Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS[1] or PFASs[2]) are a group of synthetic organofluorine chemical compounds that have multiple fluorine atoms attached to an alkyl chain; there are 7 million such chemicals according to PubChem.[3] PFAS came into use after the invention of Teflon in 1938 to make fluoropolymer coatings and products that resist heat, oil, stains, grease, and water. They are now used in products including waterproof fabric such as Nylon, yoga pants, carpets, shampoo, feminine hygiene products, mobile phone screens, wall paint, furniture, adhesives, food packaging, heat-resistant non-stick cooking surfaces such as Teflon,[4] firefighting foam, and the insulation of electrical wire.[5][6][7] PFAS are also used by the cosmetic industry in most cosmetics and personal care products, including lipstick, eye liner, mascara, foundation, concealer, lip balm, blush, and nail polish.[8][9]

Many PFAS such as PFOS and PFOA pose health and environmental concerns because they are persistent organic pollutants; they were branded as "forever chemicals" in an article in The Washington Post in 2018.[10] Some have half-lives of over eight years due to a carbon-fluorine bond, one of the strongest in organic chemistry.[11][12][13][14][15] They move through soils and bioaccumulate in fish and wildlife, which are then eaten by humans. Residues are now commonly found in rain and drinking water.[11][16][17][6] Since PFAS compounds are highly mobile, they are readily absorbed through human skin and through tear ducts, and such products on lips are often unwittingly ingested.[18] Due to the large number of PFAS, it is challenging to study and assess the potential human health and environmental risks; more research is necessary and is ongoing.[19][11][20][5]

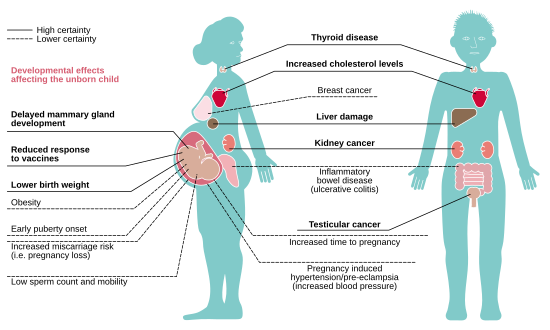

Exposure to PFAS, some of which have been classified as carcinogenic and/or as endocrine disruptors, has been linked to cancers such as kidney, prostate and testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, suboptimal antibody response / decreased immunity, decreased fertility, hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, reduced infant and fetal growth and developmental issues in children, obesity, dyslipidemia (abnormally high cholesterol), and higher rates of hormone interference.[5][21][22]

The use of PFAS has been regulated internationally by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants since 2009, with some jurisdictions, such as China and the European Union, planning further reductions and phase-outs. However, major producers and users such as the United States, Israel, and Malaysia have not ratified the agreement and the chemical industry has lobbied governments to reduce regulations[23] or has moved production to countries such as Thailand, where there is less regulation.[24][25] In the United States, the Republican Party has filibustered bills regulating the chemicals.[23] Cover-ups and the suppression of studies in 2018 by the Trump administration led to bipartisan outrage.[26][27]

The market for PFAS was estimated to be $28 billion in 2023 and the majority are produced by 12 companies: 3M, AGC Inc., Archroma, Arkema, BASF, Bayer, Chemours, Daikin, Honeywell, Merck Group, Shandong Dongyue Chemical, and Solvay.[28] Sales of PFAS, which cost approximately $20 per kilogram, generate a total industry profit of $4 billion per year on 16% profit margins.[29] Due to health concerns, several companies have ended or plan to end the sale of PFAS or products that contain them; these include W. L. Gore & Associates (the maker of Gore-Tex), H&M, Patagonia, REI, and 3M.[30][31][32][33][34][35] PFAS producers have paid billions of dollars to settle litigation claims, the largest being a $10.3 billion settlement paid by 3M for water contamination in 2023.[36] Studies have shown that companies have known of the health dangers since the 1970s – DuPont and 3M were aware that PFAS was "highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when ingested".[37] External costs, including those associated with remediation of PFAS from soil and water contamination, treatment of related diseases, and monitoring of PFAS pollution, may be as high as US$17.5 trillion annually, according to ChemSec.[29] The Nordic Council of Ministers estimated health costs to be at least €52–84 billion in the European Economic Area.[38] In the United States, PFAS-attributable disease costs are estimated to be US$6–62 billion.[39][40]

Definition

[edit]

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are a group of synthetic organofluorine chemical compounds that have multiple fluorine atoms attached to an alkyl chain. Different organizations use different definitions for PFAS, leading to estimates of between 8,000 and 7 million chemicals within the group. The EPA toxicity database, DSSTox, lists 14,735 unique PFAS chemical compounds.[41][42]

An early definition required that they contain at least one perfluoroalkyl moiety, −CnF2n+1.[12] Beginning in 2021, the OECD expanded its terminology, stating that "PFAS are defined as fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I atom attached to it), i.e., with a few noted exceptions, any chemical with at least a perfluorinated methyl group (−CF3) or a perfluorinated methylene group (−CF2−) is a PFAS."[2][43] This definition notably includes Carbon tetrafluoride.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines PFAS in the Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List 5 as substances that contain "at least one of the following three structures: R−CF2−CF(R')R", where both the −CF2− and −CF− moieties are saturated carbons, and none of the R groups can be hydrogen; R−CF2−O−CF2−(R'), where both the −CF2− moieties are saturated carbons, and none of the R groups can be hydrogen; or CF3−C−(CF3)RR', where all the carbons are saturated, and none of the R groups can be hydrogen.[44]

A summary table of some PFAS definitions is provided in Hammel et al (2022).[45]

Fluorosurfactants

[edit]

Fluorinated surfactants or fluorosurfactants are a subgroup of PFAS characterized by a hydrophobic fluorinated "tail" and a hydrophilic "head" that behave as surfactants. These are more effective at reducing the surface tension of water than comparable hydrocarbon surfactants.[46] They include the perfluorosulfonic acids, such as perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), and the perfluorocarboxylic acids like perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

As with other surfactants, fluorosurfactants tend to concentrate at the phase interfaces.[47] Fluorocarbons are both lipophobic and hydrophobic, repelling both oil and water. Their lipophobicity results from the relative lack of London dispersion forces compared to hydrocarbons, a consequence of fluorine's large electronegativity and small bond length, which reduce the polarizability of the surfactants' fluorinated molecular surface. Fluorosurfactants are more stable than hydrocarbon surfactants due to the stability of the carbon–fluorine bond. Perfluorinated surfactants persist in the environment for the same reason.[16]

Fluorosurfactants such as PFOS, PFOA, and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) have caught the attention of regulatory agencies because of their persistence, toxicity, and widespread occurrence in the blood of general populations.[48][49]

PFASs are used in emulsion polymerization to produce fluoropolymers, used in stain repellents, polishes, paints, and coatings.[50]

Health and environmental effects

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

PFASs were originally considered to be chemically inert.[51][52] Early occupational studies revealed elevated levels of fluorochemicals, including perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA, C8), in the blood of exposed industrial workers, but cited no ill health effects.[53][54] These results were consistent with the measured serum concentrations of PFOS and PFOA in 3M plant workers ranging from 0.04 to 10.06 ppm and 0.01 to 12.70 ppm, respectively, well below toxic and carcinogenic levels cited in animal studies.[54] Given, however, the serum elimination half-life of four to five years and widespread environmental contamination, molecules have been shown to accumulate in humans sufficiently to cause adverse health outcomes.[51]

Prevalence in rain, soil, water bodies, and air

[edit]In 2022, levels of at least four perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in rain water worldwide greatly exceeded the EPA's lifetime drinking water health advisories as well as comparable Danish, Dutch, and European Union safety standards, leading to the conclusion that "the global spread of these four PFAAs in the atmosphere has led to the planetary boundary for chemical pollution being exceeded".[57]

It had been thought that PFAAs would eventually end up in the oceans, where they would be diluted over decades, but a field study published in 2021 by researchers at Stockholm University found that they are often transferred from water to air when waves reach land, are a significant source of air pollution, and eventually get into rain. The researchers concluded that pollution may impact large areas.[58][59][60]

In 2024, a worldwide study of 45,000 groundwater samples found that 31% of samples contained levels of PFAS that were harmful to human health; these samples were taken from areas not near any obvious source of contamination.[61]

