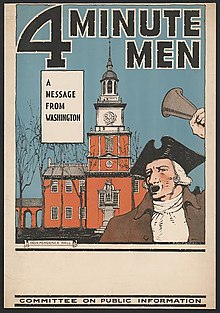

Four Minute Men

The Four Minute Men were a group of volunteers authorized by United States President Woodrow Wilson to give four-minute speeches on topics given to them by the Committee on Public Information (CPI). In 1917–1918, over 750,000 speeches were given in 5,200 communities by over 75,000 accomplished orators, reaching about 400 million listeners.[1] The topics dealt with the American war effort in the First World War and were presented during the four minutes between reels changing in movie theaters across the country. The speeches were made to be four minutes so that they could be given at town meetings, restaurants, and other places that had an audience.

History

[edit]On April 6, 1917, the US Congress declared war on Germany. President Wilson was determined to rouse the public.

Wilson established the first modern propaganda office, the Committee on Public Information (CPI), headed by George Creel.[2][3] Creel set out to systematically reach every person in the United States multiple times with patriotic information about how the individual could contribute to the war effort. The CPI also worked with the post office to censor seditious counter-propaganda. Creel set up divisions in his new agency to produce and distribute innumerable copies of pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men. The CPI created colorful posters that appeared in every store window, catching the attention of the passersby for a few seconds.[4] Movie theaters were widely attended, and the CPI trained thousands of volunteer speakers to make patriotic appeals during the four-minute breaks needed to change reels. They also spoke at churches, lodges, fraternal organizations, labor unions, and even logging camps.

CPI Director George Creel boasted that in 18 months his 75,000 volunteers delivered over 7.5 million four-minute orations to over 300 million listeners, in a nation of 103 million people. The speakers attended training sessions through local universities, and were given pamphlets and speaking tips on a wide variety of topics, such as buying Liberty Bonds, registering for the draft, rationing food, recruiting unskilled workers for munitions jobs, and supporting Red Cross programs. Ethnic groups were reached in their languages.[5][6]

Purpose

[edit]With many millions of German Americans, Irish Americans and Scandinavian Americans in the United States, and poor rural Southerners with strong isolationist feelings, there was a strong need for a propaganda campaign to stir support for the war. This effort had many unique challenges to meet to address the existing political climate. Wilson needed to speak directly to the fragmented and spread out audience in the United States. He had to address the country's self-perception to generate support for the war. The Four Minute Men provided an answer to these challenges.[7]

In addition, the Four Minute Men urged citizens to purchase Liberty Bonds and Thrift Stamps.[8][9][10]

Addressing challenges

[edit]The Four Minute Men idea became a useful tool in the propaganda campaign because it addressed a specific rhetorical situation. One of the challenges of the effort was the fragmented audiences of the United States. Many different heritages were represented in the country, and President Wilson needed their support for the war. To address each group's specific needs, the director of the Four Minute Men, William McCormick Blair, delegated the duty of speaking to local men. Well known and respected community figures often volunteered for the Four Minute Men program. This gave the speeches a local voice. The Four Minute Men were given general topics and talking points to follow and rotated between theaters to help the speeches seem fresh, instead of generic propaganda.

The speeches usually depicted Woodrow Wilson as a larger-than-life character and the Germans as less-than-human Huns.[11]

Organization

[edit]The Four Minute Men were a division of the Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel. The Committee on Public Information appointed William McCormick Blair as director of the Four Minute Men. Blair appointed state chairmen of the Four Minute Men, who then would appoint a city or community chairman. Each of these appointments needed to be approved in Washington. The local chairman would then appoint a number of speakers to cover the theaters in the city or community for which he is responsible.

