Folsom tradition

Map of Folsom tradition (modern shoreline shown) | |

| Geographical range | Great Plains |

|---|---|

| Period | Lithic or Paleo-Indian stage |

| Dates | c. 10800 – 10200 BCE[1] |

| Type site | Folsom site |

| Preceded by | Clovis culture |

The Folsom tradition is a Paleo-Indian archaeological culture that occupied much of central North America from c. 10800 BCE to c. 10200 BCE. The term was first used in 1927 by Jesse Dade Figgins, director of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.[2] The discovery by archaeologists of projectile points in association with the bones of extinct Bison antiquus, especially at the Folsom site near Folsom, New Mexico, established much greater antiquity for human residence in the Americas than the previous scholarly opinion that humans in the Americas dated back only 3,000 years. The findings at the Folsom site have been called the "discovery that changed American archaeology."[3]

Controversy

[edit]The antiquity of humans in the New World was a controversial topic in the late 19th and early 20th century. Beginning in 1859, discoveries of human bones in Europe in association with extinct Pleistocene mammals proved to scientists that human beings had existed further into the past than the Biblical tradition of a world created 6,000 years ago. Pioneering American archaeologists soon found evidence of early humans living in the Americas. In 1872, Charles Conrad Abbott announced the discovery of traces of human presence in the Delaware River Valley dating from the ice ages, Although many of his findings were later disproven, Abbott inspired a hunt for the remains of ancient man in the Americas.[4][5]

However, claims that humans may have inhabited the Americas thousands or tens of thousands of years ago were controversial. In the "Great Paleolithic War" proponents of recent and ancient peopling faced off in opposition to each other. In the early 1900s, Ales Hrdlicka and William Henry Holmes of the Smithsonian Institution became the chief advocates of the view that man had not lived in the Americas for longer than 3,000 years.[6][7] Hrdlicka and others made it "virtually taboo" for any archaeologist "desirous of a successful career" to advocate a deep antiquity for inhabitants of the Americas. The findings at the Folsom site eventually overturned that conventional wisdom.[8]

Discovery of Folsom

[edit]On August 27, 1908, 15 in (380 mm) of rain fell on Johnson Mesa in New Mexico causing downstream floods along the Dry Cimarron River. A local African-American cowboy, George McJunkin, surveyed the damage in Wild Horse Arroyo and found bones uncovered by the flood. He recognized the bones as similar to but larger than bison bones and among the bones he found projectile points. McJunkin tried to interest amateur palentologists from Raton, New Mexico, to visit the isolated site but he died in 1922 with the Folsom site still unvisited by scientists.[9][10]

Archaeologists had made earlier and similar discoveries. In 1895, at the 12 Mile Creek site in western Kansas, an archaeologist found a projectile point in conjunction with the bones of extinct bison.[11] At Vero Beach, Florida in 1916, an archaeologist found human bones and the bones of extinct mammals mixed together. Additional findings of human bones mixed with those of extinct mammals were found in Nebraska and Kansas. Hrdlicka discounted all of the findings based on his belief that the human remnants were too modern in appearance to belong to older human beings. In 1922, shortly after McJunkin's death, a Raton blacksmith, Carl Schwachheim, and a banker, Fred Howarth, both amateur naturalists visited the Folsom site. They collected bones and took them to Jesse Figgins, director of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science and palaentologist Harold Cook. Figgins and Cook identified the bones as belonging to an extinct species of bison, Bison antiquus. In 1926, all four men visited the Folsom site and began excavations.[12]

By the time they excavated Folsom, Figgins and Cook were already persuaded of the antiquity of humans in the New World. In 1922, Cook had found a human tooth among the bones of extinct mammals at Snake Creek in Nebraska. In 1924, at Lone Wolf Creek in Texas, excavators reported to Figgins that they found three projectile points associated with a bison skeleton. The excavators at Folsom found several projectile points at the site and on August 29, 1927, Schwachheim found the proof they had been seeking: a spear point clearly associated with the bones of the extinct Bison antiquus (10 to 25 percent larger than now-existent Bison bison). Other archaeologists were invited to see the findings in situ and they agreed that the bison bones and the spear point were contemporaneous. As the date of the extinction of the ancient bison had not yet been determined, archaeologists at a meeting of the American Anthropological Association in December 1927 speculated that man had arrived in the New World 15 to 20 thousand years ago. Hrdlička, however, was not persuaded and along with a few others ignored the Folsom evidence,[13] but after the Folsom discovery archaeologists mostly believed that humans resided in the Americas long before Hrdliča's 3,000 year claim. Speculation about the exact antiquity of Folsom continued until radiocarbon dating came into use in the 1950s and the bison bones at the site could be dated more precisely.[14]

