Anton Denikin

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Anton Denikin | |

|---|---|

Антон Деникин | |

Portrait, c. 1918–1919 | |

| Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of South Russia | |

| In office 8 January 1919 – 4 April 1920 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Pyotr Wrangel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 December 1872 Vlotslavek, Warsaw Governorate, Vistula Land, Imperial Russia (now Włocławek, Kuyavian–Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland) |

| Died | 7 August 1947 (aged 74) Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States |

| Spouse | Xenia Chizh |

| Relations | Marina Denikina (daughter) |

| Awards | See below |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1890–1917) (1917–1920) |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1890–1920 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (Russian: Антон Иванович Деникин, IPA: [ɐnˈton ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ dʲɪˈnʲikʲɪn]; 16 December [O.S. 4 December] 1872 – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces of South Russia during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1923. Previously, he was a general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I.

His forces' implementation of the White Terror was known for pogroms.[1]

Childhood

[edit]Denikin was born on 16 December 1872, in the village of Szpetal Dolny, part of the city Włocławek in Warsaw Governorate of the Russian Empire (now Poland). His father, Ivan Efimovich Denikin, had been born a serf in the province of Saratov. Sent as a recruit to do 25 years of military service, the elder Denikin became an officer in the 22nd year of his army service in 1856. He retired from the army in 1869 with the rank of major.

In 1869, Ivan Denikin married Polish seamstress Elżbieta Wrzesińska as his second wife. Anton Denikin, the couple's only child, spoke both Russian and Polish growing up. His father's Russian patriotism and devotion to the Russian Orthodox religion led Anton Denikin to the Russian army.

The Denikins lived very close to poverty, with the retired major's small pension as their only source of income, and their finances worsened after Ivan's death in 1885. Anton Denikin at this time began tutoring younger schoolmates to support the family. In 1890, Denikin enrolled at the Kiev Junker School, a military college from which he graduated in 1892. The twenty-year-old Denikin joined an artillery brigade, in which he served for three years.

In 1895, he was first accepted into the General Staff Academy, where he did not meet the academic requirements in the first of his two years. After this disappointment, Denikin attempted to attain acceptance again. On his next attempt he did better and finished fourteenth in his class. However, to his misfortune, the academy decided to introduce a new system of calculating grades and as a result Denikin was not offered a staff appointment after the final exams. He protested the decision to the highest authority (the Grand Duke).[which?]

After being offered a settlement according to which he would rescind his complaint in order to attain acceptance into the General Staff school again, Denikin declined, insulted.

Denikin first saw active service during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. In 1905, he won promotion to the rank of colonel. In 1910, he became commander of the 17th infantry regiment. A few weeks before the outbreak of the First World War, Denikin reached the rank of major-general.

World War I

[edit]By the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 Denikin was chief of staff of the Kiev Military District. He was initially appointed quartermaster of General Brusilov's 8th Army. Not one for staff service, Denikin petitioned for an appointment to a fighting front. He was transferred to the 4th Rifle Brigade, which was transformed into the 4th Rifle Division in 1915. This was one of the formations cited by Brusilov in his Order No. 643 of 5 (18) April 1916, which sought to end fraternization between Russian and Austrian troops.[2]

In October 1916, he was appointed to command the Russian 8th Army Corps and lead troops in Romania. Following the February Revolution and the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II, he became Chief of Staff to Mikhail Alekseev, then Aleksei Brusilov, and finally Lavr Kornilov. Denikin was concurrently commander of the Southwestern Front from 20 July (2 August) to 16 (29) August 1917. He supported the attempted coup of his superior, Kornilov, in September 1917 and was arrested and imprisoned with him. After this Alekseev would be reappointed commander-in-Chief.[3]

Civil War

[edit]

