Fiore dei Liberi

Fiore Furlano de'i Liberi | |

|---|---|

This master with a forked beard appears sporadically throughout both the Getty and Pisani Dossi mss., and may be a representation of Fiore himself. | |

| Born | c. 1350 Cividale del Friuli, Friuli (now Italy) |

| Died | after 1409 |

| Occupation | Diplomat, Fencing master, Mercenary |

| Language | Friulian, Italian, Renaissance Latin |

| Nationality | Friulian |

| Employers | |

| Notable works | The Flower of Battle List of manuscripts

|

| Relatives | Benedetto de'i Liberi (father) |

Fiore Furlano de Cividale d'Austria, delli Liberi da Premariacco (Fiore dei Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d'Austria; born ca. 1350;[1] died after 1409[2]) was a late 14th century knight, diplomat, and itinerant fencing master.

He is the earliest Italian master from whom an extant[update] martial arts manual has survived. His Flower of Battle (Fior di Battaglia, Flos Duellatorum) is among the oldest surviving fencing manuals.[3]

Life

[edit]Fiore dei Liberi was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy, the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco.[4][5][6] The term Liberi, while potentially merely a surname, probably indicates that his family had imperial immediacy, either as part of the Edelfrei (nobili liberi, "free nobles"), the Germanic unindentured knightly class which formed the lower tier of nobility in the Middle Ages, or possibly of the rising class of Imperial Free Knights.[7][8][9] It has been suggested by various historians that Fiore and Benedetto were descended from Cristallo dei Liberi of Premariacco, who was granted immediacy in 1110 by Emperor Henry V,[10][11][12] but this has yet to be confirmed.[13]

Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with "countless" masters from both the Italian and German parts of the Holy Roman Empire.[14]

He also writes of meeting many "false" or unworthy masters who lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student,[6] and mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight duels for his honor against certain of these masters whom he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp longswords, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he stated that he won each without injury.[4][5]

He further offers an extensive list of the famous condottieri that he trained, including Piero Paolo del Verde (Peter von Grünen),[15] Niccolo Unricilino (Nikolo von Urslingen),[16] Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli (Galeazzo Gonzaga da Mantova),[17] Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia,[18] Giovannino da Baggio di Milano,[19] and Azzone di Castelbarco,[20] and also highlights some of their martial exploits.[4][5]

Based on Fiore's autobiographical account, he can tentatively be placed in Perosa (Perugia) in 1381 when Piero del Verde likely fought a duel with Pietro della Corona (Peter Kornwald).[21] That same year, the Aquileian War of Succession erupted as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly appointed Patriarch, Philippe II d'Alençon. Fiore seems to have sided with the secular nobility against the cardinal as in 1383 there is record of him being tasked by the grand council with inspection and maintenance on the artillery pieces defending Udine (including large crossbows and catapults).[8][22][23] There are also records of him working variously as a magistrate, peace officer, and agent of the grand council during the course of 1384, but after that the historical record is silent. The war continued until a new Patriarch was appointed in 1389 and a peace settlement was reached, but it's unclear if Fiore remained involved for the duration. Given that he appears in council records five times in 1384, it would be quite odd for him to be completely unmentioned over the subsequent five years,[8] and since his absence after May 1384 coincides with a proclamation in July of that year demanding that Udine cease hostilities or face harsh repercussions, it seems more likely that he moved on.[24]

After the war, Fiore seems to have traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. In 1395, Fiore can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French Marshal Jean II Le Maingre (who used the war name "Boucicaut"). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. Both Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco I Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, were in attendance. The duel was to begin with spears on horseback, but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking his opponent before he could mount his own horse. Cattaneo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman's helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut reached for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel.[17][23][25]

Fiore surfaces again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was fought on 24 June and attended by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, as well as the duchess and other nobles. The duel was to consist of three bouts of mounted lance followed by three bouts each of dismounted poleaxe, estoc, and dagger. They ultimately rode two additional passes and on the fifth, Baggio impaled Sirano's horse through the chest, slaying the horse but losing his lance in the process. They fought the other nine bouts as scheduled, and due to the strength of their armor (and the fact that all of the weapons were blunted), both combatants reportedly emerged from these exchanges unharmed.[19][26]

Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, between his final named student Azzone di Castelbarco and Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399.[27] After Castelbarco's duels, Fiore's activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career.[23] Some time in the first years of the 15th century, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as Fior di Battaglia, Florius de Arte Luctandi, and Flos Duellatorum). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort;[6] as evidence suggests that two longer versions were composed some time before this,[28] we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade.

Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. Francesco Novati and D. Luigi Zanutto both assume that some time before 1409 he accepted an appointment as court fencing master to Niccolò III d'Este, Marquis of Ferrara, Modena, and Parma; presumably he would have made this change when Milan fell into disarray in 1402, though Zanutto went so far as to speculate that he trained Niccolò for his 1399 passage at arms.[29] However, while two surviving copies of "the Flower of Battle" are dedicated to the marquis, it seems more likely that the manuscripts were written as a diplomatic gift to Ferrara from Milan when they made peace in 1404.[23][26]

C. A. Blengini di Torricella stated that late in life he made his way to Paris, France, where he could be placed teaching fencing in 1418 and creating a copy of a fencing manual located there in 1420. Though he attributes these facts to Novati, no publication verifying them has yet been located.[30] The time and place of Fiore's death remain unknown.

Despite the depth and complexity of his writings, Fiore dei Liberi does not seem to have been a very influential master in the development of Italian fencing. That field was instead dominated by the tradition of his near-contemporary the Bolognese master Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi. Even so, there are a number of later treatises which bear strong resemblance to his work, including the writings of Philippo di Vadi and Ludwig VI von Eyb of Hartenstein. This may be due to the direct influence of Fiore or his writings, or it may instead indicate that the older tradition of Johane and Nicholai survived and spread outside of his direct line.

The Flower of Battle

[edit]Four illuminated manuscript copies of this treatise survive, and there are records of at least two others whose current locations are unknown. The Ms. Ludwig XV 13 and the Pisani Dossi Ms. are both dedicated to Niccolò III d'Este and state that they were written at his request and according to his design. The Ms. M.383, on the other hand, lacks a dedication and claims to have been laid out according to his own intelligence while the Mss. Latin 11269 lost any dedication it might have had along with its prologue. Each of the extant copies of the Flower of Battle follows a distinct order, though both of these pairs contain strong similarities to each other in order of presentation.

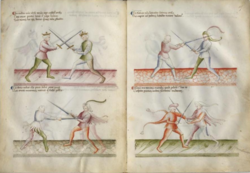

The major sections of the work include: abrazare, unarmed plays (usually translated as wrestling but more literally grappling); daga, including both unarmed defenses against the dagger and plays of dagger against dagger; spada a un mano, the use of the sword in one hand (also called "the sword without the buckler"); spada a dui mani, the use of the sword in two hands; spada en arme, the use of the sword in armor (primarily techniques from the halfsword); azza, plays of the poleaxe in armor; lancia, spear and staff plays; and mounted combat (including the spear, the sword, and grappling). Brief bridging sections serve to connect each of these, covering such topics as bastoncello, or plays of a small stick or baton against unarmed and dagger-wielding opponents; plays of longsword vs. dagger; plays of staff and dagger and of two clubs and a dagger; and the use of the chiavarina against a man on horseback.

The format of instruction is largely consistent across all copies of the treatise. Each section begins with a group of Masters (or Teachers), figures in golden crowns who each demonstrate a particular guard for use with their weapon. These are followed by a master called "Remedio" (remedy) who demonstrates a defensive technique against some basic attack (usually how to use one of the listed guards to defend), and then by his various Scholars (or Students), figures wearing golden garters on their legs who demonstrate iterations and variations of this remedy. After the scholars there is typically a master called "Contrario" (counter), wearing both crown and garter, who demonstrates how to counter the master's remedy (and those of his scholars), who is likewise sometimes followed by his own scholars in garters. In rare cases, a fourth type of master appears called "Contra-Contrario" (counter-counter), who likewise wears the crown and garter and demonstrates how to defeat the master's counter. Some sections feature multiple master remedies or master counters, while some have only one. There are also many cases in which an image in one manuscript will only feature a scholar's garter where the corresponding image in another also includes a master's crown. Depending on the instance, this may either be intentional or merely an error in the art.

