History of Georgetown University

The history of Georgetown University spans nearly 400 years, from the early European settlement of America to the present day. Georgetown University has grown with both its city, Washington, D.C., and the United States, each of which date their founding to the period from 1788 to 1790. Georgetown's origins are in the establishment of the Maryland colony in the seventeenth century. Bishop John Carroll established the school at its present location by the Potomac River after the American Revolution allowed for free religious practice.

The role of the Society of Jesus in the school's operation has evolved from that of founders and financiers to faculty and advisers. Their focus on liberal studies and religious pluralism have helped to give the school its identity. Georgetown was also affected by its times, including the American Civil War, which disrupted the growing school and significantly changed its student body. University presidents like Patrick Francis Healy modernized the institution into an active research university with several graduate and undergraduate schools, and oversaw the expansion of educational opportunities on campus, around the city, and abroad.

Founding

[edit]

The history of Georgetown University traces back to two formative events, in 1634 and 1789. Until 1851, the school used 1788, the start of construction on the Old South building, as its founding date. In that year a copy-edit in the college catalog began mislabeling the construction as beginning in 1789. This was discovered in preparation for the centennial celebration in 1889, at which point, rather than correct the annual, the date of Georgetown's foundation was fixed to the date January 23, 1789.[3]

First establishments

[edit]On November 22, 1633 Jesuits Andrew White, John Altham Gravenor, and Thomas Gervase set sail on The Ark for English America under the leadership and financing of the Lord Baltimore, Leonard Calvert.[4] Their landing on March 25, 1634, on St. Clement's Island marks the birth of the Maryland colony, this anniversary now celebrated as Maryland Day. These Jesuits were joined in 1637 by Thomas Copley and Ferdinand Poulton, and together established a missionary fort next to a series of native dwellings near St. Mary's City on land purchased from the local Yaocomico tribe, which they paid for with hatchets, axes, hoes, and cloth.[5][6]

Inquiring about patronage for a school at this site, Poulton wrote to Vincenzo Carafa, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus in Rome under Pope Urban VIII, who on September 15, 1640, approved the institution of a school in principle.[7] That year they moved to a permanent building at Calverton Manor on in the Wicomico River. This early establishment was burnt in 1645 as part of the English Civil War, and the remaining Jesuits were brought to trial by the Crown. The new Protestant administration had their school outlawed, though it was functioning by 1648, when Thomas Copley managed to return there.[6]

Newtown Manor, also known as "Bretton's Neck", near modern-day Leonardtown, Maryland, become available to the Jesuits in 1677. This house served as the Jesuit schoolhouse until 1704 when its existence was alerted to the colonial authorities. The school afterward conducted itself periodically and in secrecy at the new Jesuit colony of Bohemia Manor. Bishop John Carroll attended this school from 1745 until 1748.[8] Carroll then left for studies in Europe. He joined the Jesuits in 1753, and was ordained in 1769, but in 1774 Pope Clement XIV ordered the suppression of the Jesuit order, forcing Carroll to return to Maryland.[9] This put Carroll in the right place at the right time, when the American Revolution pushed out the British administration, opening up new possibilities for scholastic expansion.[citation needed]

Georgetown Heights

[edit]

After returning in 1774 to live on the Rock Creek in Maryland, Carroll established Saint John the Evangelist Church, in Silver Spring, Maryland. In 1776, his cousin, Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, invited John to join him, Samuel Chase, and Benjamin Franklin in traveling to Quebec and attempt to persuade the French Canadian population to join the revolution. The mission was unsuccessful, but John Carroll's association with Benjamin Franklin proved useful. In 1784, Franklin, as ambassador to France, recommended Carroll to the papal nuncio in Paris as the head of the Catholic Church in America, and on June 9, 1784, Carroll was anointed Superior of Missions in the United States of North America. On November 6, 1789, Carroll's authority was confirmed after being elected by the clergy as the first Bishop of Baltimore.[10]

