The Wrecking Crew (music)

The Wrecking Crew | |

|---|---|

Members of the Wrecking Crew employed for a session at Gold Star Studios in the 1960s Seated left to right: Don Randi, Al De Lory, Carol Kaye, Bill Pitman, Tommy Tedesco, Irving Rubins, Roy Caton, Jay Migliori, Hal Blaine, Steve Douglas, and Ray Pohlman | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1960s–1970s |

| Past members |

|

The Wrecking Crew, also known as the Clique and the First Call Gang, was a loose collective of American session musicians based in Los Angeles who played on many studio recordings in the 1960s and 1970s, including hundreds of top 40 hits. The musicians were not publicly recognized at the time, but were viewed with reverence by industry insiders. They are now considered one of the most successful and prolific session recording units in history.

Most of the players had formal backgrounds in jazz or classical music. The group had no official name in its early years, and when the name the Wrecking Crew was first used is a subject of contention. The name was in common use by April 1981 when Hal Blaine used it in an interview with Modern Drummer. The name became more widely known when Blaine used it in his 1990 memoir, attributing it to older musicians who felt that the group's embrace of rock and roll was going to "wreck" the music industry.

The unit coalesced in the early 1960s as the de facto house band for Phil Spector and helped realize his Wall of Sound production style. They became the most requested session musicians in Los Angeles, playing behind recording artists including Jan and Dean, Sonny & Cher, the Mamas and the Papas, the 5th Dimension, Frank Sinatra, and Nancy Sinatra. The musicians were sometimes used as "ghost players" on recordings credited to rock groups, such as the Byrds' debut rendition of Bob Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man" (1965), the first two albums by the Monkees, and the Beach Boys' 1966 album Pet Sounds.

The Wrecking Crew's contributions went largely unnoticed until the publication of Blaine's memoir and the attention that followed. The keyboardist Leon Russell and the guitarist Glen Campbell became popular solo acts, while Blaine is reputed to have played on more than 140 top-ten hits, including approximately 40 number-one hits. Other members included the drummer Earl Palmer, the saxophonist Steve Douglas, the guitarist Tommy Tedesco, and the keyboardist Larry Knechtel, who became a member of Bread. Blaine and Palmer were among the inaugural "sidemen" inductees to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000, and the Wrecking Crew was entirely inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum in 2007. In 2008, they were the subject of the documentary The Wrecking Crew.

Historical context

[edit]Recording practices in the 1960s

[edit]In the era when the Wrecking Crew was in demand, session players were usually active in local recording scenes concentrated in cities such as New York City, Nashville, Memphis and Detroit, as well as Los Angeles, the Wrecking Crew's base of operations, and smaller specialist recording locations such as Muscle Shoals.[1][2][3] Each local scene had its circle of "A-list" session musicians, such as the Nashville A-Team that played on numerous country and rock hits of the era, the two groups of musicians in Memphis, the Memphis Boys and Booker T. & the M.G.s with the Memphis Horns, the musicians who backed Stax/Volt recordings, and the Funk Brothers in Detroit, who played on many Motown recordings.[2][3]

At the time, multi-tracking equipment, though common, was less elaborate, and instrumental backing tracks were often recorded "hot" with an ensemble playing live in the studio.[4] Musicians had to be available "on call" when producers needed a part to fill a last-minute time slot.[5] Los Angeles was then considered the top recording location in the United States—consequently studios were constantly booked around the clock, and session time was highly sought after and expensive.[6] Songs had to be recorded quickly in the fewest possible takes.[3][7] In this environment, Los Angeles producers and record executives had little patience for needless expense or wasted time and depended on the service of reliable standby musicians who could be counted on to record in a variety of styles with minimal practice or takes, and deliver hits on short order.[3][5][8]

Musical backgrounds

[edit]The Wrecking Crew were the "go to" session musicians in Los Angeles during this era.[3][9] Its members were musically versatile but typically had formal backgrounds in jazz or classical music, and were exceptional at sight reading.[10] The talent of this group of "first call" players was used in almost every style of recording, including television theme songs, film scores, advertising jingles and many genres of American popular music from the Monkees to Bing Crosby.[11][12] Several of the Los Angeles recording studios in which the Wrecking Crew regularly appeared were Gold Star Studios, United Western Recorders built by Bill Putnam, Capitol Records' studios located at their tower on Vine Street, Columbia Records' Los Angeles complex, and the RCA recording facility, which was located on Sunset Boulevard near Wallichs Music City, a music store that often supplied instruments for L.A. session players.[13][14] Like all session musicians who worked in Los Angeles, the Wrecking Crew's members belonged to the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), Local 47, which represented their interests in areas such as pay scale and enforcement of regulations.[15]

Name

[edit]

The name "Wrecking Crew" was popularized by drummer and member Hal Blaine in his 1990 memoir, Hal Blaine and the Wrecking Crew.[16][17][18] Though the unit did not have an official moniker during their years of activity, Blaine has stated that the term was sometimes used disparagingly in the early 1960s by members of the industry's old guard of "coat and tie" session players, who felt that, with their penchant for wearing "t-shirts and jeans" to sessions and their embrace of rock and roll, they were going to "wreck" the music industry.[16][11] According to biographer Kent Hartman, "Some of the studio musicians I interviewed swear they heard it applied to themselves as early as 1963; others say it was later. One says it was never used at all."[19] Blaine's memoirs, and the attention that followed, cast new light on the Wrecking Crew's role in many famous recordings.[20]

