Prospect Bluff Historic Sites

British Fort | |

| |

| Location | Franklin County, Florida |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Sumatra |

| Coordinates | 29°56′N 85°1′W / 29.933°N 85.017°W |

| Area | 7 acres (2.8 ha) |

| Built | 1814 |

| NRHP reference No. | 72000318[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 23, 1972 |

| Designated NHL | February 23, 1972[2] |

Prospect Bluff Historic Sites (until 2016 known as Fort Gadsden Historic Site, and sometimes written as Fort Gadsden Historic Memorial)[4] is located in Franklin County, Florida, on the Apalachicola River, 6 miles (9.7 km) SW of Sumatra, Florida. The site contains the ruins of two forts.

The earlier and larger one was built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812. They allowed the members of the disbanded Corps of Colonial Marines, made up largely of fugitive slaves, and Creek tribesmen to occupy it after the British evacuated Florida in 1815, deliberately leaving their munitions behind. At that point, since the British had not named it, Americans started referring to it as Negro Fort. It was destroyed in a river attack from U.S. forces in 1816.

Fort Gadsden was built in 1818 within the former walls of the former Negro Fort.

The site has been known by several other names at various times, including Prospect Bluff,[5]: 48 British post,[5]: 48 [6] Nicholls' Fort, Blount's Fort,[7][8] Fort Blount,[9] African Fort, and Fort Apalachicola.[10]: 60 The local natives called the land Achackwheithle.[11]

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places and named a National Historic Landmark in 1972, the Prospect Bluff Historic Sites was acquired by the Apalachicola National Forest in 1940 and is managed by the U.S. Forest Service.[2] The process of memorializing the site began in 1961, when the Apalachicola National Forest issued the State of Florida a term special use permit for an area of approximately 78 acres (32 ha) including the site to be run as a state park. Administration of the site reverted to the federal government[4] in the 1990s. The site contains interpretive signage, picnic area with pavilion, and rest rooms.[4]

Prospect Bluff

[edit]The site of both Negro Fort and the later Fort Gadsden was Prospect Bluff, "a fine bluff overlooking the Apalachicola River,"[12]: 18 whose modest elevation of 12 feet (3.7 m) and the swamp that almost surrounded it (description below) gave it a natural military strength. The name parallels the Spanish one, Loma de Buena Vista,[13][14]: 8 literally "hill with a good view".[15]

Accessible only by river then, the site was and is still remote. The river was the boundary between East Florida and West Florida during the British Florida period (1763–1783) and the second Spanish Florida period (1783–1821). By modern land route it is 198 miles (319 km) from Pensacola and 271 miles (436 km) from St. Augustine. The area was sparsely populated, and in the twentieth century a large portion became the Apalachicola National Forest. The river was of intense interest to the British, who saw it as an undefended entry into the United States through Georgia. It was of no interest to the Spaniards; it led nowhere they cared about. Spanish forces in Florida were limited and Spain was far less committed to Florida than it was to its other colonies, most of them much more productive. Spain's inability to police its borders or return fugitive slaves was central to Florida's transfer to the United States in 1821.

Control of Prospect Bluff meant control of the river, which had served as a transportation artery for centuries. More recently, it had enabled raiding parties to go upriver into Georgia and the Mississippi Territory via the Chattahoochee and especially the Flint River. The attacks were made on plantations, which had few if any defenses. These parties, besides coming back with material goods, saw to it that the slaves of the raided plantations could get free. This was a great economic blow to the slave owners (slaves were expensive), and an ideological affront as well,[12]: 12–13 leaving them insecure and angry.

Prospect Bluff was valuable militarily not only because of the elevation its name suggests, but because it was at a "strategic location",[13] a bend in the river, giving an important sight advantage over any boat.