Following the October Revolution both Denikin and Kornilov escaped to Novocherkassk in the Northern Caucasus and, with other Tsarist officers, formed the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army, initially commanded by Alekseev. Kornilov was killed in April 1918 near Ekaterinodar and the Volunteer Army came under Denikin's command thanks in part to the support of fellow general Sergey Markov. Kornilov's disastrous attempt to take the city was finally cancelled and the army retreated towards the north-east, evading destruction and ending the campaign which would become known as the Ice March. There was some sentiment to place Grand Duke Nicholas in overall command but Denikin was not interested in sharing power. In June–November 1918, Denikin launched the highly successful Second Kuban Campaign which gave him control of the entire area between the Black and Caspian Sea.[4]

In the summer of 1919, Denikin led the assault of the southern White forces in their final push to capture Moscow. For a time, it appeared that the White Army would succeed in its drive; Leon Trotsky, as the supreme commander of the Red Army, hastily concluded an agreement with Nestor Makhno's anarchist Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine for mutual support. Makhno duly turned his Insurgent Army east and led it against Denikin's extended lines of supply, forcing the Whites to retreat. Denikin's army would be decisively defeated at Orel in October 1919, some 360 km south of Moscow.[citation needed] The White forces in southern Russia would be in constant retreat thereafter, eventually reaching the Crimea in March 1920.

On 4 January 1920, with defeat and capture by the Bolsheviks in Siberia imminent, Admiral Alexander Kolchak named Denikin as his successor as Supreme Ruler (Verkhovnyy Pravitel), but Denikin accepted neither the functions nor the style of Supreme Leader.[5]

Meanwhile, the Soviet government immediately tore up its agreement with Makhno and attacked his anarchist forces. After a seesaw series of battles in which both sides gained ground, Trotsky's more numerous and better equipped Red Army troops decisively defeated and dispersed Makhno's Insurgent Army.

Although Denikin refused to recognise the independence of Azerbaijan and Georgia, in maintaining friendly relations with Armenia he recognised their independence[6] and supplied them with ammunition during the Muslim uprisings in Kars and Sharur–Nakhichevan.[7]

Antisemitism and anti-Masonry

[edit]

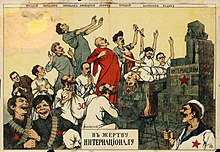

During the Russian Civil War, an estimated 150,000 Jews were killed in pogroms. Ukrainian forces, nominally under the control of Symon Petliura, perpetrated approximately 40 percent of the recorded pogroms, although Petliura never ordered his forces to engage in such activity and eventually exhorted his troops to refrain from the violence.[8] The White Army is associated with 17 percent of the attacks, and was generally responsible for the most active propaganda campaign against Jews, whom they openly associated with communism.[9][10] The Red Army is blamed for 9 percent of the pogroms.

In the territories it occupied, Denikin's army carried out mass executions and plunder, in what was later known as the White Terror. In the town of Maykop in Circassia during September 1918, more than 4,000 people were massacred by General Pokrovsky's forces.[11] In the small town of Fastov alone, Denikin's Volunteer Army murdered over 1,500 Jews, mostly elderly, women, and children.[citation needed]

The press of the Denikin regime regularly incited violence against communist Jews and Jews seen as communists in the context of treason committed by Red agents. For example, a proclamation by one of Denikin's generals incited people to "arm themselves" in order to extirpate "the evil force which lives in the hearts of Jew-communists."[12]

Religious and faithful to the Russian Orthodox Church, Denikin did not criticise the pogroms against the Jewish population until the end of 1919. Denikin believed that most people had reasons to hate Jews and wished to avoid an issue that divided his officers. Many of them, intensely anti-Semitic, allowed pogroms under their watch, which turned into a method of terror against the Jewish population and served to earn the favour of the Ukrainian people for much of 1919.[citation needed]

Western sponsors were dismayed at the widespread antisemitism in the Whites' officer ranks, especially as the Bolsheviks sought to officially prohibit acts of anti-Semitism. Winston Churchill personally warned General Denikin that:

[M]y task in winning support in Parliament for the Russian Nationalist cause will be infinitely harder if well-authenticated complaints continue to be received from Jews in the zone of the Volunteer Armies.[13]