Fior di Battaglia (Ms. M.383)

[edit]B1.370.A Ms. M.0383 | |

|---|---|

| The Morgan Library & Museum | |

Folia 13v–14r | |

| Date | before 1409 |

| Place of origin | Milan, Italy |

| Language(s) | Medieval Italian |

| Scribe(s) | Unknown |

| Author(s) | Fiore dei Liberi |

| Illuminated by | Unknown |

| Material | Vellum, in a modern binding |

| Size | 20 folia, 277×195 mm |

| Format | Double-sided; four illustrations per side, with text above |

| Condition | Incomplete |

| Script | Bastarda |

| Other | Catalog listing |

The Ms. M.383, titled Fior di Battaglia, is in the holdings of the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City, NY. Novati described it as a small, thin, vellum folio, pen and ink with gold highlights, and illustrations of sword and lance combat on foot and horseback.[23] Unlike the other surviving manuscripts, the swords and other weapons were enameled in silver, though it has since tarnished to a glossy black. This is the briefest copy of Fiore's work currently known, with only 19 folios; it has a prologue in Italian and four illustrated figures per page in the main body. The figures are accompanied by text that is often identical to that of the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 (excepting differences in spelling), but at times includes additional explanation. The Ms. M.383 is almost certainly longer when it was first written; its text makes reference to sections on poleaxe, dagger, and grappling which are not present in the book's current state. It also refers to a certain play of the sword in one hand which is likewise missing from that section. This manuscript is typically referred to as the 'Pierpont Morgan version' or simply the 'Morgan'.

The known provenance of the Ms. M.383 is:[31]

- Written between 1400 and 1409. The Pisani Dossi Ms. dates to 1409 and states that the master had fifty years of experience in the martial arts; the Ms. M.383 and the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 both state that he had been training for "forty years and more", which makes them slightly older.

- before 1780 – it occupied ff 241–259 of a larger collective binding titled, Arte di armeggiare a piedi ed acavallo (codex Soranzo MCCLXI) in the Biblioteca Soranzo in Venice (Library of Jacopo Soranzo, Venetian senator, 18th century). The other contents of this codex are unknown.

- 1780–1836 – the collection of the Venetian former Jesuit Matteo Luigi Canonici (1727–c.1806) (sold London, Sotheby's, 15 June 1836, no. 40).

- 1836–1903 – owned by Rev. Walter Sneyd of Bagington Rectory, Coventry (sold London, Sotheby's, 19 Dec. 1903, no. 720).

- 1903–1909 – owned by Tammaro de Marinis (catalog 8, 1908, plate 9).

- 1909–1913 – owned by John Pierpont Morgan.

- 1913–1924 – owned by John Pierpont Morgan, Jr. (donated 1924).

- 1924–present – held by the Morgan Library & Museum.

The contents of the Ms. M.383 are as follows:

- Prologue (ff 1r–2r)

- Mounted combat (ff 2v–8r)

- Spear vs. cavalry (ff 8r–8v)

- Lanza plays (ff 9r–9v)

- Spada en arme stances (ff 10r–10v)

- Spada en arme plays (ff 10v–11v)

- Spada a dui mani stances (ff 12r–13r)

- Spada a dui mani wide plays (ff 13v–14v)

- Spada a dui mani close plays (ff 15r–16v)

- Sword vs. dagger play (f 17r)

- Spada a un mano plays (f 17v)

- Longsword against spear/spear and dagger against spear (f 18r)

- Sword vs. dagger plays (ff 18r–18v)

- Spada a un mano play (f 19r)

Fior di Battaglia (Ms. Ludwig XV 13)