Beginning in 1783, Carroll convened meetings of area clergy, mostly ex-Jesuits, at Sacred Heart Church at White Marsh Manor, outside Annapolis, Maryland. This body, known as the General Chapters, resolved on November 13, 1786, that "a school be erected for the education of youth" and that the location for the school would be in Georgetown.[11][12] The site was influenced by Carroll's experience with Jesuit colleges in Europe, which were located in urban centers.[13] Port towns were used by Jesuits because of their missionary focus. By March 1787, they formed a fund raising committee, and Carroll solicited formal proposals for an "academy, at George-town, Patowmack-River, Maryland."[14] The District of Columbia's borders wouldn't be defined until the passage and implementation of the Residence Act in 1790.[15]

Georgetown Academy

[edit]On April 24, 1787, Georgetown landowner John Threlkeld donated a plot of land to Carroll, which was ultimately where he founded Holy Trinity Church.[16] In April 1788, construction began at a larger neighboring plot on Georgetown's first building, later called "Old South", leading Carroll to write "We shall begin the building of our Academy this summer. On this Academy are built all my hopes of permanency and success of our holy religion in the United States."[17] On January 23, 1789, John Carroll, Robert Molyneux and John Ashton completed the purchase from Threlkeld and William Deakins, Jr. for "seventy five pounds current money" of the acre and a half on which construction had already started.[14] This land became the core of Georgetown's campus. As a result, the university celebrates this date as its founding.[18]

Carroll had difficulty filling the position of president of the Academy, with many candidates declining the job before Robert Plunkett first took the office in 1791, though he only served 18 months. He oversaw the division of the Academy into "college", "preparatory", and "elementary", with the youngest starting at age eight. Jean-Edouard de Mondésir became the first teacher in late October 1791, and the first student, William Gaston, was enrolled on November 22, 1791.[19] Classes commenced on January 2, 1792, with around 69 students attending in its first year.[20] Georgetown's second building, Old North, which survives to this day, began construction in 1794. At three times the size of Old South, it greatly increased the number of classrooms and sleeping space on campus.[21] Upon the building's completion under President Rev. William Matthews, George Washington visited and spoke from the porch, a position since reserved for U.S. Presidents.

Early growth

[edit]

In its early years, Georgetown suffered from considerable financial strain, relying on private sources of funding and the limited profits from local plantations had been donated to the Jesuits by wealthy landowners.[22] Some of these included enslaved African-American workers.[23] By September 1792, tuition had to be increased for the first time.[14]

In 1796, Louis William Valentine DuBourg arrived and became president. DuBourg brought with him a collection of books from his own collection and others from St. Mary's Seminary, the Baltimore Society of Saint-Sulpice, and these books formed the nucleus of Georgetown's library.[24] On January 1, 1798, DuBourg released the first prospectus to advertise the college abroad, but also drove the school into debt by hiring numerous new faculty, including fencing teachers, and by buying silver and a school piano.[25] The first board of directors organized in 1797, and quickly became unhappy about DuBourg's spending and preference for French faculty, particularly during the Quasi-War. The board forced him to resign in December 1798.[26]

Beginning in 1798, Leonard Neale and his brother Francis oversaw the growth of the university as presidents for a combined eleven years. At Carroll's request, Neale was also appointed coadjutor bishop by Pope Pius VI in 1800. In 1799 Neale invited three sisters of the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary to open a monastery at Georgetown. On June 24, 1799, the young Georgetown Visitation Monastery under Mother Teresa Lalor began a Saturday school for young women.[27] This developed into an academy, now Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School, in 1802. Leonard Neale served as president of Georgetown until 1806, when he was succeeded by Robert Molyneux, who died in 1808. Leonard Neale's brother, Francis Neale, became president of Georgetown College in 1809.[28]

When the suppression of the Society of Jesus in Maryland ended in 1805, several former Jesuits rejoined, including Leonard Neale. Carroll commenced a series of agreements to ensure Jesuit involvement in the school. Carroll, however, never rejoined the society. In 1806 the school began a novitiate for Jesuit recruits moving from Russia, which had harbored the society during the suppression.[29]