John Ernest Hodgson, a British war correspondent with Denikin's forces, said the following of Denikin's and his officers' antisemitism:

I had not been with Denikin more than a month before I was forced to the conclusion that the Jew represented a very big element in the Russian upheaval. The officers and men of the Army laid practically all the blame for their country's troubles on the Hebrew. They held that the whole cataclysm had been engineered by some great and mysterious secret society of international Jews, who, in the pay and at the orders of Germany, had seized the psychological moment and snatched the reins of government. All the figures and facts that were then available appeared to lend colour to this contention. No less than 82 per cent of the Bolshevik Commissars were known to be Jews, the fierce and implacable 'Trotsky,' who shared office with Lenin, being a Yiddisher whose real name was Bronstein. Among Denikin's officers this idea was an obsession of such terrible bitterness and insistency as to lead them into making statements of the wildest and most fantastic character. Many of them had persuaded themselves that Freemasonry was, in alliance with the Jews, part and parcel of the Bolshevik machine, and that what they had called the diabolical schemes for Russia's downfall had been hatched in the Petrograd and Moscow Masonic lodges. When I told them that I and most of my best friends were Freemasons, and that England owed a great deal to its loyal Jews, they stared at me askance and sadly shook their heads in fear for England's credulity in trusting the chosen race. One even asked me quietly whether I personally was a Jew. When America showed herself decidedly against any kind of interference in Russia, the idea soon gained wide credence that President Woodrow Wilson was a Jew, while Mr. Lloyd George was referred to as a Jew whenever a cable from England appeared to show him as being lukewarm in support of the anti-Bolsheviks.[14]

Exile

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Facing increasingly sharp criticism and emotionally exhausted, Denikin resigned in April 1920 in favor of General Baron Pyotr Wrangel, who later established the Russian All-Military Union. Denikin left the Crimea by ship to Istanbul and then to London. He spent a few months in England, then moved to Belgium, and later to Hungary.

From 1926, Denikin lived in France. Although he remained bitterly opposed to Russia's Communist government, he chose to exist discreetly on the periphery of politics, spending most of his time writing and lecturing. This did not prevent the Soviets from unsuccessfully targeting him for abduction in the same effort that snared exiled General Alexander Kutepov in 1930 and General Yevgeny Miller in 1937 (both members of the Russian All-Military Union). White Against Red – The Life of General Anton Denikin gives possibly the definitive account of the intrigues during these early Soviet "wet-ops".

Denikin was a writer, and prior to World War I had written several pieces in which he criticised the shortcomings of his beloved Russian Army. His voluminous writings after the Russian Civil War (written while living in exile) are notable for their analytical tone and candour. Since he enjoyed writing and most of his income was derived from it, Denikin began to consider himself a full-time writer and developed close friendships with several Russian émigré authors—among them Ivan Bunin (a Nobel laureate), Ivan Shmelev, and Aleksandr Kuprin.

Although respected by some of the community of Russian exiles, Denikin was disliked by émigrés of both political extremes, right and left. With the fall of France in 1940, Denikin left Paris in order to avoid imprisonment by the Germans. Although he was eventually captured, he declined all attempts to co-opt him for use in Nazi anti-Soviet propaganda. The Germans did not press the matter and Denikin was allowed to remain in rural exile. Denikin denounced White Russian collaborators in 1939.[15]

"White or Red, our fatherland remains our fatherland. Whoever may aid Russia's enemies cannot call himself a patriot, no matter what ideological excuse he may use for taking money to fight his own people."

At the conclusion of World War II, correctly anticipating their likely fate at the hands of Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union, Denikin attempted to persuade the Western Allies not to forcibly repatriate Soviet POWs (see also Operation Keelhaul). He was largely unsuccessful in his effort.

From 1945 until his death in 1947, Denikin lived in the United States, in New York City. On 7 August 1947, at the age of 74, he died of a heart attack while on vacation near Ann Arbor, Michigan. Denikin was buried with military honours in Detroit. His remains were later transferred to St. Vladimir's Cemetery in Jackson, New Jersey. His wife, Xenia Vasilievna Chizh (1892–1973), was buried at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois cemetery near Paris.

