Forward contract

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

In finance, a forward contract, or simply a forward, is a non-standardized contract between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a specified future time at a price agreed on in the contract, making it a type of derivative instrument.[1][2] The party agreeing to buy the underlying asset in the future assumes a long position, and the party agreeing to sell the asset in the future assumes a short position. The price agreed upon is called the delivery price, which is equal to the forward price at the time the contract is entered into.

The price of the underlying instrument, in whatever form, is paid before control of the instrument changes. This is one of the many forms of buy/sell orders where the time and date of trade is not the same as the value date where the securities themselves are exchanged. Forwards, like other derivative securities, can be used to hedge risk (typically currency or exchange rate risk), as a means of speculation, or to allow a party to take advantage of a quality of the underlying instrument which is time-sensitive.

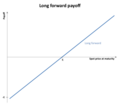

Payoffs

[edit]The value of a forward position at maturity depends on the relationship between the delivery price () and the underlying price () at that time.

- For a long position this payoff is:

- For a short position, it is:

Since the final value (at maturity) of a forward position depends on the spot price which will then be prevailing, this contract can be viewed, from a purely financial point of view, as "a bet on the future spot price"[3]

How a forward contract works

[edit]Suppose that Bob wants to buy a house a year from now. At the same time, suppose that Alice currently owns a $100,000 house that she wishes to sell a year from now. Both parties could enter into a forward contract with each other. Suppose that they both agree on the sale price in one year's time of $104,000 (more below on why the sale price should be this amount). Alice and Bob have entered into a forward contract. Bob, because he is buying the underlying, is said to have entered a long forward contract. Conversely, Alice will have the short forward contract.

At the end of one year, suppose that the current market valuation of Alice's house is $110,000. Then, because Alice is obliged to sell to Bob for only $104,000, Bob will make a profit of $6,000. To see why this is so, one needs only to recognize that Bob can buy from Alice for $104,000 and immediately sell to the market for $110,000. Bob has made the difference in profit. In contrast, Alice has made a potential loss of $6,000, and an actual profit of $4,000.

The similar situation works among currency forwards, in which one party opens a forward contract to buy or sell a currency (e.g. a contract to buy Canadian dollars) to expire/settle at a future date, as they do not wish to be exposed to exchange rate/currency risk over a period of time. As the exchange rate between U.S. dollars and Canadian dollars fluctuates between the trade date and the earlier of the date at which the contract is closed or the expiration date, one party gains and the counterparty loses as one currency strengthens against the other. Sometimes, the buy forward is opened because the investor will actually need Canadian dollars at a future date such as to pay a debt owed that is denominated in Canadian dollars. Other times, the party opening a forward does so, not because they need Canadian dollars nor because they are hedging currency risk, but because they are speculating on the currency, expecting the exchange rate to move favorably to generate a gain on closing the contract.

In a currency forward, the notional amounts of currencies are specified (ex: a contract to buy $100 million Canadian dollars equivalent to, say US$75.2 million at the current rate—these two amounts are called the notional amount(s)). While the notional amount or reference amount may be a large number, the cost or margin requirement to command or open such a contract is considerably less than that amount, which refers to the leverage created, which is typical in derivative contracts.

Example of how forward prices should be agreed upon

[edit]Continuing on the example above, suppose now that the initial price of Alice's house is $100,000 and that Bob enters into a forward contract to buy the house one year from today. But since Alice knows that she can immediately sell for $100,000 and place the proceeds in the bank, she wants to be compensated for the delayed sale. Suppose that the risk free rate of return R (the bank rate) for one year is 4%. Then the money in the bank would grow to $104,000, risk free. So Alice would want at least $104,000 one year from now for the contract to be worthwhile for her – the opportunity cost will be covered.

Spot–forward parity

[edit]For liquid assets ("tradeables"), spot–forward parity provides the link between the spot market and the forward market. It describes the relationship between the spot and forward price of the underlying asset in a forward contract. While the overall effect can be described as the cost of carry, this effect can be broken down into different components, specifically whether the asset:

- pays income, and if so whether this is on a discrete or continuous basis

- incurs storage costs

- is regarded as

- an investment asset, i.e. an asset held primarily for investment purposes (e.g. gold, financial securities);

- or a consumption asset, i.e. an asset held primarily for consumption (e.g. oil, iron ore etc.)

Investment assets

[edit]For an asset that provides no income, the relationship between the current forward () and spot () prices is

where is the continuously compounded risk free rate of return, and T is the time to maturity. The intuition behind this result is that given you want to own the asset at time T, there should be no difference in a perfect capital market between buying the asset today and holding it and buying the forward contract and taking delivery. Thus, both approaches must cost the same in present value terms. For an arbitrage proof of why this is the case, see Rational pricing below.

For an asset that pays known income, the relationship becomes:

- Discrete:

- Continuous:

where the present value of the discrete income at time , and is the continuously compounded dividend yield over the life of the contract. The intuition is that when an asset pays income, there is a benefit to holding the asset rather than the forward because you get to receive this income. Hence the income ( or ) must be subtracted to reflect this benefit. An example of an asset which pays discrete income might be a stock, and an example of an asset which pays a continuous yield might be a foreign currency or a stock index.