Before 1814

[edit]The Florida panhandle was mostly wilderness before 1814. Its population at the time is unknown, except for isolated reports. As in the rest of Florida, there were many Native American refugees from the United States, who merged into a new ethnicity, Seminoles. It provided excellent cover for escaped slaves, who, since they shared a common enemy, got along with the Seminoles fairly well; "over time, a bond developed between escaped Africans and the Seminoles that only increased with time and white pressure for their return".[12]: 12–13 Some became black Seminoles. There was "reciprocal respect and affection"; the former slaves, who knew English, served as interpreters.[16]: 6 This predecessor of the Underground Railroad ran south.[17][18][19] The biggest issue about the area discussed by whites was how to get escaped slaves back, or get compensation for them, and prevent or reduce future escapes. The return of Native Americans was unwanted,[20]: 243 and they were soon forcibly removed from Florida as well.

As was customary in pre-railroad times, settlement took place first along rivers. The name Apalachicola River derives its name from Apalachicola Province on what is now the Chattahoochee River (the Spanish regarded what is now the Chattahoochee as part of the Apalachicola River). Settlement at Prospect Bluff by maroons (escaped slaves and their descendants), Seminoles, and a few Europeans is documented at the end of the eighteenth century.

In January 1783 a conference was held in St. Augustine between the representatives of the British Crown—Governor Patrick Tonyn, Brigadier General Archibald McArthur, and Thomas Brown, the superintendent of Indian affairs—and the head men and principal warriors of the towns of the Upper and the Lower Creeks, who complained of the long distance they must travel to the stores from which they obtained their supplies. The Indians offered protection to merchants who would move their stores to locations closer to their territory, and pointed out the Apalachicola River as a suitable place for a trading house. The Creeks said it was not only more convenient for themselves, but also much nearer to the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee Indians, and requested that the house of Panton, Leslie & Company, who had been supplying them with goods, should be solicited to settle there for that purpose.

William Panton was present at the conference, and agreed with the Indians to establish a store at such a place as he or his co-partners might find suitable between the forks of Flint river and the mouth of the Apalachicola River, provided that letters of license were issued to him and his partners. The agreement was confirmed by the Crown, and the traders were granted the necessary license.[21] Their store opened in 1784, by which time Spain had regained possession of Florida, at Fort San Marcos de Apalache (modern St. Marks, Florida). This store was attacked and looted by the adventurer William Augustus Bowles in 1792 and again in 1800, at which point it ceased operations.[22]: 60

A trading post run by John Forbes and Company, successors to Panton, Leslie & Company, was set up in 1804 at the more defensible Prospect Bluff at the request of "Indians" ("Mickosuckees" is the only ethnicity mentioned). It was "manned by Edmund Doyle with some assistance from William Hambly, an Indian trader with years of experience in the area."[12]: 18 [22]: 63 Doyle and Hambly "each owned plantations higher up the river, at Spanish Bluff on the west bank and near present-day Bristol on the east bank."[14]: 7

The site of the trading post was inside the walls of the Fort, built around it; this explains why the precise site has never been identified. It included a building for storing hides (what the Native Americans had to trade), quarters for negro slaves, and a cow pen for several hundred cattle that were raised nearby. During the War of 1812, British troops ransacked the store and freed the slaves.

Figures on the number of maroons who settled in the surrounding area range from 300 to 1,000.[23] The blacks developed plantations extending up to 50 miles along the river.[9][22]: 81 A report from 1812 mentions over 36 cleared acres and 1,200 cattle,[22]: 63 and they lived in "large and well-built cabins".[20]: 233 Their crops were peas, beans, corn, and rice.[20]: 233

British Post (1814–15)

[edit]Construction of the fort began in May 1814, when the British seized the trading post of John Forbes and Company.[24]

The British launched an invasion of Pensacola during the War of 1812 and occupied it[25] until General Andrew Jackson took the town on November 7, 1814.[26][27] The British forces, over 100 officers and men led by a Brevet Captain of the Royal Marines, George Woodbine,[20]: 42 made camp at the only community between Pensacola and St. Marks: the trading post of John Forbes and Company, surrounded by negro plantations.

