Valerie Taylor (novelist)

Valerie Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Velma Nacella Young September 7, 1913 Aurora, Illinois, US |

| Died | October 22, 1997 (aged 84) Tucson, Arizona, US |

| Pen name | Valerie Taylor, Nacella Young, Francine Davenport |

| Occupation | Writer and activist |

| Literary movement | Lesbian pulp fiction |

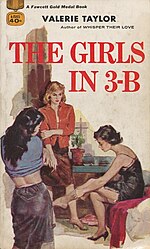

| Notable works | The Girls in 3-B (1959) |

| Partner | Pearl Hart |

Valerie Taylor (September 7, 1913 – October 22, 1997) was an American author of books published in the lesbian pulp fiction genre, as well as poetry and novels after the "golden age" of lesbian pulp fiction. She also published as Nacella Young (under which she wrote her poetry), Francine Davenport (under which she wrote her romances), and Velma Tate. Her publishers included Naiad Press, Banned Books, Universal, Gold Medal Books, Womanpress, Ace and Midwood-Tower.

Early life and education

[edit]Velma Nacella Young was born on September 7, 1913, in Aurora, Illinois, to Elsie M. Collins and Marshall J. Young. She grew up on her family's farm, with her younger sister Rose Marie and her paternal grandparents.[1] She came from a "tradition of women's activism"; one of her great-grandmothers marched in the first suffrage parade in Elgin, Illinois in 1889.[2] Additionally, many of her family members were avid readers -- "her family had little money but plenty of books."[3] Taylor also frequently and proudly referred to her Potawatomi heritage.[2]

Young graduated from Elgin High School.[4] Five years later, she was granted a two-year scholarship to Blackburn College in Carlinville, Illinois where she studied education, during the Great Depression.[5][6] There, she gained the credentials to teach at country schools, and was introduced to grassroots activism and "made her a socialist."[3] She joined the American Socialist Party at age twenty-two.[6]

Feeling that social norms compelled her to find a husband, she married William Jerry Tate in 1939, thus changing her name to Velma Tate. In the same year that they married, she had her first son, Marshall, and then two years later they had twins Jerry and Jim.[6] After fourteen years of marriage, she described how her husband had proved to be an alcoholic bum. The same year that she published her first novel, Hired Girl, which she received $500 for, she "bought a pair of shoes, two dresses, and hired a divorce lawyer."[7] In 1953, they divorced, and Velma left with her sons to “The Colony” in Chicago.[5]

Writing and activism career

[edit]Writing

[edit]She began writing while she was married to Tate to provide additional financial support to the household.[6] She was published in magazines under several pseudonyms. She also held jobs as a schoolteacher, switchboard operator, and then from 1956 to 1961, she worked in the publishing house Henry Regnery & Sons, Chicago, as assistant editor.[5]

Beacon Books published her first novel, Hired Girl (also published as The Lusty Land), in 1953. Set on a poor Midwestern farm, Hired Girl has no lesbian subject matter, but it does explore other controversial sexual and political themes. It was published under the pseudonym Valerie Taylor.[4]

From 1957 to 1967, living in Chicago, Taylor wrote novels in the genre of lesbian pulp fiction, in which she became well known under her pen-name. She explained her reasons for choosing the genre: "I began writing gay novels around 1957. There was suddenly a plethora of them on sale in drugstores and bookstores... many written by men who had never knowingly spoken to a lesbian. Wish fulfillment stuff, pure erotic daydreaming. I wanted to make some money, of course, but I also thought that we should have some stories about real people."[8]

Her first lesbian pulp novel was Whisper Their Love, published in 1957. Further classic lesbian pulps by Taylor followed, raising her penname to notoriety as one of the "pro-lesbian pulp authors".[9] In discussing her first novel, the working title of which was The Heart Takes Many Paths, the title was changed by the publisher to Whisper Their Love, which Taylor called "a disgusting title" chosen to conform to the then-common publishing industry convention of presenting lesbians as lonely women living lives of secrecy. The book, which describes a lesbian love affair, concludes with the main character forming a heterosexual relationship, which according to Lisa Walker disappointed later readers but was one of the few types of endings 1950s publishers would accept. Two years later, The Girls in 3-B was according to Walker "remarkable in providing a happy ending for the lesbian character".[6]

Writing became her career and means of supporting her sons. She published stories, reviews, and criticisms in The Ladder, and also published poetry under the pseudonym Nacella Young, and romances as Francine Davenport.[5]

Through her six popular lesbian pulps, Valerie Taylor became known for writing characters and plots which deal with the experience of life in the working class, as well as the imbalance of social and economic power between male employers and female employees.[6] Due to her notoriety in the lesbian pulp fiction genre, as well as her public activism during her time in Chicago, she was dubbed one of the "Lesbian Grandmothers of America."[2] Cornell University, which houses her literary estate, calls her novels "pulp fiction classics."[5] In the afterword to a 2003 reprint, Lisa Walker of the University of Southern Maine wrote that "The Girls in 3-B is a part of the unofficial history of women in the 1950s.[6]

She continued writing well into her 80s, covering stories of women in old age and encountering poverty. From 1977 to 1989, Naiad Press' Barbara Grier convinced Taylor to publish her new, more feminist lesbian novels with them; these novels were Love Image, Prism, and Rice and Beans, in addition to republishing older lesbian pulps.[4]

In 1975, she received the Paul R. Goldman award from the Chicago Chapter of One, Inc. In 1992, she was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame.[5]

Activism

[edit]She was prominent in activist causes from the 1950s through the 1980s, including LGBT rights, feminism, and Elder rights. She belonged to the Daughters of Bilitis, contributing her work to their magazine The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication. Taylor was instrumental in starting the gay and lesbian advocacy group Mattachine Midwest along with Pearl Hart in 1965. She lent her services to its newsletter as editor for several years.[6] She protested at the 1968 Democratic Convention with other members of Mattachine Midwest, and she worked with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

Young was also a member of the Gray Panthers, a social justice activist group. Additionally, she became involved in activism in the environmental movement and advocacy for the elderly.[10]

Along with others, Young helped to found the Lesbian Writers Conference in Chicago in 1974, and was a keynote speaker at the event. She dedicated the inaugural conference to her friend, the pioneering librarian and researcher in the field of lesbian literature Jeanette Howard Foster.

