A Frank Statement

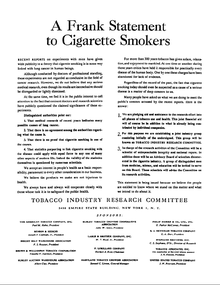

A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers was a historic first advertisement in a campaign run by major American tobacco companies on January 4, 1954, to create doubt by disputing recent scientific studies linking smoking cigarettes to lung cancer and other dangerous health effects.[1]

Reaching an estimated 43 million people through more than 400 newspapers throughout the United States, A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers and subsequent advertisements were designed by public relations firm Hill & Knowlton to socially engineer the public's perceptions of tobacco and to instill doubt about scientific research linking disease and smoking.[1][2] As a result of A Frank Statement and tobacco advertisements that still exist today, the tobacco industry continues to expand its markets by avoiding health concerns and portraying its products in a positive light.[3]

Historical context

[edit]Reports of a link between tobacco and lung cancer emerged as early as 1912, but until the 1950s, the evidence was circumstantial since smoking was so pervasive in society.[4]

In 1950, hoping to find the cause of the significant surge in lung cancer incidence in the US and England, Dr. Richard Doll and Professor Bradford Hill conducted a case-control study in which lung cancer, other cancer, and non-cancer patients from twenty London-area hospitals were interviewed about their smoking habits. The study, published in the British Medical Journal, found that the lung cancer patients were more likely to be heavier smokers than the other cancer and non-cancer control patients.[5] These results revealed to the medical community that a link between smoking and lung cancer may exist. Smoking was so prevalent that before these results were published, the increase in lung cancer incidence was attributed to the growing presence of automobiles, roads, and factories in cities.[6]

In 1950, Dr. Ernst Wynder and Evarts Ambrose Graham published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association in which they interviewed 684 people with proven cases of lung cancer about their smoking habits. The study found that heavy and sustained usage of tobacco, especially in the form of cigarettes, increased the likelihood of developing of lung cancer.[7] In 1952, to study the biological likelihood of cancer being linked to smoking, Wynder published an animal study in the US journal Cancer Research that found that tobacco tar was carcinogenic when applied to the skin of mice.[8]

The December 1952 issue of Reader's Digest featured an article, titled Cancer by the Carton, that discussed these recent studies on the link between smoking and lung cancer. The article presented to the public the studies' conclusion that tobacco causes lung cancer.[9] As a result, the article provoked a health scare, which resulted in a small drop in consumption, and a fall in stock prices.[2]

In 1954, Doll and Hill published another article in the British Medical Journal releasing the results of the British Doctors Study, which revealed a significant pattern of increased death from lung cancer as the amount of tobacco smoked increased.[10]

In the early 1950s, which were the immediate post-war years and the beginning of the nuclear age, science was very highly regarded by the public, so the accumulating scientific evidence linking tobacco to lung cancer posed a major threat to the tobacco companies' public image.[11]

Social engineering

[edit]With mounting evidence of a link between smoking tobacco and lung cancer, tobacco companies faced a dilemma of whether to admit to or deny the health risks of smoking. In order to preserve their industry, the tobacco companies opted to completely deny health risks. Instead, the tobacco companies crafted a strategy that, through creative advertising and marketing, would manipulate the cultural context surrounding their product from one that regarded the product unfavorably to one that held the product in high esteem. This strategy is known as social engineering.[11]

On December 15, 1953, led by Paul Hahn, the head of American Tobacco, the six major tobacco companies (American Tobacco Co., R. J. Reynolds, Philip Morris, Benson & Hedges, U.S. Tobacco Co., and Brown & Williamson) met with public relations company Hill & Knowlton in New York City to create an advertisement that would assuage the public's fears and create a false sense of security in order to regain the public's confidence in the tobacco industry.[12] Hill and Knowlton's president, John W. Hill, realized that simply denying the health risks would not be enough to convince the public. Instead, a more effective method would be to create a major scientific controversy in which the scientifically established link between smoking tobacco and lung cancer would appear not to be conclusively known.[13]

The tobacco companies fought against the emerging science by producing their own science, which suggested that existing science was incomplete and that the industry was not motivated by self-interest.[11] With the creation of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee, headed by accomplished scientist C.C. Little, the tobacco companies manufactured doubt and turned scientific findings into a topic of debate. The recruitment of credentialed scientists like Little who were skeptics was a crucial aspect of the tobacco companies' social engineering plan to establish credibility against anti-smoking reports. By amplifying the voices of a few skeptical scientists, the industry created an illusion that the larger scientific community had not reached a conclusive agreement on the link between smoking and cancer.[11]

Internal documents released through whistleblowers and litigation, such as the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, reveal that while advertisements like A Frank Statement made tobacco companies appear to be responsible and concerned for the health of their consumers, in reality, they were deceiving the public into believing that smoking did not have health risks. The whole project was aimed at protecting the tobacco companies' images of glamour and all-American individualism at the cost of the public's health.[14]

Claims

[edit]A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers claims:

- That medical research of recent years indicates many possible causes of lung cancer.

