W & J Galloway & Sons

| |

| Industry | Engineering |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | William & John Galloway |

| Founded | 1790 |

| Founder | William Galloway |

| Defunct | 1933 |

| Fate | Defunct |

| Successor | Hick, Hargreaves & Co. Ltd. |

| Headquarters | , England |

Key people | John Galloway (Inventor) |

| Products | Steam engines Boilers for steam engines |

W & J Galloway and Sons was a British manufacturer of steam engines and boilers based in Manchester, England. The firm was established in 1835 as a partnership of two brothers, William and John Galloway. The partnership expanded to encompass their sons and in 1889 it was restructured as a limited liability company. It ceased trading in 1932.

The Galloway brothers had been apprenticed to another partnership involving their father, a maker of waterwheels and gearing for mills, before setting up in business on their own account. Their firm grew to be a specialist producer of steam engines and industrial boilers with a worldwide customer base and a reputation for ingenuity. Their products were used in such diverse areas as electricity generation[1] and refrigeration.[2] The business grew with the increasing application of steam power in industry, and it died with industry's move to the application of electric power.

History

[edit]Galloway, Bowman and Glasgow

[edit]William Galloway was born on 5 March 1768 at Coldstream in the Scottish Borders, became a millwright and moved to Manchester in 1790.[3] He was one of many Scots who moved to England seeking to gain from the rapid expansion of industry there; others included William Murdoch and James Watt, who settled in Birmingham, and fellow settlers in the Manchester area, John Kennedy, James McConnel and the cotton-spinning brothers, Adam and George Murray.[4][5]

He set up business at his home address, 37 Lombard Street.[6] In 1806[7] he formed a business partnership with a friend and fellow ex-resident of Coldstream, James Bowman: Galloway wrote to him offering a joint business venture in return for a £200 injection of capital. Bowman moved from London, where he had gone to seek his fortune, and took up residence at Trumpet Street, Manchester.[6][8] It would appear that the partnership with Bowman coincided with a move to premises at the Caledonia Foundry at 44, Great Bridgewater Street, on the corner of Albion Street in the Gaythorn district.[7][9] At this time the business traded as millwrights but by 1813 "engineers" had been added to the description, and by 1817 there was the addition of "ironfounders".[6] The term "engineer" in relation to mechanical work was a relatively new one.[10]

Around 1820, William Glasgow, a foundryman from the Tweed who had been working in Bolton for Rothwell and Hick, joined Galloway and Bowman as a junior partner. His role was to supervise the new ironfounding section of the business. The works were extended by the purchase of additional land.[6][11] The partnership manufactured water wheels, their associated gearing, and other machinery associated with all forms of milling. As early as 1820 the men had completed some projects for customers in France (at Lille) and the United States (Charleston, South Carolina).[12]

His son, John, wrote later that

It was rather remarkable that nearly all the original millwrights in Manchester came from the neighbourhood of the Tweed ... All were Scotchmen – quiet, respectable and mostly middle aged, with experience, for in those days a man was not put to mind one machine year after year. He had to understand pretty nearly the whole process, from taking particulars and making patterns, to fixing machinery in the mill.[6]

At some time before 1828 Galloway and Bowman formed a partnership as machine makers. This was separate and in addition to their partnership with Glasgow, which continued to trade as millwrights, founders and engineers.[12] It has been speculated that Bowman married a sister of Galloway.[8]

The firm of Galloway, Bowman and Glasgow became the repair facility for the fledgling Liverpool and Manchester Railway which had no workshops of its own.[13] In 1830–31 the partnership constructed its first steam locomotive, the Manchester and by the following year had produced the Caledonian. They had wooden wheels on to which were shrunk welded metal tyres. The wheels were built by John Ashbury, who was later to become a notable engineer in his own right and the owner of the eponymous railway wagon works at Openshaw.[7][14]

Neither locomotive was initially a success, although the design problems were resolved. In the case of Caledonian the vertical cylinders were placed between the frames in front of the smokebox and drove vertically mounted connecting rods attached to the leading wheels, which were also in front of the smokebox. It had a tendency to derail and had to be rebuilt with inside cylinders and a cranked axle.[15] Vertical cylinders were the norm at this time (other builders used them too), the theory being that a horizontal or inclined arrangement would lead to premature wear due to the weight of the piston.[16] Four or five locomotives were built at a price fixed by the railway company of between £900 and £1000 each. John Galloway junior commented late in life that:

"... the trade did not seem likely to be remunerative, and we certainly did not foresee the immense possibilities of the railroad. It was generally considered that about 20 engines would be all that would be required, and competition was keenly felt at the beginning."[17]

The success to come with stationary steam engines was in no small part based on the experiences with the short-lived railway locomotive production: the locomotives had boilers rated for 50 pounds per square inch (3.4 bar), compared to the normal stationary engine boiler rating at that time of 5 or 10 psi (0.34 or 0.69 bar).[18] To put this into context, however, John Galloway senior is reported to have said that the challenges of building a locomotive were nothing compared to those of getting it out of the works and onto the railway afterwards.[19] He elaborated that

When we had constructed the engine ... we were met with the serious difficulty of getting it down to the station. We could not put steam on, nor was there a wagon which would take it; so we had to 'bar' it down to Ordsal-lane, which took a gang of men with crowbars from six o'clock in the evening until nine o'clock the next morning.[7]

By this time the partnership were producing a wide range of engineered items, including: wagons and associated parts for collieries and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway; machinery for silk mills and for salt works; steam engines for cotton mills; pipes for Benjamin Joule's[20] Salford Brewery in New Bailey Street, Salford; and also a lead rolling mill.[21]

William Galloway junior was born in 1796[3] and on 14 February 1804 his brother, John, was born at his father's Lombard Street address.[12] The brothers were both apprenticed for seven years to their father from the age of 14, William as an ironfounder and John as a millwright and engineer. Bowman's son, William, was similarly apprenticed as a millwright from 1821.[22] In the last year of his apprenticeship, 1824, John Galloway went to Dunkirk to install engines, boilers and pumps for the French government.[7]

William Galloway senior died on 7 September 1836 and some time between April and December 1838 James Bowman also died. Glasgow had given Bowman six months' notice of his wish to terminate the partnership on 11 April 1838.[23] In 1839 the Galloway brothers bought some of the stock of the erstwhile partnership which was being disposed of by auction.[17] The Caledonia foundry building was subsumed by Central Station by the 1890s.[6]

It is possible that William Glasgow was still conducting business as an ironfounder in 1841 from an address at Gloucester Street.[17]

