French–Habsburg rivalry

The term French–Habsburg rivalry (French: Rivalité franco-habsbourgeoise; German: Habsburgisch-französischer Gegensatz) describes the rivalry between France and the House of Habsburg. The Habsburgs headed an expansive and evolving empire that included, at various times, the Holy Roman Empire, the Spanish Empire, Austria, Bohemia and Hungary from the Diet of Augsburg in the High Middle Ages until the dissolution of the monarchy following World War I in the late modern period.

In addition to holding the Austrian hereditary lands, the Habsburg dynasty ruled the Low Countries (1482–1794), Spain (1504–1700) and the Holy Roman Empire (1438–1806). All these lands were in personal union under Emperor Charles V. The expansion of the Habsburgs into western Europe increasingly led to border tensions with the Kingdom of France, which found itself encircled by Habsburg territory. The subsequent rivalry between the two powers became a cause for several conflicts. These include parts of the Anglo-French Wars (1066–1815), the War of the Burgundian Succession (1477–1482), the Italian Wars (1494–1559), the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), and the succession wars of Jülich (1609-1614), Mantua (1628–1631), Spain (1700–1713), Poland (1733–1736) and Austria (1740–1748).

Middle Ages

[edit]During the late Middle Ages, the Habsburgs, whose dominions consisted principally of Austria, and later Spain, sought alliances, principally through marriage, a policy which had the added benefit of gaining territory through marital inheritance. Territorial expansion in this way allowed the Habsburgs to gain territories throughout Europe[1] such as the Spanish Road, Burgundy, Milan and the Low Countries. This practice was described by Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus' quote: Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria, nube! – "Let others wage war. You, happy Austria, marry!"[2]

Following this tradition, Archduke Maximilian married Mary, the last Valois ruler of Burgundy and the Burgundian Netherlands, in 1477. Nineteen years later, their son Philip the Handsome married Joanna of Castile, who became heir to the Spanish thrones. Joanna and Philip's son, Charles, united all of these possessions in 1519. France had the Habsburgs on three sides as its neighbor, with Spain to the south, the Netherlands to the north, and the Franche-Comté to the east.

Early modern period

[edit]

Italian Wars

[edit]The Italian Wars were a long series of wars fought between 1494 and 1559 in Italy during the Renaissance. The Italian peninsula, economically advanced but politically divided between several states, became the main battleground for European supremacy. The conflicts involved the major powers of Italy and Europe, in a series of events that followed the end of the 40-year long Peace of Lodi agreed in 1454 with the formation of an Italic League.[3]

The collapse of the alliance in the 1490s left Italy open to the ambitions of Charles VIII of France, who invaded the Kingdom of Naples in 1494 on the ground of a dynastic claim. The French were however forced to leave Naples after the Republic of Venice formed an alliance with Habsburg Austria and Spain.[3]

An important consequence of the League of Venice was the political marriage arranged by Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor for his son, through Mary of Burgundy, Philip the Handsome who married Joanna the Mad (daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile) to reinforce the anti-French alliance between Austria and Spain. The son of Philip and Joanna would become Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 succeeding Maximilian and controlling an Habsburg empire inclusive of Castile, Aragon, Austria, and the Burgundian Netherlands, thus encircling France.

The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), which put an end to the Italian Wars, had mixed results: France renounced its claims to territories in Italy, but gained certain other territories, including the Pale of Calais and the Three Bishoprics.[4]

The Italian Wars also coincide with the Spanish conquest of Iberian Navarre, where France supported the King of Navarre (from the French House of Albret) against the Spanish Habsburgs. The result of this was the Spanish conquest of much Navarre south of the Pyrenees, but the French kept Navarre north of the Pyrenees. The Kingdom of Navarre would later be inherited by the Bourbons, and later united with France through personal union during the ascension of Henry IV.

French Wars of Religion

[edit]During the French Wars of Religion, France was split into several factions. Spain supported the French Catholics. In the Treaty of Joinville, Spain agreed to provide monetary and military support to the Catholic League. When the Protestant King of Navarre laid siege to Paris, Spanish commander, the Duke of Parma, helped relieve the city on behalf of the Catholics. Spain also occupied territory in Brittany during the Brittany Campaign. When the King of Navarre became King of France (as Henry IV), he declared war on Spain. This war was ended with the Peace of Vervins.