[edit]Ms. Ludwig XV 13 | |

|---|---|

| The J. Paul Getty Museum | |

Folia 27v–28r | |

| Date | before 1409 |

| Place of origin | Venice, Italy |

| Language(s) | Medieval Italian |

| Scribe(s) | Unknown |

| Author(s) | Fiore dei Liberi |

| Illuminated by | At least two artists |

| Dedicated to | Niccolò III d'Este |

| Material | Parchment, in a pasteboard leather binding |

| Size | 49 folia, 279×206 mm |

| Format | Double-sided; four illustrations per side, with text above |

| Script | Bastarda |

| Other | Catalog listing |

The Ms. Ludwig XV 13, also titled Fior di Battaglia, is currently in the holdings of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, CA. Its prologue, format, illustrations, and text are all very similar to the Ms. M.383, though it's largely free of silver enamel. The text takes the form of descriptive paragraphs set in poor Italian verse,[32] which are nevertheless fairly clear and informative. Despite its shared characteristics with the Ms. M.383, there are important differences, not the least of which is the vastly different order of the information. This is the longest and most comprehensive of the four manuscripts of Fior di Battaglia. This manuscript is typically referred to as the 'Getty version'.

The known provenance of the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 is:[23]

- Written between 1400 and 1409. The Pisani Dossi Ms. dates to 1409 and states that the master had fifty years of experience in the martial arts; the Ms. M.383 and the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 both state that he had been training for "forty years and more", which makes them slightly older.

- before 1474 – owned by Nicolò Marcello of Venice.

- ca. 1699 – gifted to Apostolo Zeno (1668–1750), who created a copy of the preface.

- before 1825 – owned by Luigi Celotti (sold London, Sotheby's, 1825)).

- 1825–1966 – the Ms. 4202 in the collection of Thomas Phillipps (sold London, Sotheby's, 1966).

- 1966–1983 – the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 in the collection of Peter and Irene Ludwig.

- 1983–present – the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 in the J. Paul Getty Museum.

The contents of the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 are as follows:

- Prologue (ff 1v–2v)

- (ff 3r–5v – blank pages)

- Abrazare stances (f 6r)

- Abrazare plays (ff 6v–8r)

- Bastoncello plays (f 8v)

- Daga stances (f 9r)

- Daga intro (ff 9v–10r)

- Daga plays (ff 10v–18v)

- Sword vs. dagger plays (ff 19r–20r)

- Spada a un mano plays (ff 20r–21v)

- Spada a dui mani intro (ff 22r–22v)

- Four strikes of the sword (f 23r)

- Spada a dui mani stances (ff 23v–24v)

- Spada a dui mani wide plays (ff 25r–27v)

- Spada a dui mani close plays (ff 27v–30v)

- Longsword against spear/spear and dagger against spear (ff 31r–31v)

- The seven swords (f 32r)

- Spada en arme stances (ff 32v–33r)

- Spada en arme plays (ff 33r–35r)

- Azza stances (ff 35v–36r)

- Azza plays (36v–37v)

- Daga plays (ff 38r–38v)

- Lanza plays (ff 39r–40r)

- (ff 40v – blank page)

- Mounted combat plays (ff 41r–45v)

- Spear vs. cavalry (f 46r)

- Mounted combat plays (f 46v)

- Closing (ff 46v–47r)

Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi Ms.)

[edit]Pisani Dossi Ms. | |

|---|---|

| Private collection | |

Folia 18v–19r | |

| Date | 10 February 1409 |

| Place of origin | Venice, Italy |

| Language(s) | Medieval Italian Renaissance Latin |

| Scribe(s) | Unknown |

| Author(s) | Fiore dei Liberi |

| Illuminated by | Altichiero da Zevio (?) |

| Dedicated to | Niccolò III d'Este |

| Material | Parchment, in a cardboard folder |

| Size | 36 folia |

| Format | Double-sided; four to six illustrations per side, with text above |

| Script | Bastarda |

The Pisani Dossi Ms., titled Flos Duellatorum, was believed to have been lost in World War II and only resurfaced in a private collection in Italy in 2005.[23] Novati described this manuscript as an unbound collection of leaves, covered with a cardboard folder with a marbled paper cover.[33] The Pisani Dossi Ms. is the only manuscript in the series that includes a date, claiming to be completed on 10 February 1409 after six months of effort. It consists of 36 folia and possesses two different prologues, one in Renaissance Latin and one in Italian. The body of the text consists of four to six illustrations per page, each with only a brief couplet or quatrain to explain it. This manuscript is typically referred to as either the 'Novati' or 'Pisani Dossi version'.