It was located at Prospect Bluff. Woodbine began to train local Native Americans as well as escaped slaves.[16]: 15 [28][29] Nicolls recruited the ex-slaves into the new (black) Corps of Colonial Marines. They were well-armed, well-equipped, and underwent drills; many had been in training for months.[30]: 69 He also assembled and trained more than five hundred Creek and Seminole Indians by February 1815, but they came from a different culture, did not like being trained,[20]: 63 and did not have the incentive of being protected from American re-enslavement. Nicolls found the ex-slaves superior as soldiers, reporting that his black recruits had enlisted "with the strictest good faith and conduct, so much so, that out of 1,500 of them I never had occasion to punish one of them". He added that in contrast with British soldiers, "they would not get drunk".[20]: 63

They were preparing to attack Georgia when news arrived of the end of the war.[31][32] The British paid off the Colonial Marines (at the same rate as the white Marines) and withdrew from Florida. On May 16, 1815, the British evacuated the last of the garrison there.

Blacks and Native Americans under Nicolls' direction built two forts on the Apalachicola River. The larger and more important one was to be on the border of Georgia, at the juncture of the Flint and the Chattahoochee Rivers, in modern Chattahoochee, Florida, and was to serve as the base for a U.S. invasion.[33]: 9 Time only permitted the construction of a small wooden structure, which Nicolls called Fort Apalachicola, but is today referred to as Nicolls' Outpost.[34]

The larger one, which actually was built and was intended to be a supply depot for Nicolls' Outpost,[33]: 21, 47 did not have a name; it was referred to simply as the British Post. It was 15 miles (24 km) above the river mouth and 60 miles (97 km) south of Nicolls' Outpost and the border of Georgia. The construction of the larger fort was described by Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines in a letter of May 14, 1816 to Andrew Jackson, who had charged him with destroying the Fort:

The ramparts and parapets built of hewn timber filled in with earth, mounting 9 to 12 pieces of Cannon, several of which are very large, with some mortars and Howitzers. It has a deep ditch intended to be filled with water, but was dry when seen by my informants, two or three months ago. The work is nearly square and extends over near two acres [0.81 ha] of ground, has Comfortable barracks, and large stone houses inside. It is rendered inaccessible by land, except a narrow pass up near the margin of the river, by reason of an impenetrable swamp in the rear and extending to the river above.[35]

The fort was very well provided with ordnance:

It included 4 twenty-four-pound cannons, 4 six-pound cannons, beside a field piece and a howitzer. In addition there were found 2,500 stands of muskets with accoutrements, 500 carbines and 500 swords ... 300 quarter-casks of rifle powder and 162 barrels of cannon powder, besides other stores and clothing.[22]: 80–81

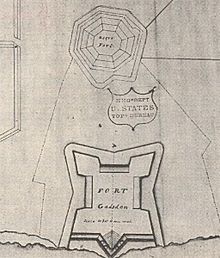

The area enclosed by the fort was 7 acres (34,000 sq yd; 2.8 ha); on the eastern corners (those most vulnerable to attack) were bastions with walls 15 feet (4.6 m) high and 18 feet (5.5 m) thick.[12]: 18 [36]

The magazine area of the fort was located about 500 feet from the river bank, and consisted of an octagonal blockhouse holding the principal magazine. This was surrounded by an extensive star-shaped enclosure covering about 16 acres with bastions on the eastern corners. The ravelin along the river with cannon was 15 feet high and 18 feet thick.[4]

Gaines estimated that 900 Native American warriors and 450 armed blacks inhabited the fort.[37][38]

A miniature replica of the later Fort Gadsden was constructed in the 1970s; a picture is in the State Archives of Florida.[39]

Negro Fort (1815–16)

[edit]When the British withdrew, they deliberately left all their weapons, hoping that the locals would use them to defend themselves from U.S. attempts to re-enslave them, just as African and Native Americans had assisted the British during the American War of Independence.[5]: 48–49 Most of the Native Americans (Seminoles and Red Stick Creeks) warriors who remained behind abandoned the fort soon afterwards.[40]

Some[who?] remained, along with many of the trained soldiers of the disbanded Corps of Colonial Marines, which was a British Army regiment consisting of freed slaves. [citation needed]

Over the next year the fort became a growing colony of escaped slaves from Georgia and the Mississippi Territory, and became known as the Negro Fort.[41][42][43] It was the center of the largest community of free negroes in North America before the U.S. Civil War.