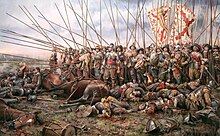

Thirty Years' War

[edit]

Even though the realm of Charles V was divided between the German and the Spanish branches of his dynasty in 1556, most of the territories of the Burgundian Inheritance, including the Netherlands, stayed with the Spanish crown, whereas the German regions remained with the Austrian branch of the dynasty within the Holy Roman Empire. France regarded the encirclement by the Habsburg powers as a permanent threat, and intervened in several years, to prevent Austro-Spanish domination in Europe. For example, in 1609, the death of John William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, led a succession dispute. When Archduke Leopold V was sent by Emperor Rudolf II to occupy Jülich in the name of the Emperor, French king Henry IV intervened to prevent the Habsburgs from gaining more influence by supporting the Protestant Union.[5] France also supported the protestant Dutch Republic in their independence struggle against Habsburg Spain.[6]

The Thirty Years' War began in 1618 as a result of conflict between the Protestant estates in Bohemia and their Catholic monarch Ferdinand II, who was heir to Austria. Ferdinand II was deposed as King of Bohemia and replaced by Frederick V of the Palatinate. Eventually, the conflict spread from an intrastate rebellion into a full-scale war between two religious groups: the Protestant North German states (which later included Denmark and Sweden); and the Catholic powers of the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs as well as the German Catholic League. France later joined the conflict, and like in the Jülich War and the 80 Years War, fought on the side of the Protestants in spite of the fact that France's national religion was Catholicism. This was for the political reason of attempting to prevent the Habsburgs from achieving total hegemony over the German lands.[7] French minister, Cardinal Richelieu, was the architect of much of France's foreign policy during this time.

Corresponding to the Thirty Years' War was the War of the Mantuan Succession, which erupted in 1628. France backed the Duke of Nevers, and the Habsburgs backed the Duke of Guastalla.[8] French success in this war, and the subsequent installation of Nevers as Duke of Mantua, weakened the Habsburg position in Italy.

After 1648, France became predominant in central Europe. Following the peace treaty of Munster in 1648 and, more particularly, the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659, Spain's power began its slow decline in what proved to be the last decades of a degenerating Habsburg regime there. After their victory over the Turks in the second Turkish siege of Vienna in 1683, the Austrian Habsburgs focused less and less on their conflicts with the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans.[9]

Nine Years' War

[edit]The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg[10] – was a conflict between Louis XIV of France and a European coalition of Austria, the Holy Roman Empire, the Dutch Republic, Spain, England and Savoy. It was fought in Europe and the surrounding seas, North America and in India. It is sometimes considered the first global war. The conflict encompassed the Williamite war in Ireland and Jacobite risings in Scotland, where William III and James II struggled for control of England and Ireland, and a campaign in colonial North America between French and English settlers and their respective Indigenous allies, today called King William's War by Americans.

Louis XIV had emerged from the Franco-Dutch War in 1678 as the most powerful monarch in Europe, an absolute ruler who had won numerous military victories. Using a combination of aggression, annexation, and quasi-legal means, Louis set about extending his gains to stabilize and strengthen France's frontiers, culminating in the brief War of the Reunions (1683–84). The Truce of Ratisbon guaranteed France's new borders for twenty years, but Louis's subsequent actions – notably his Edict of Fontainebleau (the revocation of the Edict of Nantes) in 1685 – led to the deterioration of his military and political dominance. Louis's decision to cross the Rhine in September 1688 was designed to extend his influence and pressure the Holy Roman Empire into accepting his territorial and dynastic claims. Leopold I and the German princes resolved to resist, and when the States General and William III brought the Dutch and the English into the war against France, the French king faced a powerful coalition aimed at curtailing his ambitions.[9]