Carroll did not seek civil recognition for Georgetown after the suppression of the international society ended in 1814. Instead of a state charter, he went to the federal government, then directly in charge of the District of Columbia. William Gaston, then a Congressman, sponsored the legislation for a congressional charter, which passed the Thirteenth Congress. Georgetown received the first federal university charter on March 1, 1815, signed into law by President James Madison.[30] This allowed Georgetown to grant academic degrees, and the college's first two recipients, a pair of brothers from New York City named Charles and George Dinnies, were awarded the degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1817.[30] Graduate degrees were first awarded in 1821,[14] and other Jesuit schools conferred degrees under Georgetown's charter for many years afterward.[31] In 1833, the Holy See empowered Georgetown to confer degrees in philosophy and theology.[32]

Founder John Carroll died December 3, 1815, at age 80, and in his will he left Georgetown $400.00, which marked the beginning of Georgetown's endowment.[24] In 1830, construction of an infirmary in the new Gervase Building brought the first hospital beds to Georgetown.

In 1838, the Maryland Jesuits sold 272 slaves from a Jesuit-owned tobacco plantation in Maryland to a plantation in Maringouin, Louisiana; a small portion of the funds from that sale were used to repay debts from recent college expansion.[23][33] Upon completion of the sale, the Maryland Jesuits ended their time as slaveholders.[34] One of the organizers, a former president of the university, Thomas Mulledy was later disciplined in Rome by the Society of Jesus for ignoring their order to keep families of slaves intact in any sale.[35] The slaves were shipped to the Deep South in the domestic slave trade, sold primarily to two sugar cane plantations.[36] Some of the money was used to found two Catholic high schools in New York City and Philadelphia, as the Jesuits believed there was a demand for urban ministry to serve the increasing number of immigrants from Europe, including Catholics from Ireland.[37]

On June 10, 1844, the growing school was reincorporated by Congress under the name The President and Directors of Georgetown College. Georgetown's Observatory, completed in 1844, was used in 1846 to determine the latitude and longitude of Washington, D.C., which was the first such calculation for the nation's capital.[32] In 1849, four Catholic doctors frustrated with what they felt were discriminatory practices at neighboring Columbian College petitioned Georgetown President James Ryder to found a medical program.[38] A building for this purpose was purchased at 12th and F Streets, and the School of Medicine was founded in 1850, holding its first classes the following year.[39]

Early student life

[edit]

From its beginning, Georgetown was not intended to be exclusively Catholic, and over its first ten years, nearly one-fifth of students were Protestant. A fifth of students were also from the Caribbean. By 1830, Jewish students were known to be attending. European immigrants and Napoleonic War refugees also made up significant parts of the early student body.[9] School rules were harshly enforced. Leonard Neale, a strict moralist, regulated students' movements such that founder John Carrol accused him of running Georgetown "on the principles of a convent."[25] There were three student organized rebellions against the Georgetown administration in the antebellum period. The most notable of these occurred in January 1850, against the administration of James A. Ryder over the school food. Students damaged the dormitories and took charge of a local hotel.[40]

The first student society, the Sodality of Our Lady, was founded in 1810 as a religious devotional group.[41] A strict revision of school rules in 1829 forbade personal conversations or particular associations.[25] Despite this the Philodemic Society was founded in 1830 as the school's debating and literary society, the oldest of its kind in America and the oldest secular group at Georgetown. Other debating societies were founded in its model, or in opposition to it in later years, such as the short lived Philisorian Society and the Philonomosian Society, which lasted from 1839 until 1935.[24][42] The College Cadets were officially organized in 1836, becoming the oldest military unit native to the District of Columbia.[43] The Dramatic Association of Georgetown College, renamed the Mask and Bauble Dramatic Society after World War I, was founded in 1852, and is itself the oldest surviving student dramatic society in America.[44][45] The first Christmas tree was introduced to campus in December 1857.[46]