Soil is also contaminated and the chemicals have been found in remote areas such as Antarctica.[62] Soil contamination can result in higher levels of PFAs found in foods such as white rice, coffee, and animals reared on contaminated ground.[63][64][65]

Adverse health outcomes

[edit]From 2005 to 2013, three epidemiologists known as the C8 Science Panel conducted health studies in the Mid-Ohio Valley as part of a contingency to a class action lawsuit brought by communities in the Ohio River Valley against DuPont in response to landfill and wastewater dumping of PFAS-laden material from DuPont's West Virginia Washington Works plant.[66] The panel measured PFOA (also known as C8) serum concentrations in 69,000 individuals from around DuPont's Washington Works Plant and found a mean concentration of 83 ng/mL, compared to 4 ng/mL in a standard population of Americans.[67] This panel reported probable links between elevated PFOA blood concentration and hypercholesterolemia, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular cancer, kidney cancer as well as pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia.[68][69][70][71][72]

The severity of PFAS-associated health effects can vary based on the length of exposure, level of exposure, and health status.[73]

Pregnancy issues

[edit]Exposure to PFAS is a risk factor for various hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, including preeclampsia and high blood pressure. It is not clear whether PFAS exposure is associated with wider cardiovascular disorders during pregnancy.[74] Human breast milk can harbor PFASs, which can be transferred from mother to infant via breastfeeding.[75][64]

Fertility issues

[edit]Endocrine disruptors, including PFASs, are linked with the male infertility crisis.[76]

A report in 2023 by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai linked high exposure to PFAS with a 40% decrease in the ability for a woman to have a successful pregnancy as well as hormone disruption and delayed puberty onset.[77][78]

Liver issues

[edit]A meta-analysis for associations between PFASs and human clinical biomarkers for liver injury, analyzing PFAS effects on liver biomarkers and histological data from rodent experimental studies, concluded that evidence exists that PFOA, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) caused hepatotoxicity in humans.[79]

Cancer

[edit]PFOA is classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) based on "sufficient" evidence for cancer in animals and "strong" mechanistic evidence in exposed humans. IARC also classified PFOS as possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2b) based on "strong" mechanistic evidence.[22] There is a lack of high-quality epidemiological data on the associations between many specific PFAS chemicals and specific cancer types, and research is ongoing.[80]

Hypercholesterolemia

[edit]A response is observed in humans where elevated PFOS levels were significantly associated with elevated total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, highlighting significantly reduced PPAR expression and alluding to PPAR independent pathways predominating over lipid metabolism in humans compared to rodents.[81]

Ulcerative colitis

[edit]PFOA and PFOS have been shown to significantly alter immune and inflammatory responses in human and animal species. In particular, IgA, IgE (in females only) and C-reactive protein have been shown to decrease whereas antinuclear antibodies increase as PFOA serum concentrations increase.[82] These cytokine variations allude to immune response aberrations resulting in autoimmunity. One proposed mechanism is a shift towards anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages and/or T-helper (TH2) response in intestinal epithelial tissue which allows sulfate-reducing bacteria to flourish. Elevated levels of hydrogen sulfide result, which reduce beta-oxidation and nutrient production, leading to a breakdown of the colonic epithelial barrier.[83]

Thyroid disease

[edit]Hypothyroidism is the most common thyroid abnormality associated with PFAS exposure.[84] PFASs have been shown to decrease thyroid peroxidase, resulting in decreased production and activation of thyroid hormones in vivo.[85] Other proposed mechanisms include alterations in thyroid hormone signaling, metabolism and excretion as well as function of nuclear hormone receptor.[84]

Bioaccumulation and biomagnification

[edit]

- In marine species of the food web

Bioaccumulation controls internal concentrations of pollutants, including PFAS, in individual organisms. When bioaccumulation is looked at in the perspective of the entire food web, it is called biomagnification, which is important to track because lower concentrations of pollutants in environmental matrices such as seawater or sediments, can very quickly grow to harmful concentrations in organisms at higher trophic levels, including humans. Notably, concentrations in biota can even be greater than 5000 times those present in water for PFOS and C10–C14 PFCAs.[86] PFAS can enter an organism by ingestion of sediment, through the water, or directly via their diet. It accumulates namely in areas with high protein content, in the blood and liver, but it is also found to a lesser extent in tissues.[87]

Biomagnification can be described using the estimation of the trophic magnification factor (TMF), which describes the relationship between the contamination levels in a species and their trophic level in the food web. TMFs are determined by graphing the log-transformed concentrations of PFAS against the assigned trophic level and taking the antilog of the regression slope (10slope).[16]

In a study done on a macrotidal estuary in Gironde, SW France, TMFs exceeded one for nearly all 19 PFAS compounds considered in the study and were particularly high for PFOA and PFNA (6.0 and 3.1 respectively).[16] A TMF greater than one signifies that accumulation in the organism is greater than that of the medium, with the medium being seawater in this case.

PFOS, a long-chain sulfonic acid, was found at the highest concentrations relative to other PFASs measured in fish and birds in northern seas such as the Barents Sea and the Canadian Arctic.[88]

A study published in 2023 analyzing 500 composite samples of fish fillets collected across the United States from 2013 to 2015 under the EPA's monitoring programs showed freshwater fish ubiquitously contain high levels of harmful PFAS, with a single serving typically significantly increasing the blood PFOS level.[89][90]

Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of PFASs in marine species throughout the food web, particularly frequently consumed fish and shellfish, can have important impacts on human populations.[91] PFASs have been frequently documented in both fish and shellfish that are commonly consumed by human populations,[92] which poses health risks to humans and studies on the bioaccumulation in certain species are important to determine daily tolerable limits for human consumption, and where those limits may be exceeded causing potential health risks.[93] This has particular implications for populations that consume larger numbers of wild fish and shellfish species.[92] PFAS contamination has also resulted in disruptions to the food supply, such as closures and limits on fishing.[94]

Fluorosurfactants with shorter carbon chains may be less prone to accumulating in mammals;[50] there is still some concern that they may be harmful to both humans[95][96][97] and the environment.[98][19]

Suppression of information on health effects

[edit]Since the 1970s, DuPont and 3M were aware that PFAS was "highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when ingested".[37] Producers used several strategies to influence science and regulation – most notably, suppressing unfavorable research and distorting public discourse.[37]

In 2018, under the Presidency of Donald Trump, White House staff and the United States Environmental Protection Agency pressured the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry to suppress a study that showed PFASs to be even more dangerous than previously thought.[26][27]

Concerns, litigation, and regulations in specific countries and regions

[edit]Arctic

[edit]In 2024, research at McGill University in Quebec,[99] indicated that PFASs were being brought to the Arctic from polluted southern waters by migrating birds.[100] Although it is much less than compared to the introduction by wind and the oceans, the birds become vectors, transmitting the toxic chemicals. Rainer Lohmann, an oceanographer at the University of Rhode Island, noted that this has a significant localized affect that is devastating for Arctic predators who accumulate toxins in their bodies because the contaminants from the birds often enter the food chain directly since the birds are the prey of many species.

Australia

[edit]In 2017, the ABC's current affairs program Four Corners reported that the storage and use of firefighting foams containing perfluorinated surfactants at Australian Defence Force facilities around Australia had contaminated nearby water resources.[101] In 2019, remediation efforts at RAAF Base Tindal and the adjacent town of Katherine were ongoing.[102] In the 2022 Australian federal budget $428 million was allocated for works at HMAS Albatross, RAAF Base Amberley, RAAF Base Pearce and RAAF Base Richmond including funding to remediate PFAS contamination.[103]

Canada

[edit]Although PFASs are not manufactured in Canada, they may be present in imported goods and products. In 2008, products containing PFOS as well as PFOA were banned in Canada, with exceptions for products used in firefighting, the military, and some forms of ink and photo media.[104]

Health Canada has published drinking water guidelines for maximum concentrations of PFOS and PFOA to protect the health of Canadians, including children, over a lifetime's exposure to these substances. The maximum allowable concentration for PFOS under the guidelines is 0.0002 milligrams per liter. The maximum allowable concentration for PFOA is 0.0006 milligrams per liter.[105] In August 2024, Health Canada established an objective of 30 ng/L for the sum of the concentration of 25 PFASs[106] detected in drinking water.[107]

New Zealand

[edit]The New Zealand Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has banned the use of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in cosmetic products starting from 31 December 2026. This will make the country one of the first in the world to take this step on PFAS to protect people and the environment.[108]

United Kingdom

[edit]The environmental consequences of PFAS, especially from firefighting activities, have been recognized since the mid-1990s and came to prominence after the Buncefield explosion on 11 December 2005. The Environment Agency has undertaken a series of projects to understand the scale and nature of PFAS in the environment. The Drinking Water Inspectorate requires water companies to report concentrations of 47 PFAS.[109]

European Union

[edit]Many PFASs are either not covered by European legislation or are excluded from registration obligations under the EU Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) chemical regulation.[110] Several PFASs have been detected in drinking water,[111] municipal wastewater,[112] and landfill leachates[113] worldwide.