The fort, located as it was near the border, was seen by the U.S. as "a beacon of light to restless and rebellious slaves,"[18] "a center of hostility and above all a threat to the security of their slaves,"[44] "a direct threat to the slave-holding interests rapidly flocking to the newly opened lands in what is today Mississippi and Alabama."[12]: 20 On April 8, 1816, General Jackson ordered General Gaines to "take care of the situation", because the Fort "ought to be blown up"; it was only fomenting "rapine and plunder", and he should "return the stolen Negros and plunder to their rightful owners".[12]

Having done so, on April 23 he then complained to the West Florida military governor Mauricio de Zúñiga, asking

whether that fort has been built by the government of Spain — and whether the negroes, who garrison it, are considered subjects of his Catholic Majesty — and if not by the authority of Spain — by whom, under whose orders, has it been established[?]

He informed Zúñiga that:

Secret practices to inveigle Negroes from the frontier citizens of Georgia as well as from the Cherokee and Creek nations of Indians are still continued by this Banditti [sic; he means the garrison] and the Hostile Creeks. This is a state of things which cannot fail to produce much injury to the neighboring settlements and incite Irritations which may ultimately endanger the peace of the nation and interrupt that good understanding that so happily exists between our governments.

He insisted on the "return to our citizens and the friendly Indians inhabiting our Territory those Negroes now in the said fort and which have been stolen and enticed from them." This conduct "will not be tolerated by our government and if not put down by the Spanish Authority will compel us in self Defence to destroy them."[45]: 22–23

After Zúñiga's reply of May 26, 1816, informing Jackson that he could not act "unless I receive the Orders of my Captain General [in Cuba[46]: 25 ] and the necessary Supplies",[45]: 41–43 Jackson proceeded with his plans to destroy the Fort.

The first step was the construction of Fort Scott, located at a key military point upriver, the west bank of the Flint River where it empties into the Apalachicola, in the southwestern corner of Georgia. Boats supplying Fort Scott had to go up the Apalachicola River and past the Negro Fort. The supply boats were escorted by two gunboats. "Gaines obviously wanted to provoke an attack to justify the stronghold's destruction."[16]: 17 When shots were fired from the Fort at passing boats, this was all the excuse for action Gaines needed. On July 27, 1816, a "hot shot" (a cannonball heated to a red glow in the gunboat's galley) from the American forces entered the opening to the fort's powder magazine, igniting an explosion that was heard more than 100 miles (160 km) away in Pensacola, and destroyed the fort, killing all but 30 of 300 occupants.[47] It has been called "the single deadliest cannon shot in American history."[48] It was also "the largest battle in history between fugitive slaves and U.S. forces seeking to reenslave them."[5]: 46

Spain protested the violation of its soil, but according to historian John K. Mahon, it "lacked the power to do more."[49]

A former commemorative plaque at the scene reads as follows:

BRITISH FORT MAGAZINEIt is hard to imagine the horrible scene that greeted the first Americans to stand here on the morning of July 27, 1816. The remains of 230 persons killed in the magazine explosion lay scattered about. They also found an arsenal of ten cannons, 2,500 muskets and over 150 barrels of black powder. Some original timbers from the octagonal magazine were uncovered here by excavations.

The trading post of John Forbes and Company, storekeeper Edward Doyle, was reestablished following the destruction of the fort.[50]: 109

Fort Gadsden (1818–21)

[edit]To secure the militarily significant Prospect Bluff, protect commerce on the river, prevent the recreation of a fugitive slave community—new fugitives were arriving—, and as a base for his further invasion of Florida, in 1818 General Jackson directed Lieutenant James Gadsden, of the Army Corps of Engineers, to rebuild the fort, which he did within the earthworks that had protected Negro Fort, as it was much smaller.[51][52]: 80 The fort needed a new name; Jackson named it Fort Gadsden.[53] However, an aide to General Andrew Jackson reported to his superior in August 1818 that Fort Gadsden was "a temporary work, hastily erected, and of perishable materials, without constant repair, it could not last more than four or five years."[54] It was abandoned in 1821, the year Florida became a U.S. territory and there was no longer a national border to defend.

