Frankopan family

| Frankopan | |

|---|---|

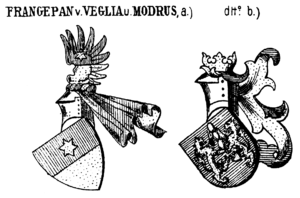

The older (left) and later (right) coat of arms | |

| Country | Kingdom of Croatia Republic of Venice |

| Founded | 1118[1] |

| Founder | Dujam I Krčki[2] |

| Final ruler | Fran Krsto Frankopan[2] |

| Titles | Count of Krk, Modruš, Senj and Tržac[3] Ban of Croatia[2] |

| Dissolution | 1671[1] |

The House of Frankopan (Croatian: Frankopani, Frankapani, Italian: Frangipani, Hungarian: Frangepán, Latin: Frangepanus, Francopanus) was a Croatian noble family, whose members were among the great landowner magnates and high officers of the Kingdom of Croatia in union with Hungary.

The Frankopans, along with the Zrinskis, are among the most important and most famous Croatian noble families who, from the 11th to the 17th century, were very closely connected with the history, past and destiny of the Croatian people and Croatia. For centuries, members of these noble clans were the bearers and defenders of Croatia against the Ottomans, but also resolute opponents of the increasingly dangerous Habsburg imperial absolutism and German hegemony, which in the spirit of European mercantilism sought to consolidate throughout the Habsburg Monarchy. The past of these two clans is intertwined with marital ties, friendships and participation in almost all significant events in Croatia, especially on the battlefields in the defense of Croatia from the Ottoman conqueror.[4]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The Frankopan family was one of the leading Croatian aristocratic families from the 12th to the 17th century. Since the 15th century they were trying to link themselves to the Roman patrician Frangipani family (which claimed descent from a Roman plebeian family of Anicii and ended in 1654 with Mario Frangipane being its last male descendant[5]). However Croatian Encyclopedia,[4] Italian Encyclopedia[6] and German Biographical Lexicon of the History of Southeastern Europe[7] by the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies highly question the bloodline connection between the two families and remind of the common fashion of medieval noble families in Europe to try and connect themselves to ancient Roman nobility. Along with the members of the Zrinski family the Frankopan ranked high in terms of importance by virtue of power, wealth, fame, glory and role in Croatian and Hungarian history. The first known member of Croatian lineage of the Frankopan family was Dujam I Krčki (Doymus Veglenfis in Latin sources that also attribute the title of comes to him[8][9]), lord of Krk who received permission by Domenico Michieli, Doge of Venice from 1118 to 1130, to rule the island of Krk as vassal of the Republic of Venice.[4][2] His exact origin is unknown, but he and his descendants were referred to as the Counts of Krk in historical documents.[4][6][2] In 1221, the brothers Henry and Servidon Frankopan received the islands of Brač, Hvar, Korčula and Lastovo as a gift from King Andrew II of Hungary for their services.[10] In 1428 Nikola IV Krčki (Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia from 1426 to 1432) was the first of the Counts of Krk to call himself Frankapan.[11] In 1430 he managed to receive recognition from Pope Martin V for being a descendant of the old Roman patrician family Frangipani and officially started using the name and coat of arms Frangipani.[1][11]

In 1240–1241 the Mongol Empire advanced from Poland toward Hungary whose King, Béla IV resisted bravely but finally had to seek refuge in Dalmatia. King Béla stayed with the Frankopans who assisted him with arms and funds and brought him into safety in Veglia and then brought him back to his own land. As reward the King gave the Frankopans the county of Senj with surrounding lands and the castle of Modruš.[12]

In 1246 there was another war, between Frederick II, Duke of Austria and Béla, who, with the assistance of the Frankopan, won a victory. As a further reward, King Béla then, by royal decree, created the Frankopans as Lords of their territory for them and their descendants.[12]

The Frankopans constantly supported the Catholic Church. In particular, Nikola Frankopan reconstructed the Holy House of Our Lady in 1294 in Tersatto (Trsat).[12] It is recorded that in 1291, Nikola Frankopan sent a delegation to Nazareth to measure the Holy House after the House had been saved, presumably by the Crusaders, and brought to Trsat or Tersatto, on the Adriatic Coast where the Frankopans had a castle. In 1294 Nikola Frankopan, gave the Holy House to the Pope to be placed on Papal lands, at Loreto, near Ancona.