In 2019, the European Council requested the European Commission to develop an action plan to eliminate all non-essential uses of PFAS due to the growing evidence of adverse effects caused by exposure to these substances; the evidence for the widespread occurrence of PFAS in water, soil, articles, and waste; and the threat it can pose to drinking water.[114] Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden submitted a so-called restriction proposal based on the REACH regulation to achieve a European ban on the production, use, sale and import of PFAS.[115] The proposal states that a ban is necessary for all use of PFAS, with different periods for different applications when the ban takes effect (immediately after the restriction comes into force, five years afterward, or 12 years afterward), depending on the function and the availability of alternatives. The proposal has not assessed the use of PFAS in medicines, plant protection products, and biocides because specific regulations apply to those substances (Biocidal Products Regulation, Plant Protection Products Regulation, Medicinal Products Regulation) that have an explicit authorization procedure that focuses on risk for health and the environment.

The proposal was submitted on 13 January 2023 and published by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) on 7 February. From 22 March to 21 September, citizens, companies, and other organizations commented on the proposal during a public consultation.[116] Based on the information in the restriction proposal and the consultation, two committees from ECHA formulate an opinion on the risk and socio-economic aspects of the proposed restriction. Within a year of publication, the opinions are sent to the European Commission, which makes a final proposal that is submitted to the EU Member States for discussion and decision.[117] Eighteen months after the publication of the restriction decision (which may differ from the original proposal), it will enter into force.[116]

Italy

[edit]127,000 residents in the Veneto region are estimated to have been exposed to contamination through tap water, and it is thought to be Europe's biggest PFAS-related environmental disaster.[20][118] While Italy's National Health Institute (ISS, Istituto Superiore di Sanità) set the threshold limit of PFOA in the bloodstream at 8 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL), some residents had reached 262 and some industrial employees reach 91,900 ng/mL. In 2021 some data was disclosed by Greenpeace and local citizens after a long legal battle against the Veneto Region and ISS, which for years has denied access to data, despite values known since or even before 2017. The Veneto region has not carried out further monitoring or taken resolutive actions to eliminate pollution and reduce, at least gradually, the contamination of non-potable water. Although in 2020 the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) has reduced by more than four times the maximum tolerable limit of PFAS that can be taken through the diet, the region has not carried out new assessments or implemented concrete actions to protect the population and the agri-food and livestock sectors. Some limits were added to monitoring the geographical area, which does not include the orange zone and other areas affected by contamination, as well as the insufficiency of analysis on important productions widespread in the areas concerned: eggs (up to 37,100 ng/kg), fish (18,600 ng/kg) spinach and radicchio (only one sampling carried out), kiwis, melons, watermelons, cereals (only one sample was analyzed), soy, wines and apples.[119]

Japan

[edit]A study of public water bodies ending in March 2022 showed that the sum of PFOS and PFOA concentrations exceeded 50 ng/L in 81 out of 1,133 test sites and in some cases are present at elevated levels in blood. This has led to pressure to increase regulations.[120]

Sweden

[edit]Highly contaminated drinking water has been detected at several locations in Sweden. Such locations include Arvidsjaur, Lulnäset, Uppsala and Visby.[121][122] In 2013, PFAS were detected at high concentrations in one of the two municipality drinking water treatment plants in the town of Ronneby, in southern Sweden. Concentrations of PFHxS and PFOS were found at 1700 ng/L and 8000 ng/L, respectively.[123] The source of contamination was later found to be a military fire-fighting exercise site in which PFAS containing fire-fighting foam had been used since the mid-1980s.[124]

Additionally, low-level contaminated drinking water has also been shown to be a significant exposure source of PFOA, PFNA, PFHxS and PFOS for Swedish adolescents (ages 10–21). Even though the median concentrations in the municipality drinking water were below one ng/L for each individual PFAS, positive associations were found between adolescent serum PFAS concentrations and PFAS concentrations in drinking water.[125]

United States

[edit]An estimated 26,000 U.S. sites are contaminated with PFASs.[126][127] More than 200 million Americans are estimated to live in places where the PFAS level in tap water, including PFOA and PFOS levels, exceeds the 1 ppt (part per trillion) limit set in 2022 by the EPA.[128]

Based on tap water studies from 716 locations from 2016 and 2021, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) found that the PFAS levels exceeded the EPA advisories in approximately 75% of the samples from urban areas and in approximately 25% of the rural area samples.[129]

Certain PFASs are no longer manufactured in the United States as a result of phase-outs including the PFOA Stewardship Program (2010–2015), in which eight major chemical manufacturers agreed to eliminate the use of PFOA and PFOA-related chemicals in their products and emissions from their facilities. However, they are still produced internationally and are imported into the U.S. in consumer goods.[130][131] Some types of PFAS are voluntarily not included in food packaging.[132]

In 2021, Senators Susan Collins of Maine and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut proposed the No PFAS in Cosmetics Act in the United States Senate.[133] It was also introduced in the United States House of Representatives by Michigan Representative Debbie Dingell,[134] but the Republican Party, supported by the U.S. chemical industry filibustered the bill.[23]

Military bases

[edit]The water in and around at least 126 U.S. military bases has been contaminated by high levels of PFASs because of their use of firefighting foams since the 1970s, according to a study by the U.S. Department of Defense. Of these, 90 bases reported PFAS contamination that had spread to drinking water or groundwater off the base.[135]

In 2022, a report by the Pentagon acknowledged that approximately 175,000 U.S. military personnel at two dozen American military facilities drank water contaminated by PFAS that exceeded the U.S. EPA limit. However, according to the Environmental Working Group, the Pentagon report downplayed the number of people exposed to PFAS, which was probably over 640,000 at 116 military facilities. The EWG found that the Pentagon also omitted from its report some types of diseases that are likely to be caused by PFAS exposure, such as testicular cancer, kidney disease, and fetal abnormalities.[136]

Environmental Protection Agency actions

[edit]The United States Environmental Protection Agency has published non-enforceable drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS.[137][138] In March 2021 EPA announced that it would develop national drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS.[139] Drinking water utilities are required to monitor PFAS levels and may receive subsidies to do so.[140][141] There are also regulations regarding wastewater (effluent guidelines) for industries that use PFASs in the manufacturing process as well as biosolids (processed wastewater sludge used as fertilizer).[142][143][144][145][146]

The EPA issued health advisories for four specific PFASs in June 2022, significantly lowering their safe threshold levels for drinking water. PFOA was reduced from 70 ppt to 0.004 ppt, while PFOS was reduced from 70 ppt to 0.02 ppt. A safe level for the compound GenX was set at 10 ppt, while that for PFBS was set at 2000 ppt. While not enforceable, these health advisories are intended to be acted on by states in setting their own drinking water standards.[147]

In August 2022, the EPA proposed to add PFOA and PFOS to its list of hazardous substances under the Superfund law.[148] EPA issued a final rule in April 2024, which requires that polluters pay for investigations and cleanup of these substances.[149][150]

In April 2024, the EPA issued a final drinking water rule for PFOA, PFOS, GenX, PFBS, PFNA, and PFHxS. Within three years, public water systems must remove these six PFAS to near-zero levels. States may be awarded grants up to $1 billion in aid to help with the initial testing and treatment of water for this purpose.[151][152][153][154][155]

Legal actions

[edit]In February 2017, DuPont and Chemours (a DuPont spin-off) agreed to pay $671 million to settle lawsuits arising from 3,550 personal injury claims related to the releasing of PFASs from their Parkersburg, West Virginia, plant into the drinking water of several thousand residents.[156] This was after a court-created independent scientific panel—the C8 Science Panel—found a "probable link" between C8 exposure and six illnesses: kidney and testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, pregnancy-induced hypertension and high cholesterol.[66]