Fort Gadsden had no direct involvement in any military endeavor, either in 1818–1821 or during the Civil War.

Colinton

[edit]In 1820, Colin Mitchell would purchase the Forbes Lands, including Fort Gadsden. The following year he made plans to construct a city at the site, Colinton. The planned city would have had 4 squares and wharves for incoming steamboats. However, Mitchell's claim to the land would be found invalid, and Colinton was never built.[55]

"Milly Francis"

[edit]A marker at the site recalls the case of Milly Francis, a Creek girl who persuaded her father, Hillis Hadjo (Francis the Prophet), not to execute an American soldier who had inadvertently come into their territory. Her father was captured and hung at Fort St. Marks in 1818. She witnessed his hanging.[56]

Irvington remains

[edit]A steamboat, the Irvington, burned and sank in 1838 four miles north of the Site. The rusting boilers and some of the works thought to be from this ship were dredged from the river (when the river was being dredged for navigation) and can be seen at the Site.[5]: 52

Civil War (1862–1863)

[edit]During the American Civil War, Confederate troops occupied the fort, using it to protect communications from plantations in Georgia, Florida, and Alabama with the port of Apalachicola.[57] In July 1863, an outbreak of malaria forced its abandonment.[58]

Fort Gadsden given disproportionate emphasis at historic site

[edit]"The settlement of former slaves has been marginalized in and has largely receded from both the scholarly and popular imagination for much of the last [20th] century."[20]: 1–2

The most important moment in Prospect Bluff's history is arguably the Negro Fort period (1815–1816) and this is the period of significance cited in the National Register Nomination. However, the site was initially named for Fort Gadsden, much less significant historically. The Fort Gadsden Historic Site was created in 1961,[4] when racial divisions may have led to downplaying the battle, although other causes such as population displacement may have contributed as well.

The 2016 renaming of the site as Prospect Bluff Historic Sites does acknowledge in the name that more than Fort Gadsden existed there and uses a name that the residents of that area in the 19th century would have known it as.[citation needed]

Bicentennial activities

[edit]- On May 16–20, 2016, the National Park Service held a workshop with 50 participants on using technological tools to non-destructively investigate below a site's surface.[59][60]

- On October 22, 2016, the United States Forest Service commemorated 200 years since the tragic events of July 1816. There was a Seminole Color Guard, "descendants of Prospect Bluff Maroon community", with keynote speaker Chairman James E. Billie of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.[61] A video of the ceremony is available.

- The Florida Humanities Council funded a program that created virtual landscapes for 1816 Prospect Bluff as well as the Maroon community of Angola on the Manatee River.[62]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Cox, Dale (2020). The Fort at Prospect Bluff, The British Post on the Apalachicola and the Battle of Negro Fort. Old Kitchen Media. ISBN 978-0578634623.

- Millett, Nathaniel (2015). Maroons of Prospect Bluff and Their Quest for Freedom in the Atlantic World. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813060866.

- Saunt, Claudio (1999). A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733-1816. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521660432.

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register of Historical Places - Florida (FL), Franklin County". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. September 22, 2007. Archived from the original on October 4, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ a b British Fort Archived May 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine at National Historic Landmarks Program Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cox, Dale (2016). "The Defenses of Prospect Bluff (July 14, 1816)". exploresouthernmedia.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e Williams, Robert (December 1974). "Fort Gadsden Historic Site. National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Carlisle, Rodney P.; Carlisle, Loretta (2012). Forts of Florida. A Guidebook. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813040127.

- ^ Life of Andrew Jackson. James Parton, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1880. p. 393. [1] Archived June 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Giddings, Joshua Reed (1964). The exiles of Florida, or, The crimes committed by our government against the maroons, who fled from South Carolina, and other slave states, seeking protection under Spanish laws (1858). University of Florida Press. p. 46.