Although the possessions of the family were exposed to every assault both from the east and the west, their power increased steadily until the 17th century when their lands reached further east. The Zrinski and Frankopan families came into closer affinity by marriage ties until in the eyes of the European courts they had become one of the most important families of Croatia.

In 1420 the Swedish King Erik of Pomerania called Ivan VI Frankopan, the eldest son of the Croatian ban Nikola IV, to Sweden to accompany the Swedish King to the Holy Land and later to assist the King at the Court in Sweden. Ivan VI Frankopan lived in Sweden at intervals between 1420 and 1430. After his father's death he returned to his home country. His eldest son called Matthias (Matija)[13] stayed in Sweden.

In 1425 Emperor Sigismund confirmed the noble status of Nikola Frankopan referring to him as Niklas Frangiapan Comes de Begle, Segnie et Modrusse (Nikola Frankopan, Count of Krk, Senj and Modruš)[14][15] using the Latin title of comes. He also granted the family the privileges of red wax, (Rotwachsprivilegien), i.e., the right to use red wax for their seals. Sigismund underlines at the end of this document that no one must ever dispute these rights of the family.[16]

Bernardin Frankopan's (1453–1529) paternal grandmother Dorothy was from a prominent Hungarian noble family, Garay, while his mother Isotta from Este family was Duchy of Ferrara of Ferrara. Through ancestry from royal Spanish families Bernardin had even Árpád ancestry (the Árpád dynasty founded the Kingdom of Hungary.) The Frankopan family was persecuted after the Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy, where the Count Fran Krsto Frankopan participated in an uprising against Habsburg King Leopold I. He and his brother-in-law, Petar Zrinski were executed in Wiener Neustadt.

The line of Stjepan II Frankopan, Ban of Croatia (d. 1481), died out with Katarina Frankopan in the 16th century. The line of Sigismund Frankopan expired with Franjo Frankopan, Bishop of Eger in 1542. Another branch died out in 1572 with Franjo Frankopan, Ban of Croatia; and the Trsat branch died out with Fran Krsto Frankopan in 1671 (and in the female line with Maria Juliana Frankopan, married Countess of Abensberg und Traun and later Countess von Attems).[3]

Doimi de Lupis's name claiming

[edit]In 1991,[17] Vjekoslav Nikola Antun Doimi de Lupis (1939–2018),[18] originally also Dujmić-Vukasinović,[19] by then a British citizen, changed his name and surname to "Louis Doimi de Frankopan Šubić Zrinski" or "Louis Michal Antun Doimi de Lupis de Frankopan Shubich Zrinski" under British Civil law,[18][20][21] adding several names of ancient Croatian noble families that combined in such a fashion were historically never attributed to any member of mentioned noble families.[19] In the late 1990s, Louis's cousin Mirko Jamnicki-Dojmi di Delupis wrote an open letter where he denounced claims over Frankopan, Šubić and Zrinski names by his family and presented the family tree of Dojmi di Delupis containing 129 names from the year 1200 onwards.[22] Louis's descendants include Lady Nicholas Windsor,[23] and historian Peter Frankopan who also claimed that they always had the same name.[24]

In 2002, the wife of Louis Doimi de Lupis, Swedish lawyer Ingrid Detter, bought the Ribnik Castle, once the property of the Frankopans, and today in the Register of Cultural Goods of Croatia (Z-301), for the price of 1.6 million kunas from the Ribnik municipality and in accordance with the decision of the Ministry of Culture, the Directorate for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, however hardly anything has been invested.[18][25][26][27] In 2003, they also founded the literary awards "Katarina Zrinska" and "Petar Zrinski", which were held only once. In the same year, during the Pope John Paul II visit of The Shrine of Our Lady of Trsat, which was tightly related to the Frankopan family, the members of de Lupis family managed to get presented not by their original name yet as Frankopans.[19][17]

Notable members

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

- Dujam II of Krk (ruled c. 1288–1317)

- Bartolomeo VIII Frankopan of Krk and Senji (ruled 1327–1361), in 1336 helped free the future Czech King Charles IV from capturing by pirates[28]

- Ivan V (Anž) of Krk (died 1393), Ban of Croatia

- Nikola IV Frankopan (c.1360–1432), first "Frankopan" and son of Ivan V of Krk also Ban of Croatia

- Ivan VI Frankopan (Hungarian: János) (died 1436), son of Nikola IV Frankopan and Ban of Croatia

- Stjepan III Frankopan (Hungarian: István) (c. 1416–1481 or 1484), son of Nikola IV Frankopan. Co-ruled with Ban Ivan VI Frankopan.