Civil War

[edit]

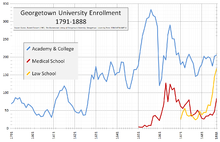

The Civil War was an important and tragic time for the university. Beginning on December 11, 1859, the Philodemic Society debated whether or not the southern states should secede. The debate lasted weeks, and after the society affirmed secession, a brawl ensued, and debates were canceled for the rest of 1860.[47] Fist fights on campus between northern and southern students soon became common. Beginning in 1861, many students left their studies to join the war. 925 students ultimately enlisted with the Confederate Army and 216 with the Union Army; between them 106 died in the war. Enrollment dropped from 313 students in 1859 to only 17 late in 1861.[9] By 1862, Georgetown only had 120 total students, about ten percent of what it was just a few years earlier.[48] Only seven students graduated in 1869, down from over 300 a decade prior.

Responding to lack of adequate hospital beds and housing for soldiers needed to protect the District, the Union commandeered University buildings, and by the time of President Abraham Lincoln's May 1861 visit to campus, 1,400 Union Army troops were stationed in temporary quarters there.[49] Of these 1,300 were from the 69th Infantry Regiment, which established itself in Maguire Hall from May 4, 1861, to June when the unit was replaced by the 79th New York Volunteer Infantry. The occupation ended in July when the unit left to fight in the First Battle of Bull Run, but the university remained home to soldiers as an infirmary for the remainder of the war.[47]

Georgetown would later be connected to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Several of John Wilkes Booth's conspirators had associations to Georgetown: David Herold, who accompanied Booth in his escape, attended the school between 1855 and 1858 and received a certificate in pharmacology in 1860, while Samuel Arnold, who conspired with Booth to kidnap Lincoln, attended in the mid-1840s, and Dr. Samuel Mudd, who set Booth's broken ankle following the assassination, studied medicine between 1851 and 1854.[50] Charles H. Liebermann, one of the founders of the medical school, was among the doctors who treated Lincoln the night he died.[51]

The years after the war drastically changed Georgetown College, making it both more northern and more Catholic.[9] Increasingly larger percentages of the student body came from northern cities, and were Catholic immigrants or their descendants. Before the war, the student body had been primarily Southern and Protestant.[14] This dynamic is expressed in Georgetown's official school colors. In 1876, Georgetown College Boat Club, the school's rowing team, adopted colors symbolizing changed times: blue, from the uniform of the Union Army, and gray, from the uniforms of the Confederate States military forces, as their team colors in order to signify the peaceful unity between students from the North and those from the South. Students at Georgetown Visitation wove the first blue and gray uniforms for the team.[52] Georgetown's motto Utraque Unum, "both into one", though used before the war, helped capture the postwar unity spirit.[53]

Expansion

[edit]

In 1874, Patrick Francis Healy became president of Georgetown University. He is now known as the first African-American president of a predominantly white university, but at the time he was generally taken to be Irish American (his father was from Ireland and he had been educated in largely white institutions, including Boston College and in France).[54] Healy's influence on Georgetown was so far-reaching that he is often referred to as the school's "second founder". He modernized the curriculum by requiring courses in the sciences, particularly chemistry and physics. Healy and his successors sought to bind the professional schools into a university, and concentrate on higher education.[9] The most visible result of Healy's presidency was the construction of a large building begun in 1877 and first used in 1881, later named Healy Hall in his honor.

A school of law was approved by the board of directors in March 1870, and graduated its first students in 1872.[55] In 1884 the "Law Department" moved to 6th and F Streets, N.W., not far from the Medical School, and then again in 1891 to 506 E Street, N.W.[56] In 1870, Georgetown raised the raise the minimum age of enrollment at Georgetown Preparatory School from eight to twelve. This was raised again in 1894 to thirteen. As part of the focus on higher education, Georgetown Preparatory School relocated from campus in 1919 to nearby North Bethesda, Maryland. It fully separated from the university in 1927.[57] Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School has remained attached to the university campus, and while independently run, the two occasionally share facilities.