W & J Galloway

[edit]

The Galloway brothers worked for their father's partnership until in 1835, not long before its demise they set up business together as W. and J. Galloway. They had been considering such a move since at least 1830, with John saying many years later that "there were too many in partnership already, and conflicting interests began to present themselves".[24]

The brothers built a foundry at Knott Mill, near Chester Road in Hulme on the site of former premises which had served a similar purpose but had fallen into disuse subsequent to the death of its owner, Alexander Brodie, in 1811. The site was near to William's address as known in 1832, which was 26 Jackson's Lane, Hulme. (The lane was subsequently renamed Great Jackson Street).[21][25] A key advantage of the site was the adjacent River Medlock, sources of water being vital for iron founding and the operation of steam engines, and it was the erosion caused by this watercourse which required the works to be built on two levels.[26] It has been noted that the Medlock had a greater concentration of steam engines along its length than any other similar river in England and the quality of the water was so poor, due to industrial pollution, that there were immense difficulties with priming in steam engine boilers.[27]

Before 1840 the firm had manufactured at least two steam engines, the first for Hayward of Yeovil, Somerset and the second for a mill in Glossop, Derbyshire. In that year they were successful in gaining much work in the manufacture of gas pipes and equipment for gasworks, a new and burgeoning industry. From 1842 until June 1847 the brothers were in partnership, as Galloways & Company, with Joseph Haley, in Manchester and Paris, as "Manufacturers of Patent Screw or Lifting Jacks, and as Patentees of Machines for cutting, punching and compressing Metals, and of the Rivets and other articles constructed by the said last-mentioned Machines ... [and] as Cotton Banding Manufacturers". In that month the partnership was dissolved and the Galloways continued to manufacture the machines and rivets in Manchester and Haley continued with the rivets in Paris. By 1856 they had six of these machines in their factory and manufactured two tons of rivets per machine per day, the devices being operated by one man and 20 boys.[28][29] An example of a wooden-bodied Galloway-Haley lifting jack is in Museo del Ferrocarril (railway museum) in Madrid. The patents were Haley's; for example, patent number 8768 of 31 December 1840 for an improved lifting jack and compressor.[25]

From 1848 the brothers took out numerous patents related to steam power, with John Galloway taking a particular interest in issues to improve the efficiency of boilers. Before that they had registered at least one design to improve efficiency under the Designs Act of 1843.[30] The most significant of the early patents was that of 11 March 1851 (England and Wales) and 14 April 1851 (Scotland) for the Galloway boiler, (UK patent 13532/1851, extended in 1865 for a further five years[31]). They had built boilers of this type before the patent was granted, since at least 1849, and one was exhibited in 1851 at the Great Exhibition before being purchased[32] by the West Ham Gutta Percha Company. The firm built approximately 9,000 of the type by 1891 and licensed the design for manufacture by other parties. So much work was created by this aspect of the business that in 1872 premises were obtained on Hyde Road, near Ardwick railway station,[33] to handle it, leaving the Knott Mill works to concentrate on building engines.[34]

The Lancashire boiler, which formed the basis on which the Galloways developed their 1851 design, had been patented by Sir William Fairbairn and John Hetherington in 1844.[34] In 1854 Fairbairn was sent a warning letter by the firm regarding what they believed to be an infringement of their patents. Nine years previously the Galloways had done the same to James Lillie, a former business partner of Fairbairn, with reference to a boiler-related design that they alleged had been registered by them in 1845, although there is no record of any such designs or patents of the type which were registered by the Galloways between 1843 and 1845.[30][35]

The Galloway boiler was not entirely the work of the brothers as they sought the advice of Robert Armstrong, a consulting engineer, in 1850 and it was he who arranged for the boiler to be exhibited in 1851.[36] Similarly, Sekon notes that at least one Galloway patent relating to boilers was originally devised by another person: Timothy Hackworth's 1830 design for the boiler of his locomotive The Globe was later patented by the Galloways for use with stationary steam engines.[37]

Working with Bessemer

[edit]From 1855 the firm was working with Henry Bessemer, inventor of the eponymous process, in steel manufacture; he described William Galloway as "my old friend" when writing in 1905.[38] He had been a customer of the firm since 1843 when he had developed a process for refining sugar and employed the Galloways to construct it. Bessemer and Galloways conducted a series of experiments throughout 1855 on land bought for the purpose at the Knott Mill Ironworks. This was while he was trying to prove his method, and Galloways are thought likely to have constructed the equipment that Bessemer used in his later trials at Baxter House in London, after which he announced the process to the world in August 1856 at Cheltenham. From these events comes the claim, frequently made including by John Galloway, that the first ingots of Bessemer steel were made at the Knott Mill Ironworks. Furthermore, the Galloways were the first to license Bessemer's process, obtaining the rights to operate it in Manchester and for a radius of 10 miles (16 km) around before the process was made public.[3][39][40][41] Within a month of his announcement Bessemer had raised £27,000, granting further licenses to the Dowlais Ironworks in South Wales, Govan Iron Works (Glasgow), Butterley Iron Company (Derbyshire), and a tin-plate company in Wales.[42]

The Knott Mill works were one of those at which Bessemer set up his experimental "converting vessels" when attempting to prove his process commercially late in 1856. The other test sites were Dowlais, Butterley and Govan. The tests failed to work as intended: it later became clear that this was because the pig iron used contained phosphorus whereas that with which he had experimented in London did not. The product was "rotten hot and rotten cold", according to his friend, William Clay[43] He refunded the licensees' money and an additional £5,500.[44][45] The problem was that to remove phosphorus, a basic slag was needed, but Bessemer's sand-based refractory lining (now called acidic) reacts with it into silicates rather than the phosphorus. It would take until 1877 for a basic lining to be developed, when the converter became economical to use with phosphorus-rich iron ores.