Guitarist and bassist Carol Kaye has disputed Blaine's account of the name and stated, "We were never known as that. Sometimes we were called 'the Clique', but "the Wrecking Crew" is a Hal Blaine invented name for his own self-promotion in 1990 ..." Songfacts stated: "We couldn't find any references to 'The Wrecking Crew' in any publications from the era."[21] In response to Kaye's contention, Blaine denied that anyone had ever heard the name "The Clique".[22]

Formation of unit: 1957–1962

[edit]

The beginnings of the group can be traced to session musicians of the late 1950s including Irv Cottler, Earl Palmer, Howard Roberts, Hal Blaine[23] and a group headed by bassist and guitarist Ray Pohlman, sometimes referred to as the "First Call Gang".[24] Earl Palmer was originally from New Orleans and had recorded with many of the Crescent City's rhythm and blues musicians, such as Fats Domino.[23] He moved to Los Angeles in 1957, and in the 1960s played on hit records by artists such as Ike and Tina Turner, Glen Campbell, Jan and Dean, the Righteous Brothers, the Beach Boys, the Ronettes, the Everly Brothers, and Sonny & Cher.[23] Pohlman was one of the first session musicians in Los Angeles to use an electric bass in recordings, and by the early 1960s became highly sought after in rock recordings, playing on many records by Jan and Dean and the Beach Boys.[25]

In 1962, Phil Spector started a new label, Philles Records, and recorded the song "He's a Rebel", which would be credited to the Crystals.[26] He enlisted the aid of his high-school friend, saxophonist Steve Douglas, who was also working as a contractor in charge of recruiting musicians for recording sessions.[26] Douglas helped him corral the backing unit, which included Pohlman, guitarists Roberts and Tommy Tedesco, pianist Al De Lory, upright bassist Jimmy Bond, and Hal Blaine on drums.[26] They booked Studio A at Gold Star Studios, known for its deeply reverberant echo chambers, which became the preferred recording facility for Spector.[26] The unit became an essential component in developing his "Wall of Sound" style,[27] starting with "He's a Rebel" and a series of several more hits by the Crystals ("Da Doo Ron Ron" and "Then He Kissed Me") and other girl groups, such as the Ronettes ("Be My Baby" and "Baby, I Love You").[26] It was on these recordings that the Wrecking Crew emerged in their most recognizable form and became the most coveted session players in Los Angeles's thriving recording scene.[26][27] With them, Spector went on to produce other records by the Righteous Brothers ("You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'", "Ebb Tide", and "Unchained Melody") and Ike and Tina Turner ("River Deep – Mountain High").[26][nb 1]

Peak years: 1963–1971

[edit]After Spector, the Wrecking Crew worked with dozens of producers, such as Brian Wilson, Terry Melcher, Lou Adler, Bones Howe, Jimmy Bowen, and Mike Post.[28] As side players, they were teamed with artists as diverse as Jan & Dean, Bobby Vee, Nancy Sinatra, the Grass Roots, Simon & Garfunkel, Glen Campbell, the Partridge Family, David Cassidy (in his solo work), the Carpenters, John Denver and Nat King Cole.[29] During this heady period the unit worked long hours—15-hour days were not unusual—and were paid exceedingly well.[30][31] Carol Kaye commented, "I was making more money than the President."[30]

Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys produced and co-wrote many of his band's most famous tracks and used the Wrecking Crew's talents extensively in the mid-1960s, including on songs such as "Help Me, Rhonda", "California Girls", and "Good Vibrations" as well as the albums Pet Sounds and Smile.[32][22][33] Some reports falsely claim that the Wrecking Crew replaced the Beach Boys on record after their first few hits;[34][35][36] however, this misconception derived from incomplete written documentation of the recording sessions.[34][36] After audio documentation surfaced, it was revealed that the Beach Boys' first ten albums leading up to Pet Sounds and Smile were, by and large, self-contained efforts, and the band members played instruments on most of their singles and key album tracks.[34][35][nb 2] It was not until the 1965 album The Beach Boys Today! that Wrecking Crew musicians began to figure heavily on the band's studio recordings, an arrangement that lasted until 1967.[35][34]

Members of the Wrecking Crew served as "ghost players" on the first single by the Byrds, "Mr. Tambourine Man", because Columbia Records—namely, producer Terry Melcher—did not feel that the group (except for Roger McGuinn, who played guitar on the single) were seasoned enough to deliver the kind of perfect take needed, particularly in light of the limited time and budget allocated to the newly signed and unproven group—on a label that was only just beginning to embrace rock.[39][40]

Lou Adler was one of Los Angeles' top music executives and produced records by acts such as Jan and Dean and the Mamas & the Papas, which were often backed by the Wrecking Crew, as on "California Dreamin'" and "Monday, Monday".[41] Bones Howe had worked as an engineer under Adler and used the Wrecking Crew when he produced hits by the Association (including "Windy", "Everything That Touches You", and "Never My Love") and the 5th Dimension (including "Up, Up and Away", "Stoned Soul Picnic", and "Aquarius").[42][30]

Sonny and Cher recorded several Wrecking Crew-backed hits including "I Got You Babe" and "The Beat Goes On", which were produced by Sonny Bono, who had previously worked as Phil Spector's aide.[43] Many of Cher's solo records in the 1960s and early 1970s featured the backing of the Wrecking Crew, such as "Gypsys, Tramps & Thieves" produced by Snuff Garrett in 1971.[44][29] Jimmy Bowen produced Frank Sinatra's "Strangers in the Night" in 1966 and Mike Post produced Mason Williams' 1968 hit "Classical Gas", both of which were backed by members of the Wrecking Crew.[45]

Wrecking Crew members backed the Everly Brothers on their "The Hit Sound of the Everly Brothers" (1967) and "The Everly Brothers Sing" (1968) albums.[46]