On 3 October 2005, in accordance with the wishes of his daughter Marina Denikina and by authority of the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, General Denikin's remains were transferred from the United States and buried together with Ivan Ilyin's at the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow.[16]

The importance of Denikin's diary for explaining the relationship between "Great and little Russia, Ukraine" was cited by Putin during his 24 May 2009 visit to the Donskoy Monastery. "He says nobody should be allowed to interfere between us. This is only Russia's right."[17] Putin emphasized that Denikin's diary was worth reading, especially the passages in which he described Ukraine as an indivisible part of Russia.[18]

Honours

[edit]Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd degree with Swords (1904); 3rd degree (1902)

Order of St. Anne, 2nd degree with Swords (1905); 3rd degree with swords and bows (1904)

Order of St. Anne, 2nd degree with Swords (1905); 3rd degree with swords and bows (1904) Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree (18 April 1914); 4th degree (6 December 1909)

Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree (18 April 1914); 4th degree (6 December 1909) Order of St. George, 3rd degree (3 November 1915); 4th degree (24 April 1915)

Order of St. George, 3rd degree (3 November 1915); 4th degree (24 April 1915)- Golden Sword of St. George (10 November 1915)

- Golden Sword of St. George, decorated with diamonds, with the inscription "For the double release of Lutsk (22 September 1916)

Order of Michael the Brave, 3rd degree, 1917 (Romania)

Order of Michael the Brave, 3rd degree, 1917 (Romania) Croix de Guerre, 1914-1918, 1917 (France)

Croix de Guerre, 1914-1918, 1917 (France) Sign of the 1st Kuban Ice Campaign, 1918

Sign of the 1st Kuban Ice Campaign, 1918 Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, 1919 (UK)

Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, 1919 (UK) Order of the White Eagle (Serbia)[19]

Order of the White Eagle (Serbia)[19]

Denikin's works

[edit]Denikin wrote several books, including:

- Russian Turmoil. Memoirs: Military, Social & Political. Hutchinson. London. 1922. (only volume 1 of 5 has been published in English.)

- Republished: Hyperion Press. 1973. ISBN 978-0-88355-100-4

- The White Army. Translated by Catherine Zvegintsov. Jonathan Cape, 1930.

- Republished: Hyperion Press. 1973. ISBN 978-0-88355-101-1.

- Republished: Ian Faulkner Publishing. Cambridge. 1992. ISBN 978-1-85763-010-7.

- The Career of a Tsarist Officer: Memoirs, 1872-1916. Translated by Margaret Patoski. University of Minnesota Press. 1975.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hochschild, Adam (7 October 2022). "Why Putin Made Peace With the Soviets' Archenemies". The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Jukes, Geoffrey. Carpathian Disaster: Death of an Army, pp. 117-120. New York: Ballantine Books, 1971.

- ^ Jukes, pp. 155-157.

- ^ Yegorov, O. (27 December 2019). "Meet Russian Imperial officers who almost stopped the Bolsheviks". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Russian Civil War Polities". http://worldstatesmen.org/Russia_War.html

- ^ Bechhofer Roberts, Carl Eric (1921). In Denikin's Russia And The Caucasus, 1919-1920: Being A Record Of A Journey To South Russia, The Crimea, Armenia, Georgia, And Baku In 1919 And 1920. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Mediamax. "Հայաստանի կապերը Դենիկինի եւ Կոլչակի հետ" [Armenia's ties to Denikin and Kolchak]. Republic.Mediamax.am (in Armenian). Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ The YIVO encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe by YIVO institute for Jewish Research.