It was a further two years before Bessemer resolved the technical metallurgical problems, at which point the Galloway ironworks were once again his test site. There he trialled the steel he had produced at his London factory, which he granulated and then transported for remelting and conversion into ingots at Sheffield:[45]

So identical in all essential qualities was this steel with that usually employed that, during two months' trial of it, the workmen had not the slightest idea or suspicion that they were using steel made by a new process. They were accustomed to use steel of the best quality, costing £60 per ton, and they had no doubt whatever that they were still doing so.[46]

When this success was achieved in 1858 the Galloways gave up their licensed rights, which had not been bought back as had those of the other licensees. They went instead into partnership with Bessemer, Robert Longsdon and William Daniel Allen (long-term business partners, and both of them his brothers-in-law)[47] in building and operating his steel works in Sheffield.[39] The business, established in 1859,[3] was called Henry Bessemer & Co. and the capital input totalled around £12,000 with Bessemer and Longdon contributing £6,000, Allen contributing £500 and the Galloways £5,000. The partnership agreement was to be operational for 14 years.[39][45] It initially produced steel at £10 to £15 cheaper per ton than had previously been possible, and later for around £45 less.[48][49] The Galloways supplied equipment for its works – including tyre mills for the production of railway wheels[50] – as well as, later, for other works which licensed the process, such as the Weardale Iron Company and John Brown of Sheffield.[49] The venture blossomed, although Bessemer made more money from his licensing deals. He quotes the following profit/(loss) figures for the early years of the factory's trading:

| 1858 | 1859 | 1860 | 1861 | 1862 | 1863 | 1864 | 1865 | 1866 | 1867 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (729) | (1,093) | 923 | 1,475 | 3,685 | 10.968 | 11,827 | 3,949 | 18,076 | 28,622 |

Another involvement was in Bessemer's disastrous attempts to produce a ship with a stabilised passenger area, the SS Bessemer, for which Galloways supplied the hydraulic equipment. The concept had been that a saloon within the vessel would be supported in such a way as not to pitch, roll or yaw as the ship sailed.[52] (The ship's manoeuvrability was poor and, having crashed on its maiden voyage, investors lost confidence and the project was abandoned with the equipment remaining untested.)

The firm manufactured on behalf of Bessemer the converters for the works of the Pennsylvania Steel Company in the late 1860s.[53] Along with Hick, Hargreaves of Bolton, Galloways were the only business allowed to produce equipment for the new process.[54]

Nor might these have been their only involvement: William Galloway owned land at Runcorn and there were discussions between him and Bessemer regarding a partnership to erect a blast furnace for the purpose of manufacturing "rich manganesian pig-iron", which was required at that time to de-oxidise the molten blown metal. However, delays in progressing this idea, due to Bessemer's process gaining widespread use, ultimately resulted in Galloway feeling he was too old to embark on the venture.[55][56]

The partnership of Henry Bessemer & Co. was formally ended on 25 June 1877 "by the effluxion of time", although the Sheffield factory continued production with Allen buying Bessemer's interest in it that year. The dissolution of the partnership involved selling the business, its premises and its equipment. Including the distributions of profits made during its lifespan, each partner had at the date of effective dissolution in 1873 made 81 times the amount of money that they had original subscribed.[39] William Galloway had died in 1873[3] (his executors being John Galloway junior, John Brown Payne and John Galloway Meller), as had Robert Longsdon, whose executors were also named in the notice of partnership dissolution; Bessemer had retired from day-to-day business in the same year.[45][57] A person with the last name of Meller, but not John Galloway Meller, had been an executor to the estate of William Galloway senior.[23]

W & J Galloway & Sons

[edit]

In 1856 the sons of the firm's founders joined the partnership: John Galloway, the son of William, born on 18 July 1826 at Great Jackson Street, Manchester, and Charles John the son of John, born 25 April 1833. Both had been apprenticed to the firm and its name was adjusted to reflect their involvement.[3][49][58] Great Jackson Street was very close to the Knott Mill works and Pigot and Slater's General and Classified Directory of Manchester and Salford for 1841 not merely lists William junior living at number 69 but also John at number 55 and a Mrs Mary Galloway at 67. It also shows members of the Glasgow family, including William at 34 Great Bridgewater Street and John at 53 Great Jackson Street.[59]

Despite the expansion of the partnership a deed registered in the Court of Bankruptcy in July 1864 only names William and John Galloway, who were to receive a payment of 6s. 8d. in the pound from Thomas Redhead of Belvoir Terrace, Old Chester Road, Tranmere, the proprietor of a steam tug.[60] A petition for the winding-up of the Globe New Patent Iron and Steel Co, Ltd. in 1875 shows that by that date the partnership comprised John Galloway snr, John Galloway Jnr, Charles John Galloway and Edward Napier Galloway.[61] Edward was another son of John senior, who married a Miss Lewis in 1827 and they had four sons and a daughter.[7]

During the 1850s and 1860s the firm generated many overseas sales to countries such as Turkey, India and Russia, and for items as diverse as gunpowder mills, boilers, presses, and steam engines for use in a wide variety of applications. The firm supplied cast iron columns for buildings, constructed the pier at Southport (and then extended it, for which the tender was £3,000)[62] and, between 1855 and 1857, a 1,535 feet (468 m) railway viaduct over the River Leven close to Ulverston. The pier and the bridge employed a new construction method devised by John Galloway, using pressurised water jets to create the holes into which the piles were later driven.[41][63]

Galloways were among the well-known promoters of a new business, The Lancashire Steel Company Ltd., in 1863. The intention was that this company would develop a 10 acre site at Gorton with buildings, blast furnaces and all the necessaries of steel production by the Bessemer process, in order initially to produce 200 tons a week of steel in blocks weighing up to 10 tons. The site was adjacent to the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, for ease of transport. It was planned to eventually produce 20 ton blocks and to equip it with the most powerful tooling so that the company could supply the maritime market. Capitalisation was to be £150,000.[64] In fact, the venture was a failure and it was wound-up in 1867.[65]

Around 1873 the firm supplied two blowing engines to the huge Krupp steelworks at Essen, Germany.[66] It was in this decade that the company began to install flat belt drive systems for the transfer of power from its stationary steam engines to the looms and similar machinery which they were intended to service. This technique was common in the US but rare in Britain until this time: the advantages included less noise and less wasted energy in the friction losses inherent in the previously common drive shafts and their associated gearing. Also, maintenance was simpler and cheaper, and it was a more convenient method for the arrangement of power drives such that if one part were to fail then it would not cause loss of power to all sections of a factory or mill. These systems were in turn superseded in popularity by rope drive methods.[67]

Charles John Galloway had a particular interest in exhibitions. The firm displayed two 40 horsepower Galloway boilers at the 1873 Vienna Universal Exhibition, and a 35 horsepower compound engine.[68] In 1876 the firm was gazetted for an award for Services to the American Executive in Machinery Department at the Philadelphia International Exhibition,[69] and he was awarded the title of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour after the Paris Exhibition of 1878, raised to the rank of Officer after the similarly titled event of 1889. He was very active in the organisation of the Royal Manchester Jubilee Exhibition of 1887.[58] John Galloway junior was chairman of the organising committee for the latter event.[11] Some years later, in 1894, Galloways won the Grand Prix in the Motive & Machines section of the Antwerp International Exhibition.[70]

Charles John did not limit his activities to that of the family firm and was chairman of Boiler Insurance and Steam Power Co. Ltd. in September 1880, when an extraordinary general meeting held in King Street, Manchester resolved to liquidate the company and sell its business and assets.[71] He was also a director of the Manchester Ship Canal Company[72] and had been a director of the Steam Boiler Assurance Co. Ltd.[73]

Galloways Ltd.

