Friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide[a] is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy or hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while engaging an enemy, long range ranging errors or inaccuracy. Accidental fire not intended to attack enemy or hostile targets, and deliberate firing on one's own troops for disciplinary reasons is not called friendly fire,[1] and neither is unintentional harm to civilian or neutral targets, which is sometimes referred to as collateral damage.[2] Training accidents and bloodless incidents also do not qualify as friendly fire in terms of casualty reporting.[3]

Use of the term friendly in a military context for allied personnel started during the First World War, often when shells fell short of the targeted enemy.[4] The term friendly fire was originally adopted by the United States military; S.L.A. Marshall used the term in Men Against Fire in 1947.[5] Many North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) militaries refer to these incidents as blue on blue, which derives from military exercises where NATO forces were identified by blue pennants and units representing Warsaw Pact forces by red pennants. In classical forms of warfare where hand-to-hand combat dominated, death from a "friendly" was rare, but in industrialized warfare, deaths from friendly fire are more common.[6]

Friendly fire should not be confused with fragging, which is the uncondoned intentional (or attempted) killing of servicemen by fellow personnel serving on the same side.

History

[edit]Paul R. Syms argues that friendly fire is an ancient phenomenon.[7] He notes recorded events in Ancient Greece and other early accounts of battles. He and other historians also note that weapons such as guns, artillery, and aircraft dramatically increased friendly-fire casualties.

By the 20th and 21st centuries, friendly-fire casualties have likely become a significant percentage of combat injuries and fatalities. Jon Krakauer provides an overview of American casualties during and since the Second World War:

While acknowledging that the "statistical dimensions of the friendly fire problem have yet to be defined; reliable data are simply not available in most cases," The Oxford Companion to American Military History estimates that between 2 percent and 25 percent of the casualties in America's wars are attributable to friendly fire.[8]

Under-reporting

[edit]In the annals of warfare, deaths at the hand of the enemy are often valorized, while those at the hand of friendly forces may be cast in shame. Moreover, because public relations and morale are important, especially in modern warfare, the military may be inclined to under-report incidents of friendly-fire, especially when in charge of both investigations and press releases:

If fratricide is an untoward but inevitable aspect of warfare, so, too, is the tendency by military commanders to sweep such tragedies under the rug. It's part of a larger pattern: the temptation among generals and politicians to control how the press portrays their military campaigns, which all too often leads them to misrepresent the truth in order to bolster public support for the war of the moment.

— Jon Krakauer, Where Men Win Glory. NY: Bloomsbury, p. 205.

Although there may well be a longstanding history of such bias,[9][10] Krakauer claims "the scale and sophistication of these recent propaganda efforts, and the unabashedness of their executors" in Iraq and Afghanistan is new.[11]

Causes

[edit]Fog of war

[edit]Friendly fire can arise from the "fog of war" – the confusion inherent in warfare. Friendly fire that is the result of apparent recklessness or incompetence may be improperly lumped into this category. The concept of a fog of war has come under considerable criticism, as it can be used as an excuse for poor planning, weak or compromised intelligence and incompetent command.[1]

Errors of position

[edit]Errors of position occur when fire aimed at enemy forces may accidentally end up hitting one's own. Such incidents are exacerbated by close proximity of combatants and were relatively common during the First and Second World Wars, where troops fought in close combat and targeting was relatively inaccurate. As the accuracy of weapons improved, this class of incident has become less common but still occurs.

Errors of identification

[edit]Errors of identification happen when friendly troops are mistakenly attacked in the belief that they are the enemy. Highly mobile battles, and battles involving troops from many nations are more likely to cause this kind of incident as evidenced by incidents in the 1991 Gulf War, or the shooting down of a British aircraft by a U.S. Patriot battery during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[12] In the Tarnak Farm incident, four Canadian soldiers were killed and eight others injured when a U.S. Air National Guard major dropped a 500 lb (230 kg) bomb from his F-16 onto the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry regiment which was conducting a night firing exercise near Kandahar.[13][14] Another case of such an accident was the death of Pat Tillman in Afghanistan, although the exact circumstances of that incident are yet to be definitively determined.[15]

During World War II, "invasion stripes" were painted on Allied aircraft to assist identification in preparation for the invasion of Normandy. Similar markings had been used when the Hawker Typhoon was first introduced into use as it was otherwise very similar in profile to a German aircraft. Late in the war the "protection squadron" that covered the elite German jet fighter squadron as it landed or took off were brightly painted to distinguish them from raiding Allied fighters.

Errors of response inhibition

[edit]Errors of response inhibition have recently been proposed as another potential cause of some friendly fire accidents.[16][17] These types of errors are different from visual misidentification, and instead appear to be caused by a failure to inhibit a shooting response.