In October 2018, a class action suit was filed by an Ohio firefighter against several producers of fluorosurfactants, including 3M and DuPont, on behalf of all U.S. residents who may have adverse health effects from exposure to PFASs.[157] The story is told in the film Dark Waters.[158]

In June 2023, 3M reached a US$10.3 billion settlement with several US public water providers to resolve water pollution claims tied to PFAS, while Chemours, DuPont and Corteva settled similar claims for $1.19 billion.[36]

In December 2023, as part of a four-year legal battle, the EPA banned Inhance, a Houston, Texas-based manufacturer that produces an estimated 200 million containers annually with a process that creates PFOA, from using the manufacturing process.[159][160] In March 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturned the ban. While the court did not deny the containers’ health risks, it said that the EPA could not regulate the manufactured containers under Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976, which only addresses "new" chemicals.[161]

State actions

[edit]In 2021, Maine became the first U.S. state to ban these compounds in all products by 2030, except for instances deemed "currently unavoidable".[162][163]

As of October 2020[update], the states of California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, and Wisconsin had enforceable drinking water standards for between two and six types of PFAS. The six chemicals (termed by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection as PFAS6) are measured either individually or summed as a group depending on the standard; they are:[164]

- Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)

- Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

- Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS)

- Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)

- Perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA)

- Perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA)

California

[edit]In 2021 California banned PFASs for use in food packaging and from infant and children's products and also required PFAS cookware in the state to carry a warning label.[165]

Maine

[edit]A program licensed and promoted by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection that provided free municipal wastewater sludge (biosolids) to farmers as fertilizer has resulted in PFAS contamination of local drinking water and farm-grown produce.[166][167]

Michigan

[edit]The Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART) was launched in 2017 and is the first multi-agency action team of its kind in the nation. Agencies representing health, environment, and other branches of state government have joined together to investigate sources and locations of PFAS contamination in the state, take action to protect people's drinking water, and keep the public informed. Groundwater is tested at locations throughout the state by various parties to ensure safety, compliance with regulations, and proactively detect and remedy potential problems. In 2010, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) discovered levels of PFASs in groundwater monitoring wells at the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base.[168] In 2024, citizen-led testing near the base in Oscoda discovered high levels of PFAS in foam along the shore of Lake Huron.[169] As additional information became available from other national testing, Michigan expanded its investigations into other locations where PFAS compounds were potentially used. In 2018, the MDEQ's Remediation and Redevelopment Division (RRD) established cleanup criteria for groundwater used as drinking water of 70 ppt of PFOA and PFOS, individually or combined. The RRD staff are responsible for implementing these criteria as part of their ongoing efforts to clean up sites of environmental contamination. The RRD staff are the lead investigators at most of the PFAS sites on the MPART website and also conduct interim response activities, such as coordinating bottled water or filter installations with local health departments at sites under investigation or with known PFAS concerns. Most of the groundwater sampling at PFAS sites under RRD's lead is conducted by contractors familiar with PFAS sampling techniques. The RRD also has a Geologic Services Unit, with staff who install monitoring wells and are also well versed with PFAS sampling techniques. The MDEQ has been conducting environmental clean-up of regulated contaminants for decades. Due to the evolving nature of PFAS regulations as new science becomes available, the RRD is evaluating the need for regular PFAS sampling at Superfund sites and is including an evaluation of PFAS sampling needs as part of a Baseline Environmental Assessment review. Earlier in 2018, the RRD purchased lab equipment that will allow the MDEQ Environmental Lab to conduct analyses of certain PFAS samples. (Currently, most samples are shipped to one of the few labs in the country that conduct PFAS analysis, in California, although private labs in other parts of the country, including Michigan, are starting to offer these services.) As of August 2018, RRD has hired additional staff to work on developing the methodology and conducting PFAS analyses.[170]

In 2020 Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel filed a lawsuit against 17 companies, including 3M, Chemours, and DuPont, for hiding known health and environmental risks from the state and its residents. Nessel's complaint identifies 37 sites with known contamination.[171] The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy introduced some of the strictest drinking water standards in the country for PFAS, setting maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for PFOA and PFOS to 8 and 16 ppt respectively (down from previous existing groundwater cleanup standards of 70 ppt for both), and introducing MCLs for five other previously unregulated PFAS compounds, limiting PFNA to six ppt, PFHxA to 400,000 ppt, PFHxS to 51 ppt, PFBS to 420 ppt and HFPO-DA to 370 ppt.[172] The change adds 38 additional sites to the state's list of known PFAS contaminated areas, bringing the total number of known sites to 137. About half of these sites are landfills and 13 are former plating facilities.[173]

In 2022 PFOS was found in beef produced at a Michigan farm: the cattle had been fed crops fertilized with contaminated biosolids. State agencies issued a consumption advisory, but did not order a recall, because there currently is no PFOS contamination in beef government standards.[174]

A 2024 study found that "atmospheric deposition could be a significant environmental pathway, particularly for the Great Lakes."[175][176]

Minnesota

[edit]In February 2018, 3M settled a lawsuit for $850 million related to contaminated drinking water in Minnesota.[177]

New Jersey

[edit]In 2018 the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) published a drinking water standard for PFNA. Public water systems in New Jersey are required to meet an MCL standard of 13 ppt.[178][179] In 2020 the state set a PFOA standard at 14 ppt and a PFOS standard at 13 ppt.[180]

In 2019 NJDEP filed lawsuits against the owners of two plants that had manufactured PFASs, and two plants that were cited for water pollution from other chemicals. The companies cited are DuPont, Chemours, and 3M.[181] NJDEP also declared five companies to be financially responsible for statewide remediation of the chemicals. Among the companies accused were Arkema and Solvay regarding a West Deptford Facility in Gloucester County, where Arkema manufactured PFASs, but Solvay claims to have never manufactured but only handled PFASs.[182] The companies denied liability and contested the directive.[183] In June 2020, the EPA and New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection published a paper reporting that a unique family of PFAS used by Solvay, chloroperfluoropolyether carboxylates (ClPFPECAs), were contaminating the soils of New Jersey as far from the Solvay facility as 150 km.[184] and the ClPFPECAs were found in water as well.[185]

Later in 2020, the New Jersey state attorney general filed suit in the New Jersey Superior Court against Solvay regarding PFAS contamination of the state's environment.[186] In May 2021, Solvay issued a press release that the company is "discontinuing the use of fluorosurfactants in the U.S.".[187]

New York

[edit]In 2016, New York, along with Vermont and New Hampshire, acknowledged PFOA contamination by requesting the EPA to release water quality guidance measures. Contamination has been observed by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation in Hoosick Falls, Newburgh, Petersburgh, Poestenkill, Mahopac, and Armonk.[188]

After a class action lawsuit, in 2021, the village of Hoosick Falls received a $65.25 million settlement from Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics, Honeywell, 3M, and DuPont due to the disposal of PFAS chemicals into the groundwater of the local water treatment plant.[189]

Washington

[edit]Five military installations in Washington State have been identified by the United States Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works as having PFAS contamination.[190] Toward environmental and consumer protections, the Washington State Department of Ecology published a Chemical Action Plan in November 2021, and in June 2022 the governor tasked the Washington State Department of Ecology with phasing out manufacture and import of products containing PFASs. Initial steps taken by the Washington State Department of Health to protect the public from exposure through drinking water have included setting State Action Levels for five PFASs (PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, and PFBS), which were implemented in November 2021.[191][192][193]

United Nations

[edit]In 2009, PFOS, its salts, and perfluorooctanesulfonyl fluoride, as well as PFOA and PFHxS, were listed as persistent organic pollutants under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants due to their ubiquitous, persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic nature.[194][195] The convention has been ratified by 186 jurisdictions, but has most notably not been ratified by the United States, Israel, and Malaysia.[196] The long-chain (C9–C21) PFCAs are currently under review for listing.[197]

Occupational exposure

[edit]Occupational exposure to PFASs occurs in numerous industries due to the widespread use of the chemicals in products and as an element of industrial process streams.[73] PFASs are used in more than 200 different ways in industries as diverse as electronics and equipment manufacturing, plastic and rubber production, food and textile production, and building and construction.[198] Occupational exposure to PFASs can occur at fluorochemical facilities that produce them and other manufacturing facilities that use them for industrial processing like the chrome plating industry.[73] Workers who handle PFAS-containing products can also be exposed during their work, such as people who install PFAS-containing carpets and leather furniture with PFAS coatings, professional ski-waxers using PFAS-based waxes, and fire-fighters using PFAS-containing foam and wear flame-resistant protective gear made with PFASs.[73][199][200]