Figgins and Cook paid a price for their challenge to the scientific establishment. Neither of them were invited to any of the seven academic symposia devoted to American antiquity which took place from 1927 to 1937.[15]

Folsom culture

[edit]

The Folsom Complex dates to a few hundred years between 11,000 BCE and 10,000 BCE (older uncalibrated radiocarbon dating had estimated the age of Folsom between 9,000 and 8,000 BCE.[16]) and archaeologists believe it evolved from the earlier Clovis culture.[17] Bayesian statistical analysis of radiocarbon dates found that the earliest Folsom dates overlap with the latest Clovis dates, indicating that the two technologies overlapped for multiple generations and supporting the idea that Folsom represents a technological innovation within Clovis.[18] There is a possible correlation, but not necessarily a causation, between the end of Clovis and the onset of Folsom with the extinction of most species of megafauna.[19] Artifacts from the Clovis culture are associated with the bones of mammoths; archaeologists have not found evidence of mammoths being a prey of Folsom hunters. In addition, the Bison antiquus, the most important prey animal of the Folsom hunters, became extinct about the same time that Folsom evolved into cultures relying on greater dependence on smaller animals and plant foods.[20] Authorities differ as to whether the extinctions of megafauna were caused by climate change (the Younger Dryas) or over-hunting by Paleo Indians or both.[21]

The Folsom culture flourished over a large area on the Great Plains of the United States and Canada, eastward as far as Illinois and westward into the Rocky Mountains. One Folsom site is in Mexico across the Rio Grande River from El Paso, Texas. The distinguishing feature of Folsom culture was its projectile points for spears. The bow and arrow was not yet in use. Folsom points were smaller and more delicate than the projectile points made by the preceding Clovis culture. The points were painstakingly crafted of flint. Folsom projectile points were often made from sources of flint hundreds of miles distant from where they have been found. Folsom flint knappers used the highest quality of flint. Folsom points are distinguished by "fluting" which is flaking away a groove running down the center of the projectile point from one end to the other. Fluting a point was difficult for the craftsman and the attempt often resulted in failure as demonstrated by findings of many ruined projectile points. Folsom people also produced large quantities of flint knives, scrapers, and other stone and bone tools.[22]

The quality of stone used, the non-utility of fluting except for its aesthetic appeal, and the emphasis on color in selecting flint for making points may indicate a ritual or religious aspect in the production and use of Folsom points, possibly to ensure success in the hunt.[23][24]

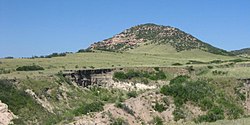

In addition to individual kills, a practice of Folsom hunters was to ambush groups of bison by driving them into narrow ravines and gullies where they could be slaughtered. Kill sites have been found with the bones of five to 55 bison. Archaeologists have also found bones of animals other than bison in association with the Folsom remains. The sparse remains of Folsom settlements are usually found near kill sites and steams or springs where bison and other animals congregated. Folsom settlements were small, comprising perhaps on average five families numbering 25 or more people. Several groups may have joined together for communal bison hunts.[23]

See also

[edit]- Dalton tradition – late Paleo-Indian and Early Archaic projectile point tradition

Additional Folsom sites

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Surovell, Todd; Hodgins, Gregory; Boyd, Joshua; Haynes, C. Vance Jr. (April 2016). "On the Dating of the Folsom Complex and its Correlation with the Younger Dryas, the End of Clovis, and Megafaunal Extinction". PaleoAmerica. 2 (2): 7. doi:10.1080/20555563.2016.1174559. S2CID 45884830. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Hillerman, Anthony G. (1973). "The Hunt for the Lost American". The Great Taos Bank Robbery and Other Indian Country Affairs. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0306-4. republished in The Great Taos Bank Robbery and Other Indian Country Affairs. New York: Harper Paperbacks. May 1997. ISBN 0-06-101173-8.