[edit]The partnership was converted into a private company, Galloways Ltd., in 1889, with a share capital of £250,000 in £100 shares. The initial subscribers, who each took one share, were John Galloway, John Galloway junior, Charles John Galloway, Edward Napier Galloway, Arthur Walter Galloway, John Henry Beckwith, W E Norbury and C Rought – all but the last giving their address as the Knott Mill Ironworks.[74] Beckwith, MIMechE, had been a frequent co-applicant with Charles John Galloway in applications for patents and provisional protection thereof: he had joined the company in his early 20s in 1864 as a draughtsman and, after a brief interlude working for another business in Buenos Aires, returned in 1867; by 1877 he was chief design engineer and he became managing director with the conversion to limited company status; he resigned as managing director in 1897 but kept his seat on the board of directors until his death one year later.[75]

John Galloway junior had been increasingly involved in the management of the partnership as it grew rapidly but the restructuring of the partnership as a company saw Charles John Galloway installed as chairman and managing director.[3] John Galloway junior had numerous other business interests, and was a JP (as was Charles) and had a great interest in philanthropy. His business interests included being chairman of Earle's Shipbuilding and Engineering Company at Hull, and a director of Carnforth Hematite Iron Co, (correct spelling, founded 1865[76]) the North of England Trustee, Debenture & Assets Corporation Ltd., Hoyland & Silkstone Colliery Co. and the Blackpool Land Company.[11] Earle's had built the SS Bessemer.

Five years later, on 11 February 1894, John Galloway senior died aged almost 90. His estate was valued at £143,117[3] and by this time the company had 500 employees at the Knott Mill site and a further 800 at Ardwick.[34] His last home address was Coldstream House, Old Trafford and his executors were William Lewis Galloway (a sugar refiner, of The Lawn, Brook Lane, Timperley and sometime councillor of the County Borough of Salford),[77] Edward Napier Galloway (Normanby, Altrincham) and John Galloway Meller (a land agent of Cooper Street, Manchester).[78] An engineer, Edward Galloway was appointed a Land Tax Commissioner in 1899;[79] he died on 5 October 1919 when living at Hill Rise, Leicester Road, Altrincham.[80] The children of John Galloway established a charitable fund in memory of him and his wife, Emma, in 1895.[81] This survived under the name of the John and Emma Galloway Memorial until October 1991, when it was amalgamated.[82]

John Galloway junior died on 16 December 1896 at his home, The Cottage, Seymour Grove, Manchester. He left one son, William Johnson Galloway, born in 1868, who was also involved with the family firm and was at the time of his father's death the Conservative MP for Manchester South-west (his father, although keeping a low profile, was of Liberal persuasion and a member of the United Presbyterian Church).[3] Both of these men were interred at Weaste Cemetery, Salford.[11]

There was a capital restructuring in 1895,[83] and in 1899 the business became a public limited company.[49][84] Somewhere between these dates the chairmanship appears to have moved from Charles John Galloway to Edward Napier Galloway, according to the announcements in The London Gazette. However, The Engineer reported Charles John as chairman at the company's annual general meeting in 1901 and noted that Sir Richard Mottram was a director.[85] Mottram was Mayor of Salford between 1894 and 1898; he held other directorships with Manchester Liners Ltd (or perhaps Manchester Linen Ltd)[86] and Chillan Mills Co Ltd.[87]

The 1901 meeting authorised a dividend payment of 6% and the issue of 2,746 shares at £10 each in order to aid investment in plant and extended premises for the purpose of manufacturing 'high-speed engines'. This issue of shares amounted to 20% of the then issued capital, and they were taken up by existing shareholders.[85] In the same year the company considerably extended its Knott Mill factory, at which time a visitor noted in particular the work in progress on "several exceptionally large engines for iron and steel works" (one had a 45 ton, 24-foot diameter flywheel and a total weight of 230 tons) and also a wood treatment plant for the Northern Wood Haskinising Company (haskinising was a wood preservation technique[88]).[89] There were reports at this time that the company had licensed and was developing Pictet's discovery of an improved method for the production of oxygen gas, although there were suggestions that this may have been as part of a syndicate involving other Manchester businesses. The plan was for Pictet to experiment further at the Galloway works and if the outcome was successful then a new company would be formed.[90]

The 1902 annual general meeting confirmed that the expansion was complete, voted a similar dividend and re-elected William Johnson Galloway and Charles Rought as directors; it also noted that an order for a blowing machine from Carnforth Hematite was being processed.[91]

Charles John Galloway died on 14 March 1904. His address at the time of death was Thorneyholme, Knutsford and his executors were Arthur Walter Galloway, Henry Bessemer Galloway and William Sharp Galloway, his sons.[92] He was interred at Mobberley Church.[58]

The Galloway boiler was still being improved around this time. In 1902 the company introduced a superheater and in 1910 began to use another design of the same.[93]

The company was involved in a significant court case in 1912, which went to the highest court of the land and was subsequently cited in other cases, including in the United States.[94] In 1902 a Mr Noden, employed as a riveter, had an accident at work which resulted in the amputation of a finger. He resumed work at the company in 1903 as a caulker, which involved using a light hammer, but in 1910 was instructed to use a heavy pneumatic hammer. The vibration from this heavier hammer caused his hand to become inflamed and he sought compensation, based on his injury of 1902. A lower court awarded him this compensation but the judgment was overturned on appeal by the Law Lords, who directed that there was no evidence that the 1902 accident was a contributory cause of his injury of 1910 and that, in any event, the latter incident was not actually an accident at all and therefore there was no entitlement to compensation under the terms of the 1897 Workmen's Compensation Act.[95]

There had been a previous judgement of some legal significance in 1900, being the matter of Statham vs Galloways Ltd. In this instance an employee had obeyed the order of a superior and as a consequence of doing so had suffered injury. The ruling was that the injured employee had stepped outside the Workmen's Compensation Act by doing something which he knew to be outside the scope of his duties but, nonetheless, obedience was also a duty and that obedience took precedence.[96][97]