- That there is no agreement among the authorities regarding what the cause is.

- That there is no proof that cigarette smoking is one of the causes.

- That statistics purporting to link cigarette smoking with the disease could apply with equal force to any one of many other aspects of modern life. Indeed, the validity of the statistics themselves is questioned by numerous scientists.[1]

The claims made in A Frank Statement were largely false as:

- Recent medical research had indicated that while lung cancer does have many possible causes, smoking is by far the leading cause in many different types of cancer.[15]

- Most scientists, except for skeptics hired by the tobacco companies, agreed that cigarette smoking is linked to lung cancer incidence.[14]

- Multiple studies have shown a clear link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer.[5][7][10]

- The studies linking cigarette smoking to lung cancer controlled for the "many other aspects of modern life" to show that cigarette smoking is the main cause.[7] Many of the "numerous scientists" who questioned the validity of the statistics were under the payroll of the tobacco companies.[1][11]

Promises

[edit]The advertisement also made several promises on behalf of the tobacco industry which were later disputed by the scientific community. In A Frank Statement, the tobacco companies stated that they believed that their products were safe; however, in a 2002 assessment of the promises made by the advertisement, it was concluded that some tobacco industry scientists believed that there was a causal relationship between tobacco and cancer.[16] Research was undertaken to find a safer cigarette, but tobacco companies realized that they could not produce a safer cigarette because doing so would mean admitting that current cigarettes were not safe.[16] Thus, the industry responded to the growing public concern by marketing their cigarettes as having filters, milder smoke, and lower tar and nicotine content; however, they did not acknowledge a causal link with cancer until 1999.[16]

A Frank Statement also pledged "aid and assistance to the research effort into all phases of tobacco use and health", and announced the establishment of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC) to work towards that goal.[1] Much of the TIRC funded research was not directly connected to smoking as it focused mainly on cancer basics, such as immunology, genetics, cell biology, pharmacology, and virology, rather than cancer's connection to smoking.[11] Neither the TIRC nor its successor, the Council for Tobacco Research, ever acknowledged a proven link between smoking and serious and/or life-threatening illness. When research did find a link between smoking and cancer, however, the findings were rarely reported to the public.[16] Despite the irrelevance of much of the TIRC funded research to the health effects of smoking, the tobacco industry continued to publicize its funding of the TIRC to reassure the public.[16] In reality, the TIRC was created as a public relations measure for the purposes of discrediting independent science and portraying the tobacco companies as transparent and concerned for the well-being of their customers.[11]

Finally, the advertisement promised that the tobacco companies "always have and always will cooperate closely with those whose task it is to safeguard the public health".[1] According to Cummings, Morley, and Hyland, "there is abundant evidence that the tobacco industry went to great lengths to undermine tobacco control efforts of the public health community".[16] An example of this is a memo from the vice-president of the Tobacco Institute in which the industry's strategy was described as "creating doubt about the health charge without actually denying it", and "advocating the public's right to smoke, without actually urging them to take up the practice".[16] By proclaiming that the health risks were not conclusively linked to smoking, the tobacco companies manipulated the situation to place all liability on the consumer rather than on themselves.[11]

Impact on the public

[edit]Although the tobacco industry claims that their advertising is only used to convince current smokers to switch between brands and that it does not increase total cigarette consumption, research into the effects of advertising shows that it plays an essential role in projecting positive connotations of smoking cigarettes onto potential new smokers.[14] From 1954, when Hill & Knowlton first started working with the tobacco industry, to 1961, the number of cigarettes sold annually rose from 369 billion to 488 billion, and the annual per capita consumption rose from 3344 to 4025 cigarettes.[11]

The first cigarette advertisements claimed that smoking cigarettes had a variety of health benefits, such as prolonged youth, thinness, and attractiveness.[14] However, as more research revealed the deceptiveness of these claims, tobacco companies began to use advertisements, like A Frank Statement, to deny that their products caused cancer. Claiming that advertisement bans would infringe on "commercial free speech", the tobacco industry has continually fought against them; however, the industry has never responded to criticism that much of its advertising, like the claims made in A Frank Statement, is deceptive.[14] As a result, the tobacco industry's manipulation of science as a public relations tactic is still used today in debates on a wide variety of subjects including global warming, food, and pharmaceuticals.[17]