- ^ Florinsky, Michael T. (1961). "McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Russia and the Soviet Union". Encyclopedia of Russia and the Soviet Union. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Mayer, Arno J. (2000). The Furies. Princeton University Press. p. 520. ISBN 9780691090153. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ История советской России'; Ратьковский, И.С.; Ходяков, М.В.; Изд-во: СПб: Лань, 2001 г.; ISBN 5-8114-0373-9. С. 57

- ^ Klier, John Doyle; Lambroza, Shlomo (12 February 2004). Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521528511 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kenez, Peter, "The Ideology of the White Movement," Soviet Studies, 1980, no. 32. pp. 58–83. Christopher Lazarski, "White Propaganda Efforts in the South during the Russian Civil War, 1918-19 (The Alekseev-Denikin Period)," The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 70, No. 4 (Oct., 1992), pp. 688–707. Viktor G. Bortnevski, "White Administration and White Terror (The Denikin Period)," Russian Review, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Jul., 1993), pp. 354–366.

- ^ John Ernest Hodgson ("War Correspondent with the Anti-Bolshevik Forces"), "With Denikin's Armies: Being a Description of the Cossack Counter-Revolution in South Russia, 1918-1920", Temple Bar Publishing Co., London, 1932, pp. 54-56.

- ^ TIME (2 January 1939). "RUSSIA: White or Red". TIME. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Bigg, Claire (3 October 2005). "Russia: White Army General Reburied In Moscow". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Eighty-five years after fleeing into exile, General Anton Denikin was reburied with full honors at Moscow's Donskoy Monastery in a grand ceremony attended by some 2,500 people.

- ^ "Putin: 'You certainly should read' Anton Denikin's diary; specifically the part about 'Great and little Russia, Ukraine. He says nobody should be allowed to interfere between us. This is only Russia's - May 24, 2009". KyivPost. 24 May 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "The Forgotten History of Ukrainian Independence - Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung". www.rosalux.de. 21 March 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 364.

Sources

[edit]- The standard reference is Dimitry V. Lehovich, White Against Red - the Life of General Anton Denikin, New York, W.W. Norton, 1974. This book is also available in Russian in two versions: then abridged text is Belye Protiv Krasnykh, Moscow, Voskresenie publishers, 1992. The second, unabridged, is Denikin - Zhizn' Russkogo Ofitsera, Moscow, Evrasia publishers, 2004.

- Grey M. Bourdier J. Les Armes blanches. Paris, 1968

- Grey M. La campagne de glace. Paris. 1978

- Grey M. Mon père le géneral Denikine. Paris, 1985

- Peter Kenez Civil War in South Russia. 1918. The first Year of the Voluntary Army. Berkeley, Los Angeles, 1971

- Peter Kenez Civil War in South Russia. 1919-1920. The defeat of the Whites. Berkeley, 1972

- Luckett R. The White Generals: An Account of the White Movement in the South Russia. L., 1971

- (in Russian) Ипполитов Г. М. Деникин — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2006 (серия ЖЗЛ) ISBN 5-235-02885-6

External links

[edit]- Works by Anton Denikin at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Anton Denikin at the Internet Archive

- Anton Ivanovich Denikin. Biographies at Answers.com. Answers Corporation, 2006.

- Pogroms in Southern Russia; Massacres of Jews in Several Towns Follow Retreat of Denikin's Army; New York Times (February 26, 1920)

- Berkman, Alexander; "FASTOV THE POGROMED" from The Bolshevik Myth, New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925

- Evgenii Vladimirovich Volkov: Denikin, Anton Ivanovich, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Newspaper clippings about Anton Denikin in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1872 births

- 1947 deaths

- Burials at Donskoye Cemetery

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath

- Imperial Russian Army generals

- People from Warsaw Governorate

- People from Włocławek

- People of the Russian Civil War

- People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

- Recipients of the Gold Sword for Bravery

- Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 2nd class

- Recipients of the Order of St. George of the Third Degree

- Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd class

- Russian anti-communists

- Russian military personnel of the Russo-Japanese War

- Russian nationalists

- Nobility from the Russian Empire

- Russian people of World War I

- Russian Provisional Government generals

- Perpetrators of the White Terror (Russia)

- Perpetrators of pogroms in the Russian Civil War

- White Russian emigrants to France

- White Russian emigrants to the United States

- White movement generals