Freddie Prinze

| Freddie Prinze Sr. | |

|---|---|

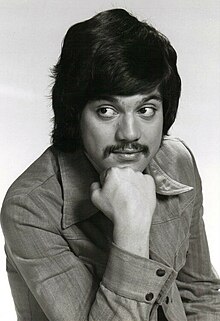

Prinze in 1975 | |

| Birth name | Frederick Karl Pruetzel |

| Born | June 22, 1954 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 29, 1977 (aged 22) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Medium | Stand-up, television |

| Years active | 1973–1977 |

| Genres | Observational comedy, blue comedy, deadpan, satire |

| Subject(s) | Latin American culture, recreational drug use, everyday life |

| Spouse |

Katherine Cochran (m. 1975) |

| Children | Freddie Prinze Jr. |

Frederick Karl Prinze Sr. (born Frederick Karl Pruetzel; June 22, 1954 – January 29, 1977) was an American stand-up comedian and actor, and the star of the NBC-TV sitcom Chico and the Man from 1974 until his death in 1977. He was described in a Vulture magazine article as "having blown up like no other comedian in history."[1] Prinze is the father of actor Freddie Prinze Jr.

Early life

[edit]Prinze was born Frederick Karl Pruetzel (German spelling: Prützel) at Saint Clare's Hospital in Manhattan, New York City,[2] the son of Maria de Gracia Pruetzel (née Graniela y Ramirez) and Edward Karl Pruetzel. His mother was a Puerto Rican Catholic and his father was a German[3] Lutheran immigrant who had arrived in the U.S. as a youth in 1934.[4] Prinze was raised in a mixed neighborhood in Washington Heights, New York City.[5] When Prinze was a small child, his mother enrolled him in ballet classes to deal with a weight problem. Without telling his parents, Prinze successfully auditioned for the High School of Performing Arts, where he was introduced to drama and continued ballet—and where he discovered his gift for comedy while entertaining crowds in the boys' restroom. He dropped out of school in his senior year to become a stand-up comedian.

Career

[edit]

Prinze worked at several comedy clubs in New York City, including The Improv and Catch a Rising Star, where he introduced himself to audiences as a "Hunga-rican" (part Hungarian, part Puerto Rican). Although his mother was in fact Puerto Rican, his father was a German immigrant with no Hungarian ancestry. Prinze's son, Freddie Prinze Jr., has stated many times that his father was half German/half Puerto Rican. This is also verified by census records as well as Prützel/Pruetzel family accounts. For the sake of his budding comedic career, he legally changed his surname to "Prinze". According to his friend David Brenner, Prinze originally wanted to be known as the king of comedy, but since Alan King already had that last name and sobriquet, he would be the prince of comedy instead. During 1973, Prinze made his first television appearance on one of the last episodes of Jack Paar Tonite. In December 1973, his biggest break came with an appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Prinze was the first young comedian to be asked to have a sit-down chat with Carson on his first appearance. Prinze appeared on and guest-hosted The Tonight Show on several other occasions. He also appeared on The Midnight Special to perform his comic routine.

From September 1974 until his death in January 1977, Prinze starred as Francisco "Chico" Rodriguez in the NBC TV series Chico and the Man with Jack Albertson. The show was an instant hit. Prinze made several appearances on The Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts, most notably the roasts for Sammy Davis Jr. and Muhammad Ali. In 1975, he released a comedy album that was taped live at Mister Kelly's in Chicago entitled Looking Good—his catch phrase from Chico and the Man. In 1976, he starred in a made-for-TV movie, The Million Dollar Rip-Off. Prinze had a little-known talent for singing, examples of which could be heard in the background of the title song of the Tony Orlando and Dawn album To Be With You, in his appearances on their variety show, and on rare occasions on his own sitcom. About four months before his death, Prinze signed a five-year deal with NBC worth $6 million.

Personal life

[edit]

On October 13, 1975, Prinze married Katherine "Kathy" Elaine (Barber) Cochran, with whom he had one child, son Freddie Prinze Jr., who was born March 8, 1976. Prinze was arrested for driving under the influence of Quaalude on November 16, 1976. A few weeks later his wife filed for divorce.

Prinze had been romantically linked to actresses Raquel Welch[6] and Pam Grier, whom he met in 1973.[7] Grier recalls their relationship in chapter nineteen of her memoir, My Life in Three Acts.[8] After his break-up with Grier, Prinze dated actress Lonette McKee for a time during 1976.[9] Prinze also dated Joanna Kerns a short time before he died. The two had worked together on the 1976 TV movie, The Million Dollar Rip-Off.[10]

Prinze was very close friends with singer Tony Orlando;[11] Orlando appeared on Chico and the Man, and Prinze appeared on Orlando's variety show.[12] As he started to make more money, Prinze took martial arts lessons from Robert Wall,[13] a student of Bruce Lee, who appeared in Enter the Dragon and The Way of the Dragon. Soon after, Wall became godfather to Prinze's newborn son.[14]