- Ivan VII Frankopan, ruled the Principality of Krk between 1451 and 1480.

- Bernardin Frankopan (1453–1529) Son of Stjepan III Frankopan. Influential nobleman, diplomat, and warrior.

- Nikola V Frankopan (died 1456–1458), son of Nikola IV Frankopan and Ban of Croatia and Slavonia

- Beatrice Frankopan (1480–c. 1510), heiress of Hunyad Castle and wife of John Corvinus

- Krsto Frankopan (1482–1527), son of Bernardin Frankopan and Ban of Croatia

- Juraj III Frankopan (?–1553), signatory of Cetingrad Charter (1527)

- Franjo Frankopan (1536 – 1572), Ban of Croatia

- Vuk II Krsto Frankopan (c. 1578–c. 1652), general of Karlovac generalate

- Franjo Frankopan Cetinski, archbishop, bishop, and diplomat

- Nikola IX Frankopan of Tržac (died 1647), Ban of Croatia

- Katarina Zrinska (c.1625–1673), daughter of Vuk Krsto Frankopan. Married Petar Zrinski, Ban of Croatia.

- Fran Krsto Frankopan (beheaded in 1671), promulgated the Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy, known as Wesselényi conspiracy in Hungary.

Holdings

[edit]Several of the Frankopan castles remain in Croatia, mostly around the Gorski kotar region and the island of Krk. The castle at Stara Susica near Trsat incorporates structures going back to the Illyrian and Roman periods. The town of Bosiljevo has a medieval fortified castle, renovated in the last century in the spirit of the Romanesque. The castle and park at Severin na Kupi were owned by the Frankopan family until the mid-17th century. Other castles or property of the Frankopans could be found in Ribnik, Bosiljevo, Novi Vinodolski, Drivenik, Ogulin, Slunj, Ozalj, Cetingrad, Trsat, and other surrounding towns. The Frankopan castle in the town of Krk is currently used for open-air performances in the summer months. Some castles which were properties of the family:

-

Ruins of Tržan Castle in Modruš, once a seat of the Frankopan family on Croatian mainland

-

Drežnik Castle

-

Grobnik Castle

-

Novi Vinodolski Castle

-

Novigrad na Dobri Castle

-

Ribnik Castle

-

Slunj Castle

-

Severin na Kupi Castle

-

Stara Sušica Castle

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Obitelj Frankopani". ARHiNET (digital archive information system of Croatian State Archives). Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ a b c d e "Frankapan (Frankopan)". Croatian Biographical Lexicon (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ a b Nagy, Iván; Friebeisz, István (1858). "Frangepan csalad" [Frangepan family. In Families of Hungary. With coats of arms and genealogical plates] (PDF). Magyarország családai: Czimerekkel és nemzékrendi táblákkal (in Hungarian). Vol. 4: Ebeczky család - Gyürky család. Pest: Kiadja Friebeisz I. pp. 235–250. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-03-27. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ^ a b c d "Frankapan (Frankopan)". Croatian Encyclopedia by Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography (online edition). Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ "Frangipane, Mario". Treccani - Enciclopedia Italiana (online edition). Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ a b "Frangipane (Frangipani)". Treccani - Enciclopedia Italiana (online edition). Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ "Frankapani". Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas (online edition). Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Daniele Farlati (1775). Illyricum sacrum, vol. 5. Sebastianum Coleti. p. 640.

- ^ Flaminio Cornelio (1749). Ecclesiae Venetae (Torcellanae). Pasquali. pp. 228, 229.

- ^ Dasen Vrsalović (1968), Povijest Otoka Brača (in Croatian), Supetar, p. 70, Wikidata Q113677302

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Frankapan, Nikola IV (de Frangepan; Mikula, Nicolaus)". Croatian Biographical Lexicon by Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography (online edition). Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ a b c [Gliubich, Simeone, Dizionario biografico degli uomini illustri della Dalmazia, Vienna, 1856, p. 136.]