Numerous new schools were founded during the twentieth century. The School of Foreign Service (SFS) was founded in 1919 by Edmund A. Walsh to prepare students for leadership in foreign commerce and diplomacy.[9] Its creation was inspired by the French grande école Sciences Po.[58] Following World War I, the U.S. Army created the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) and the Georgetown Corps of Cadets was reorganized into the Hoya Battalion.[43] The Institute of Languages and Linguistics (ILL - later renamed School of Languages and Linguistics - SLL) was organized in 1949[59] and the School of Business was created out of the SFS in 1957.[citation needed] New developments also came to School of Medicine. In 1898, Georgetown University Hospital was first established on campus. Georgetown obtained the Washington Dental College in 1901, and integrated it with the medical school.[9] In 1903, Georgetown University began an undergraduate medical program with the School of Nursing. A new Medical-Dental Building on Reservoir Road was completed in 1930 and classes then moved to the main campus. In 1951 the School of Dentistry separated from the School of Medicine as an independent unit of Georgetown University.[60]

On October 4, 1966, Congress passed a bill that recognized the school's name as "Georgetown University" for the first time.[14] The 1844 bill in effect until then had referred only to "Georgetown College", which at that point was known as the College of Arts and Sciences and was just one branch of the university. In 1970 Lauinger Library was also completed, bringing space for a rapidly growing library collection.[24] In 1971, following the completion of the Bernard P. McDonough Hall, the law school moved to its present location at 1st and F Streets at 600 New Jersey Avenue.

Across borders

[edit]

The 1950s and 60s saw major changes in administration as well as in the student body.[61] Female students have been admitted to the School of Medicine since 1880, to the School of Nursing since its founding, to the Graduate School since 1943,[62] and to the School of Foreign Service since 1944.[63] While most of the university was made available to women on a limited basis by 1952, it wasn't until the College of Arts and Sciences welcomed its first female students in the 1969–1970 academic year that Georgetown became fully coeducational.[64][65]

President Lawrence C. Gorman phased out racial segregation, with Samuel Halsey Jr. becoming the first Black undergraduate in 1950.[66] The Black Student Alliance was formed in 1968, and in 1969 Georgetown named the first Black member of the board of directors since Patrick Francis Healy.[67][68]

Freshmen hazing rituals, long tolerated by the administration, were banned in 1962 after one student brought suit against the school for injuries he sustained.[69]

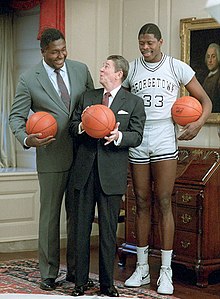

Modern Georgetown is largely a product of substantial changes during the 1980s.[70] In 1982, the School of Foreign Service moved into its new home in the Edward B. Bunn S.J. Intercultural Center.[71] The 1984 NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament championship by Georgetown's men's basketball team helped make Georgetown University a household name with stars such as Patrick Ewing and Dikembe Mutombo under Coach John Thompson. Georgetown ended its bicentennial year of 1989 by electing Leo J. O'Donovan as president. He subsequently launched the Third Century Campaign to build the school's endowment.[72] In December 2003, Georgetown completed the campaign, joining twenty other universities worldwide to raise at least $1 billion in a single fund drive. The campaign supported financial aid, academic chair endowment, and new capital projects.[73]

In 1987, the university decided to close the School of Dentistry following the class of 1990 for financial reasons, as the number of dental students dropped nationwide.[74] Supplies and equipment from the school were sent to Pontifical Xavierian University in Bogotá, Colombia.[75] In 1994, the School of Languages and Linguistics was folded into the college, and is now the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics. On October 7, 1998, the School of Business was renamed the McDonough School of Business in honor of alumnus Robert Emmett McDonough and in 2009, it moved into the newly constructed Rafik B. Hariri Building.[76] In 1999 the School of Nursing added three other health related majors and appended its name to become the School of Nursing and Health Studies.[77]

