Funeral procession

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2010) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Dutch. (August 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

A funeral procession is a procession, usually in motor vehicles or by foot, from a funeral home or place of worship to the cemetery or crematorium.[1][2] In earlier times the deceased was typically carried by male family members on a bier or in a coffin to the final resting place.[3] This practice has shifted over time toward transporting the deceased in a hearse, while family and friends follow in their vehicles.[1] The transition from the procession by foot to procession by car can be attributed to two main factors; the switch to burying or cremating the body at locations far from the funeral site and the introduction of motorized vehicles and public transportation making processions by foot through the street no longer practical.[1][4]

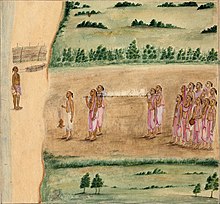

Hinduism

[edit]

The Indian city of Banāras is knowns as the Great Cremation Ground because it contains Manikarnikā, the location where Hindu's bring the deceased for cremation. Manikarnikā is located in the center of the city along the Ganges River.[5] The funeral procession normally takes place from the house of the deceased to the cremation ground and is normally an all-male affair.[6] The eldest son leads the procession followed by others.[7] Contrary to western traditions, the procession leaves as soon as possible after death and mourners chant the name of god en route to the crematorium.[8][9] The body itself is bathed and wrapped in a white sheet, carried to the cremation ground on a bamboo litter.[3] The son leading the procession carries a fire pot when he leaves the house, which is used to light the funeral pyre.[7][3] The procession ends at Manikarnikā, where the body is dipped in the Ganges River, then sprinkled with sandalwood oil and covered with garlands of flowers before being cremated.[5]

In more modern times and places outside of India, the domestic traditions of decorating the body, circumambulating, and offering rice balls occurs at the family home or funeral home instead of at the cremation site.[2] No large procession takes place, but rather the male family members carry the coffin from the home to the hearse and then follow in cars to the crematorium. The coffin is again carried by the men from the hearse into the chapel at the crematorium.[2] The chief mourner and male family members will flip the switch to light the cremator after the funeral ceremony takes place. In some cases, the family will travel farther to spread the ashes of the deceased in a holy river. However, if they choose not to do so, the ashes will be spread in the sea or a river nearby.[2]

Islam

[edit]In the Islam religion, the funeral procession is a virtuous act that typically involves a large amount of participation from other Muslims. Traditions that were begun by the Prophet are what urged Muslims to partake in the procession. Muslims believe that by following the funeral procession, praying over the body, and attending the burial one may receive quīrāts (rewards) to put them in good favor with Allah.[10] Funeral processions of prominent figures in the Islamic society would attract large crowds because many people would want to honor the deceased. The number of people attending one's funeral can be considered a mark of social standing being that the more well-known and influential one was, the more likely people were to attend. In some cases, the governor may insist on leading the funeral procession for men of high prominence even if this is against the wishes of the family of the deceased.[10] Muslim funeral processions may also attract people of other religions at times if the deceased is well known in society. However, Muslims will always be the ones carrying the body on a bedstead, while other religions may follow alongside, typically staying in their own groups. Islamic funeral processions have been viewed as similar to those in late antiquity Alexandria, being that the whole city would partake in the procession and lights and incense would be used as well.[10]

Christianity

[edit]

In the Christian religion, the funeral procession was originally from the home of the deceased to the church because this was the only procession associated with burial. This is because the burial took place on the church property so there was no procession that occurred after the funeral service.[1] Later on, as the deceased began to be buried in cemeteries that were not at the church, the main funeral procession was considered to be from the church to the place of burial. This switch was mainly due to the monastic influence over time.[1] When the place of burial was at the church or nearby, the body was carried to the grave/tomb. Those carrying the coffin were led by others carrying wax candles and incense. The incense signify a sign of honor for the deceased.[1] Psalms and antiphons were also sung along the way. One antiphon that has been used in funeral processions for a very long time is called In Paradisum:

May the angels lead you into paradise

may the martyrs come to welcome you

and take you to the holy city,

the new and eternal Jerusalem.[1]

In the modern day, the funeral procession is no longer common or practiced in the same way. Now a hearse is used to transport the body to the gravesite. The procession consists of carrying the casket from the church to the hearse and then from the hearse to the gravesite once at the cemetery. The male family members and friends are typically the ones who carry the coffin.[1]

Buddhism/Shinto (Japan)

[edit]