- ^ Petar Strčić (2002). "Vončinin genealoški, onomasiološki i kronološki pristup Franji Krsti Frankopanu". Kolo (in Croatian) (2). Matica hrvatska. ISSN 1331-0992. Archived from the original on 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- ^ "119.16 Fragiapan, Begle, Segnie et Modrusse, Niclas Comes des, Bestätigung und Erneuerung der Rotwachsfreiheit". Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (digital archive information system of National Archives of Austria. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "120.6 Frangiapan, Begle, Segnie et Modrusse, Niklas Comes de, Bestätigung und Erneuerung der Rotwachsfreiheit". Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (digital archive information system of National Archives of Austria. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Vienna, Reichsadelsakt Fragiapan, 1425, Dokument 120.6 & 119.16

- ^ a b Durbešić, Ivo pl. (2008). "Časna plemićka viška obitelj Doimi di Delupis i obmanjivači" [Honour Vis Nobility Family Doimi di Delupis and the Delusioner] (PDF). Glasnik Hrvatskog plemićkog zbora (in Croatian) (6). Hrvatski plemićki zbor: 33–43. ISSN 1845-9463.

- ^ a b c Boris Orešić (2 October 2018). "Nazivali su ga lažni plemićem, a on je tvrdio da živi samo za Hrvatsku" [They called him as a false nobleman, and he claimed to only live for Croatia: Died British entrepreneur of Croatian origin Louis Doimi de Frankopan] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Mirnik, Ivan (2004), "Luc Orešković. Les Frangipani. Un exemple de la réputation des lignages au XVIIe siècle en Europe. Cahiers Croates. Hors-serie 1, 2003. Izdanje: Almae matris croaticae alumni (A.M.C.A.). Odgovoran za publikaciju: Vlatko Marić. Mali oktav, str. 151, 33 sl., 1 genealoška shema, 7 shematskih prikaza međusobnih odnosa, tablice s opisima grbova na 7 str. ISSN nedostaje (Review article)", Historical Contributions (in Croatian), 27 (27), Croatian Institute of History: 167–179 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske

- ^ Jelena Valentić (18 March 2012). "Tajni svijet dinastije Frankopan: Dramatična istina o misterioznom međunarodnom imperiju" [The secret world of the Frankopan dynasty: A dramatic truth about a mysterious international empire] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ David Brown; et al. (30 September 2006). "Royal match that really is a fairytale". The Times.

- ^ Željko Godeč (2002-09-25). "Lažno Hrvatsko Plemstvo: Hrvatska misija lažnih Frankopana" [False Croatian nobility: Croatian mission of false Frankopans] (in Croatian). No. 352. Nacional.

- ^ "Lažna plemkinja Paula de Frankopan uskoro se udaje za lorda Windsora" [False noblewoman Paula De Frankopan will soon marry Lord Windsor] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. 30 September 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Gapper, John (April 19, 2019). "Silk Roads author Peter Frankopan: 'We're in trouble in the long term'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

This brings us to a sensitive matter. The family used the surname Doimi du Subic in his youth and his father was criticised in Croatia for later switching to Frankopan and adopting the title of prince. Frankopan looks anxious when I mention it. "People get overexited about this - It's all highly Croatian. We were given the name Frangipani by the Pope in 1425. Then in 1671, the other branch of the family had their heads cut off. We lived in Dalmatia, along the coast, minding our own business. We always had the same name

- ^ Mario Pušić (7 April 2012). "Frankopani upropastili Ribnik: 'Rekla nam je da je savjetnica pape pa smo joj dali dvorac'" [Frankopan ruined Ribnik: 'She told us that was an advisor of Pope so we gave her a castle'] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Prokletstvo dvorca Ribnik" [Curse of Castle Ribnik] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. 30 December 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "U Ribniku predstavljeni razvojni projekti, jedan od njih vezan i za dvorac – od privatnog vlasnika želi ga kupiti Karlovačka županija" [In Ribnik are presented development projects, one of them related to the castle - from a private owner wants to buy it Karlovac County] (in Croatian). KAPortal - RTL Hrvatska. 27 August 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Fontes rerum Bohemicarum III[permanent dead link]