A number of situations can lead to or exacerbate the risk of friendly fire. Difficult terrain and visibility are major factors. Soldiers fighting on unfamiliar ground can become disoriented more easily than on familiar terrain. The direction from which enemy fire comes may not be easy to identify, and poor weather conditions and combat stress may add to the confusion, especially if fire is exchanged. Accurate navigation and fire discipline are vital. In high-risk situations, leaders need to ensure units are properly informed of the location of friendly units and must issue clear, unambiguous orders, but they must also react correctly to responses from soldiers who are capable of using their own judgement. Miscommunication can be deadly. Radios, field telephones, and signalling systems can be used to address the problem, but when these systems are used to co-ordinate multiple forces such as ground troops and aircraft, their breakdown can dramatically increase the risk of friendly fire. When allied troops are operating, the situation is even more complex, especially with language barriers to overcome.[18]

Impact reduction

[edit]Some analyses dismiss the material impact of friendly fire, by concluding friendly-fire casualties are usually too few to affect the outcome of a battle.[19][20] The effects of friendly fire, however, are not just material. Troops expect to be targeted by the enemy, but being hit by their own forces has a huge negative impact on morale. Forces doubt the competence of their command, and its prevalence makes commanders more cautious in the field.[21]

Attempts to reduce this effect by military leaders involve identifying the causes of friendly fire and overcoming repetition of the incident through training, tactics and technology.[18]

Training

[edit]

Most militaries use extensive training to ensure troop safety as part of normal coordination and planning, but are not always exposed to possible friendly-fire situations to ensure they are aware of situations where the risk is high. Difficult terrain and bad weather cannot be controlled, but soldiers must be trained to operate effectively in these conditions, as well as being trained to fight at night. Such simulated training is now commonplace for soldiers worldwide. Avoiding friendly fire can be as straightforward as ensuring fire discipline is instilled in troops, so that they fire and cease firing when they are told to. Firing ranges now also include "don't fire" targets.[21]

The increasing sophistication of weaponry, and the tactics employed against American forces to deliberately confuse them has meant that while overall casualties have fallen for American soldiers in the late 20th and 21st centuries, the overall percentage of deaths due to friendly fire in American actions has risen dramatically. In the 1991 Gulf War, most of the Americans killed by their own forces were crew members of armored vehicles hit by anti-tank rounds. The response in training includes recognition training for Apache helicopter crews to help them distinguish American tanks and armored vehicles at night and in bad weather from those of the enemy. In addition, tank gunners must watch for "friendly" robotic tanks that pop out on training courses in California's Mojave Desert. They also study video footage to help them recognize American forces in battle more quickly.[22]

Technological fixes

[edit]Improved technology to assist in identifying friendly forces is also an ongoing response to friendly fire problems. From the earliest days of warfare, identification systems were visual and developed into extremely elaborate suits of armour with distinctive heraldic patterns. During the Napoleonic Wars, Admiral Nelson ordered that ships under his command adopt a common paint scheme to reduce friendly fire incidents; this pattern became known as the Nelson Chequer. Invasion stripes served a similar function during the Allied invasion of Normandy in World War II. When radar was developed during World War II, IFF ("Identification friend or foe") systems to identify aircraft developed into a multitude of radio beacons.

Correct navigation is vital to ensuring units know where they are in relation to their own force and the enemy. Efforts to provide accurate compasses inside metal boxes in tanks and trucks has proven difficult, with GPS a major breakthrough.

Other technological changes include hand-held navigational devices that use satellite signals, giving ground forces the exact location of enemy forces as well as their own. The use of infrared lights and thermal tape that are invisible to observers without night-goggles, or fibres and dyes that reflect only specific wavelengths are developing into key identifiers for friendly infantry units at night.

There is also some development of remote sensors to detect enemy vehicles – the Remotely Monitored Battlefield Sensor System (REMBASS) uses a combination of acoustic, seismic vibration, and infrared to not just detect, but identify vehicles.[21]

Tactics

[edit]Some tactics make friendly fire virtually inevitable, such as the practice of dropping barrages of mortars on enemy machine gun posts in the final moments before capture. This practice continued throughout the 20th century since machine guns were first used in World War I. The high friendly fire risk has generally been accepted by troops since machine gun emplacements are tactically so valuable, and at the same time so dangerous that the attackers wanted them to be shelled, considering the shells far less deadly than the machine guns.[21] Tactical adjustments include the use of "kill boxes", or zones that are placed off-limits to ground forces while allied aircraft attack targets, which goes back to the beginning of military aircraft in World War I.[22]