The company was placed in receivership on the application of its debenture holders in 1912, despite the business being "much more promising than for some time past". The cause of this was a proposal to issue prior lien debentures to the value of £50,000, a move which would dilute the position of existing debenture holders. It was reported that the company might be restructured in order to resolve this issue.[98]

There was a restructuring of the company on 27 July 1925, a scheme of arrangement being made with shareholders and debenture holders such that the capital was reduced from £330,000 to £198,192.[100] The following year saw the company take on the drawings and patterns of John Musgrave & Sons following the closure of that business.[101]

It has been calculated that the number of engineering firms in Manchester more than halved between 1899 and 1939, with the inter-war recession causing particularly severe contraction in the manufacturing spheres of textile machinery, locomotive engineering and boilermaking. The businesses most likely to survive were those that did not rely extensively on exports, on the production of capital goods and on time-served skilled labour – "the newer, more capital-intensive, mass-production, domestic market-oriented engineering firms, employing a large proportion of semi-skilled labour fared better and dominated the industry by 1939."[102]

The company went into receivership in 1932[103] and in 1933, Hick, Hargreaves & Co. purchased the complete records, drawings and patterns of the defunct W & J Galloway Limited.[104]

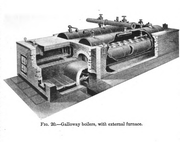

Galloway boiler and Galloway tubes

[edit]In 1848, Galloways patented the Galloway tube, a tapered thermic syphon water-tube inserted in the furnace of a Lancashire boiler.[105] The tubes are tapered, simply to make their installation through the flue easier.[106]

These were followed in 1851 by the Galloway boiler.[107][108] The flues beyond the two furnaces of the Lancashire boiler were merged into a single wide flue.[109] This widened and flat-topped flue was stayed by the use of many conical vertical Galloway tubes being riveted into it, improving the circulation of water and increasing the heating surface.

Patent applications involving family

[edit]| App. No. | App. Date | For | First Named | Second Named | Voided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 208[110] | 27 January 1853 | improvements in steam engines and boilers | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[111] |

| 570[112] | 14 March 1855 | certain improvements in balancing or regulating the pressure on the slide-valves of steam-engines | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £100 within 7 years[113] |

| 1132[114] | 14 May 1856 | improvements in machinery for rasping, cutting and chipping dye woods | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[115] |

| 1217[116] | 22 May 1856 | improvements in steam boilers | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[117] |

| 3083[118] | 15 December 1857 | improvements in hydraulic presses | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[119] |

| 801[120] | 14 April 1858 | improvements in apparatus and furnaces for heating, welding, or melting metals, parts of which improvements are applicable to other furnaces | Robert Armstrong | John Galloway | |

| 1407[121] | 22 June 1858 | improvements in machinery for cutting, bruising, chipping, and rasping, and otherwise treating or preparing dye woods and roots, or other vegetable substances | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[122] |

| 2960[123] | 3 December 1860 | improvements in steam boilers | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £100 within 7 years[124] |

| 521[125] | 1 March 1861 | improvements in moulding wheels and other metal articles | William Galloway | John Galloway | |

| 1948[126][127] | 6 August 1861 | improvements in steam boilers and apparatus connected therewith | William Galloway | John Galloway & John William Wilson | Failure to pay £100 within 7 years[128] |

| 3043[129] | 12 November 1862 | improvements in machinery or apparatus for cutting, shaping, punching, and compressing metals | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £100 within 7 years[130] |

| 2066[131] | 20 August 1863 | improvements in steam boilers and in steam and water gauges (sic) for the same | William Galloway | John Galloway | |

| 2343[132] | 23 September 1863 | improvements in lubricating journals of revolving shafts and axles, and in the apparatus employed for that purpose | William Galloway | John Galloway | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[133] |

| 3110[134] | 10 December 1863 | improvements in presses for the bending of metal plates into the various forms required in naval architecture, and for other purposes | William Galloway | John Galloway* | |

| 1937[135] | 3 July 1867 | improvements in the manufacture of welded tubes and in the apparatus employed for that purpose, which latter are partly applicable to other purposes | William Galloway | George Plant | |

| 2815[136] | 7 October 1867 | improvements in looms for weaving | Charles John Galloway | ||

| 591[137] | 22 February 1868 | improvements in wrought iron and stei.'l pilus[sic], pillars, and columns | Charles John Galloway | ||

| 2221[138] | 14 July 1868 | improvements in operating piston valves of steam engines | Charles John Galloway | Charles Herbert Holt | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[139] |

| 2253[140] | 17 July 1868 | improvements in boilers for generating steam and in apparatus connected therewith for heating the feed water | Charles John Galloway | Charles Herbert Holt | Failure to pay £100 within 7 years[141] |

| 1385[142] | 5 May 1869 | improvements in slide valves and valve gear to piston valves for steam engines | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | Failure to pay £50 within 3 years[143] |

| 247[144] | 30 January 1871 | improvements in valves blowing engines, also applicable to air and other pumps | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | Failure to pay £100 within 7 years[145] |

| 1620[146] | 5 May 1873 | improvements in the slide valves of compound steam engines | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | |

| 4036[147] | 8 December 1873 | improvements in steam boilers | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | |

| 2514[148] | 13 July 1875 | improvements in steam boilers | Charles John Galloway | Charles Herbert Holt | Probably US 180863 |

| 2881[149] | 14 August 1875 | improvements to the apparatus for the manufacture and fixing of taper and flanged tubes for boilers | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | |

| 158[150] | 14 January 1876 | improvements in steam boilers | Charles John Galloway | US 253365 | |

| 2439[151] | 13 June 1876 | improvements in the valve gear of steam and other engines | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | |

| 3371[152] | 5 September 1877 | improvements in boiler flues | Charles John Galloway | ||

| 4617[153] | 6 December 1877 | improvements in pumps for raising or forcing liquids | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | |

| 2410[154] | 18 June 1878 | improvements in apparatus for rivetting the flanges of boiler tubes | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | |

| 27 May 1879 | friction-clutch | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | US 226302 | |

| 7929 | 22 May 1890 | water-tube boiler | Charles John Galloway | John Henry Beckwith | US 442036 |

| GB 189413362 | 10 July 1894 | improvements in Galloway boilers | Charles John Galloway | US 537763 | |

| GB 189517425 | 18 September 1895 | improvements in boiler furnaces | Galloways Ltd | Henry Foster | |

| GB 189517500 | 19 September 1895 | improvements in Corliss valve gear for steam engines | Galloways Ltd | John Henry Beckwith | |