John J. DeGioia, Georgetown's first lay president, led the school from 2001 to 2024. DeGioia continued its financial modernization and sought to "expand opportunities for intercultural and interreligious dialogue."[78] In October 2002, Georgetown University began studying the feasibility of opening a campus of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service in Qatar, when the non-profit Qatar Foundation first proposed the idea. The School of Foreign Service in Qatar opened in 2005 along with four other U.S. universities in the Education City development. That same year, Georgetown began hosting a two-week workshop at Fudan University's School of International Relations and Public Affairs in Shanghai, China. This later developed into a more formal connection when Georgetown opened a liaison office at Fudan on January 12, 2008, to further collaboration.[79]

DeGioia also founded the annual Building Bridges Seminar in 2001, which brings global religious leaders together, and is part Georgetown's effort to promote religious pluralism.[80] In 1974, Woodstock College was refounded as the Woodstock Theological Center on Georgetown's campus. The Center for Contemporary Arab Studies was opened on September 3, 1975, with grants from Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Mobil Oil.[81] In 1993 the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding was opened and after a $20 million grant from Saudi Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal in 2005, the center was renamed the "Prince Alwaleed Center for Muslim–Christian Understanding".[82] The Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs was begun as an initiative in 2004, and after a grant from William R. Berkley, was launched as an independent organization in 2006.[80] Additionally, The Center for International and Regional Studies opened in 2005 at the new Qatar campus.[83]

Fictional depictions

[edit]

Georgetown, as a major world university, has been featured in many media over the years. The most prominent example is the 1971 horror novel, The Exorcist, written by William Peter Blatty, who received an English degree from Georgetown in 1950. The novel is loosely based on a series of 1949 exorcisms conducted on a fourteen-year-old boy at Georgetown University Hospital, nearby Maryland, and in St. Louis, Missouri. In 1973, Blatty's bestselling novel was made into a film, also titled The Exorcist. Like the novel, the film was set at Georgetown and filmed on campus during the fall semester in 1972.[84] The climactic scene uses a steep staircase between Prospect Street and Canal Road, previously know popularly as the "Hitchcock Steps" for their spooky appeal. However, since the film's release they have been called the "Exorcist steps".[85]

The 1985 "Brat Pack" film St. Elmo's Fire also revolved around a group of students who had just graduated from Georgetown. The bar that much of the film takes place in is based on The Tombs, a bar and restaurant known for its large student clientele and rowing decòr, located one block from Georgetown's front gates in a historic university owned house.[86] Georgetown denied the producers the rights to film on campus, so parts of the film were shot at the nearby University of Maryland, College Park.[87] Additionally, Georgetown University has been a destination for characters in films such as Above the Rim, Save the Last Dance, Election, and The Girl Next Door, as well as television shows such as The Sopranos and The West Wing, which also filmed scenes on campus.[88] The film Memento was written by Jonathan Nolan, a Georgetown alumnus, and the main character's nemesis, John G., is said to be named after John Glavin, a full professor of Victorian literature and screenwriting in Georgetown's Department of English.[89][90]

See also

[edit]- Georgetown Preparatory School

- History of Washington, D.C.

- List of presidents of Georgetown University

- List of Georgetown University alumni

- 1838 Jesuit slave sale

References

[edit]- ^ "The Georgetown Seal". Georgetown University. February 18, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ "Main entrance to the White-Gravenor Building at Georgetown University". Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 7

- ^ Nevils 1934, pp. 1–25

- ^ Ruane, Michael E. (March 22, 2021). "Archaeologists find earliest colonial site in Maryland after nearly 90-year search". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Spillane, Edward P. (1909). "Philip Fisher". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ Burns 1908, p. 90

- ^ "The Bohemia Manor Academy". Retrieved March 6, 2007. Bicentennial Exhibit

- ^ a b c d e f g Curran, Robert Emmett (July 7, 2007). "Georgetown: A Brief History". Georgetown University. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2007. Undergraduate Bulletin