Exposure pathways

[edit]People who are exposed to PFASs through their jobs typically have higher levels of PFASs in their blood than the general population.[73][201][202] While the general population is exposed to PFASs through ingested food and water, occupational exposure includes accidental ingestion, inhalation exposure, and skin contact in settings where PFAS become volatile.[203][12]

Professional ski wax technicians

[edit]Compared to the general public exposed to contaminated drinking water, professional ski wax technicians are more strongly exposed to PFASs (PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFHpA, PFDoDA) from the glide wax used to coat the bottom of skis to reduce the friction between the skis and snow.[204] During the coating process, the wax is heated, which releases fumes and airborne particles.[204] Compared to all other reported occupational and residential exposures, ski waxing had the highest total PFAS air concentrations.[205]

Manufacturing workers

[edit]People who work at fluorochemical production plants and in manufacturing industries that use PFASs in the industrial process can be exposed to PFASs in the workplace. Much of what we know about PFAS exposure and health effects began with medical surveillance studies of workers exposed to PFASs at fluorochemical production facilities. These studies began in the 1940s and were conducted primarily at U.S. and European manufacturing sites. Between the 1940s and 2000s, thousands of workers exposed to PFASs participated in research studies that advanced scientific understanding of exposure pathways, toxicokinetic properties, and adverse health effects associated with exposure.[53][206][207]

The first research study to report elevated organic fluorine levels in the blood of fluorochemical workers was published in 1980.[53] It established inhalation as a potential route of occupational PFAS exposure by reporting measurable levels of organic fluorine in air samples at the facility.[53] Workers at fluorochemical production facilities have higher levels of PFOA and PFOS in their blood than the general population. Serum PFOA levels in fluorochemical workers are generally below 20,000 ng/mL but have been reported as high as 100,000 ng/mL, whereas the mean PFOA concentration among non-occupationally exposed cohorts in the same time frame was 4.9 ng/mL.[208][54] Among fluorochemical workers, those with direct contact with PFASs have higher PFAS concentrations in their blood than those with intermittent contact or no direct PFAS contact.[206][208] Blood PFAS levels have been shown to decline when direct contact ceases.[208][209] PFOA and PFOS levels have declined in U.S. and European fluorochemical workers due to improved facilities, increased usage of personal protective equipment, and the discontinuation of these chemicals from production.[206][210] Occupational exposure to PFASs in manufacturing continues to be an active area of study in China with numerous investigations linking worker exposure to various PFASs.[211][212][213]

Firefighters

[edit]

PFASs are commonly used in Class B firefighting foams due to their hydrophobic and lipophobic properties, as well as the stability of the chemicals when exposed to high heat.[214]

Research into occupational exposure for firefighters is emergent, though frequently limited by underpowered study designs. A 2011 cross-sectional analysis of the C8 Health Studies found higher levels of PFHxS in firefighters compared to the sample group of the region, with other PFASs at elevated levels, without reaching statistical significance.[215] A 2014 study in Finland studying eight firefighters over three training sessions observed select PFASs (PFHxS and PFNA) increase in blood samples following each training event.[214] Due to this small sample size, a test of significance was not conducted. A 2015 cross-sectional study conducted in Australia found that PFOS and PFHxS accumulation was positively associated with years of occupational AFFF exposure through firefighting.[201]

Due to their use in training and testing, studies indicate occupational risk for military members and firefighters, as higher levels of PFASs exposure were indicated in military members and firefighters when compared to the general population.[216] PFAS exposure is prevalent among firefighters not only due to its use in emergencies but also because it is used in personal protective equipment. In support of these findings, states like Washington and Colorado have moved to restrict and penalize the use of Class B firefighting foam for firefighter training and testing.[217][218]

Exposure after September 11 attacks

[edit]The September 11 attacks and resulting fires caused the release of toxic chemicals used in materials such as stain-resistant coatings.[219] First responders to this incident were exposed to PFOA, PFNA, and PFHxS through inhalation of dust and smoke released during and after the collapse of the World Trade Center.[219]

Fire responders who were working at or near ground zero were assessed for respiratory and other health effects from exposure to emissions at the World Trade Center. Early clinical testing showed a high prevalence of respiratory health effects. Early symptoms of exposure often presented with persistent coughing and wheezing. PFOA and PFHxS levels were present in both smoke and dust exposure, but first responders exposed to smoke had higher concentrations of PFOA and PFHxS than those exposed to dust.[219]

Mitigation measures

[edit]Several strategies have been proposed as a way to protect those who are at greatest risk of occupational exposure to PFAS, including exposure monitoring, regular blood testing, and the use of PFAS-free alternatives such as fluorine-free firefighting foam and plant-based ski wax.[220]

Food and consumer goods

[edit]PFASs were found in many plant-based straws, such as paper straws.[221][222]

Remediation

[edit]Water treatment

[edit]Several technologies are currently available for remediating PFASs in liquids. These technologies can be applied to drinking water supplies, groundwater, industrial wastewater, surface water, and other applications such as landfill leachate. Influent concentrations of PFASs can vary by orders of magnitude for specific media or applications. These influent values, along with other general water quality parameters (for example, pH) can influence the performance and operating costs of the treatment technologies. The technologies are:

- Photodegradation[223]

- Foam fractionation[224]

- Sorption

- Granular activated carbon

- Biochar

- Ion exchange

- Precipitation/flocculation/coagulation

- Redox manipulation (chemical oxidation and reduction technologies)

- Membrane filtration

- Reverse osmosis

- Nanofiltration[225]

- Supercritical water oxidation[226]

- Low Energy Electrochemical Oxidation (EOx)

Private and public sector applications of one or more of these methodologies above are being applied to remediation sites throughout the United States and other international locations.[227] Most solutions involve on-site treatment systems, while others are leveraging off-site infrastructure and facilities, such as a centralized waste treatment facility, to treat and dispose of the PFAS pool of compounds.

The US-based Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council (ITRC) has undertaken an extensive evaluation of ex-situ and in-situ treatment technologies for PFAS-impacted liquid matrices. These technologies are divided into field-implemented technologies, limited application technologies, and developing technologies and typically fit into one of three technology types:[225]

- Separation

- Concentration

- Destruction

The type of PFAS remediation technology selected is often a reflection of the PFAS contamination levels and the PFAS signature (i.e. the combination of short- and long-chain PFAS substances present) in conjunction with the site-specific water chemistry and cross contaminants present in the liquid stream. More complex waters such as landfill leachates and WWTP waters require more robust treatment solutions which are less vulnerable to blockage.

Stripping and enrichment

[edit]Foam Fractionation utilizes the air/water interface of a rising air bubble to collect and harvest PFAS molecules. The hydrophobic tail of many long-chain criteria PFAS compounds adhere to this interface and rise to the water surface with the air bubble where they present as a foam for harvesting and further concentration. The foam fractionation technique is a derivation of traditional absorptive bubble separation techniques used by industries for decades to extract amphiphilic contaminants. The absence of a solid absorptive surface reduces consumables and waste byproducts and produces a liquid hyper-concentrate which can be fed into one of the various PFAS destruction technologies. Across various full-scale trials and field applications, this technique provides a simplistic and low operational cost alternative for complex PFAS-impacted waters.[228]

Destruction

[edit]In 2007, it was found that high-temperature incineration of sewage sludge reduced the levels of perfluorinated compounds significantly.[229]

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Environmental Engineering found that a heat- and pressure-based technique known as supercritical water oxidation destroyed 99% of the PFAS present in a water sample. During this process, oxidizing substances are added to PFAS-contaminated water and then the liquid is heated above its critical temperature of 374 degrees Celsius at a pressure of more than 220 bars. The water becomes supercritical, and, in this state, water-repellent substances such as PFASs dissolve much more readily.[226]

Theoretical and early-stage solutions

[edit]A possible solution for PFAS-contaminated wastewater treatment has been developed by the Michigan State University-Fraunhofer team. Boron-doped diamond electrodes are used for the electrochemical oxidation system where it is capable of breaking PFAS molecular bonds which essentially eliminates the contaminates, leaving fresh water.[230]

Acidimicrobium sp. strain A6 has been shown to be a PFAS and PFOS remediator.[231] PFAS with unsaturated bonds are easier to break down: the commercial dechlorination culture KB1 (contains Dehalococcoides) is capable of breaking down such substances, but not saturated PFAS. When alternative, easier-to-digest substrates are present, microbes may prefer them over PFAS.[232]