Death

[edit]Prinze suffered from depression. On the night of January 28, 1977, after talking on the telephone with his estranged wife, Prinze received a visit from his business manager, Marvin "Dusty" Snyder. During the visit, Prinze put a gun to his head and shot himself.[15] He had purchased this gun in the presence of fellow actors Jimmie "JJ" Walker and Alan Bursky, although it was long rumored that Bursky gave him the gun.[16] Prinze was rushed to the UCLA Medical Center and placed on life support following emergency surgery. His family removed him from life support, and he died at 1 p.m. on January 29.[17]

Prinze made farewell phone calls to numerous family members and friends prior to shooting himself and left a note stating that he had decided to kill himself.[18][19] In 1977, the death was ruled a suicide. However, in a 1983 civil case brought by his mother, wife, and son against Crown Life Insurance Company, the jury found that his death was medication-induced and accidental, which enabled the family to collect $200,000 in life insurance. This followed a $1 million out-of-court settlement with his psychiatrist and doctor to end a malpractice suit for allowing him access to a gun and overprescribing him Quaalude (as a tranquilizer).[20]

When Chico & the Man went into hiatus due to Prinze's death, a new mid-season series, which would go on to become highly successful, Three's Company, gave its star, John Ritter, Prinze's dressing room for its pilot episode.

Prinze is interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles, near his father, Edward Karl Pruetzel. His son, Freddie Prinze Jr., who was under one year old when his father died, did not speak publicly about his father's death until he discussed it in the documentary Misery Loves Comedy (2015), directed by Kevin Pollak.[21]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973–1974 | The Merv Griffin Show | Himself (Guest) | 3 episodes |

| 1973–1976 | The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson | Himself (Guest) | 20 episodes Guest (17 episodes) Guest Host (3 episodes) |

| 1974 | The Midnight Special | Himself | TV Special |

| 1974 | The Dean Martin Comedy World | Himself (Guest) | 2 episodes |

| 1974 | The Flip Wilson Special | Himself (Guest) | TV Special |

| 1974–1975 | The $25,000 Pyramid | Himself (Celebrity Contestant) | 2 episodes |

| 1974–1975 | The Mike Douglas Show | Himself (Guest) | 9 episodes |

| 1974–1976 | The Hollywood Squares | Himself (Panelist) | 5 episodes |

| 1974–1977 | Chico and the Man | Chico Rodriguez | series regular (62 episodes) Writer (1 episode) — #3.3 "Chico Packs His Bags" (written by) (1976) Nominated – Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Television Series — Comedy or Musical (1977)[22] |

| 1975 | The Smothers Brothers Show | Himself (Guest) | "Episode #1.2" |

| 1975 | The 1975 Annual Entertainment Hall of Fame Awards | Himself | TV Special |

| 1975 | Cher | Himself (Guest) | "Episode #1.5" |

| 1975–1976 | Dean Martin Celebrity Roast | Himself (Guest) | TV Special (2 episodes) — "Sammy Davis, Jr." (1975) — "Muhammad Ali" (1976) |

| 1975–1976 | Dinah! | Himself (Guest) | 6 episodes |

| 1975–1976 | Tony Orlando and Dawn | Himself (Guest) | 2 episodes |

| 1975 | American Bandstand | Himself (Guest) | "Episode #19.2" |

| 1976 | On Location: Freddie Prinze and Friends | Himself (Host) | TV Special (Also Writer) |

| 1976 | The Million Dollar Rip-Off | Muff Kovak | TV Movie |

| 1976 | Sammy and Company | Himself (Guest) | 2 episodes |

| 1976 | The Rich Little Show | Himself (Guest) | "Betty White and C.W. McCall" |

| 1976 | Joys! | Himself (Host) | TV Special |

| 1976 | From Montreal, the Bob Hope Olympic Benefit | Himself (Guest) | TV Special |

| 1976 | The Kelly Monteith Show | Himself (Guest) | "06.16.1976" |

| 1976 | The Great NBC Smilin' Saturday Mornin' Parade | Himself (Host) | TV Movie |

| 1976 | NBC: The First Fifty Years | Himself | TV Movie |

| 1976 | Van Dyke and Company | Himself | "Episode #1.7" |

| Archive Footage | |||

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

| 1978 | Chico and the Man | Chico Rodriguez | Uncredited "Raul Runs Away: Part 1" |

| 1988 | Hollywood Scandals and Tragedies | Himself | Direct-to-Video |

| 1992 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson | Himself | "The Last Tonight Show" |

| 1996 | Classic Stand-Up Comedy of Television | Himself | TV Special |

| 1998 | Behind the Music | Himself | "Tony Orlando" |

| 1998 | E! True Hollywood Story | Himself | Episode #2.28 "Freddie Prinze" |

| 2003 | 101 Most Shocking Moments in Entertainment | Himself | TV Movie |

| 2004 | 100 Greatest Stand-Ups of All Time | Himself (#49) | Miniseries |

| 2007 | Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project | Himself | TV Movie |