Rick Nelson used many Wrecking Crew members in various combinations, mostly during the mid-1960s, including Earl Palmer, Joe Osborn, James Burton, Tommy Tedesco, Howard Roberts, Billy Strange, Al Casey, Dennis Budimir, Glen Campbell, Don Randi, Mike Melvoin, Ray Pohlman, Chuck Berghofer, Victor Feldman, Frank Capp, and Jim Gordon.[47]

Musicians

[edit]Bass, drums, and percussion

[edit]

Carol Kaye provided an exception to the predominantly male world of Los Angeles session work in the 1960s.[48] Originally a guitarist, she began doing session work in Los Angeles in the late 1950s, playing behind Ritchie Valens on "La Bamba" and in the 1960s becoming a regular contributor on Phil Spector's recordings as well as on Beach Boys songs, such as "Help Me, Rhonda" and their subsequent Pet Sounds and Smile LPs.[49][50] Ray Pohlman, who had assumed an early leadership position in the Wrecking Crew, became the musical director for the Shindig! TV show in 1965, resulting in reduced studio work from that point on.[24][25] After Pohlman's move to television, Kaye increasingly concentrated on the electric bass, becoming one of the few female "first call" players on the L.A. scene.[51] She supplied the signature bass line in Sonny and Cher's "The Beat Goes On" released in 1967.[52][53] Kaye was often teamed with Pohlman on pop music sessions (e.g. those for the Beach Boys) since it was a common practice at that time to reinforce the sound by "doubling" certain instruments like the bass, and producers and arrangers often recorded the bass parts with an acoustic and an electric bass playing together. Kaye would become known as one of the most prolific and widely heard bass guitarists, playing on an estimated 10,000 recordings in a career spanning more than 50 years.[54]

Joe Osborn played bass on numerous Wrecking Crew-backed songs, such as Glen Campbell's "By the Time I Get to Phoenix", the Mamas & the Papas' "California Dreamin'", Richard Harris' "MacArthur Park", and the 5th Dimension's "Up, Up and Away".[55] Other notable electric bassists who played with the Wrecking Crew were Bill Pitman, Max Bennett, Red Callender, Chuck Rainey, and Bob West, as well as Jimmy Bond, Lyle Ritz, and Chuck Berghofer, who played acoustic upright bass.[56][57][58]

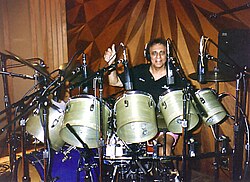

Drummer Earl Palmer contributed to a handful of hits in the 1960s with the Wrecking Crew, including Phil Spector-produced tracks such as Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" in 1964, and Ike and Tina Turner's "River Deep – Mountain High" in 1966.[59][60][61] Hal Blaine, with his abundance of musical skills, personality, and charisma, is also mentioned as having a prominent role in the Wrecking Crew's success during their heyday.[62][18][63][nb 3] Though he had played primarily big band and jazz, he took a job in Tommy Sands' rockabilly group in the late 1950s, discovering a newfound appreciation for rock and roll, which by the beginning of the new decade led to session work in Los Angeles studios, where he became acquainted with Earl Palmer and saxophonist Steve Douglas.[65] Blaine played on Elvis Presley's 1961 hit "Can't Help Falling in Love".[17] Shortly thereafter, he began playing on sessions for Phil Spector, quickly becoming the producer's preferred drummer, and, along with Earl Palmer, became one of the two top session drummers in Los Angeles.[66] Blaine is reputed to have played on over 140 top ten hits including approximately 40 No. 1 hits, such as "I Got You Babe" by Sonny & Cher, "Mr Tambourine Man" by the Byrds, and "Strangers in the Night" by Frank Sinatra, as well as numerous others and has been mentioned by Drummerworld as perhaps the most prolific recording drummer in history.[17][67] Jim Gordon began as an understudy of Blaine, but with the passage of time emerged as a first call player in the Wrecking Crew, playing on parts of the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds album and on hits such as "Classical Gas" and "Wichita Lineman".[17][68][nb 4]

Other drummers who played in the Wrecking Crew were Frank Capp, John Clauder, Forrest Draper[70] and Joe Porcaro.[71][58][72] Gary Coleman played vibraphone and a variety of percussion instruments and contributed to works such as the soundtrack of the musical Hair and Simon & Garfunkel's Bridge Over Troubled Water album.[73] Some of the other Wrecking Crew percussionists were Julius Wechter, Milt Holland, Gene Estes, and Victor Feldman.[73][58] Drummer Jim Keltner is sometimes mentioned in connection with the Wrecking Crew, because he befriended Hal Blaine in the 1960s and would later play with the Wrecking Crew on John Lennon's Rock 'n' Roll album recorded in 1973, but he is more often associated with the later generation of session players who eclipsed the Wrecking Crew in terms of popularity during the 1970s.[nb 5]

Guitars and keyboards

[edit]

Guitarist and sometimes bassist Bill Pitman factored prominently in much of the Wrecking Crew's work.[76] For a brief time in the late 1950s he provided guitar lessons for a young Phil Spector, before Spector formed the Teddy Bears, who went on to record the surprise hit "To Know Him Is to Love Him" in 1958.[77] Pitman ended up playing on Spector-produced records in the 1960s such as "Be My Baby" by the Ronettes.[78] He can be heard on numerous hits from the period such as "The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena)" by Jan & Dean, and "Mr. Tambourine Man" by the Byrds.[79] Tommy Tedesco, born in an Italian family in Niagara Falls, New York, was another one of the Wrecking Crew's most renowned guitarists, playing along with Pitman on "Be My Baby" and "The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena)", as well as on the Champs "Limbo Rock".[80] He provided the flamenco-influenced guitar licks in the 5th Dimension's "Up and Away" as well as the guitar intro to the popular M*A*S*H theme.[81][82] Billy Strange was one of the top guitarists with the Wrecking Crew and played on hits such as "The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena)" and the Beach Boys' version of "Sloop John B".[83] In addition to playing sessions in Memphis, guitarist James Burton often recorded with the Wrecking Crew in Los Angeles in the 1960s.[84][85][86]