The main fighting took place around France's borders in the Spanish Netherlands, the Rhineland, the Duchy of Savoy and Catalonia. The fighting generally favoured France's armies, but by 1696 his country was in the grip of an economic crisis. The Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) were also financially exhausted, and when Savoy defected from the Alliance, all parties were keen to negotiate a settlement. By the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick (1697) France retained the whole of Alsace but was forced to return Lorraine to its ruler and give up any gains on the right bank of the Rhine. Louis also accepted William III as the rightful king of England, while the Dutch acquired a barrier fortress system in the Spanish Netherlands to help secure their borders.[9]

War of Spanish Succession

[edit]

With the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in 1700, King Louis XIV of France claimed the Spanish throne for his grandson Philip V, which caused the War of the Spanish Succession. In the treaty of Utrecht, Louis succeeded in installing the Bourbon dynasty in a Spain that was by now a second-rank power, and in bringing the Habsburg encirclement of France to an end.

After two centuries, the rivalry had lost its original cause. After the potent decline of Spain, the 18th Century witnessed a major restructuring in European politics. Austria, the dominant power in Central Europe, now had to face the rising power of Prussia in the north. Russia finally grew to become a recognized great power after its success against Sweden in the Great Northern War. And last, Britain's ever-growing might in Europe and America finally challenged the hegemony that France had upheld for years. Nevertheless, the two powers remained hostile for several decades.

Diplomatic Revolution

[edit]Franco-Austrian Alliance

[edit]

A significant reversal in French–Habsburg relations known as the Diplomatic Revolution, occurred in 1756. In a move masterminded by Austrian diplomat Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz,[11] France and Austria became allies for the first time in over two hundred years. The alliance was sealed with the marriage of Austrian princess Marie Antoinette to the Dauphin of France, who later became King Louis XVI. The alliance was formalised with the signing of the First Treaty of Versailles in 1756.

The diplomatic change was triggered by a separation of interests between Austria and Britain. The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle which had concluded the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748 had left Maria Theresa of Austria dissatisfied with the British alliance. Despite having successfully defended her claim to the Habsburg throne and had her husband, Francis Stephen, crowned Emperor in 1745, she had been forced to relinquish valuable territory in the process. Under British diplomatic pressure, Maria Theresa had given up most of Lombardy and occupied Bavaria, as well as ceding Parma to Spain and the house of Bourbon. Finally, the valuable Bohemian crown land of Silesia had been given up to Frederick the Great, who had occupied it during the war. That acquisition had further advanced Prussia as a great European power, which now posed an increasing threat to Austria's central European position, and the growth of Prussia was welcomed by the British, who saw it as a means of balancing French power and reducing French influence in Germany, which might otherwise have grown in response to Austria's weakness. Conversely, the French, determined to impede further Prussian progress, were now willing to support Austria whose force had grown less intimidating.

Seven Years' War

[edit]

Several months after the signing of the treaty, the Seven Years' War, which involved Prussia, Great Britain, Russia, France, and Austria, broke out. France and Austria expanded upon the First Treaty with a further treaty concluded in 1757 and, along with Russia, fought against an alliance of Great Britain and Prussia, which was founded on the Westminster Convention of 1756.

Despite early successes in the war, the Franco-Austrian alliance did not prevail. The war ended in a victory for Britain and Prussia, aided by the miracle of the House of Brandenburg and Britain's control of the seas, and both France and Austria were left in weakened positions. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the war in 1763, established France's withdrawal from the American continent and consolidated Prussian gains in Europe to Austria's detriment.

Late modern period

[edit]French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

[edit]

The French Revolution was opposed by the Habsburgs in Austria, who sought to destroy the Revolutionary Republic with assistance from several coalitions of monarchical nations, including Britain and several states within the Holy Roman Empire. According to Chris McNab: "The problems faced by the Austrian Emperor were in large part due to past Habsburg successes. Primarily through marriages, they had acquired many provinces with varied ethnic and racial populations – therefore, no universal language existed in the army."[12] Due to difficulties such as this, the Austrian Army suffered defeats during the French Revolutionary and the Napoleonic Wars. After the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805 during the War of the Third Coalition, the ability of the Habsburgs to govern the Holy Roman Empire was dramatically weakened. This led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, which was divided between France and the newly formed Austrian Empire, leading to the formation of the Confederation of the Rhine. The Confederation was dissolved following Napoleon's defeat at the hands of the Sixth Coalition, which included Austria. Fighting between the two Empires resumed during the Hundred Days, which saw the seventh and final coalition emerge victorious over the French and an end to the Coalition Wars.