The Pisani Dossi Ms. was published in facsimile by Francesco Novati in 1902, including the only reproductions of a copy of the Flower of Battle that are clearly in the public domain. However, it is unclear how accurate this facsimile is as evidence suggests that Novati may have hired an artist to create a tracing of the original manuscript rather than reproducing it directly.[citation needed] This would have provided ample opportunity for errors to creep into the images, and might also account for the significant divergences from the artistic style of the Getty and the Morgan.

The known provenance of the Pisani Dossi Ms. is:[23]

- Completed by Fiore de'i Liberi on 10 February 1409. Though it was dedicated to Niccolò III d'Este, there is no evidence that it ever passed into his library.

- before 1663 – belonged to Schier de' Prevosti da Valbregaglia, passed into the library of the Sacchi da Bucinigo family (purchased before 1902, Carlo Alberto Pisani Dossi).

- before 1902–present – owned by the Pisani Dossi family.

The contents of the Pisani Dossi Ms. are as follows:

- Latin Prologue (f 1r)

- Italian Prologue (ff 1r–1v)

- (ff 2r–2v – blank pages)

- Abrazare stances (f 3r)

- Abrazare plays (ff 3v–4v)

- Bastoncello plays (f 4v)

- Daga intro (f 5r)

- Daga plays (ff 5r–11v)

- Four strikes of the sword (ff 11v–12r)

- Spada a un mano plays (ff 12r–13v)

- Lanza plays (ff 14v–15v)

- Longsword against spear/unarmed against spear (f 15r)

- The seven swords (f 16v)

- Spada a dui mani stances (ff 16r–18r)

- Spada a dui mani wide plays (ff 19v–20v)

- Spada a dui mani close plays (ff 21r–23v)

- Spada en arme stances (ff 24r–24v)

- Spada en arme plays (ff 24v–25v)

- Azza stances (f 26r)

- Azza plays (ff 26v–27r)

- (f 27v – blank page)

- Mounted combat plays (ff 28r–32v)

- Spear vs. cavalry (f 33r)

- Mounted combat play (f 33v)

- Sword vs. dagger plays (ff 34r–35r)

- Exotic poleaxes (f 35r)

- Closing (f 35v)

Florius de Arte Luctandi (Mss. Latin 11269)

[edit]Mss. Latin 11269 | |

|---|---|

| Bibliothèque nationale de France | |

Folia 14v–15r | |

| Date | after 1409 |

| Place of origin | Paris, France (?) |

| Language(s) | Renaissance Latin |

| Scribe(s) | Unknown |

| Author(s) | Fiore dei Liberi |

| Illuminated by | Unknown |

| Material | Parchment, with a pasteboard leather cover |

| Size | 44 folia, 255×195 mm |

| Format | Double-sided; two illustrations per side, with text above |

| Script | Bastarda |

| Exemplar(s) | Pisani Dossi Ms. |

| Other | Catalog listing |

The Mss. Latin 11269, titled Florius de Arte Luctandi in a 17th-century script, was rediscovered in the holdings of the Bibliothèque nationale de France by Ken Mondschein in 2008.[23][34] Any preface it once possessed is missing from the current form of the manuscript; it consists of 44 folios with two pairings per page, and is the only copy of Fiore's treatise whose illustrations are fully painted. Unlike Fiore's other works, this manuscript is written entirely in Latin; its descriptions are cast in couplets and quatrains similar to the Pisani Dossi Ms. This manuscript is generally referred to as either the Florius or the Paris. Mondschein speculates that this was a presentation copy made for Lionello d'Este.[35]

The known provenance of the Mss. Latin 11269 is:[23][34]

- Written in the early 15th century, probably after the completion of Flos Duellatorum in 1409.