Though Glen Campbell became better known as a highly successful country music artist in his own right, he played guitar in the Wrecking Crew during the 1960s and appeared along with them on several of the Beach Boys' classics of the period such as "I Get Around" and "Help Me Rhonda".[87] He and Hal Blaine appeared as members of Steve McQueen's character's band in the film Baby the Rain Must Fall (1965) featuring an extremely clear moment of Campbell standing behind McQueen, but both Campbell and Blaine were uncredited in the film. In 1965 he toured with the Beach Boys, and in 1966 he and the Wrecking Crew played on the Pet Sounds album.[88][nb 6] Campbell enlisted the Wrecking Crew as a backup unit on many of his own solo records during the 1960s, such as on "Gentle on My Mind", and on two songs written by Jimmy Webb, "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" and his single "Wichita Lineman".[90]

The Wrecking Crew's ranks included a circle of keyboardists who contributed piano and organ parts to many of the famous songs of the era. Larry Knechtel, later in Bread, was a multi-instrumentalist who played keyboards on "California Dreamin'", "Bridge Over Troubled Water" and "Classical Gas", as well as upright bass on "Eve of Destruction" and electric bass on Byrds' "Mr. Tambourine Man".[91] Mike Melvoin, a classically trained pianist with an English degree from Dartmouth College, played organ and piano on many tracks on the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, played organ on "Good Vibrations", and performed on keyboards on many of the sessions for the Beach Boys' never-completed SMiLe album.[92] Don Randi contributed the piano part on Barry McGuire's 1965 hit "Eve of Destruction".[93] Before becoming a solo artist, Leon Russell was a regular member of the Wrecking Crew and played on the Ronettes' "Be My Baby", and Jan & Dean's "The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena)."[94] New Orleans' Mac Rebennack (later Dr. John) did session work with the Wrecking crew while living in Los Angeles in the mid-1960s.[95] Mike (Michel) Rubini was the son of Jan Rubini, a classical violinist, and initially played concert piano, but later became enamored with R&B and switched to playing popular music, eventually becoming a member of the Wrecking Crew and playing on hits such as Sonny & Cher's "The Beat Goes On" and Frank Sinatra's "Strangers in the Night".[96]

Brass, woodwinds, harmonica, and backing vocals

[edit]Saxophonist Steve Douglas, who attended Fairfax High School with Phil Spector in the 1950s, got a call in 1962 to play on Spector's debut recording as a producer, "He's a Rebel", and would, from then on, become a regular fixture with the Wrecking Crew.[97][98] Years later, in 1978, Douglas played on Bob Dylan's 1978 "Street-Legal" album and accompanied Dylan on tour that year as part of his eight piece backing band.[98][99] Jim Horn played both saxophone and flute, and contributed parts to numerous tracks with Wrecking Crew, such as in the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" and Frank Sinatra's "Strangers in the Night".[100][101] He played flute in the Beach Boys' "God Only Knows" and "Good Vibrations" and would later become a member of John Denver's backing band.[101] Plas Johnson provided the saxophone line in "The Pink Panther Theme" in the Champs' 1962 instrumental version of "Limbo Rock".[102] Nino Tempo, who along with his sister Carol (under her stage name April Stevens) had scored a U.S. number 1 hit song in 1963, "Deep Purple", was also a member of the Wrecking Crew and played saxophone in the Ronettes' "Be My Baby" and later appeared on John Lennon's Rock 'n' Roll album.[103][104]

Other saxophonists who played sessions with the Wrecking Crew were Jackie Kelso, Jay Migliori, Gene Cipriano, Bill Green, and Allan Beutler.[105] On trombone were Richard "Slyde" Hyde, Lew McCreary, and Dick Nash [105][106] and on trumpet Bud Brisbois, Roy Caton, Chuck Findley, Ollie Mitchell, and Tony Terran.[105][107] Tommy Morgan played harmonica on Wrecking Crew-backed tracks such as "The Little Old Lady (from Pasadena)".[108] When backing vocals were needed the Ron Hicklin Singers were called in.[107]

T.A.M.I. Show (1964)

[edit]Several members of the Wrecking Crew played in the house band for 1964's T.A.M.I. Show, which was captured on film and sent to theaters around the country.[109] Seen in camera shots showing the right-hand side of the stage are musical director Jack Nitzsche, Hal Blaine, Jimmy Bond, Tommy Tedesco, Bill Aken, Glen Campbell, Lyle Ritz, Leon Russell, Plas Johnson, among others, all providing incidental music and backing for many of acts such as Chuck Berry, the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and Lesley Gore.[109][110][111]

1970s–2010s

[edit]Diminished output

[edit]The Wrecking Crew's level of success could not be maintained indefinitely, and their services eventually fell out of demand.[112] Kent Hartman cites several factors in the Wrecking Crew's demise, beginning as far back as 1968 when the unit was at their peak of popularity: "By the middle of 1968, popular music was changing once again. In fact it was getting downright heavy. In the aftermath of the recent Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. slayings, the bloody Tet Offensive in Viet Nam, and the ever-growing level of campus unrest at universities around the country, Top 40 radio gradually began to lose step with the times."[113] Hartman mentions that the runaway success that year of Richard Harris' elaborate seven-minute epic hit, "MacArthur Park", written by Jimmy Webb and featuring the Wrecking Crew's intricate backing, might have been another seed in their eventual decline:

Webb's creation additionally generated another unexpected consequence, one that would begin to subtly affect the Wrecking Crew's livelihood. Because the song had broken through the AM radio barrier, it had suddenly made it okay for lengthier songs to make the playlist. And the longer each song, the fewer minutes left during each hour for the station to play other songs. That was the unfair, mathematical irony of the whole equation; the Wrecking Crew had just played their hearts out on an all-time award-winning hit, yet its very success contributed toward a drop in the total number of songs making it on the air. And with fewer songs finding airtime, there gradually evolved a diminishing number of rock-and-roll recording dates for them to play on.[114]

The Wrecking Crew remained in demand in the early 1970s, even enjoying several hits, but by the end of 1973 they began to experience a downturn in bookings, as a series of changes in the recording industry began to take hold.[115] Unlike earlier bands/artists such as the Monkees, the Grass Roots, the Partridge Family and David Cassidy that often utilized the Wrecking Crew for backing tracks (and as a backing band for Cassidy's earliest concert tours of America in 1971/2), rock groups in the early to mid 1970s began to stipulate in their recording contracts that they be allowed to play their own instruments on records.[116] Younger session players such as Larry Carlton, Andrew Gold, Danny Kortchmar, Waddy Wachtel, Russ Kunkel, Jeff Porcaro, Leland Sklar, and Jim Keltner had a more contemporary sound, better-suited to the changing musical tastes of the decade.[74] By the mid-1970s, technological advances such as 16-track and 24-track tape recording machines and automated large-format multi-channel consoles made it viable for instruments to be recorded, often close-miked, onto separate tracks individually, reducing the need to hire ensembles to play live in the studio.[117][118][119] Synthesizers could approximate the sound of practically any instrument. Eventually, drum machines would become the norm, which could be specially programmed to keep beats in place of a drummer or be used for click tracks played in musicians' headphones, making it easier to overdub or re-record any part in-synch and achieve a more uniform and consistent tempo.[120][121]

Post–Wrecking Crew careers

[edit]In 1969, after scoring hits as a solo artist such as "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" and "Wichita Lineman", Glen Campbell left the Wrecking Crew.[122] [123] Carol Kaye, exhausted from the constant pressure of the L.A. recording scene, went on to other musical endeavors.[123] According to guitarist Bill Pitman, "You leave the house at seven o'clock in the morning, and you're at Universal at nine till noon; now you're at Capitol Records at one, you just got time to get there, then you got a jingle at four, then we're on a date with somebody at eight, then the Beach Boys at midnight, and you do that five days a week ... jeez, man, you get burned out."[95] Campbell went on to become one of country music's most popular performers during the 1970s with hits such as "Rhinestone Cowboy" and the Allen Toussaint-penned "Southern Nights".[124]

By the mid-1970s many of the Wrecking Crew's members scattered and drifted into different spheres. Some members, such as Carol Kaye, Tony Terran, Gary L. Coleman, Earl Palmer and Tommy Tedesco, switched to television and motion picture soundtrack work.[125] Leon Russell and Mac Rebennack (as Dr. John) both went on to become successful solo artists and songwriters, enjoying hit singles and albums during the 1970s.[126][127] Jim Keltner went on to a successful career as a session drummer for much of the 1970s–90s; he played in Ringo Starr's All-Starr band and was the drummer on both albums by the supergroup Traveling Wilburys, where he is credited as "Buster Sidebury".[128][129] Beginning in 1973 he hosted a regular weekly jam session at Los Angeles clubs called "the Jim Keltner Fan Club" frequented by many of the younger L.A. session musicians of the time (Danny Kortchmar, Russ Kunkel, Waddy Wachtel, Leland Sklar, and Jeff and Steve Porcaro).[130]

The unit did a brief, but ill-fated reunion session with Phil Spector in 1992. In 2001, members of The Wrecking Crew reunited in the studio with David Cassidy to recreate Cassidy's hit songs from the 1970s, both solo and with The Partridge Family. These recordings resulted in the album Then and Now which was hugely successful internationally and went platinum in 2002. More recently, they backed Glen Campbell in his song "I'm Not Gonna Miss You" taken from the soundtrack of the 2015 documentary Glen Campbell: I'll Be Me.[131]

Legacy

[edit]The Wrecking Crew backed dozens of popular acts and were one of the most successful groups of studio musicians in music history.[132][133] According to Kent Hartman, "... if a rock-and-roll song came out of an L.A. recording studio from between about 1962 and 1972, the odds are good that some combination of the Wrecking Crew played the instruments. No single group of musicians has ever played on more hits in support of more stars than this superbly talented—yet virtually anonymous group of men (and one woman)."[134] According to The New Yorker, "The Wrecking Crew passed into a history that it largely created, imperfectly acknowledged but perfectly present in hundreds of American pop songs known to all."[95] In 2008, the Wrecking Crew were featured in the documentary film The Wrecking Crew, directed by Tommy Tedesco's son, Denny Tedesco.[135] In 2014, its musicians were depicted in the Brian Wilson biopic Love & Mercy (playing the instrumental track Pet Sounds).[136]

Two of their members, drummers Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer, were among the inaugural "sidemen" inductees to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000, and the entire Wrecking Crew was inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame in 2007.[137][138][139] In 2010, Blaine was elected into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame.[140]