Franco-Austrian War

[edit]

The period immediately following the Bourbon Restoration was one of peace between France and Austria, as the two monarchies participated in the Quintuple Alliance in 1818. However, this alliance was dissolved following the death of Emperor Alexander I of Russia in 1825 and France's subsequent July Revolution of 1830, in which the Bourbon monarchy was overthrown. Hostilities between the two nations resumed during the Franco-Austrian War in 1859, Franco-Sardinian victory which resulted in the gains of Savoy and Nice for France, and the loss of Lombardy for Austria.

World War I

[edit]In the aftermath of the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, the Compromise of 1867 resulted in the creation of Austro-Hungarian Empire under the Habsburg Emperor. In 1879, Austria-Hungary entered into the Dual Alliance with the German Empire. In response, France entered into alliances with Russia and with the United Kingdom in 1894 and 1904 respectively. On 12 August 1914, the French Third Republic declared war on Austria-Hungary in response to Austria's declarations against Serbia and Russia. A western front against Austria-Hungary was opened upon its former ally, the Kingdom of Italy's entry into the war in 1915. Austro-Hungarian defeat resulted in it ceding Southern Tyrol to Italy through the Armistice of Villa Giusti signed 3 November 1918. At the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Charles I of Austria renounced participation in state affairs and the Habsburg Monarchy was officially brought to an end with the passing of the Habsburg Law by the Austrian Constitutional Assembly on 3 April 1919. France would play a major role in the creation of the postwar independent First Austrian Republic by insisting on forbidding Anschluss – or union with the Weimar Republic –in the Treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[13]

See also

[edit]- Anglo-French Wars

- Franco-Spanish War

- Austria–France relations

- French–German enmity

- Ottoman–Habsburg wars

References

[edit]- ^ 1. R. J. W. Evans, The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1550–1700: An Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), p. 93.

- ^ The World of The Hapsburgs. (2011). "Tu felix Austria nube 1430–1570". Retrieved from: http://www.habsburger.net/en/stories/tu-felix-austria-nube

- ^ a b Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy : a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present. New York, NY: Facts On File. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-8160-7474-7. OCLC 191029034.

- ^ ""Italian Wars"". Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Alison D. (1999). On the verge of war: international relations and the Jülich-Kleve succession crises (1609-1614). Studies in Central European histories. Boston: Humanities Press. ISBN 978-0-391-04092-2.

- ^ Gemeentearchief, Amsterdam (Netherlands); Scheltema, Pieter (1866). Inventaris van het Amsterdamsche Archief (in Dutch). Stads-Drukkerij.

- ^ Richard Bonney. (2010). The Thirty Years' War: 1618 – 1648. (London, Britain: Osprey Publishing). p. 7.

- ^ DAVID PARROTT, The Mantuan Succession, 1627–31: A Sovereignty Dispute in Early Modern Europe, The English Historical Review, Volume CXII, Issue 445, February 1997, Pages 20–65, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/CXII.445.20

- ^ a b c Lynn, John A. (1999). The wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714. Modern wars in perspective. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-05628-2.

- ^ Older texts may refer to the war as the War of the Palatine Succession, the War of the English Succession, or in North American historiography as King William's War. This varying nomenclature reflects the fact that contemporaries – as well as later historians – viewed the general conflict from particular national or dynastic viewpoints.

- ^ Franz A.J. Szabo, "Prince Kaunitz and the Balance of Power." International History Review 1#3 (1979): 399–408. in JSTOR

- ^ Chris McNab. (2011). Armies of the Napoleonic Wars. (London, Great Britain: Oxford Publishing). p. 168.

- ^ Steiner, Zara (2005). The lights that failed : European international history, 1919–1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-151881-2. OCLC 86068902.