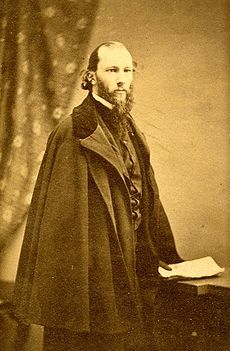

Frederic Beecher Perkins

Frederic Beecher Perkins | |

|---|---|

Frederic Beecher Perkins | |

| Born | 27 September 1828 |

| Died | 27 January 1899 (aged 70) |

| Occupation(s) | Librarian Writer Editor |

| Spouse | Mary Anne Wescott |

| Children | Thomas Adie Perkins Charlotte Perkins |

| Parent(s) | Thomas Clap Perkins and Mary Foote Beecher |

Frederic Beecher Perkins (27 September 1828 – 27 January 1899) was an American editor, writer, and librarian. He was a member of the Beecher family, a prominent 19th-century American religious family.

Early life

[edit]Frederic Beecher Perkins was born in Hartford, Connecticut, to Mary (Beecher) Perkins and Thomas Clap Perkins. He was the grandson of Lyman Beecher, a Presbyterian minister best known as a revivalist and social reformer.[1] He was also the father of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, a prominent American feminist, sociologist, novelist, and lecturer on social reform. Perkins entered Yale University in 1846 and though he left two years later before he finished his degree, Yale awarded him a Master of Arts degree in 1860.[2] In 1848, he worked in his father’s law office, and by 1851 Perkins was admitted to the Connecticut Bar. In 1852, Perkins graduated as a librarian from Connecticut Normal School,[3] now Central Connecticut State University, and became a teacher for a short time in Greenwich, Connecticut.[4] He held various posts in Hartford until 1854, in which year he went to New York City, remaining until 1857. Then, returning to Hartford, he became assistant editor of Henry Barnard's American Journal of Education for three years.

In 1857, Frederic was married to Mary Fitch Wescott, and together they had two children, Thomas Adie in 1859 and Charlotte in 1860. After Charlotte's birth, a physician advised Perkins that his wife's life would be in danger if she were to bear any more children. Soon, Perkins would leave his family, where they remained in an impoverished state.[5] Charlotte would go on and described her father as a "stranger" and states that he was "distant and little known". Though Perkins had abandoned his family, Charlotte noted gratitude towards her father, recognizing that "...by heredity I owe him much; the Beecher urge to social service, the Beecher wit and gift of words and such small sense of art as I have." Charlotte also reflected that he "took to books as a duck to water. He read them, he wrote them, he edited them, he criticized them, he became a librarian and classified them. Before he married he knew nine languages and continued to learn more afterward…In those days, when scholarship could still cover a large portion of the world’s good books, he covered them well."[6]

Librarianship

[edit]As a librarian, he worked at the Connecticut Historical Society from 1857 to 1861. In 1870, Perkins moved to Boston and began to work with his brother-in-law, Edward Everett Hale, as an editor for the magazine Old and New. In May 1874 Perkins was hired as office secretary at the Boston Public Library (BPL).[7] For a short time in 1879, Perkins became Assistant Librarian and Special Cataloger before resigning by December 1879.[8] While at the BPL, Perkins worked closely with Justin Winsor, contributing five articles to the 1876 report on public libraries. This would be a major influence in the field of library science and has been called the "magnum opus of library economy."[9] Perkins served as an editor for the Library Journal and the American Library Association Catalog, and was a founding member of the ALA's Cooperation Committee. After leaving the BPL, Perkins worked with Melvil Dewey at the Reader's and Writer's Economy Company. In 1880, he was appointed as head librarian of the San Francisco Public Library, where he served till 1887.[10]

Writings

[edit]He was editorially connected with various papers and magazines. Among his writings are:

- Scrope, or the Lost Library, a novel (Boston, 1874)

- My Three Conversations with Miss Chester (New York, 1877)

- Devil-Puzzlers, and other Studies (1877)

- Charles Dickens: his Life and Works (1877)

He also edited or compiled bibliographical works, for example:

- Check-List of American Local History (Boston, 1876)

- The Best Reading (1872; 4th ed., New York, 1877)

Notes

[edit]- ^

Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1888). "Perkins, Frederic Beecher". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1888). "Perkins, Frederic Beecher". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ Utley, George B. (1934). "Perkins, Frederic Beecher". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Kessler, Carol Farley, Ann J. Lane, and Sheryl L. Meyerling. To "Herland" and Beyond: The Life and Works of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. (1990): 158-161.

- ^ "Yale Obituary Record" (PDF).

- ^ Hill, Mary A. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Making of a Radical Feminist, 1860-1896 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980)

- ^ Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: An Autobiography. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1935.

- ^ See Boston Public Library, Boston Public Library Superintendent's Monthly Report 1873-1878, May 1874, No. 47.

- ^ Boston Public Library, 96.

- ^ Miksa, Francis, "The Making of the 1876 Special Report on Public Libraries", Journal of Library History, Philosophy, and Comparative Librarianship 8, no. 1 (1973): 30.

- ^ Murray, M. D. (2009). "Frederick Beecher Perkins: Library Pioneer and Curmudgeon". Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved 20 April 2017

References

[edit]- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.