- ^ Nell, William C. (1855). The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Boston: Robert F. Wallcut. pp. 256–263.

- ^ a b Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 489

- ^ Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. (2003). Old Hickory's War. Andrew Jackson and the Quest for Empire. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807128678.

- ^ Clavin, Matthew J. (2019). The Battle of Negro Fort : the rise and fall of a fugitive slave community. New York. p. 22. ISBN 9781479837335.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Knetsch, Joe (2003). Florida's Seminole Wars 1817–1858. Arcadia. ISBN 9780738524245.

- ^ a b Kimbrough, Rhonda (2016). "Florida's Fort Gadsden 200th Anniversary". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Cox, Dale (2012). Nicolls' Outpost. A War of 1812 Fort at Chattahoochee, Florida. Old Kitchen Books. ISBN 9780692379363.

- ^ Matthew J. Clavin (October 12, 2015). Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers. Harvard University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-674-08822-1. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c Kenneth W. Porter (1996). Amos, Alcione M.; Senter, Thomas P. (eds.). The Black Seminoles. History of a Freedom-Seeking People. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0813014514.

- ^ Smith, Bruce (March 18, 2012). "For a century, Underground Railroad ran south". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ a b National Park Service. "Aboard the Underground Railway. British Fort". Archived from the original on May 14, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ McIver, Stuart (February 14, 1993). "Fort Mose's Call To Freedom. Florida's Little-known Underground Railroad Was The Escape Route Taken By Slaves Who Fled To The State In The 1700s And Established America's First Black Town". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Millett, Nathaniel (2013). The Maroons of Prospect Bluff and Their Quest for Freedom in the Atlantic World. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813044545.

- ^ Colin Mitchell (1831). Record in the Case of Colin Mitchell and Others, Versus the United States: Supreme Court of the United States. January Term, 1831. D. Green. pp. 298–300. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Boyd, Mark F. (1937), "Events at Prospect Bluff on the Apalachicola River, 1808-1818", Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 55–96, archived from the original on November 17, 2020, retrieved December 21, 2017

- ^ Usherwood, Elizabeth Ann (May 2011). "A Reanalysis of the Negro Fort 1814-1816. A Beacon of Hope on the Florida Frontier". Florida Anthropological Society Annual Meeting. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ Hughes & Brodine 2023, p. 825-827.

- ^ Matthew J. Clavin (October 12, 2015). Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers. Harvard University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-674-08822-1. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ John Innerarity (January 1931). "Letters of John Innerarity: The Seizure of Pensacola by Andrew Jackson, November 7, 1814". The Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 9 (3). Florida Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Dale Manuel (2004). Pensacola Bay: A Military History. Arcadia Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7385-1603-5. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ United States. Congress (1834). American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States ... Gales and Seaton. p. 605. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

Whereas, I have thought fit to send a Detachment of the Royal Marine Corps to the Creek Nations, for the purpose of training to arms, such [Native Americans] and others as may be friendly to, and willing to fight under, the Standard of His Majesty: I ..appoint you as an Auxiliary Second Lieutenant, of such Corps of Colonial Marines ... Given under my hand and seal, at Bermuda, this 25th day of July 1814.

- ^ Nathaniel Millet (August 8, 2017). "The Radicalism of the First Seminole War". In Nicole Eustace, Fredrika J. Teute (ed.). Warring for America: Cultural Contests in the Era of 1812. Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4696-3176-9. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Cox, Dale; Conrad, Rachael (2017). Fowltown: Neamathla, Tutalosi Talofa & the First Battle of the Seminole Wars. Old Kitchen Books. ISBN 9780692977880. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Historical Marker Database. "Nicolls' Outpost". Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ "New Orleans Expedition [Concluded.]". The Royal Gazette, Bermuda. April 22, 1815. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

'It is stated, upon very high authority, that there are about 10,000 Creek Indians ready to join our cause.' Perhaps such exaggerated figures were used by Cochrane to justify more resources being deployed on the Gulf Coast.