For investment assets which are commodities, such as gold and silver, storage costs must also be considered. Storage costs can be treated as 'negative income', and like income can be discrete or continuous. Hence with storage costs, the relationship becomes:

- Discrete:

- Continuous:

where the present value of the discrete storage cost at time , and is the continuously compounded storage cost where it is proportional to the price of the commodity, and is hence a 'negative yield'. The intuition here is that because storage costs make the final price higher, we have to add them to the spot price.

Consumption assets

[edit]Consumption assets are typically raw material commodities which are used as a source of energy or in a production process, for example crude oil or iron ore. Users of these consumption commodities may feel that there is a benefit from physically holding the asset in inventory as opposed to holding a forward on the asset. These benefits include the ability to "profit from" (hedge against) temporary shortages and the ability to keep a production process running,[1] and are referred to as the convenience yield. Thus, for consumption assets, the spot-forward relationship is:

- Discrete storage costs:

- Continuous storage costs:

where is the convenience yield over the life of the contract. Since the convenience yield provides a benefit to the holder of the asset but not the holder of the forward, it can be modelled as a type of 'dividend yield'. However, it is important to note that the convenience yield is a non cash item, but rather reflects the market's expectations concerning future availability of the commodity. If users have low inventories of the commodity, this implies a greater chance of shortage, which means a higher convenience yield. The opposite is true when high inventories exist.[1]

Cost of carry

[edit]The relationship between the spot and forward price of an asset reflects the net cost of holding (or carrying) that asset relative to holding the forward. Thus, all of the costs and benefits above can be summarised as the cost of carry, . Hence,

- Discrete:

- Continuous:

Relationship between the forward price and the expected future spot price

[edit]

The market's opinion about what the spot price of an asset will be in the future is the expected future spot price.[1] Hence, a key question is whether or not the current forward price actually predicts the respective spot price in the future. There are a number of different hypotheses which try to explain the relationship between the current forward price, and the expected future spot price, .

The economists John Maynard Keynes and John Hicks argued that in general, the natural hedgers of a commodity are those who wish to sell the commodity at a future point in time.[4][5] Thus, hedgers will collectively hold a net short position in the forward market. The other side of these contracts are held by speculators, who must therefore hold a net long position. Hedgers are interested in reducing risk, and thus will accept losing money on their forward contracts. Speculators on the other hand, are interested in making a profit, and will hence only enter the contracts if they expect to make money. Thus, if speculators are holding a net long position, it must be the case that the expected future spot price is greater than the forward price.

In other words, the expected payoff to the speculator at maturity is:

- , where is the delivery price at maturity

Thus, if the speculators expect to profit,

- , as when they enter the contract

This market situation, where , is referred to as normal backwardation. Forward/futures prices converge with the spot price at maturity, as can be seen from the previous relationships by letting T go to 0 (see also basis); then normal backwardation implies that futures prices for a certain maturity are increasing over time. The opposite situation, where , is referred to as contango. Likewise, contango implies that futures prices for a certain maturity are falling over time.[6]

Futures versus Forwards

[edit]Forward contracts are very similar to futures contracts, except they are not exchange-traded, or defined on standardized assets.[7] Forwards also typically have no interim partial settlements or "true-ups" in margin requirements like futures, that is the parties do not exchange additional property securing the party at gain and the entire unrealized gain or loss builds up while the contract is open. Therefore, forward contracts have a significant counterparty risk which is also the reason why they are not readily available to retail investors.[8] However, being traded over the counter (OTC), forward contracts specification can be customized and may include mark-to-market and daily margin calls.

Having no upfront cashflows is one of the advantages of a forward contract compared to its futures counterpart. Especially when the forward contract is denominated in a foreign currency, not having to post (or receive) daily settlements simplifies cashflow management.[9]

Compared to the futures markets it is very difficult to close out one's position, that is to rescind the forward contract. For instance while being long in a forward contract, entering short into another forward contract might cancel out delivery obligations but adds to credit risk exposure as there are now three parties involved. Closing out a contract almost always involves reaching out to the counterparty.[10]

Compared to their futures counterparts, forwards (especially Forward Rate Agreements) need convexity adjustments, that is a drift term that accounts for future rate changes. In futures contracts, this risk remains constant whereas a forward contract's risk changes when rates change.[11]

Outright versus Premium

[edit]Outright prices, as opposed to premium points or forward points, are quoted in absolute price units. Outrights are used in markets where there is no (unitary) spot price or rate for reference, or where the spot price (rate) is not easily accessible.[12]

Conversely, in markets with easily accessible spot prices or basis rates, in particular the Foreign exchange market and OIS market, forwards are usually quoted using premium points or forward points. That is using the spot price or basis rate as reference forwards are quoted as the difference in pips between the outright price and the spot price for FX, or the difference in basis points between the forward rate and the basis rate for interest rate swaps and forward rate agreements.[13]

Note: The term outright is used in the futures markets in a similar way but is contrasted with futures spreads instead of premium points, which is more than just a quoting convention, and in particular involves the simultaneous transaction in two outright futures.[14]

Rational pricing

[edit]If is the spot price of an asset at time , and is the continuously compounded rate, then the forward price at a future time must satisfy .