- ^ "Most Rev. John Carroll". Archdiocese of Baltimore. 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ Easby-Smith 1907, pp. 22–24

- ^ "Parish History". Sacred Heart Church. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f "A Georgetown time-line". November 11, 2000. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2007. Georgetown University Libraries Special Collections

- ^ "Residence Act". Library of Congress. January 7, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Warner 1994, pp. 3–5

- ^ "The first University building". Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

- ^ "About Georgetown". Georgetown University. 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ "William Gaston and Georgetown". November 11, 2000. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2007. Bicentennial Exhibit

- ^ Curran 1993, pp. 33–34, 397

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, pp. 13–14

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 12

- ^ a b Swarns, Rachel L. (April 16, 2016). "Georgetown Faces Its Role in the Slave Trade and the Task of Making Amends". The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Special Collections at Georgetown: A Brief History". November 11, 2000. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2007. Georgetown Universities Libraries Special Collections

- ^ a b c "The Early Years". Georgetown University Libraries. November 11, 2000. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Barringer, George M. (November 11, 2000). "The French Sulpicians". Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2007. Georgetown Universities Libraries Special Collections

- ^ "History & Traditions". Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ McNeal, J. Preston W (1911). "Leonard Neale". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ O'Gorman 1895, p. 281

- ^ a b "The Federal Charter". Georgetown University. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 20

- ^ a b O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 28

- ^ Shaver, Katherine (November 15, 2015). "Georgetown University to rename two buildings that reflect school's ties to slavery". Washington Post. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ Murphy, SJ, Thomas (2001). Jesuit Slaveholding in Maryland, 1717–1838 (PDF). New York: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0815340522. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ Pope, Michael (November 17, 2015). "The Hidden History Of How Slavery Funded Georgetown University". WAMU. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ Swarns, Rachel (April 17, 2016). "272 Slaves Were Sold to Save Georgetown. What Does It Owe Their Descendants?". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ^ Kathryn Brand, "The Jesuits' Slaves", The Georgetown Voice, 8 February 2007, accessed 25 April 2016

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 35

- ^ "History" (PDF). Georgetown University School of Medicine. March 23, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- ^ "The Academy becomes a College". November 11, 2000. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2007. Georgetown Universities Libraries Special Collections

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 25

- ^ "Georgetown Special Collections: University Archive". October 6, 2004. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2007. Georgetown Universities Libraries Special Collections

- ^ a b "Battalion History". The HOYA Battalion. August 4, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Brown, Erin (Spring 2004). "Mask & Bauble Dramatic Society". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2004-06-06. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 24

- ^ Shea 1891, p. 190

- ^ a b Goundrey, Mary (January 23, 2004). "Georgetown: Fighting for Survival". The Hoya. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ^ Devitt, E.I. (1909). "Georgetown University". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 36

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 37

- ^ Curran 1993, pp. 246–248

- ^ "Georgetown Traditions: The Blue & Gray". HoyaSaxa.com. August 17, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ DeGioia, John J. (May 17, 2008). "Georgetown College Commencement 2008". Georgetown University Office of the President. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ Carter & Wilder 2009, p. 229

- ^ "A Little History". Georgetown University Law Center. October 11, 2007. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Mlyniec, Wally (June 17, 2003). "The Law Center's Third and Fourth Home". Georgetown University Law Center. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ "Third Grammar Class, Second Section, on the steps of Healy Hall at Georgetown University". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2007. Loyola Notre Dame Library

- ^ Vincent, Gérard; Dethomas, Anne-Marie (1987). Sciences po: Histoire d'une réussite [Sciences Po: Story of Success] (in French). p. 200. ISBN 978-2-259-26077-0. Retrieved June 21, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Leon Dostert, Director of Georgetown University's Institute of Languages and Linguistics". repository.library.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-22.