List of members

[edit]Sources: Kent Hartman (The Wrecking Crew)[141] and Robert Lloyd ("Time of the Session"; LA Weekly)[58]

- Electric bass: Max Bennett, Carol Kaye, Larry Knechtel, Joe Osborn, Bill Pitman, Ray Pohlman

- Double bass (upright bass): Chuck Berghofer, Jimmy Bond, Red Callender, Lyle Ritz

- Drums: Hal Blaine, Jim Gordon, Jim Keltner, Earl Palmer, Joe Porcaro

- Guitar: Vinnie Bell, Dennis Budimir, James Burton, Glen Campbell, Al Casey, Jerry Cole, Mike Deasy, Carol Kaye, Barney Kessel, Bill Pitman, Ray Pohlman, Howard Roberts, Louie Shelton, P.F. Sloan, Billy Strange, Tommy Tedesco

- Keyboards: Glen D. Hardin, Clare Fischer,[142] Mac Rebennack, Al De Lory, Larry Knechtel, Mike Melvoin, Don Randi, Mike (Michel) Rubini, Leon Russell

- Percussion: Larry Bunker, Frank Capp, Gary Coleman, Victor Feldman, Milt Holland, Joe Porcaro

- Vibraphone & Marimba: Julius Wechter, Terry Gibbs

- Other Percussion: Jingle Bells and Tambourine Sonny Bono[143][nb 7]

- Saxophone: Gene Cipriano, Steve Douglas, Jim Horn, Plas Johnson, Jackie Kelso, Jay Migliori, Nino Tempo

- Trombone: Lew McCreary,Richard "Slyde" Hyde, Dick Nash, Lou Blackburn

- Trumpet: Bud Brisbois, Roy Caton, Chuck Findley, Ollie Mitchell, Tony Terran

- Flute: Jim Horn

- Harmonica: Tommy Morgan

- Vocals: Ron Hicklin Singers often performed backup vocals on many of the same songs on which the Wrecking Crew had played instrumental tracks.

- Conductor and arranger: Jack Nitzsche

Blaine, Osborn and Knechtel were often collectively referred to as the Hollywood Golden Trio.[145]

Selected recordings

[edit]Compilations

[edit]- The Wrecking Crew (2015, RockBeat; 4-CD set)[154]

See also

[edit]- Booker T. & the M.G.'s

- The Funk Brothers

- MFSB

- Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section

- The Nashville A-Team

- Salsoul Orchestra

- The Section

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ In 1977 Spector would once again use the Wrecking Crew to do the backing tracks on Leonard Cohen's fifth album, Death of a Ladies' Man.[26]

- ^ For example, although it is often reported that drummer Dennis Wilson was replaced on record by studio musicians,[34][37] his drumming is documented on a number of the group's singles, including "I Get Around", "Fun, Fun, Fun", and "Don't Worry Baby".[38]

- ^ Blaine (born Harold Simon Belsky in Holyoke, Massachusetts) spent most of his childhood in Hartford, Connecticut, but his family moved to southern California in the late 1940s where he became a professional drummer.[64]

- ^ He would eventually play in Derek and the Dominos in the early 1970s.[69]

- ^ Its release was delayed until 1975 due to numerous problems legal and otherwise, such as when producer Phil Spector ran off with the sessions' tapes.[74][75]

- ^ Campbell and the Wrecking Crew played on "Strangers in the Night" by Frank Sinatra.[89]

- ^ Max Weinberg in his book "The Big Beat" does include Bono in a list of members of the Wrecking Crew as "percussion" and Bono appears in the photograph labeled, "The Wrecking Crew" on p. 79 of the book.[144]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Savona, Anthony (2005). Console Confessions: The Great Music Producers in Their Own Words (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-0-87930-860-5.

- ^ a b Source A: "The Nashville 'A' Team". Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016. Source B: "Motown Sound: Funk Brothers". Motown Museum. Retrieved January 20, 2016. Source C: Brown, Mick (October 25, 2013). "Deep Soul: How Muscle Shoals Became Music's Most Unlikely Hit Factory". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Hartman 2012, pp. 2–5, 110, 175–176.

- ^ "Recording studios – Why Can Recordings Made in the e.g. 1960s Sound Good in 2011?". NAIM. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Andrews, Evan (July 1, 2011). "Top 10 Session Musicians and Studio Bands". Toptenz.net. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Byrds: Who Played What?". JazzWax. September 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Farber, Jim (March 9, 2015). "The Wrecking Crew Documentary Profiles the Secret Players Behind Many 1960s and '70s Rock Hits". Daily News. New York. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Laurier, Joanne (November 14, 2015). "The Wrecking Crew: The "Secret Star-Making Machine" of 1960s Pop Music". World Socialist Website. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Ashlock, Alex (April 20, 2012). "The Musicians Behind The Great Bands That Got The Credit". WBUR-FM. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Men Behind the Music: Session Musicians of the 60s and 70s". The Peachiest.com. November 1, 2015. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Rapka, Linda (May 28, 2008). "L.A. Studio Musicians of the '60s Profiled in New Documentary". Los Angeles: The Overture, official publication of Professional Musicians, Local 47. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "The Wrecking Crew". Plymouth, MA: Creative Audio Works. January 5, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 50, 69, 98, 116–118, 150, 253, photo section: p. 6.

- ^ Kubernik, Harvey. "The Wrecking Crew". Record Collector. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 25, 69–70, 72, 147, 246, 250–251.