| GB 189628492 | 12 December 1896 | improvements in apparatus for drilling and rivetting the tube flanges and flue plates of Galloway boilers | Galloways Ltd | John Henry Beckwith | |

| GB 189629086 | 18 December 1896 | an improvement in shut-off valves | Galloways Ltd | John Henry Beckwith | |

| GB 189807005 | 22 March 1898 | improvements in compound steam or other fluid pressure engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Foster, Alfred Etchells | |

| GB 189820284 | 24 September 1898 | an improvement in gear for working Corliss and such like valves | Galloways Ltd | Alfred Etchells | |

| GB 189821414 | 11 October 1898 | an improvement in multiple flue boilers | Galloways Ltd | William Bayliss | |

| GB 190017470 | 2 October 1900 | improvements in compound safety and low water valves | Galloways Ltd | William Bayliss | |

| GB 190017469 | 2 October 1900 | an improvement in valve apparatus for reversing rolling mill and similar engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Foster | |

| GB 190107698 | 15 April 1901 | an improvement in centrifugal and inertia governors | Galloways Ltd | Herbert Lindley | |

| GB 190328035 | 21 December 1903 | improvements in steam generators | Galloways Ltd | William Bayliss | |

| GB 190328034 | 21 December 1903 | improvements in and relating to steam superheaters | Galloways Ltd | William Bayliss | |

| GB 191004774 | 25 February 1910 | an improved cross-box for connecting the headers of a water tube boiler with the main steam and water drum | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 191009286 | 16 April 1910 | improvements in steam engine valve chambers | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 191019348 | 17 August 1910 | improvements in steam superheaters | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 191102613 | 1 February 1911 | improvements in controlling gear for steam driven rolling mill engines, winding engines and the like | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 191107296 | 23 March 1911 | improvements in covers for vessels containing fluid under pressure | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 191409971 | 22 April 1914 | improvements in reciprocating piston engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | Failed to pay, voided 22 April 1923;[155] reapplied November 1924, successful 12 February 1925[156] |

| GB 103531 | 2 January 1916 | improvements in valve gear for reciprocating steam engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 118462 | 9 December 1916 | improvements in cylinders for uniflow steam engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 116799 | 30 July 1917 | improvements relating to cylinders of uniflow steam engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 114094 | 14 September 1917 | an improved automatic valve | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| 27 September 1917 | improvements in and relating to valves for engines | Henry Crowe | Assigned to Galloways US 1367357 | ||

| GB 123147 | 11 February 1918 | improved means for connecting the piston to the piston rod of a motive fluid engine | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 127797 | 6 March 1919 | an improved piston for gas engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 128879 | 7 March 1919 | improvements relating to exhaust valve boxes of internal combustion engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 142692 | 12 June 1919 | improvements relating to superheaters | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 152863 | 19 October 1919 | improvements in or relating to the operation of valves by fluid pressure | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 151198 | 28 January 1920 | improvements relating to pistons of uniflow steam engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 162913 | 1 May 1920 | improvements relating to water tube boilers | Galloways Ltd | Ralph John Smith | |

| GB 182159 | 28 February 1921 | improvements in reciprocating piston engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 184101 | 24 October 1921 | improvements in steam superheaters | Galloways Ltd | Harold Ashton | |

| GB 229170 | 23 June 1924 | improvements in balanced valves for steam or other elastic fluid engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 235734 | 19 July 1924 | improvements relating to steam generators | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 233566 | 21 July 1924 | improvements in apparatus for accumulating the heat of exhaust steam and for heating water | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 232131 | 7 November 1924 | improvements relating to the valve gear of steam engines | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 251844 | 24 September 1925 | improvements relating to pressure regulators | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 277843 | 28 December 1926 | improvements relating to tubular structures such as superheaters, water heaters, airheaters and the like | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 276215 | 28 December 1926 | improvements relating to boilers, superheaters, feed water heaters and the like | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling | |

| GB 312815 | 7 June 1928 | improvements relating to tubular structures such as superheaters, water heaters, airheaters and the like | Galloways Ltd | Henry Pilling, Albert Edward Leek | Addition to 277843 |

See also

[edit]- Manchester Hydraulic Power, an example of Galloways' steam-powered hydraulics work

- William Johnson Galloway (1868–1931), only son of John Galloway junior, was recorded as a director of the company at various dates from 1892[157] to 1905.[158] His directorship may have extended before and after these years.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Carter, Edward Tremlett (1896). Motive power and gearing for electrical machinery: a treatise on the theory and practice of the mechanical equipment of power stations for electric supply and for electric traction. "The Electrician" series. New York: D. Van Nostrand Co. pp. 323, 560. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Selfe, Norman (1900). Machinery for refrigeration. Chicago: H. S. Rich & Co. p. 216. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i ODNB

- ^ Chaloner p. 99.

- ^ Musson, A. E.; Robinson, E. (June 1960). "The Origins of Engineering in Lancashire". The Journal of Economic History. 20 (2). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association: 223. doi:10.1017/S0022050700110435. JSTOR 2114855. S2CID 154008652.

- ^ a b c d e f Chaloner p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f "John Galloway". The Engineer. 16 February 1894.

- ^ a b Chaloner p. 118.

- ^ "The Boulton & Watt Archive and the Matthew Boulton Papers from Birmingham Central Library" (PDF). Adam Matthew Publications. 12 October 1833. p. 5. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Musson, A. E.; Robinson, E. (June 1960). "The Origins of Engineering in Lancashire". The Journal of Economic History. 20 (2). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association: 215. doi:10.1017/S0022050700110435. JSTOR 2114855. S2CID 154008652.

- ^ a b c d "Obituary". Transactions of the Manchester Association of Engineers: 318–320. 1896. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Chaloner p. 101.

- ^ Rendell p. 3.

- ^ Chaloner p. 107.

- ^ Sekon, GA (1899). The Evolution of the steam locomotive, 1803–1898. London: The Railway Publishing Co Ltd. pp. 54–55. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Rendell p. 12.

- ^ a b c Chaloner p. 109.

- ^ Rendell p. 4.

- ^ Rendell p. 48.

- ^ Reynolds, Osbourne (1892). "Memoir of James Prescott Joule". Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. 4th. 6. Manchester: Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society: 25–26. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ a b Chaloner p. 108.

- ^ Chaloner p. 103.

- ^ a b "No. 19712". The London Gazette. 1 March 1839. p. 474.

- ^ Chaloner p. 104.