- ^ "Dental History Page 2". Georgetown University Alumni Association. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ^ Amendolia, Marissa (February 19, 2009). "In an Age of Protest, A Changing Georgetown Found Its Niche". The Hoya. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, pp. 91

- ^ "History". Georgetown University. 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "Georgetown University history: Co-Ed". Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2007. About Georgetown Archived 2008-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Timiraos, Nick (April 1, 2003). "Areen Outlines Women's Role". The Hoya. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ Garbitelli, Elizabeth (March 16, 2012). "First Black Undergraduate Dies". The Hoya. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, pp. 109

- ^ "3 Named to Board of Georgetown U." The Washington Post. July 25, 1970. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, pp. 101, 104

- ^ Palko, Ian A. (January 21, 2000). "Today's Georgetown Takes Shape". The Hoya. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, pp. 122

- ^ Sullivan, Tim (February 16, 2001). "DeGioia Named Next GU President". The Hoya. Retrieved July 17, 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Timiraos, Nick (January 16, 2004). "Georgetown Finishes $1 Billion Campaign". The Hoya. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 81

- ^ "Dental History Page 4". Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2007. Georgetown University Alumni Association

- ^ Lyons, Emily (October 9, 1998). "GSB Takes New Name". The Hoya. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Spindle, Lindsey (July 30, 2003). "Georgetown University School of Nursing and Health Studies Appoints New Director of Development". Georgetown University. Archived from the original on March 21, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2007. Office of Communications

- ^ "Biography". Georgetown University. February 2005. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009. Office of the President

- ^ Parham, Connie; Myers, Yoshi (January 18, 2008). "Georgetown Opens Liaison Office at Fudan University". The Hoya. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Georgetown Advancing Interreligious Understanding". Georgetown University. April 2, 2007. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Tillman 1994, pp. 61–62

- ^ Rafferty, Steve (2006-01-13). "Saudi Prince Gives GU $20M". The Hoya. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ "Georgetown University marks inauguration of Qatar campus". The Peninsula. April 13, 2006. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 119

- ^ McCarthy, Ellen (January 25, 2008). "Exorcist steps". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Hartigan, Erin (2009). "The Tombs". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ "MAC to Millennium". University of Maryland Archives. November 24, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Chen, Vivian (March 13, 2008). "That's so not Georgetown: College Road Trip". The Georgetown Voice. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Matthews, J. Scott (February 7, 2002). "Memento writer visits campus". The Georgetown Voice. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ Bacic, Ryan (December 3, 2017). "Meet the tough professor who inspired Jonathan Nolan and John Mulaney". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burns, James Aloysius (1908). The Catholic School System in the United States. New York: Benziger Brothers.

- Carter, Cynthia Jacobs; Wilder, L. Douglas (2009). Freedom in My Heart. National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0127-1.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (1993). The Bicentennial History of Georgetown University. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-485-6.

- Easby-Smith, James Stanislaus (1907). Georgetown University in the District of Columbia, 1789-1907, Its Founders, Benefactors, Officers, Instructors and Alumni. New York: Lewis Publishing Company. ISBN 1-150-14481-5.

- Nevils, William Coleman (1934). Miniatures of Georgetown: Tercentennial Causeries. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. OCLC 8224468.

- O'Gorman, Thomas (1895). A History of the Roman Catholic Church in the United States. New York: Christian Literature Co. ISBN 1-150-14481-5.

- O'Neill, Paul R.; Williams, Paul K. (2003). Georgetown University. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-1509-4.

- Shea, John Gilmary (1891). Memorial of the First Century of Georgetown College, D. C.: Comprising a History of Georgetown University. Vol. 3. New York: P. F. Collier. pp. 178–196, 214–234. OCLC 612832863. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Tillman, Seth P. (1994). Georgetown's School of Foreign Service: The First 75 Years. Washington, D.C.: Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. OCLC 32749296.

- Warner, William W. (1994). At peace with all their neighbors: Catholics and Catholicism in the national capital, 1787-1860. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-557-7.

External links

[edit]- Georgetown University homepage

- Georgetown University Libraries Special Collection on Georgetown History Archived 2010-06-14 at the Wayback Machine