After a person has died the first thing to be done is to choose two people to be in charge of making all of the arrangements for the funeral events to come. The main relatives are in charge of encoffining the body and the female relatives make the death clothes that the deceased will wear. Once the body is prepared the wake occurs. This takes place the night before the procession and lasts through the night. Typically relatives and neighbors attend and food and alcoholic beverages are served.[4] The next morning at 10 A.M. the funeral procession begins. Coolies (laborers) are hired and divided into two groups; the rokushaku group carries the palanquin and coffin and the hirabito group carries the paper and fresh flowers and lanterns. Before departing for the temple the priest will chant sutras.[4] The order in which the procession proceeds is first those carrying the lanterns, then the flowers, then birds which are released to bring merit to the deceased, the incense burners, the memorial tablet, and then the coffin. Male relatives are the only people who carry items in the procession while the women ride in rickshaws following the coffin. The male heir of the deceased carries the memorial tablet, which is covered in thin silk. The men in the procession wear formal clothing with the family crest.[4] Initially, the family and neighbors would walk with the procession all the way to the temple, however during the Taishō era people would drop off from the procession along the way and take a train to the temple to wait for the procession to arrive. The family and close friends of the deceased would stay with the procession the entire way. The procession ends when it reaches the temple where the funeral will be held.[4]

During the Taishō era, funerals began to undergo many changes with one of the biggest ones being the elimination of the funeral procession. Funeral processions were extremely prominent during the Meiji era and part of the reason for ridding of them was to move away from the elaborateness of that time period and into more simplistic practices.[4] Another main reason for elimination of processions was the increase in public transportation and motorized vehicles, making the streets far too congested for large processions to occur.[4] As funeral practices moved away from the procession, kokubetsu-shiki (home farewell ceremonies) began to take their place. These ceremonies could be held at the family home, but sometimes were held at the funeral home or temple to replace the mourning that the funeral procession used to accomplish. These farewell ceremonies also served the purpose of offering condolence toward the grieving family in a social aspect.[4] With there no longer being a procession, the real and paper flowers that were carried began to be used to decorate the altar at the temple. The custom of placing a picture of the deceased on the altar also began during this period. Overall, the funeral procession changes were mainly attributed to "external societal conditions" rather than public opinions.[4]

Judaism

[edit]According to Jewish law, the deceased is to be buried as soon as possible so the time between death and burial is short. Burial cannot occur on the Sabbath or any Jewish holiday. The funeral service is brief and typically takes place at a funeral home, but sometimes is held at the synagogue or cemetery.[11] The funeral procession route goes from the funeral home or synagogue to the burial site and the pallbearers are the male family members and friends of the deceased.[12][11] It is traditional to stop seven times along the procession route at meaningful places to recite psalms. Psalm 91:1, "O thous that dwellest in the cover of the Most High" is a very common psalm to recite.[12] The practice of pausing seven times during the procession is derived from the funeral procession of the patriarch Jacob. During his funeral procession from Egypt to Canaan (Erets Yisrael - Land of Israel, later "Syria Palestina" circa 135 AD by Hadrian, Roman emperor after a failed rebellion of Judea against the Roman Empire), the group stopped for seven days to cross the Jordan River into the "Promised Land". These pauses along the way also serve to give the mourners a chance to stop at the different places to reflect on the life of the deceased.[12]

See also

[edit]- Corpse road

- Motorcade

- Jazz funeral

- Funeral train, using a railway train

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Richard., Rutherford (1990). The death of a Christian : the order of Christian funerals. Barr, Tony. (Rev. ed.). Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press. ISBN 0814660401. OCLC 23133769.

- ^ a b c d Sumegi, Angela (2014). Understanding Death: An Introduction to Ideas of Self and the Afterlife in World Religions. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 187–190.

- ^ a b c "Gandhi's son will light traditional funeral pyre". Ocala Star-Banner. 24 May 1991. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kōkyō, Murakami (2000). "Changes in Japanese Urban Funeral Customs during the Twentieth Century". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 27 (3/4). Nanzan University: 337–344. JSTOR 30233669.

- ^ a b Eck, Diana L. (1999). Banaras, city of light. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 324, 340. ISBN 0231114478. OCLC 40619497.

- ^ Smith, Bonnie G. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0195148909.

- ^ a b Michaels, Axel (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. Princeton University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0691089531.

- ^ Susai Anthony, Kenneth Schouler (2009). The Everything Hinduism Book: Learn the Traditions and Rituals of the "Religion of Peace". Everything Books. p. 251. ISBN 978-1598698626.

- ^ Bowen, Paul (1998). Themes and Issues in Hinduism. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 270. ISBN 0304338516.

- ^ a b c Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (2001). "Death, Funeral Processions, and the Articulation of Religious Authority in Early Islam". Studia Islamica (93). Maisonneuve & Larose: 27–58. doi:10.2307/1596107. JSTOR 1596107.

- ^ a b Weinstein, Lenore B. (Winter 2003). "Bereaved Orthodox Jewish Families and Their Community: A Cross-Cultural Perspective". Journal of Community Health Nursing. 20 (4): 237–238. doi:10.1207/S15327655JCHN2004_04. JSTOR 3427694. PMID 14644690. S2CID 44358710.

- ^ a b c G., Hoy, William. Do funerals matter? : the purposes and practices of death rituals in global perspective. New York. ISBN 9780203072745. OCLC 800035957.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)