Chemical treatment

[edit]A study published in Science in August 2022 indicated that perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) can be mineralized via heating in a polar aprotic solvent such as dimethyl sulfoxide. Heating PFCAs in an 8 to 1 mixture of dimethyl sulfoxide and water at 80–120 °C (176–248 °F) in the presence of sodium hydroxide caused the removal of the carboxylic acid group at the end of the carbon chain, creating a perfluoroanion that mineralizes into sodium fluoride and other salts such as sodium trifluoroacetate, formate, carbonate, oxalate, and glycolate. The process does not work on perfluorosulfonic acids such as PFOS.[233] A 2022 study published in Chemical Science shows breakdown of C-F bonds and their mineralization as YF3 or YF6 clusters.[234] Another study in the Journal of the American Chemical Society described the PFASs breakdown using metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).[235]

Analytical methods

[edit]Analytical methods for PFAS analysis fall into one of two general categories; targeted analysis or non-targeted analysis. Targeted analyses use reference standards to determine concentrations of specific PFAS, but this requires a high-purity standard for each compound of interest. Due to the large number of possible targets, unusual PFAS may go unreported by these methods. Non-targeted analyses measure other factors, such as total organic fluorine, which can be used to estimate the total concentration of PFAS in a sample, but cannot provide concentrations of individual compounds. The two types of analyses are often combined; by subtracting the mass of target analytes from the non-targeted analysis results, one can get an estimate for what fraction of PFAS has been "missed" by the targeted analysis.

Targeted analysis generally use liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) instruments. Currently, EPA Method 537.1 is approved for use in drinking water and includes 18 PFAS.[236] EPA Method 1633 is undergoing review for use in wastewater, surface water, groundwater, soil, biosolids, sediment, landfill leachate, and fish tissue for 40 PFAS, but is currently being used by many laboratories in the United States.[237] Regulatory limits for PFOA and PFOS set by the US EPA (4 parts-per-trillion) are limited by the capability of methods to detect low level concentrations.[238]

Non-targeted analyses include total organic fluorine (TOF, including variations, e.g., adsorbable organic fluorine, AOF; extractable organic fluorine, EOF), total oxidizable precursor assay, and other methods in development.[239][240]

Sample chemicals

[edit]Some common per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances include:[241][242]

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (aka PTFE or Teflon)

- Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs)

- Perfluorosulfonic acids (PFSAs)

- Fluorotelomers (FTOHs)

| Name | Abbreviation | Structural formula | Molecular weight (g/mol) | CAS No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluorobutane sulfonamide | H-FBSA | C4F9SO2NH2 | 299.12 | 30334-69-1 |

| Perfluoropentanesulfonamide | PFPSA | C5F11SO2NH2 | 349.12 | 82765-76-2 |

| Perfluorohexanesulfonamide | PFHxSA | C6F13SO2NH2 | 399.13 | 41997-13-1 |

| Perfluoroheptanesulfonamide | PFHpSA | C7F15SO2NH2 | 449.14 | 82765-77-3 |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonamide | PFOSA | C8F17SO2NH2 | 499.14 | 754-91-6 |

| Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride | PFBSF | C4F9SO2F | 302.09 | 375-72-4 |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonyl fluoride | PFOSF | C8F17SO2F | 502.12 | 307-35-7 |

In popular culture

[edit]Films

[edit]- The Devil We Know (2018)

- Dark Waters (2019)

See also

[edit]- Timeline of events related to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

- Entegris, formerly Fluoroware, of Chaska, MN, manufacturer of teflon components for health and semiconductor Fabs

- FSI International, now TEL FSI

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)

- Fluoropolymer, subclass of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

- Euthenics, as the general category for policy interventions aiming to mitigate associated effects on human populations

References

[edit]- ^ "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)". 30 March 2016.

- ^ a b Reconciling Terminology of the Universe of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Recommendations and Practical Guidance. OECD Series on Risk Management of Chemicals. OECD. 2021. p. 23. doi:10.1787/e458e796-en. ISBN 978-92-64-51128-6.

- ^ Schymanski, Emma L.; Zhang, Jian; Thiessen, Paul A.; Chirsir, Parviel; Kondic, Todor; Bolton, Evan E. (23 October 2023). "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in PubChem: 7 Million and Growing". Environmental Science & Technology. 57 (44). American Chemical Society: 16918–16928. Bibcode:2023EnST...5716918S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.3c04855. PMC 10634333. PMID 37871188.

- ^ Bagenstose, Kyle (7 March 2022). "What are PFAS? A guide to understanding chemicals behind nonstick pans, cancer fears". USA TODAY.

- ^ a b c "PFAS Explained". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 30 March 2016.

- ^ a b KLUGER, JEFFREY (19 May 2023). "All The Stuff in Your Home That Might Contain PFAS 'Forever Chemicals'". Time.

- ^ "What are PFAS?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 January 2024.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (15 June 2021). "Toxic 'forever chemicals' widespread in top makeup brands, study finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021.

- ^ Whitehead HD, Venier M, Wu Y, Eastman E, Urbanik S, Diamond ML, et al. (15 June 2021). "Fluorinated Compounds in North American Cosmetics". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 8 (7): 538–544. Bibcode:2021EnSTL...8..538W. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00240. hdl:20.500.11850/495857. S2CID 236284279.

- ^ "Opinion: These toxic chemicals are everywhere — even in your body. And they won't ever go away". The Washington Post. 2 January 2018. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) Factsheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, Conder JM, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, et al. (October 2011). "Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins". Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. 7 (4): 513–541. Bibcode:2011IEAM....7..513B. doi:10.1002/ieam.258. PMC 3214619. PMID 21793199.

- ^ Turkewitz J (22 February 2019). "Toxic 'Forever Chemicals' in Drinking Water Leave Military Families Reeling". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019.

- ^ Kounang, Nadia (3 June 2019). "FDA confirms PFAS chemicals are in the US food supply". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019.

- ^ "Companies deny responsibility for toxic 'forever chemicals' contamination". The Guardian. 11 September 2019. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d Munoz G, Budzinski H, Babut M, Drouineau H, Lauzent M, Menach KL, et al. (August 2017). "Evidence for the Trophic Transfer of Perfluoroalkylated Substances in a Temperate Macrotidal Estuary" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (15): 8450–8459. Bibcode:2017EnST...51.8450M. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02399. PMID 28679050.

- ^ Elton, Charlotte (24 February 2023). "'Frightening' scale of Europe's forever chemical pollution revealed". Euronews.

- ^ "Toxic 'Forever Chemicals' Widespread in Top Makeup Brands, Study Finds; Researchers Find Signs of PFAS in over Half of 231 Samples of Products Including Lipstick, Mascara and Foundation". The Guardian. UK. 15 June 2021. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS". 7 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Emerging chemical risks in Europe — 'PFAS'". European Environment Agency. 12 December 2019.

- ^ "New Report Calls for Expanded PFAS Testing for People With History of Elevated Exposure, Offers Advice for Clinical Treatment" (Press release). National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 28 July 2022.

- ^ a b Zahm S, Bonde JP, Chiu WA, Hoppin J, Kanno J, Abdallah M, et al. (November 2023). "Carcinogenicity of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid". The Lancet. 25 (1): 16–17. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00622-8. PMID 38043561. S2CID 265571186.

- ^ a b c Perkins, Tom (13 January 2023). "Bills to regulate toxic 'forever chemicals' died in Congress – with Republican help". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ DeWitt, Jamie C.; Glüge, Juliane; Cousins, Ian T.; Goldenman, Gretta; Herzke, Dorte; Lohmann, Rainer; Miller, Mark; Ng, Carla A.; Patton, Sharyle; Trier, Xenia; Vierke, Lena; Wang, Zhanyun; Adu-Kumi, Sam; Balan, Simona; Buser, Andreas M.; Fletcher, Tony; Haug, Line Småstuen; Huang, Jun; Kaserzon, Sarit; Leonel, Juliana; Sheriff, Ishmail; Shi, Ya-Li; Valsecchi, Sara; Scheringer, Martin (22 April 2024). "Zürich II Statement on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): Scientific and Regulatory Needs". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 11 (8): 786–797. Bibcode:2024EnSTL..11..786D. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.4c00147. hdl:20.500.11850/679165. PMC 11325642. PMID 39156923.

