dating analysis in 1976.

The two rock units of the basement in Eswatini are the Ancient Gneiss Complex and 20 kilometer thick mafic and ultramafic volcanic rocks of the Paleoarchean Swaziland Supergroup[needs update?] includes tonalite gneiss, ironstone, conglomerate and other sediments. The Swaziland Supergroup and the Ancient Gneiss Complex are overlain by tuff, shale, quartzite, conglomerate and graywacke. The two formations are separated by faulting.[1]

Granite, gneiss, amphibolite and a variety of sediments and volcanics formed the Pongolo Supergroup in the Mesoarchean. The Neoarchean and Paleoproterozoic are represented by granite and granodiorite.

In the Paleozoic, a major rift valley opened across the supercontinent Gondwana, spanning what is now southern Africa and southern South America. The basin filled with sediments, producing the Karoo Supergroup, the most extensive stratigraphic unit in southern Africa. The Karoo Supergroup in Eswatini is composed of Permian claystones as well as basalt and rhyolite from the Early Jurassic.[2]

Soils and saprolite

[edit]The Swaziland Middleveld[needs update?] is dominated by soils and saprolite, formed out of diorite and granodiorite. Saprolite formed due to intense chemical weathering in the Early Cretaceous, with an upper oxidation zone and a lower reduction zone. In lower saprolite zones, plagioclase weathered to kaolin. Mica, feldspar and amphibole are most weathered nearest the surface and iron oxides are more common close to the surface as well. Smectite clay represents transitional zones of weathering.

Most soils in the Middleveld are oxisols, cambisols or acrisols, with significant quartz and kaolinite, as well as some illite and gibbsite.[3]

Hydrogeology

[edit]Most of central and western Eswatini is underlain by low to moderate productivity aquifers in Precambrian basement rock. A narrow north-south band in the center of the country hosts fracture-flow sedimentary aquifers, while a different north-south band in the east is moderate yield volcanic rocks.[4]

Natural resource geology

[edit]Eswatini has diverse mineral resources, including diamonds, gold, kaolin, silica sand, arsenic, manganese, copper, nickel and tin. However, most of these deposits are small and are not mined. The Maloma Mine in eastern Eswatini is one of the few active mines in the country, extracting coal.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Davies, R. D.; Allsopp, H. L. (1976). "Strontium isotopic evidence relating to the evolution of the lower Precambrian granitic crust in Swaziland". Geology. 4 (9): 553–556. Bibcode:1976Geo.....4..553D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1976)4<553:SIERTT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Schluter, Thomas (2006). Geological Atlas of Africa. Springer. p. 243.

- ^ Scholten, T.; Felix-Henningsen, P.; Schotte, M. (1997). "Geology, soils and saprolites of the Swaziland Middleveld". Soil Technology. 11 (3): 229–246. doi:10.1016/S0933-3630(97)00010-X.

- ^ "Hydrogeology of Swaziland". British Geological Survey.

- ^ "2010 Minerals Yearbook: Lesotho and Swaziland" (PDF). US Geological Survey.