- ^ Peeples, Matt. "George McJunkin and the Discovery that Changed American Archaeology". Archaeology Southwest. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Charles C. Mann. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf (2005) ISBN 1-4000-3205-9. pages 160–163.

- ^ Herman, G. C. "Abbott Farm Hunter Research, Chapter 5: Archaeological History" (PDF). Impact Tectonics. pp. 5-1 to 5-10. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 0-19-507618-4.

- ^ Hillerman, Tony (Winter 1971). "The Czech that Bounced" (PDF). New Mexico. 50 (1, 2): 26–27.

- ^ Meltzer, David J. (Winter 2005). "The Seventy-Year Itch: Controversies over Human Antiquity and Their Resolution". Journal of Anthropological Research. 61 (4): 435–439. doi:10.3998/jar.0521004.0061.401. JSTOR 3631536. S2CID 162069721.

- ^ Meltzer 2005, p. 437.

- ^ Ramirez Mather, Jeanne. "George McJunkin" (PDF). Classroom Spice. University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Hill, Jr., Matthew E. (May 2006). "Before Folsom: The 12 Mile Creek Site and the Debate Over Peopling of the Americas". Plains Anthropologist. 51 (198): 141–143. doi:10.1179/pan.2006.011. JSTOR 25670870. S2CID 218669497. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Meltzer, David J. (2006). Folsom. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 22–29. ISBN 0-520-24644-6. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Meltzer 2006, pp. 33–39.

- ^ Meltzer, David J.; Todd, Lawrence C.; Holliday, Vance T. (January 2002). "The Folsom (Paleoindian) Type Site: Past Investigations, Current Studies". American Antiquity. 67 (1): 5. doi:10.2307/2694875. JSTOR 2694875. S2CID 164147120.

- ^ Meltzer 2005, p. 457.

- ^ "Folsom complex | ancient North American culture | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-03-05.

- ^ "Folsom Period". www.umanitoba.ca. Retrieved 2022-03-05.

- ^ Buchanan, Briggs; Kilby, J. David; LaBelle, Jason M.; Surovell, Todd A.; Holland-Lulewicz, Jacob; Hamilton, Marcus J. (July 2022). "Bayesian Modeling of the Clovis and Folsom Radiocarbon Records Indicates a 200-Year Multigenerational Transition". American Antiquity. 87 (3): 567–580. doi:10.1017/aaq.2021.153. ISSN 0002-7316.

- ^ Surovell et al. 2016, pp. 1–7.

- ^ Frison, George C. (1998). "Paleoindian large mammal hunters on the plains of North America". PNAS. 95 (24): 14576–14582. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9514576F. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14576. PMC 24415. PMID 9826742.

- ^ Barnosky, Anthony D. (1 October 2004). "Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents". Science. 306 (5693): 70–75. Bibcode:2004Sci...306...70B. doi:10.1126/science.1101476. JSTOR 3839254. PMID 15459379. S2CID 36156087.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Leslie (October 2004). "The Folsom Culture" (PDF). Central States Archaeological Journal. 51 (4): 173. JSTOR 43142386.

- ^ a b Pfeiffer 2004, p. 173.

- ^ Butkus, Edmund A. (July 2004). "How Extensive was the Folsom Tradition in North America". Central States Archaeology Journal. 51 (3): 172–173. JSTOR 4314386. Note: JSTOR web address mistaken in April 2023, search author's name and article title for access.

- Archaeology of Canada

- Archaeology of the United States

- Archaeological cultures of North America

- Hunter-gatherers of the United States

- Hunter-gatherers of Canada

- Native American history of Colorado

- Paleo-Indian period

- Pre-Columbian cultures

- Prehistoric cultures in Colorado

- 11th millennium BC

- 1926 archaeological discoveries

- Upper Paleolithic cultures

- 1908 archaeological discoveries