To prove this, suppose not. Then we have two possible cases.

Case 1: Suppose that . Then an investor can execute the following trades at time :

- go to the bank and get a loan with amount at the continuously compounded rate r;

- with this money from the bank, buy one unit of asset for ;

- enter into one short forward contract costing 0. A short forward contract means that the investor owes the counterparty the asset at time .

The initial cost of the trades at the initial time sum to zero.

At time the investor can reverse the trades that were executed at time . Specifically, and mirroring the trades 1., 2. and 3. the investor

- ' repays the loan to the bank. The inflow to the investor is ;

- ' settles the short forward contract by selling the asset for . The cash inflow to the investor is now because the buyer receives from the investor.

The sum of the inflows in 1.' and 2.' equals , which by hypothesis, is positive. This is an arbitrage profit. Consequently, and assuming that the non-arbitrage condition holds, we have a contradiction. This is called a cash and carry arbitrage because you "carry" the asset until maturity.

Case 2: Suppose that . Then an investor can do the reverse of what he has done above in case 1. This means selling one unit of the asset, investing this money into a bank account and entering a long forward contract costing 0.

Note: if you look at the convenience yield page, you will see that if there are finite assets/inventory, the reverse cash and carry arbitrage is not always possible. It would depend on the elasticity of demand for forward contracts and such like.

Extensions to the forward pricing formula

[edit]Suppose that is the time value of cash flows X at the contract expiration time . The forward price is then given by the formula:

The cash flows can be in the form of dividends from the asset, or costs of maintaining the asset.

If these price relationships do not hold, there is an arbitrage opportunity for a riskless profit similar to that discussed above. One implication of this is that the presence of a forward market will force spot prices to reflect current expectations of future prices. As a result, the forward price for nonperishable commodities, securities or currency is no more a predictor of future price than the spot price is - the relationship between forward and spot prices is driven by interest rates. For perishable commodities, arbitrage does not have this

The above forward pricing formula can also be written as:

Where is the time t value of all cash flows over the life of the contract.

For more details about pricing, see forward price.

Theories of why a forward contract exists

[edit]Allaz and Vila (1993) suggest that there is also a strategic reason (in an imperfect competitive environment) for the existence of forward trading, that is, forward trading can be used even in a world without uncertainty. This is due to firms having Stackelberg incentives to anticipate their production through forward contracts.[15]

See also

[edit]- 988 transaction

- Derivative (finance)

- Forward exchange market

- Forward market

- Forward price

- Futures contract

- Hedging

- Non-deliverable forward

- Option

- Swap (finance)

Other types of trade contracts:

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d John C Hull, Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (6th edition), Prentice Hall: New Jersey, USA, 2006, 3

- ^ Understanding Derivatives: Markets and Infrastructure, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

- ^ Gorton, Gary; Rouwenhorst, K. Geert (2006). "Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures" (PDF). Financial Analysts Journal. 62 (2): 47–68. doi:10.2469/faj.v62.n2.4083.

- ^ J.M. Keynes, A Treatise on Money, London: Macmillan, 1930

- ^ J.R. Hicks, Value and Capital, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939

- ^ Contango Vs. Normal Backwardation Archived 2014-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, Investopedia

- ^ Forward Contract on Wikinvest

- ^ "Understanding Forward Contracts vs. Futures Contracts". Investopedia. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Understanding FX Forwards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Forward Contract vs Futures Contract". Diffen. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Convexity Adjustment Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Steiner, Bob (September 2012). Key Financial Market Concepts (2nd ed.). Financial Times/Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780273750284.

- ^ "Forward Points". Investopedia. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Instrument Types Available on CME Globex". CME Globex. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Allaz, Blaise; Vila, Jean-Luc (1993). "Cournot Competition, Forward Markets and Efficiency". Journal of Economic Theory. 59 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1006/jeth.1993.1001.

General and cited references

[edit]- John C. Hull (2000), Options, Futures and Other Derivatives, Prentice-Hall.

- Abraham Lioui & Patrice Poncet (March 30, 2005), Dynamic Asset Allocation with Forwards and Futures, Springer

- Keith Redhead (31 October 1996), Financial Derivatives: An Introduction to Futures, Forwards, Options and Swaps, Prentice-Hall

- Forward Contract on Wikinvest

Further reading

[edit]- Allaz, B. and Vila, J.-L., Cournot competition, futures markets and efficiency, Journal of Economic Theory 59,297-308.

- Understanding Derivatives: Markets and Infrastructure Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Financial Markets Group

- Forward Contract Definition - Investopedia