- ^ a b Cox, Dale (2015). Nicolls' outpost : a War of 1812 fort at Chattahoochee, Florida. Old Kitchen Books. ISBN 9780692379363.

- ^ Cox, Dale (2014). "Nicolls' Outpost - Chattahoochee, Florida. A Fort of the War of 1812". southernhistory.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Moser, Harold D.; Hoth, David R.; Hoemann, George H. (1994). The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Vol. IV: 1816-1820. University of Tennessee Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0870497782.

- ^ National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, British Fort, Aboard the Underground Railroad, archived from the original on May 14, 2017, retrieved December 22, 2017

- ^ American State Papers: Foreign Relations: Volume 4, pg 552 Letter from General Gaines dated May 22, 1815 'P.S. I learn that Nicholls [sic] ..is still at Appalachicola [sic], and that he has 900 Indians and 450 negroes under arms'

- ^ ADM 1/508 Letter from Admiral Cochrane to General Lambert dated February 3, 1815 'a coloured corps has been organised of from 300-400 men ... number of indians amounts to nearly 3000 men'.

- ^ "Miniature replica of Fort Gadsden for museum exhibit at park - Sumatra, Florida". State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. 1972. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Wasserman, Adam (2010). A People's History of Florida 1513–1876 (Revised ed.). Adam Wasserman. p. 167. ISBN 9781442167094.

- ^ Cox, Dale (2014). "Attack on the Fort at Prospect Bluff". exp loresouthernhistory.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ American State Papers: Foreign Relations: Volume 4, pg 551 has the testimony of a Royal Marine deserter from the Fort, sworn at Mobile on May 9, 1815, advising: 'the British left, with the Indians, between them three and four hundred negroes, taken from the United States, principally Louisiana'

- ^ Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War, pg. 23.

- ^ a b Jackson, Andrew (1994). "Letter to Mauricio de Zúñiga, April 23, 1816". The Papers of Andrew Jackson Vol. 4: 1816-1820. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0870497782. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Cox, Dale (2016). Fort Scott, Fort Hughes & Camp Recovery. Old Kitchen Books. ISBN 9780692704011.

- ^ Aptheker, 259.

- ^ Cox, Dale (2017). "Prospect Bluff Historic Sites". exploresouthernhistory.com. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ Mahon, 23-24.

- ^ Cox, Dale; Conrad, Rachael (2017). Fowltown: Neamathla, Tutalosi Talofa and the first battle of the Seminole Wars. Old Kitchen Books. ISBN 978-0692977880.

- ^ Cox, Dale (2008). "Fort Gadsden and the "Negro Fort" on the Apalachicola". ExploreSouthernHistory.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ Cox, Dale (2016). Fort Scott, Fort Hughes & Camp Recovery : three 19th century military sites in Southwest Georgia. Old Kitchen Books.

- ^ Mohlenbrock, Robert. This Land: A Guide to Eastern National Forests. University of California Press, 2006.

- ^ Greenlee, Marsha M. (December 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ "ARROW History Regional Timeline". Florida Natural Areas Inventory. 2005. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Florida Department of National Resources in cooperation with Florida Department of State. ""Millie Francis" (historical marker)". Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ USDA Forest Service (2011). Historic Fort Gadsden. The Archeology Channel. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Kramer, Joyce. River Rover Chronicles 2. Balboa Press, 2015

- ^ National Park Service, Midwest Archaeological Center (2016). "Current Archeological Prospection Advances for Non-destructive Investigations of Fort Gadsden, a War of 1812 Fort and Fight" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, National Park Service, Department of the Interior (2016). "Advances in Archeological Prospection. Fort Gadsen [sic]". Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture (2016). "You're invited to the 200th anniversary celebration of the Fort at Prospect Bluff in the Apalachicola National Forest" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Tragedy and Survival: Virtual Landscapes of 19th Century Florida Gulf Coast Maroons

References

[edit]- William Cooper Nell, "The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution: With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons". (1855).