- ^ a b Chaloner p. 119.

- ^ Archives of Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester

- ^ Hills p. 129.

- ^ "No. 20745". The London Gazette. 18 June 1847. p. 2236.

- ^ Chaloner p. 110.

- ^ a b Chaloner p. 111.

- ^ "No. 22947". The London Gazette. 10 March 1865. p. 1448.

- ^ Armstrong, Robert (1856). The Modern Practice of Boiler Engineering. London: E & F N Spon. p. 53. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Shaw, William Arthur (1894). Manchester Old and New. London: Cassell. p. 65.

- ^ a b c Chaloner p. 112.

- ^ Chaloner p. 120.

- ^ Armstrong, Robert (1856). The Modern Practice of Boiler Engineering. London: E & F N Spon. pp. 35, 54. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Sekon, GA (1899). The Evolution of the steam locomotive, 1803–1898. London: The Railway Publishing Co Ltd. p. 47. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Bessemer p. 287.

- ^ a b c d Bessemer pp. 176–177.

- ^ Lord, W. M. (1945). "The Development of the Bessemer Process in Lancashire, 1856–1900". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 25: 166. doi:10.1179/tns.1945.017.

- ^ a b Chaloner pp. 113–116.

- ^ Bessemer pp. 167–168.

- ^ Erickson, Charlotte (1986) [1959]. British industrialists: steel and hosiery 1850–1950. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-566-05141-9.

- ^ Bessemer pp. 170–172.

- ^ a b c d Tweedale, Geoffrey (2004). "Bessemer, Sir Henry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2287. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Bessemer p. 175.

- ^ Goodale, Stephen Lincoln; Speer, J. Ramsey (1920). Chronology of iron and steel. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Iron & Steel Foundries Company. p. 142. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Bessemer p. 189.

- ^ a b c d Chaloner p. 117.

- ^ Hewitt, Abram S. (1868). The production of iron and steel. Washington, US: Government Printing Office. p. 57.

- ^ Bessemer p. 334.

- ^ Bessemer p. 325.

- ^ Bessemer p. 339.

- ^ Lord, W. M. (1945). "The Development of the Bessemer Process in Lancashire, 1856–1900". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 25: 169. doi:10.1179/tns.1945.017.

- ^ Bessemer p. 285.

- ^ Lord, W. M. (1945). "The Development of the Bessemer Process in Lancashire, 1856–1900". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 25: 171. doi:10.1179/tns.1945.017.

- ^ "No. 24480". The London Gazette. 10 July 1877. p. 4082.

- ^ a b c "Chas. John Galloway". Transactions of the Manchester Association of Engineers: xvi–xvii. 1904. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Pigot and Slater's General and Classified Directory of Manchester and Salford. Manchester: Pigot and Slater. 1841. pp. 101, 105. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ "No. 22875". The London Gazette. 15 July 1864. p. 3597.

- ^ "No. 24218". The London Gazette. 11 June 1875. p. 3063.

- ^ "Tenders". The Builder. 21 (1063): 451. 20 June 1863. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Brunlees, James (1858). Description of the iron viaducts erected across the tidal estuaries of the Rivers Leven and Kent. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ "Advertisement", The Chemical News, 7, London: J H Dutton: 63, 1 August 1863, retrieved 5 February 2011

- ^ "No. 23302". The London Gazette. 17 September 1867. p. 5133.

- ^ "Progress of the iron and steel industries: Germany". Van Nostrand's Eclectic Engineering Magazine. 11. New York: D Van Nostrand: 173. July–December 1874. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Hills (1989), pp. 208–210.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Vienna Universal Exhibition 1873 (1874). Reports on the Vienna Universal Exhibition of 1873. HMSO. pp. 203. 204. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "No. 24527". The London Gazette. 30 November 1877. p. 6897.

- ^ "No. 26579". The London Gazette. 14 December 1894. p. 7360.

- ^ "No. 24888". The London Gazette. 5 October 1880. p. 5166.

- ^ "Transactions". Manchester: The Manchester Association of Engineers. 1904: XVII. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Steam Boiler Assurance Company, Market-Street, Manchester". The Mechanics' Magazine. New series. 1 (10): iv. 4 March 1859.

- ^ "Galloways Ltd". The Chemical Trade Journal. 4. Manchester: Davis: 235. 1889. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "Memoirs". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Westminster, London: 701–702. 1898. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Lord, W. M. (1945). "The Development of the Bessemer Process in Lancashire, 1856–1900". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 25: 172. doi:10.1179/tns.1945.017.

- ^ "Municipal Elections". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 31 October 1867. p. 4. (subscription required)

- ^ "No. 26497". The London Gazette. 23 March 1894. p. 1751.

- ^ "No. 27107". The London Gazette. 11 August 1899. p. 5041.

- ^ "No. 31841". The London Gazette. 30 March 1920. p. 3956.

- ^ "Manchester: The parish and advowson". A History of the County of Lancaster. Vol. 4. 1911. pp. 192–204. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "1004692 – John and Emma Galloway Memorial". Charities Commission. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "No. 26638". The London Gazette. 28 June 1895. p. 3674.

- ^ "No. 27089". The London Gazette. 13 June 1899. p. 3747.

- ^ a b "Galloways Limited, Manchester". The Engineer. 1 March 1901.

- ^ Dod's peerage, baronetage and knightage. S. Low, Marston & Co. 1901. p. 618.

- ^ Who Was Who. Vol. 1. London: A. & C. Black. 1962. p. 510.

- ^ "Cubitt Town". British History Online. University of London & History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Notes from Lancashire". The Engineer: 359. 5 April 1901.

- ^ "A new oxygen process and the metal trade". The Age of Steel. 90 (13). St Louis, MO.: Journal of Commerce Co.: 35 28 September 1901. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "Galloways Limited, Manchester". The Engineer. 7 March 1902.

- ^ "No. 27702". The London Gazette. 5 August 1904. p. 5082.

- ^ Inchley, W. (1912). Steam boilers and boiler accessories. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 268–270. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "McDonough v. Sears, New Jersey Supreme Court 1941". Bellevue, WA: VersusLaw. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Stone, Gilbert; Groves, Keith Grimble (1914). Stone's Insurance Cases. Vol. 2. London: The Reports and Digest Syndicate. p. 832. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

1 K. B. 46; 81 L. J. K. B. 28; 105 L. T. 567; 28 T. L. R. 5; 55 S. J. 838; 5 B. W. C. C. 7; [1912] W. C. Rep. 63—C. A.

- ^ Adshead, Elliott (1903). The Workmen's Compensation Acts. Being an Annotated Study of the Workmen's Compensation Act, 1897, and the Workmen's Compensation Act, 1900. Manchester: Sherratt & Hughes. p. 18. ISBN 9780543984203.