- ^ "PFAS POLLUTION ACROSS THE MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA" (PDF). International Pollutants Elimination Network. April 2019.

- ^ a b Halpern, Michael (16 May 2018). "Bipartisan Outrage as EPA, White House Try to Cover Up Chemical Health Assessment". Cambridge, Massachusetts: Union of Concerned Scientists. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020.

- ^ a b SNIDER, ANNIE (14 May 2018). "White House, EPA headed off chemical pollution study". Politico. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018.

- ^ "The top 12 PFAS producers in the world and the staggering societal costs of PFAS pollution". ChemSec. 25 May 2023.

- ^ a b Perkins, Tom (12 May 2023). "Societal cost of 'Forever Chemicals' About $17.5tn Across Global Economy—Report". The Guardian.

- ^ Ram, Archana (22 March 2023). "Say Goodbye to "Forever Chemicals"". Patagonia, Inc.

- ^ Snider, Mike (22 February 2023). "REI announces plan to remove 'forever chemicals' from its products by 2026". USA TODAY.

- ^ "Phasing out PFAS". H&M. 27 February 2019.

- ^ Tullo, Alexander H. (29 December 2022). "3M says it will end PFAS production by 2025". Chemical & Engineering News. Vol. 101, no. 1. p. 4. doi:10.1021/cen-10101-leadcon.

- ^ "3M to Exit PFAS Manufacturing by the End of 2025" (Press release). 3M. 20 December 2022.

- ^ Condon, Christine (15 February 2024). "Amid pollution investigation, maker of Gore-Tex cuts PFAS from outdoor clothing". The Spokesman-Review. The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ a b "3M pays $10.3bn to settle water pollution suit over 'forever chemicals'". The Guardian. 22 June 2023. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ a b c Gaber N, Bero L, Woodruff TJ (1 June 2023). "The Devil they Knew: Chemical Documents Analysis of Industry Influence on PFAS Science". Annals of Global Health. 89 (1): 37. doi:10.5334/aogh.4013. PMC 10237242. PMID 37273487.

- ^ "Nordic Council of Ministers (2019). The cost of inaction. A socioeconomic analysis of environmental and health impacts linked to exposure" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2019.

- ^ Obsekov V, Kahn LG, Trasande L (26 July 2022). "Leveraging Systematic Reviews to Explore Disease Burden and Costs of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Exposures in the United States". Exposure and Health. 15 (2): 373–394. doi:10.1007/s12403-022-00496-y. ISSN 2451-9766. PMC 10198842. PMID 37213870. S2CID 251072281.

- ^ "Daily Exposure to 'Forever Chemicals' Costs United States Billions in Health Costs" (Press release). NYU Langone Health. 26 July 2022.

- ^ "PFAS structures in DSSTox". CompTox Chemicals Dashboard. United States Environmental Protection Agency. "List consists of all DTXSID records with a structure assigned, and using a set of substructural filters based on community input."

- ^ Gaines, Linda G. T.; Sinclair, Gabriel; Williams, Antony J. (2023). "A proposed approach to defining per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) based on molecular structure and formula". Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. 19 (5): 1333–1347. Bibcode:2023IEAM...19.1333G. doi:10.1002/ieam.4735. ISSN 1551-3777. PMC 10827356. PMID 36628931.

- ^ Wang Z, Buser AM, Cousins IT, Demattio S, Drost W, Johansson O, et al. (December 2021). "A New OECD Definition for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances". Environmental Science & Technology. 55 (23): 15575–15578. Bibcode:2021EnST...5515575W. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c06896. PMID 34751569. S2CID 243861839.

- ^ "Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List 5-Final". Federal Register. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Hammel, Emily; Webster, Thomas F.; Gurney, Rich; Heiger-Bernays, Wendy (April 2022). "Implications of PFAS definitions using fluorinated pharmaceuticals". iScience. 25 (4): 104020. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j4020H. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104020. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 8933701. PMID 35313699.

- ^ Kovalchuk, N M; Trybala, A; Starov, V; Matar, O; Ivanova, N (August 2014). "Fluoro- vs hydrocarbon surfactants: why do they differ in wetting performance?". Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 210: 65–71. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2014.04.003. hdl:10044/1/26321. PMID 24814169.

- ^ Schaefer, Charles E.; Culina, Veronika; Nguyen, Dung; Field, Jennifer (5 November 2019). "Uptake of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances at the Air–Water Interface". Environmental Science & Technology. 53 (21): 12442–12448. Bibcode:2019EnST...5312442S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b04008. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 31577432.

- ^ Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL (November 2007). "Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999-2000". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (11): 1596–1602. doi:10.1289/ehp.10598. PMC 2072821. PMID 18007991.

- ^ Wang Z, Cousins IT, Berger U, Hungerbühler K, Scheringer M (2016). "Comparative assessment of the environmental hazards of and exposure to perfluoroalkyl phosphonic and phosphinic acids (PFPAs and PFPiAs): Current knowledge, gaps, challenges and research needs". Environment International. 89–90: 235–247. Bibcode:2016EnInt..89..235W. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.01.023. PMID 26922149.

- ^ a b Renner R (January 2006). "The long and the short of perfluorinated replacements". Environmental Science & Technology. 40 (1): 12–13. Bibcode:2006EnST...40...12R. doi:10.1021/es062612a. PMID 16433328.

- ^ a b Hogue, Cheryl (27 May 2019). "A guide to the PFAS found in our environment". Chemical & Engineering News. 97 (21): 12. doi:10.1021/cen-09721-polcon2. ISSN 2474-7408. S2CID 199655540.

- ^ "Preliminary Lists of PFOS, PFAS, PFOA and Related Compounds and Chemicals that May Degrade to PFCA". OECD Papers. 6 (11): 1–194. 25 October 2006. doi:10.1787/oecd_papers-v6-art38-en. ISSN 1609-1914.

- ^ a b c d Ubel FA, Sorenson SD, Roach DE (August 1980). "Health status of plant workers exposed to fluorochemicals—a preliminary report". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. 41 (8): 584–589. doi:10.1080/15298668091425310. PMID 7405826.

- ^ a b c Olsen GW, Burris JM, Burlew MM, Mandel JH (March 2003). "Epidemiologic assessment of worker serum perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) concentrations and medical surveillance examinations". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 45 (3): 260–270. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000052958.59271.10. PMID 12661183. S2CID 11648767.

- ^ "Some Chemicals Used as Solvents and in Polymer Manufacture". IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 110. 2016. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020.

- ^ Fenton SE, Reiner JL, Nakayama SF, Delinsky AD, Stanko JP, Hines EP, et al. (June 2009). "Analysis of PFOA in dosed CD-1 mice. Part 2. Disposition of PFOA in tissues and fluids from pregnant and lactating mice and their pups". Reproductive Toxicology. 27 (3–4): 365–372. Bibcode:2009RepTx..27..365F. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.02.012. PMC 3446208. PMID 19429407.

- ^ Cousins IT, Johansson JH, Salter ME, Sha B, Scheringer M (August 2022). "Outside the Safe Operating Space of a New Planetary Boundary for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)". Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (16). American Chemical Society: 11172–11179. Bibcode:2022EnST...5611172C. doi:10.1021/acs.est.2c02765. PMC 9387091. PMID 35916421.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (18 December 2021). "PFAS 'forever chemicals' constantly cycle through ground, air and water, study finds". The Guardian.

- ^ Sha B, Johansson JH, Tunved P, Bohlin-Nizzetto P, Cousins IT, Salter ME (January 2022). "Sea Spray Aerosol (SSA) as a Source of Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) to the Atmosphere: Field Evidence from Long-Term Air Monitoring". Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (1). American Chemical Society: 228–238. Bibcode:2022EnST...56..228S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04277. PMC 8733926. PMID 34907779.

- ^ Sha, Bo; Johansson, Jana H.; Salter, Matthew E.; Blichner, Sara M.; Cousins, Ian T. (2024). "Constraining global transport of perfluoroalkyl acids on sea spray aerosol using field measurements". Science Advances. 10 (14): eadl1026. Bibcode:2024SciA...10L1026S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adl1026. PMC 10997204. PMID 38579007.