- Herbert Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts. 5th edition. New York, NY: International Publishers, 1983 (1943).

- Boyd, Mark F. (1937), "Events at Prospect Bluff on the Apalachicola River, 1808-1818", Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, Florida Historical Society, pp. 55–96, JSTOR 30138273

- Foreign Office. British and foreign state papers Volume 6, 1818-1819. Piccadilly, London: James Ridgway, 1835.

- Benjamin W. Griffith, Jr., McIntosh and Weatherford Creek Indian Leaders. The University of Alabama Press, 2005 (Page 176)

- Hughes, Christine F.; Brodine, Charles E., eds. (2023). The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, Vol. 4. Washington: Naval Historical Center (GPO). ISBN 978-1-943604-36-4.

- Jones, K Randell (2006) In the Footsteps of Davy Crockett Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair. ISBN 0895873249

- Walter Lowrie & Walter S Franklin. American State Papers: Foreign Relations: Volume 4. Washington: Gales & Seaton, 1834 [2]

- John K. Mahon. History of the Second Seminole War. 2nd revised edition. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1985 (1967).

- Owsley, Frank L. & Smith, Gene A. (1997). Filibusters and Expansionists: Jeffersonian Manifest Destiny, 1800–1821. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0880-6

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars. Viking Penguin, 2001.

- Sugden, John (January 1982). "The Southern Indians in the War of 1812: The Closing Phase". Florida Historical Quarterly.

- Dale Cox & Rachel Conrad (2020), The Fort at Prospect Bluff, The British Post on the Apalachicola and the Battle of Negro Fort, Old Kitchen Media, ISBN 9780578634623.

Further reading

[edit]- Buck, Marcus C. (1836), Letter to his father, August 4, 1816, vol. 2, Army & Navy Chronicle, pp. 115–116

- Clinch, Lt. Col. 4th Inf. commanding, D.L. (1836), Letter to Col. R. Butler, August 2, 1816, vol. 2, Army & Navy Chronicle, pp. 114–115

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Skip Horack. The Eden Hunter, Counterpoint, 2010. (A novel inspired by the assault on the Negro Fort.)

External links

[edit]- The Secretary of War (John C. Calhoun) (February 2, 1819). "Letter from the Secretary of War, transmitting, pursuant to a Resolution of the House of Representatives, of the 26th Ult. Information in Relation to the Destruction of the Negro Fort of East Florida, in the Month of July, 1816, &c. &c". Washington DC. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution: With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons (1855) at archive.org

- Tragedy and Survival Virtual Reconstruction of the 1816 Fort

- Fort Gadsden - official site at Apalachicola National Forest, including a 3-minute video.

- Fort Gadsden and the "Negro Fort" at exploresouthernhistory.com.

- Map to Fort Gadsden

- Negro Fort, 8 Story Panels with Pictures narrating the attack on the fort in 1816, from the documentary site Rebellion: John Horse and the Black Seminoles

- Negro Fort at Ghost Towns

- Fort Gadsden at American Forts Network

- The First Emancipation Proclamation at Daily Kos

- National Historic Landmarks in Florida

- Black Seminoles

- Florida in the American Civil War

- American Civil War forts in Florida

- Seminole Wars

- 1816 in the Spanish Empire

- Former populated places in Florida

- 1810s in the United States

- History of slavery in Florida

- Protected areas of Franklin County, Florida

- British forts in the United States

- Colonial forts in Florida

- Apalachicola National Forest

- Former populated places in Franklin County, Florida

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Florida

- 1814 establishments in the British Empire

- National Register of Historic Places in Franklin County, Florida

- Maroons (people)

- American rebel slaves

- Spanish Florida

- Pre-emancipation African-American history

- African-American history of Florida

- Pre-statehood history of Florida

- Slave soldiers

- Underground Railroad locations

- Archaeological sites in Florida

- Demolished buildings and structures in Florida

- Trading posts in the United States

- African-American museums in Florida

- African-American military monuments and memorials

- Negro Fort

- Native American history of Florida