| 2009 | The Tragic Side of Comedy | Himself | TV Movie |

| 2016 | Entertainment Tonight | Himself | "06.11.2016" |

| 2016 | Extra | Himself | "06.11.2016" |

| 2017 | The History of Comedy | Himself | "One Nation, Under Comedy" |

| 2020 | Wait in the Wings | Himself | "Fame (1980): A Musical Revolution?" |

| 2020 | The Comedy Store | Himself | Miniseries (3 episodes) — #1.1 "Saw You Last Night on The Tonight Show" — #1.2 "The Comedy Strike" — #1.5 "The Birth of a Bit" |

| 2021 | History of the Sitcom | Himself | "Facing Race" |

| 2022 | Autopsy: The Last Hours of | Himself | "Freddie Prinze" |

| 2022 | Dark Side of Comedy | Himself | "Freddie Prinze" |

| 2023 | Dick Van Dyke 98 Years of Magic | Himself | TV Special |

Legacy

[edit]- Prinze's mother wrote a book about her son, The Freddie Prinze Story (1978).

- Can You Hear the Laughter? The Story of Freddie Prinze (September 1979) is a TV biopic.

- Prinze's life and death were a focal point of one of the storylines in the movie Fame (1980), set in Prinze's alma mater, the LaGuardia High School of Performing Arts.

- Prinze received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on December 14, 2004, honoring his contribution to the television industry.[23][24] Actor and comedian George Lopez has acknowledged that he paid for Prinze's star.

References

[edit]- ^ "Freddie Prinze Blew up Like No Other Comedian in History". February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze Biography". tracy_prinze.tripod.com. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Freddie Prinze, IMDb-Biography

- ^ Catalano, Grace (1999). Freddie Prinze Jr.: He's All That. New York City: Bantam Doubleday Dell Books for Young Readers. p. 7]. ISBN 978-0-440-22863-9.

- ^ Nordheimer, Jon (January 29, 1977). "Freddie Prinze Wounded in Head; Police Say TV Star Shot Himself; PRINZE, THE TV STAR, IS WOUNDED IN HEAD". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ "People Are Talking About". Jet. March 6, 1975.

- ^ Lee, Felicia R. (May 4, 2010). "Pam Grier's Collection of Lessons Learned". New York Times.

- ^ Grier, Pam (2010). Foxy: My Life in Three Acts. Springboard. ISBN 978-0-446-54850-2.

- ^ Henry, David; Henry, Joe (November 5, 2013). Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World that Made Him. Algonquin Books. ISBN 978-1-61620-271-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Talk".

- ^ Ross, Scott. "Tony Orlando's Brush With Death". Christian Broadcasting Network. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "The Bootleg Files: Chico and the Man". filmthreat.com. October 31, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn (December 10, 1975). "Marilyn Beck (column)". Orlando Sentinel. p. 110. Retrieved March 29, 2018 – via newspaper.com.

- ^ "Martial arts master went toe to toe with greatest". Albuquerque Journal. August 5, 2011. p. 48. Retrieved March 29, 2018 – via newspaper.com.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze: Too Much, Too Soon". Time. February 7, 1977. Archived from the original on January 30, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ Keller, Joel (October 5, 2020). "Stream It Or Skip It: 'The Comedy Store' On Showtime, A Docuseries About The Sunset Strip Comedy Club Where Legends Were Born". Decider.

- ^ Scott, Vernon (January 31, 1977). "Freddie Prinze buried on hill overlooking NBC studio". The Capitol Journal. Salem, Oregon. UPI. p. 6. Retrieved March 29, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Museum of Broadcast Communications". Museum.tv. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Wilkins, Frank. "The Suicide Death of Freddie Prinze". Reel Reviews. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze death ruled an accident". UPI. January 20, 1983.

- ^ Evry, Max (April 23, 2015). "Interview: Kevin Pollak Tells Us Why Misery Loves Comedy". comingsoon.net. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze". Golden Globes. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze | Hollywood Walk of Fame". www.walkoffame.com. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze – Hollywood Star Walk – Los Angeles Times". projects.latimes.com. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Grier, Pam (2010). Foxy: My Life in Three Acts. with Andrea Cagan. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-54850-2.

- Pruetzel, Maria (1978). The Freddie Prinze Story. Master's Press. ISBN 0-89251-051-X.

External links

[edit]- 1954 births

- 1977 deaths

- American actors of Puerto Rican descent

- American stand-up comedians

- American male television actors

- Hispanic and Latino American male actors

- American people of German descent

- People from Washington Heights, Manhattan

- Male actors from Manhattan

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- 20th-century American male actors

- Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School alumni

- 20th-century American comedians

- American male comedians

- Comedians from Manhattan

- Suicides by firearm in California

- Hispanic and Latino American male comedians

- 1977 suicides