Notable Four Minute Men

[edit]- Charles Chaplin, a famous comedian

- Douglas Fairbanks[12]

- Louis Webster Gerhardt, attorney, Hazelton, Pennsylvania

- Alfred Gilbert,[13] an inventor, athlete, magician, toy-maker and businessman

- Lambert Estes Gwinn, Four Minute Man from Covington, Tennessee

- William S. Hart[12]

- Benjamin Newhall Johnson, Four Minute Man from Lynn, Massachusetts

- Albert Dutton MacDade, Pennsylvania State Senator and Judge Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas (Delaware County)

- DeForest H. Perkins, School Superintendent and future Grand Dragon of the Maine Ku Klux Klan

- Mary Pickford[12]

- Augustus Post, automotive pioneer, founder of American Automobile Association, champion balloonist and early aviator

- Phebe Temperance Sutliff, president, Rockford College

- Ellwood J. Turner, Pennsylvania State Representative from Delaware County (1925–1948), 119th Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives (1939–1941)

- Otto J. Zahn, a Southern California Four Minute Man

- John Rustgard

References

[edit]- ^ "Four Minute Men | Surveillance and Censorship | Over Here | Explore | Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I | Exhibitions at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

- ^ George Creel, How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe (1920).

- ^ Stephen Vaughn, Holding Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information (1980). online Archived 2019-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Katherine H. Adams, Progressive Politics and the Training of America’s Persuaders (1999).

- ^ Lisa Mastrangelo, "World War I, public intellectuals, and the Four Minute Men: Convergent ideals of public speaking and civic participation". Rhetoric & Public Affairs 12#4 (2009): 607-633.

- ^ Committee on public information, Complete Report of the Committee on Public Information: 1917, 1918, 1919 (1920)

- ^ Lisa Mastrangelo, "World War I, public intellectuals, and the Four Minute Men: Convergent ideals of public speaking and civic participation." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 12#4 (2009): 607-633.

- ^ The American Year Book: A Record of Events and Progress, Volume 1918. T. Nelson & Sons. 1919.

- ^ Stone, Oliver; Kuznick, Peter (2014). The Untold History of the United States, Volume 1: Young Readers Edition, 1898-1945. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781481421751.

- ^ The Four Minute Men of Chicago. Chicago, Illinois: United States Committee on Public Information. 1919. p. 25.

- ^ Goldberg, Jonah (2009). Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, from Mussolini to the Politics of Change. Crown Publishing. ISBN 978-0767917186.

- ^ a b c philadelphia in the world war 1914-1919. The Philadelphia War History Committee. 1922. p. 495.

- ^ Watson, Bruce (2002). The Man who Changed how Boys and Toys Were Made. Viking Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0670031344.

- Bibliography

- Cornebise, Alfred E. War as Advertised: the Four Minute Men and America's crusade, 1917-1918. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1984. ISBN 0871691566 OCLC 11222054

- Cornwell, Elmer E. Jr. "Wilson, Creel, and the Presidency." The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol 23, No. 2, pages 189–202. ISSN 0033-362X

- Creel, George. "Propaganda and Morale". The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 47, No. 3. (Nov., 1941), pages 340–351. ISSN 0002-9602

- Creel, George. How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe Corner (1920)

- Larson, Cedric, and James R. Mock. "The Lost Files of the Creel Committee". The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 1. (Jan., 1939), pages 5–29. ISSN 0033-362X

- Larson, Cedric, and James R. Mock. "The Four-Minute Men." The Quarterly Journal of Speech: 97–112. ISSN 0033-5630

- Mastrangelo, Lisa. "World War I, public intellectuals, and the Four Minute Men: Convergent ideals of public speaking and civic participation." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 12#4 (2009): 607–633.

- Oukrop, Carol. "The Four Minute Men Became National Network During World War I." Journalism Quarterly: 632–637. ISSN 0196-3031

- Vaughn, Stephen L. Holding Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information (2nd ed. 2011), a standard scholarly history

Primary sources

[edit]- Committee on public information, Complete Report of the Committee on Public Information: 1917, 1918, 1919 (1920) online free

Further reading

[edit]- John Maxwell Hamilton, Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda [1]