- ^ Dresser, Frank F. (1908). The Employers' Liability Acts. Vol. 2. St Pauls, Minnesota: Keefe Davidson. p. 105.

- ^ "Manchester Boilermakers' Affairs". The Engineer. 31 May 1912.

- ^ "Elm Street Mill Cross-Compound Steam Engine". Science and Industry Museum.

- ^ "No. 33083". The London Gazette. 11 September 1925. p. 5986.

- ^ Hills (1989), p. 267.

- ^ McIvor, Arthur J. (2002). Organised capital:employers' associations and industrial relations in northern England 1880–1939. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-521-89092-2. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Henry Pilling Papers". The National Archives. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ P. W. Pilling, Hick Hargreaves and Co., The History of an Engineering Firm c. 1833–1939, a Study with Special Reference to Technological Change and Markets (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, University of Liverpool, 1985), pp. 384–444

- ^ "Lancashire Boiler" (PDF). Museum of Science & Industry, Manchester.

- ^ K. N. Harris (1974). Model Boilers and Boilermaking. MAP. ISBN 0-85242-377-2.

- ^ UK patent 13532, 1851

- ^ Hills (1989), p. 134.

- ^ "Galloway boiler inner flue" (photo). Grace's Guide.

- ^ "No. 21410". The London Gazette. 11 February 1853. p. 380.

- ^ "No. 21886". The London Gazette. 23 May 1856. p. 1869.

- ^ "No. 21686". The London Gazette. 30 March 1855. p. 1295.

- ^ "No. 22623". The London Gazette. 6 May 1862. p. 2385.

- ^ "No. 21888". The London Gazette. 30 May 1856. p. 1945.

- ^ "No. 22290". The London Gazette. 22 July 1859. p. 2859.

- ^ "No. 21890". The London Gazette. 6 June 1856. p. 2029.

- ^ "No. 22290". The London Gazette. 22 July 1859. p. 2861.

- ^ "No. 22076". The London Gazette. 25 December 1857. p. 4556.

- ^ "No. 22474". The London Gazette. 25 January 1861. p. 308.

- ^ "No. 22132". The London Gazette. 30 April 1858. p. 2098.

- ^ "No. 22158". The London Gazette. 2 July 1858. p. 3141.

- ^ "No. 22533". The London Gazette. 26 July 1861. p. 3159.

- ^ "No. 22462". The London Gazette. 21 December 1860. p. 5153.

- ^ "No. 23332". The London Gazette. 13 December 1867. p. 6833.

- ^ "No. 22490". The London Gazette. 15 March 1861. p. 1202.

- ^ "No. 22541". The London Gazette. 23 August 1861. p. 3480.

- ^ *"Abridged specifications of patents". The Mechanics' Magazine. London. 21 February 1862. p. 131. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ "No. 23412". The London Gazette. 14 August 1868. p. 4530.

- ^ "No. 22685". The London Gazette. 28 November 1862. p. 5941.

- ^ "No. 23557". The London Gazette. 19 November 1869. p. 6231.

- ^ "No. 22768". The London Gazette. 4 September 1863. p. 4331.

- ^ "No. 22776". The London Gazette. 2 October 1863. p. 4749.

- ^ "No. 23170". The London Gazette. 5 October 1866. p. 5346.

- ^ "No. 22804". The London Gazette. 8 January 1864. p. 114.

- ^ "No. 23278". The London Gazette. 19 July 1867. p. 4054.

- ^ "No. 23312". The London Gazette. 18 October 1867. p. 5567.

- ^ "No. 23359". The London Gazette. 6 March 1868. p. 1532.

- ^ "No. 23410". The London Gazette. 7 August 1868. p. 4403.

- ^ "No. 23757". The London Gazette. 21 July 1871. p. 3278.

- ^ "No. 23410". The London Gazette. 7 August 1868. p. 4404.

- ^ "No. 24230". The London Gazette. 23 July 1875. p. 3730.

- ^ "No. 23497". The London Gazette. 14 May 1869. p. 2834.

- ^ "No. 23858". The London Gazette. 17 May 1872. p. 2373.

- ^ "No. 23732". The London Gazette. 28 April 1871. p. 2086.

- ^ "No. 24550". The London Gazette. 8 February 1878. p. 649.

- ^ "No. 23976". The London Gazette. 16 May 1873. p. 2461.

- ^ "No. 24046". The London Gazette. 19 December 1873. p. 6045.

- ^ "No. 24228". The London Gazette. 16 July 1875. p. 3630.

- ^ "No. 24240". The London Gazette. 27 August 1875. p. 4298.

- ^ "No. 24305". The London Gazette. 14 March 1876. p. 1923.

- ^ "No. 24339". The London Gazette. 27 June 1876. p. 3638.

- ^ "No. 24507". The London Gazette. 28 September 1877. p. 5424.

- ^ "No. 24533". The London Gazette. 21 December 1877. p. 7362.

- ^ "No. 24606". The London Gazette. 19 July 1878. p. 4216.

- ^ "No. 32997". The London Gazette. 28 November 1924. p. 8694.

- ^ "No. 33020". The London Gazette. 13 February 1925. p. 1100.

- ^ The General Election – Biographies of Candidates, The Times, 1 July 1892, p.5

- ^ Dod's Parliamentary Companion (81st issue, 73rd year ed.). London: Whittaker. p. 252. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chaloner, W. H.; Farnie, D. A.; Henderson, W. O., eds. (1990). Industry and Innovation: Selected Essays of W.H. Chaloner. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-3335-6.

- Bessemer, Sir Henry (1905). An Autobiography. London: Engineering.

- Hills, Richard L. (1989). Power from Steam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45834-X.

- Birse, Ronald M. (2011). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: OUP. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Rendell, Samuel (1906). "The Steam Locomotive Fifty Years Ago and Now". Transactions of the Manchester Association of Engineers (January–March).

External links

[edit]- "Galloways, Ardwick" Frank Wightman (1979) Manchester Archives+

- Manchester, the World's First Industrial City

- Graces Guide 'Galloways'

- Boilers at the Papplewick Pumping Station

- Detail of 1900 Mitchell and Kenyon film of Galloways employees outside Hyde Road factory

- W & J Galloway & Sons Letter Books (typescript copies) at the John Rylands Library, Manchester.