The shock and awe battle tactics adopted by the American military – overwhelming power, battlefield awareness, dominant maneuvers, and spectacular displays of force – are employed because they are believed to be the best way to win a war quickly and decisively, reducing casualties on both sides. However, if the only people doing the shooting are American, then a high percentage of total casualties are bound to be the result of friendly fire, blunting the effectiveness of the shock and awe tactic. It is probably the fact that friendly fire has proven to be the only fundamental weakness of the tactics that has caused the American military to take significant steps to overturn a blasé attitude to friendly fire and assess ways to eliminate it.[21]

Markings

[edit]During Operation Husky, codename for the Allied invasion of Sicily, on the night of 11 July 1943, American C-47 transport planes were mistakenly fired upon by American ground and naval forces and 23 planes were shot down and 37 damaged, resulting in 318 casualties, with 60 airmen and 81 paratroopers killed.[23]

This led to the use of Invasion stripes that were used during D-Day as a visible way to prevent friendly fire.[24] During the Russian invasion of Ukraine the Z (military symbol) has been used on Russian vehicles as a form of marking. There are various explanations as to its meaning, however, one is that both sides are using the same equipment. Ukrainian forces have responded by using visible Ukrainian flags on their vehicles.[25] The picture has become more confused as both sides are using captured or abandoned equipment with Ukraine using captured Russian tanks.[26][27]

Examples

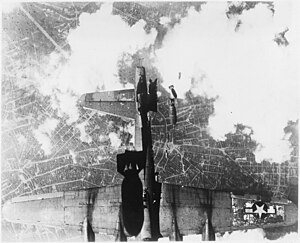

[edit]Incidents include: the killing of Royalist commander, the Earl of Kingston, by Royalist cannon fire during the English Civil War;[28] the bombing of American troops by Eighth Air Force bombers during Operation Cobra in World War II;[29] the attack on the Royal Navy 1st Minesweeping Flotilla off Cap d'Antifer, Le Havre by 263 Squadron and 266 Squadron RAF on 27 August 1944, sinking HMS Britomart and Hussar, and irreparably damaging HMS Salamander, killing 117 sailors and wounding 153 more;[30] the eight-hour firefight between British units during the Cyprus Emergency;[31] the sinking of the German destroyers Leberecht Maass and Max Schultz by the Luftwaffe in the North Sea during World War II; the downing of a British Army Gazelle helicopter by a British warship during the Falklands War;[32] the downing of two U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters by USAF fighters in 1994 during the Iraqi no-fly zones;[33] the shooting down and killing of Italo Balbo, the Italian governor of Libya over Tobruk by Italian anti aircraft fire in 1940; the accidental shooting of Stonewall Jackson during the American Civil War; the killing of a Royal Military Policeman by a British sniper during the war in Afghanistan;[34] and the Tarnak Farm incident when US Air National Guard pilots in 2002 bombed 12 Canadian soldiers, four of whom were killed;[35] these were the first Canadian casualties of the war in Afghanistan.

See also

[edit]- A Second Knock at the Door (2011 documentary film)

- Friendly Fire, 1979 television docudrama about a high-profile friendly fire incident during the Vietnam War

- Identification friend or foe (IFF), aviation technology

Notes

[edit]- ^ From the term for killing one's brother

References

[edit]- ^ a b Regan, Geoffrey (2002) Backfire: a history of friendly fire from ancient warfare to the present day, Robson Books

- ^ Rasmussen, Robert E. "The Wrong Target – The Problem of Mistargeting Resulting in Fratricide and Civilian Casualties" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ Joint Chiefs of Staff. "Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 20 November 2010 (As amended through 31 January 2011)" (PDF). p. 149. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. cites a 1925 reference to a term used in trenches during the war

- ^ Marshall, S.L.A. (1947). Men Against Fire. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 193.

- ^ Shrader 1982, vii

- ^ Kirke, Charles (ed.). 2010. Fratricide in Battle: (Un)Friendly Fire. London: Bloomsbury, p. 7.

- ^ Krakauer, Jon. 2010. Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman, NY: Anchor Books, p. 405.

- ^ Claire Outteridge, Simon Henderson, Raphael Pascual, Paul Shanahan, "How can Human Factors be Exploited to Reduce the Risk of Fratricide?" in Kirke, p. 115

- ^ Krakauer, Jon. 2009. Where Men Win Glory. NY: Bloomsbury, p. 204.

- ^ Krakauer, Jon. 2009. Where Men Win Glory. NY: Bloomsbury, p. 205.