Modern-day examples

[edit]Today, tobacco companies continue to aggressively advertise cigarettes. As cigarette consumption has declined in the United States, tobacco companies have greatly increased their advertising expenditure. In 1991, the industry spent $4.6 billion on advertising and promoting cigarette consumption,[3] and in 2015, tobacco companies spent $8.9 billion on advertising just in the United States.[18] Tobacco companies continue to use this money to fund social engineering techniques, such as campaigns featuring themes of social desirability and specific cultural references, to target women, children, and specific racial/ethnic communities.[18] For example, to make cigarettes appealing to African American communities, the industry has implemented campaigns that use urban culture and language while sponsoring Chinese and Vietnamese New Year festivals to target Asian Americans.[18]

With declining levels of smoking in the West due to smoking bans and increased education on the health risks of smoking, tobacco companies have also expanded their market into developing countries to fulfill the industry's ever-present need for new smokers and more money. Using many of the same advertising techniques of glamour, sex, and independence, the industry has begun to target women and children in Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, where government bans and health education may not be as prevalent.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Daily Doc: The 'Frank Statement' of 1954". www.tobacco.org. November 7, 2017. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Martha, Derthick (July 26, 2011). Up in smoke: from legislation to litigation in tobacco politics (Third ed.). Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. pp. 33–41. ISBN 978-1452202235. OCLC 900540359.

- ^ a b Youths, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and; Lynch, Barbara S.; Bonnie, Richard J. (1994). Tobacco Advertising and Promotion. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ Thun, Michael J (2005). "When truth is unwelcome : the first reports on smoking and lung cancer : Public Health Classics".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ a b Doll, Richard; Hill, A. Bradford (September 30, 1950). "Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung". British Medical Journal. 2 (4682): 739–748. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4682.739. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2038856. PMID 14772469.

- ^ LaMorte, Wayne W. (October 18, 2017). "Epidemiology of Chronic Diseases". sphweb.bumc.bu.edu. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c Wynder, Ernest L.; Graham, Evarts A. (May 24, 1985). "Tobacco Smoking as a Possible Etiologic Factor in Bronchiogenic Carcinoma: A Study of Six Hundred and Eighty-Four Proved Cases". JAMA. 253 (20): 2986–2994. doi:10.1001/jama.1985.03350440064033. PMC 2623809. PMID 3889389.

- ^ Nutt, David (2012). Drugs-- without the hot air : minimising the harms of legal and illegal drugs. Cambridge, England: UIT. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-1906860165. OCLC 795182557.

- ^ Norr, Roy (December 1952). "Cancer by the Carton". legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Doll, Richard; Hill, A. Bradford (June 26, 1954). "The Mortality of Doctors in Relation to Their Smoking Habits". British Medical Journal. 1 (4877): 1451–1455. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4877.1451. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2085438. PMID 13160495.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Brandt, Allan M. (January 2012). "Inventing Conflicts of Interest: A History of Tobacco Industry Tactics". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (1): 63–71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300292. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3490543. PMID 22095331.

- ^ Goodman, Michael J. (September 18, 1994). "Tobacco's Pr Campaign : The Cigarette Papers". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ University of Bath (October 17, 2012). "Hill & Knowlton". www.TobaccoTactics.org.

- ^ a b c d e f Bates, Clive, and Andy Rowell. "Tobacco Explained" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ Wynder, Ernest L. (April 3, 1952). "Some Practical Aspects of Cancer Prevention". New England Journal of Medicine. 246 (14): 538–546. doi:10.1056/nejm195204032461405. PMID 14910855.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cummings, K. M.; Morley, C. P.; Hyland, A. (March 2002). "Failed promises of the cigarette industry and its effect on consumer misperceptions about the health risks of smoking". Tobacco Control. 11 (Suppl 1): I110–117. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i110. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 1766060. PMID 11893821.

- ^ Brownell, Kelly D.; Warner, Kenneth E. (March 2009). "The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food?". The Milbank Quarterly. 87 (1): 259–294. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. ISSN 1468-0009. PMC 2879177. PMID 19298423.

- ^ a b c Health, CDC's Office on Smoking and (November 16, 2017). "CDC - Fact Sheet - Tobacco Industry Marketing - Smoking & Tobacco Use". Smoking and Tobacco Use. Retrieved December 6, 2017.