- ^ Erdenesanaa, Delger (8 April 2024). "PFAS 'Forever Chemicals' Are Pervasive in Water Worldwide". The New York Times.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (2 August 2022). "Pollution: 'Forever chemicals' in rainwater exceed safe levels". BBC News.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (22 March 2022). "'I don't know how we'll survive': the farmers facing ruin in America's 'forever chemicals' crisis". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b Wang, Yuting; Gui, Jiang; Howe, Caitlin G.; Emond, Jennifer A.; Criswell, Rachel L.; Gallagher, Lisa G.; Huset, Carin A.; Peterson, Lisa A.; Botelho, Julianne Cook; Calafat, Antonia M.; Christensen, Brock; Karagas, Margaret R.; Romano, Megan E. (July 2024). "Association of diet with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in plasma and human milk in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study". Science of the Total Environment. 933: 173157. Bibcode:2024ScTEn.93373157W. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173157. ISSN 0048-9697. PMC 11247473. PMID 38740209.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (4 July 2024). "Coffee, eggs and white rice linked to higher levels of PFAS in human body". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b "C8 Science Panel". c8sciencepanel.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019.

- ^ Steenland K, Jin C, MacNeil J, Lally C, Ducatman A, Vieira V, Fletcher T (July 2009). "Predictors of PFOA levels in a community surrounding a chemical plant". Environmental Health Perspectives. 117 (7): 1083–1088. doi:10.1289/ehp.0800294. PMC 2717134. PMID 19654917.

- ^ "Probable Link Evaluation for heart disease (including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, coronary artery disease)" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. 29 October 2012.

- ^ "Probable Link Evaluation of Autoimmune Disease" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Probable Link Evaluation of Thyroid disease" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Probable Link Evaluation of Cancer" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. 15 April 2012.

- ^ "Probable Link Evaluation of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension and Preeclampsia" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. 5 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Toxicological profile for Perfluoroalkyls". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2018. doi:10.15620/cdc:59198. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021.

- ^ Erinc A, Davis MB, Padmanabhan V, Langen E, Goodrich JM (June 2021). "Considering environmental exposures to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as risk factors for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy". Environ Res (Review). 197: 111113. Bibcode:2021ER....19711113E. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111113. PMC 8187287. PMID 33823190.

- ^ "PFAS and Breastfeeding". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 17 January 2024.

- ^ Swan, Shanna H.; Colino, Stacey (23 February 2021). Count down: how our modern world is threatening sperm counts, altering male and female reproductive development, and imperiling the future of the human race. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-1-9821-1366-7.

- ^ Huet, Natalie (24 March 2023). "Can't get pregnant? PFAS chemicals in household products may be slashing women's fertility by 40%". Euronews.

- ^ "Exposure to Chemicals Found in Everyday Products Is Linked to Significantly Reduced Fertility". Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (Press release). 17 March 2023.

- ^ Costello E, Rock S, Stratakis N, Eckel SP, Walker DI, Valvi D, et al. (April 2022). "Exposure to per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Markers of Liver Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 130 (4): 46001. doi:10.1289/EHP10092. PMC 9044977. PMID 35475652.

- ^ Steenland K, Winquist A (March 2021). "PFAS and cancer, a scoping review of the epidemiologic evidence". Environmental Research (Review). 194: 110690. Bibcode:2021ER....19410690S. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.110690. PMC 7946751. PMID 33385391.

- ^ DeWitt JC, Shnyra A, Badr MZ, Loveless SE, Hoban D, Frame SR, et al. (8 January 2009). "Immunotoxicity of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate and the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 39 (1): 76–94. doi:10.1080/10408440802209804. PMID 18802816. S2CID 96896603.

- ^ DeWitt JC, Peden-Adams MM, Keller JM, Germolec DR (22 November 2011). "Immunotoxicity of perfluorinated compounds: recent developments". Toxicologic Pathology. 40 (2): 300–311. doi:10.1177/0192623311428473. PMID 22109712. S2CID 35549835.

- ^ Steenland K, Zhao L, Winquist A, Parks C (August 2013). "Ulcerative colitis and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in a highly exposed population of community residents and workers in the mid-Ohio valley". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (8): 900–905. doi:10.1289/ehp.1206449. PMC 3734500. PMID 23735465.

- ^ a b Lee JE, Choi K (March 2017). "Perfluoroalkyl substances exposure and thyroid hormones in humans: epidemiological observations and implications". Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 22 (1): 6–14. doi:10.6065/apem.2017.22.1.6. PMC 5401824. PMID 28443254.

- ^ Song M, Kim YJ, Park YK, Ryu JC (August 2012). "Changes in thyroid peroxidase activity in response to various chemicals". Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 14 (8): 2121–2126. doi:10.1039/c2em30106g. PMID 22699773.

- ^ Munoz G, Budinski H, Babut M, Drouineau H, Lauzent M, Menach KL (July 2017). "Evidence for the trophic transfer of perfluoroalkylated substances in a temperate macrotidal estuary" (PDF). Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (15): 8450–8459. Bibcode:2017EnST...51.8450M. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02399. PMID 28679050.

- ^ Ballutaud M, Drouineau H, Carassou L, Munoz G, Chevillot X, Labadie P, et al. (March 2019). "EStimating Contaminants tRansfers Over Complex food webs (ESCROC): An innovative Bayesian method for estimating POP's biomagnification in aquatic food webs". The Science of the Total Environment. 658: 638–649. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.658..638B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.058. PMID 30580218. S2CID 58660816.

- ^ Martin JW, Mabury SA, Solomon KR, Muir DC (January 2003). "Bioconcentration and tissue distribution of perfluorinated acids in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 22 (1): 196–204. doi:10.1002/etc.5620220126. PMID 12503765. S2CID 12659454.

- ^ LaMotte, Sandee (17 January 2023). "Locally caught fish are full of dangerous chemicals called PFAS, study finds". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023.

- ^ Barbo N, Stoiber T, Naidenko OV, Andrews DQ (March 2023). "Locally caught freshwater fish across the United States are likely a significant source of exposure to PFOS and other perfluorinated compounds". Environmental Research. 220: 115165. Bibcode:2023ER....22015165B. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2022.115165. PMID 36584847. S2CID 255248441.

- ^ Choi S, Kim JJ, Kim MH, Joo YS, Chung MS, Kho Y, Lee KW (June 2020). "Origin and organ-specific bioaccumulation pattern of perfluorinated alkyl substances in crabs". Environmental Pollution. 261: 114185. Bibcode:2020EPoll.26114185C. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114185. PMID 32114125. S2CID 211727091.

- ^ a b Fair PA, Wolf B, White ND, Arnott SA, Kannan K, Karthikraj R, Vena JE (April 2019). "Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in edible fish species from Charleston Harbor and tributaries, South Carolina, United States: Exposure and risk assessment". Environmental Research. 171: 266–277. Bibcode:2019ER....171..266F. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2019.01.021. PMC 6943835. PMID 30703622.

- ^ Teunen L, Bervoets L, Belpaire C, De Jonge M, Groffen T (29 March 2021). "PFAS accumulation in indigenous and translocated aquatic organisms from Belgium, with translation to human and ecological health risk". Environmental Sciences Europe. 33 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/s12302-021-00477-z. hdl:10067/1769070151162165141. ISSN 2190-4715. S2CID 232414650.

- ^ "Proceedings of the 2023 National Forum on Contaminants in Fish" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. June 2023.

- ^ Wang Z, Cousins IT, Scheringer M, Hungerbuehler K (February 2015). "Hazard assessment of fluorinated alternatives to long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) and their precursors: status quo, ongoing challenges and possible solutions". Environment International. 75: 172–179. Bibcode:2015EnInt..75..172W. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.013. PMID 25461427.

- ^ Birnbaum LS, Grandjean P (May 2015). "Alternatives to PFASs: perspectives on the science". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (5): A104–105. doi:10.1289/ehp.1509944. PMC 4421778. PMID 25932670.

- ^ Perry MJ, Nguyen GN, Porter ND (2016). "The Current Epidemiologic Evidence on Exposures to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) and Male Reproductive Health". Current Epidemiology Reports. 3 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1007/s40471-016-0071-y. ISSN 2196-2995. S2CID 88276945.

- ^ Scheringer M, Trier X, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, Fletcher T, Wang Z, Webster TF (November 2014). "Helsingør statement on poly- and perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs)". Chemosphere. 114: 337–339. Bibcode:2014Chmsp.114..337S. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.044. hdl:20.500.11850/84912. PMID 24938172. S2CID 249995685.

- ^ Léandri-Breton, Don-Jean, et al., Winter Tracking Data Suggest that Migratory Seabirds Transport Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances to Their Arctic Nesting Site, ACS Publications, July 11, 2024