- ^ a b Hartman 2012, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d "Hal Blaine Biography". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Featured Musician: Hal Blaine". Drummer Cafe. Drummer Cafe.com. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Wiser, Carl. "Carol Kaye: Songwriter Interviews". Songfacts. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Pinnock, Tom (June 8, 2012). "The Making of Good Vibrations". Uncut.

- ^ a b c Perrone, Pierre (September 22, 2008). "Earl Palmer: Musician praised by Little Richard as 'the greatest session drummer of all time'". The Guardian UK. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Unterberger, Richie. "Carol Kaye". Richie Unterberger. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Ray Pohlman". AlbumLinerNotes.com. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hartman 2012, pp. 48–54, 91, 111–112.

- ^ a b Blaine & Goggin 1990, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 98–99, 101–102 (Melcher), 144–157 (Wilson), 70, 122–123 (Adler), 206–208, 222 (Howe), 130–139 (Bowen).

- ^ a b Niesel, Jeff. "Film Spotlight: The Wrecking Crew". Cleveland Scene. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c Elder, Sean (March 14, 2015). "Behind the Music Behind the Music: 'Wrecking Crew' Played Pop's Biggest Hits". Newsweek. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Jagger, Juliette (February 19, 2015). "The Wrecking Crew Played On All Your Favorite 60s And 70s Songs (Seriously)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 144–157, 262.

- ^ Hartman, Kent (February 13, 2012a). "The Band Behind the Beach Boys". Esquire. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Slowinski, Craig (2006). "Introduction". beachboysarchives.com. Endless Summer Quarterly. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Stebbins, Jon (2011). The Beach Boys FAQ: All That's Left to Know About America's Band. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4584-2914-8.

- ^ a b Wong, Grant (January 3, 2022). "Brian Wilson Isn't the Type of Genius You Think He Is". Slate.

- ^ Orme, Mike (July 8, 2008). "Pacific Ocean Blue: Legacy Edition". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Boyd, Alan; Linette, Mark; Slowinski, Craig (2014). Keep an Eye on Summer 1964 (Digital Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records. (Mirror)

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 19, 98–99, 101–102.

- ^ Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of The Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 70, 122–123.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 206–208, 222.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 88–95, 162–165205.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 263.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 130–139, 190–193, 195.

- ^ Down in the Bottom, The Everly Brothers, The Country Rock Sessions 1966-1968, CD, Cherry Red Records, London, England, liner notes, 2020

- ^ Nelson, Rick, Rick Nelson: Legacy, Box set, Capitol Records Inc., 72435-29521-2-0, Hollywood, CA, 2000, liner notes

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 164.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 52, 54, 144–145.

- ^ Bright, Kimberly J. (June 12, 2013). "Carol Kaye is Paul McCartney's Favorite Bass Player, He just Doesn't Know it was Her". Dangerous Minds.net. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 162–163.

- ^ "'The Beat Goes On' by Sonny and Cher". Songfacts. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ Berklee College of Music (October 18, 2000). "Berklee Welcomes Legendary Studio Bassist Carol Kaye". Archived from the original on September 10, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2007.

Kaye is the most recorded bassist of all time, with 10,000 sessions spanning four decades.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 123, 178–180, 182, 212–213.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 51, 54, 56, 71–72, 100, 123, 125, 134, 153–154, 167, 178, 165, 180, 182, 212–213, 207–208, 222–223, 229, 259.

- ^ Blaine & Goggin 2010, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Lloyd, Robert (April 8, 2004). "Time of the Session". LA Weekly. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Noland, Claire (September 21, 2008). "Earl Palmer:Legendary Session Drummer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ ""Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" 1964–1965". The Pop History Dig. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Ike & Tina Turner: River Deep-Mountain High (Review)". AllMusic. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Miller, Michael (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Playing Drums. Alpha Books. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-59257-162-8.

hal blaine earl palmer top session drummer.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 11–12, 42.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 42–46.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 51, 54, 56.

- ^ "Hal Blaine". Drummerworld. Drummerworld.com. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 233–236.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 233–243.

- ^ "Forrest Draper". IMDB. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 56, 163.

- ^ "John Clauder". NAMM. March 27, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ a b Hartman 2012, pp. 192–193, 220–223, 226, 245.

- ^ a b Hartman 2012, p. 248.

- ^ "Rock 'N' Roll". The Beatles' Bible. The Beatles Bible. August 22, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 35–36, 56, 71–72, 100.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 36, 41–42.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 56.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 56, 71–72, 100.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 51, 30, 71–72.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 182.

- ^ Leonard, Michael (December 26, 2013). "Tommy Tedesco: The Most Famous Guitarist You've Never Heard Of". Gibson. Gibson Brands, Inc. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 71–72, 151.

- ^ Roberts, Jeremy (March 6, 2014). "Louisiana Guitar Slinger James Burton Revisits Rockin' Nights with Rick Nelson". Press Pass. Presspass Blog. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 176.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (July 5, 2011). "The Wrecking Crew: the Inside story of LA's Session Giants". Music Radar. Quay House, The Ambury, Bath: Future Publishing Limited. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 59, 144–145.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 59–60, 154.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 133–134, 138–139.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 183–184 186, 199–201, 204–205.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 1–2, 100–101, 120, 123, 167, 182, 192–193, 199, 208, 212, 222–224, 226–227.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 245–247.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 56, 120, 254.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 56, 71–72, 100, 147, 233.

- ^ a b c "The Session Musicians Who Dominated Nineteen-Sixties Pop". New Yorker. December 3, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 104–105, 111, 134–137, 162–163.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 49–50, 52, 56, 254.

- ^ a b "Steve Douglas". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. 2003. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "Steve Douglas Is Dead; Rock Saxophonist, 55". New York Times. April 22, 1993. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 254.