- ^ The Economist Closing in on Baghdad 25 March 2003

- ^ Friscolanti, Michael. (2005). Friendly Fire: The Untold Story of the U.S. Bombing that Killed Four Canadian Soldiers in Afghanistan. pp. 420–421

- ^ CBC News Online (6 July 2004). "U.S. Air Force Verdict." Archived 4 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "U.S. military probes soldier's death". CNN. 1 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ Biggs, A. T., Cain, M. S., & Mitroff, S. R. (2015). Cognitive training can reduce civilian casualties in a simulated shooting environment. Psychological science, 26(8), 1164–1176. doi:10.1177/0956797615579274

- ^ Wilson, K. M., Head, J., de Joux, N. R., Finkbeiner, K. M., & Helton, W. S. (2015). Friendly fire and the sustained attention to response task. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, doi:10.1177/0018720815605703

- ^ a b Kirke, Charles M. (ed., 2012) Fratricide in Battle: (Un)Friendly Fire Continuum Books Archived 11 October 2017 at Archive-It

- ^ (in French) Percin, Gen. Alexandre (1921) Le Massacre de Notre Infanterie 1914–1918, Michel Albin, Paris;

- ^ Shrader, Charles R. (1982) Amicicide: The Problem of Friendly Fire in Modern War, US Command & General Staff College Survey No. 1

- ^ a b c d e Office of Technology Assessment (1993). Who goes there : friend or foe?. Diane Publishing. ISBN 9781428921139. Retrieved 4 January 2011.[page needed]

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric (9 December 1991). "U.S. Striving to Prevent 'Friendly Fire'". The New York Times. Middle East. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ^ "Airborne Reinforcement". US Army in World War II. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "The History of Invasion Stripes". Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Tiwari, Sakshi (19 April 2022). "Russia Starts Erasing 'Z' – The Infamous Ukraine Invasion Symbol From Their Tanks & Armored Vehicles – Kiev". Latest Asian, Middle-East, Eurasian, Indian News. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "The Ukrainian Army Has More Tanks Now Than When The War Began – Because It Keeps Capturing Them From Russia". Forbes. 24 March 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia restoring captured, damaged Ukrainian tanks, vehicles – report". The Jerusalem Post. 17 April 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Brett, Simon (2017). Seriously Funny, and Other Oxymorons. Hachette UK. p. 43. ISBN 9781472139443. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (6 June 2016). "The little known D-Day operation that accidentally killed more than 100 U.S. troops". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "Sinking of HMS Britomart and HMS Hussar by friendly fire". Halcyon Class. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ van der Bijl, Nicholas (2014). The Cyprus Emergency: The Divided Island 1955–1974. Pen and Sword. p. 109. ISBN 9781844682508.

- ^ "London Calling the Falklands Islands, Friendly Fire". BBC Programmes. BBC. 7 January 2003. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Wrage, Stephen; Cooper, Scott (2019). No Fly Zones and International Security: Politics and Strategy. Routledge. pp. 34–36. ISBN 9781317087182. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Doward, Jamie (14 November 2010). "Sniper escapes prosecution over friendly fire death". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Yaniszewski, Mark (2007). "Reporting on Fratricide: Canadian Newspapers and the Incident at Tarnak Farm, Afghanistan". International Journal. 62 (2). Sage Publications, Ltd.: 362–380. doi:10.1177/002070200706200210. JSTOR 40204274. S2CID 141837377.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Earl R. (2017) Friendly Fire in the Literature of War, Jefferson NC: McFairland [ISBN missing]

- Garrison, Webb B. (1999) Friendly Fire in the Civil War: More than 100 True Stories of Comrade Killing Comrade, Rutledge Hill Press, Nashville, TN; ISBN 1558537147

- Kemp, Paul. (1995) Friend or Foe: Friendly Fire at Sea 1939–45, Leo Cooper, London; ISBN 0850523850

- Kirke, Charles M. (ed., 2012) Fratricide in Battle: (Un)Friendly Fire, Continuum Books; ISBN 9781441157003

- (in French) Percin, Gen. Alexandre (1921) Le Massacre de Notre Infanterie 1914–1918, Michel Albin, Paris; OCLC 924214914

- Regan, Geoffrey (1995) Blue on Blue: A History of Friendly Fire, Avon Books, NY; ISBN 0380776553

- Regan, Geoffrey (2004) More Military Blunders, Carlton Books ISBN 9781844427109

- Shrader, Charles R. (1982) Amicicide: The Problem of Friendly Fire in Modern War Archived 20 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, US Command & Staff College, Fort Leavenworth: University Press of the Pacific, 2005; ISBN 1410219917

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Friendly fire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Friendly fire at Wikimedia Commons