Personal life and death

[edit]Young described herself as both bisexual and a lesbian and did not see the two as mutually exclusive. She says she realized the full extent of her attraction to women in her mid-thirties.[citation needed]

In 1965 she met Pearl Hart, another founder of Mattachine Midwest and a Chicago feminist lawyer. They were romantic partners until 1975, when Hart died. Young says she was the love of her life. Not being seen as an immediate family member, Taylor was not allowed to visit Hart in the hospital as she was dying and missed being able to tell her goodbye. She had to appeal to a friend of Hart's, but by the time she was able to see her, Hart was in a coma.[11]

In 1978 she moved to Tucson, Arizona and became a Quaker in 1979. Her health and stability began to decline in 1993 until her death on October 22, 1997, at the age of 84 in her home in Tucson, Arizona.[12] Upon her death, her work was placed in the Cornell Library's Human Sexuality Collection by Tee Corinne, the executor of her literary estate.[5] Her name was added post mortem to a lengthy list of other members of the LGBTQ community at the Tucson Gay Museum.[13]

Works

[edit]

Fiction

[edit]- The Lusty Land (originally published as Hired Girl) 1953, Universal[6]

- Whisper Their Love 1957, Gold Medal[6]

- The Girls in 3-B 1959, Gold Medal[6]

- Stranger on Lesbos 1960, Gold Medal[6]

- A World Without Men 1963, Midwood Tower[6]

- Unlike Others 1963, Midwood Tower[6]

- Return to Lesbos 1963[6]

- Journey to Fulfillment 1964, Midwood Tower[6]

- The Secret of the Bayou 1967, Ace (as Francine Davenport)

- Unlike Others 1976, Midwood

- Love Image 1977, Naiad[6]

- Prism 1981, Naiad[6] with Tee Corinne

- Ripening 1988, Banned Books

- Rice and Beans 1989[6]

Poetry

[edit]- Two Women: The Poetry of Jeannette Foster and Valerie Taylor 1976, Womanpress[6]

- The Rooted Heart, Prairie Schooner (as Nacella Young)

- Sonnet for a Second Love, The Georgia Review (as Nacella Young)

References

[edit]- ^ "Velma L Young" in the 1920 United States Federal Census (Year: 1920; Census Place: Greenfield, LaGrange, Indiana; Roll: T625_443; Page: 6B; Enumeration District: 122)

- ^ a b c "VALERIE TAYLOR – Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ^ a b D'Emilio, John (2014). In a New Century: Essays on Queer History, Politics, and Community Life. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 152.

- ^ a b c Baim, Tracy; Harper, Jorjet (2009). Out and Proud in Chicago: An Overview of the City's Gay Community. Agate Publishing. p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Human Sexuality Collection: Valerie Taylor Papers". Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Walker, Lisa (2003). Afterword. The girls in 3-B. By Taylor, Valerie (1st Feminist Press ed.). New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York. ISBN 1-55861-462-1. OCLC 52478429.

- ^ "Valerie Taylor". Feminist Press. 16 October 2016. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ In: Keller, Yvonne. "Was it Right to Love Her Brother's Wife So Passionately? Lesbian Pulp Novels and U.S. Lesbian Identity, 1950–1965." American Quarterly, 2005

- ^ "Young, Velma (Valerie Taylor)". msvulpf.omeka.net. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ "Cornell Library Opens the Papers of Lesbian Writer Valerie Taylor | Rare and Manuscript Collections". rare.library.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ^ Kuda, Marie. "Valerie Taylor." Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History in America. Charles Scribner & Sons, 2004.

- ^ "Tucson, AZ Obituary Valerie Taylor Author and Poet". Arizona Daily Star. November 7, 1997. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Tucson Gay Museum Special Exhibits 'Memorium Wall' Is A Place To Remember Those LGBTQ Brothers and Sisters Who Have Come Before Seeking Their Basic Equality And Civil Rights For All LGBTQ People, Recognition As Valuable And Productive Citizens, And Along The Way Spreading The Colors Of The Rainbow To The Many They Came In Contact With..." www.tucsongaymuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

Further reading

[edit]- Valerie Taylor Collection at Cornell University: Cornell University

- GLBTQ: The history of gay and lesbian romance novels: GLBTQ

- 1913 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people

- 20th-century American writers

- 20th-century American women writers

- 20th-century Quakers

- American bisexual writers

- American elder rights activists

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- American Quakers

- American people who self-identify as being of Potawatomi descent

- American socialist feminists

- American socialists

- American women poets

- Bisexual women writers

- Converts to Quakerism

- LGBTQ Quakers

- LGBTQ people from Illinois

- Potawatomi people

- Pulp fiction writers

- Quaker feminists

- Women's International League for Peace and Freedom people

- Writers from Illinois