- ^ a b Wardlaw, Matt (April 19, 2013). "Legendary Session Man Jim Horn On Working With John Denver And Getting Inside The "Genius" Of Brian Wilson". Pop Dose. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 30, 125.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 55–57, 245.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Nino Tempo". AllMusic. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c Hartman 2012, pp. 254, 259.

- ^ "The Wrecking Crew". Varga. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Cosper, Alex (March 27, 2015). "History of the Wrecking Crew Musicians". Playlist Research. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 71–72, 259.

- ^ a b Hartman 2012, p. 125.

- ^ Remnick, David (July 30, 2014). "The Possessed: James Brown in Eighteen Minutes". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Vincent, Alice (February 17, 2015). "Lesley Gore: Nine Things You Didn't Know". Telegraph Media Group Limited. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 212.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 212–215.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 247.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 148, 253.

- ^ "Technology and the Audio Engineer Part II". MPG: Music Production School. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Rumsey, Francis; McCormick, Tim (2014). "Five". Sound and Recording: Applications and Theory (7th ed.). New York and London: Focal Press, Taylor and Francis Group. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-415-84337-9.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 148.

- ^ "In Search of the Click Track". Music Machinery. March 2, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 178–180, 183–186, 199–201, 204–205, 216–217.

- ^ a b Hartman 2012, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Glen Campbell: Artist Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 149.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Unerberger, Richie. "Dr. John: Artist Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Ringo Starr: Ringo Starr and his All-Starr Band". The Band History. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Jim Keltner ..." Drummerworld. Drummerworld.com. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Flans, Robyn (October 1, 2014). "When Sessions Reigned Supreme: The Players, Studios from L.A.'s Golden Age". Mix. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Ayers, Mike (February 19, 2015). "Oscars 2015: The Story Behind Glen Campbell's 'I'm Not Gonna Miss You'". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 2–5, 256.

- ^ Hartman, Kent (February–March 2007). "The Wrecking Crew". American Heritage. Vol. 58, no. 1. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (March 12, 2015). "Film Review: 'The Wrecking Crew'". Variety.

- ^ Visci, Marissa (June 10, 2015). "Here's What's Fact and What's Fiction in Love & Mercy, the New Biopic About Brian Wilson". Slate.

- ^ "The 2000 Induction Ceremony". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. March 6, 2000. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Gilbert, Calvin (November 27, 2007). "Unsung Heroes Honored at Musicians Hall of Fame Induction". Country Music Television. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008.

- ^ "The Wrecking Crew". Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum. November 2007. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "Modern Drummer's Readers Poll Archive, 1979–2014". Modern Drummer. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 259.

- ^ Dorff, Steve; Freedman, Colette (2017). I Wrote That One, Too : A Life in Songwriting from Willie to Whitney. Montclair, NJ: Backbeat Books. pp. 65-66. ISBN 9781495077296.

- ^ Hartman 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Weinberg, Max. The Big Beat: Conversations with Rock's Great Drummers" Billboard Books, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York, 1991 p.76, & p.79

- ^ Small, Mark. "Score: 'Bridge Over Troubled Water'". Berklee College of Music. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Hartman 2012, pp. 49, 51–55, 57–58, 71–72, 93–95, 98–102, 112–113, 120–124, 126–127, 134–139, 152, 162–163, 164–165, 169, 181–182, 185–186, 191–195, 198–201, 203–205, 207, 212–214, 222–226, 228–233, 249, 251–252, 261–263 – all songs mentioned in Hartman, except for those with other citation presented next to song entry.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits, Billboard Books, New York, 1992

- ^ Betts, Graham (2004). Complete UK Hit Singles 1952–2004 (1st ed.). London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-717931-6.

- ^ Blaine & Goggin 1990, p. xviii.

- ^ Mersereau, Bob (2015). The History of Canadian Rock 'n' Roll. Backbeat Books. p. 50. ISBN 9781480367111.

- ^ Tedesco, Denny (Director). The Wrecking Crew (DVD extras) (DVD).

- ^ Bosso, Joe (October 26, 2011). "Carol Kaye: My 10 Greatest Recordings of All Time". Music Radar. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "Phonograph Recording Contract Blank - American Federations Of Musicians" (PDF). Wrecking Crew Film. November 13, 1967.

- ^ Prince, Patrick (September 5, 2015). "Music release highlights for September 2015". Goldmine Magazine: Record Collector & Music Memorabilia. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

General and cited references

[edit]- Blaine, Hal; Goggin, David (1990). Hal Blaine and the Wrecking Crew: The Story of the World's Most Recorded Musician (1st ed.). Emeryville, CA: Mix Books. ISBN 978-0-918371-01-0.

- Blaine, Hal; Goggin, David (2010). Schwartz, David M. (ed.). Hal Blaine and The Wrecking Crew (3rd ed.). Rebeats Publications. ISBN 978-1-888408-12-6.

- Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of The Byrds' Gene Clark. Hal Leonard Corporation/Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- Hartman, Kent (2012). The Wrecking Crew: The Inside Story of Rock and Roll's Best-Kept Secret (1st ed.). Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-61974-9.

- Miller, Michael (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Playing Drums. Alpha Books. ISBN 978-1-59257-162-8.

- Rumsey, Francis; McCormick, Tim (2014). Sound and Recording: Applications and Theory (7th ed.). New York and London: Focal Press, Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-84337-9.

- Savona, Anthony (2005). Console Confessions: The Great Music Producers in Their Own Words (1st ed.). San Francisico: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-860-5.

External links

[edit]- The Wrecking Crew discography at Discogs

- The Wrecking Crew at IMDb