- Ca. 1635 – rebound by a master papermaker who worked at the Puy-moyen mill for Sieur Janssen.

- before 1712 – in the collection of Louis Phélypeaux, marquis de Phélypeaux. Donated by him to the Bibliothèque du Roi, where it was labeled Florius de Art Luctandi.

- 1712–present – held by the Bibliothèque du Roi/Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The contents of the Mss. Latin 11269 are as follows:

- Title page (f 1r)

- Segno with 7 swords and animal virtues (f 1v)

- Mounted combat (ff 2r–5v)

- Spear vs. cavalry (ff 6r–6v)

- Lanza plays (ff 6v–7v)

- Plays of spear with dagger and two clubs with dagger (f 8r–8v)

- Azza plays (ff 8v–10r)

- Spada a un mano (ff 10r–12r)

- Spada a dui mani stances (ff 12v–13v)

- Spada a dui mani wide plays (ff 14r–15v)

- Spada en arme plays (ff 16r–17v)

- Spada en arme stances (f 18r)

- Spada en arme plays (ff 18r–18v)

- (f 19r – blank page)

- Spada en arme stances (f 19v)

- Sword vs. dagger plays (ff 20r–20v)

- Daga intro (f 21r)

- Daga plays (ff 21v–25v)

- Spada a dui mani wide play (ff 26r)

- Spada a dui mani close plays (ff 26r–30v)

- Daga plays (ff 31r–38r)

- Abrazare stances (f 38v)

- Abrazare plays (ff 39r–42v)

- Daga plays (ff 43r–44r)

- Closing (f 44r)

Codices LXXXIV and CX

[edit]The Codex LXXXIV (or Ms. 84) is mentioned in the 1436 and 1508 catalogs of the Biblioteca Estense in Ferrara, but disappeared some time in the 16th century. It consisted of 58 folios bound in leather with a clasp, with a white eagle and two helmets on the first page. The Codex CX (or Ms. 110) is also mentioned in the 1436 and 1508 catalogs of the Biblioteca Estense, but not in later inventories. It consisted of 15 small-format folios on unbound parchment, and was written in two columns.[23][36]

The contents and current whereabouts of these copies of the Flower of Battle are unknown. It is possible that these listings refer to manuscripts listed above, though none currently possess the correct number of folios or match the physical descriptions.

References

[edit]- ^ This estimated birth date is derived from Fiore's statement that in 1404 he had been studying the art of arms for "a good 40 years and more", assuming that he would have begun being instructed in martial arts at about the age of ten as was general practice among the nobility at the time; see Mondschein (2011), p 11. MS M.383 fol. 2r has: Che io fiore sapiando legere e scrivere e disignare e abiando libri in questa arte e in lei ò studiado ben XL anni e più, anchora non son ben perfecto magistro in questa arte. "So that I, Fiore, knowing how to read and write and draw and having books about this art which I have studied for a good 40 years and more, even now I am not a perfected master in this art." (the same statement incidentally illustrates that Fiore owned a collection of "books in this art" made in the 14th century which have not come down to us)

- ^ See below for the claim by Blengini di Torricella that he was alive until at least 1420.

- ^ after the early-14th-century RA Ms. I.33 and the late-14th-century GNM Ms. 3227a, and roughly contemporary with the French Le jeu de la hache; comparable texts from the Asian traditions of swordsmanshipt do not appear prior to the 16th century, e.g. Jixiao Xinshu, Muyejebo.

- ^ a b c Liberi, Fiore dei (ca.1400s). Fior di Battaglia [manuscript]. Ms. M.383. New York City: Morgan Library & Museum. ff 1r–2r.

- ^ a b c Liberi, Fiore dei (ca.1400). Fior di Battaglia [manuscript]. Ms. Ludwig XV 13 (ACNO 83.MR.183). Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ff 1r–2r.

- ^ a b c Liberi, Fiore dei (1409). Flos Duellatorum [manuscript]. Pisani Dossi Ms. Italy: Private Collection. f 1rv.

- ^ He is never given such a surname in any contemporary records of his life, and the term only appears when introducing his family in his own treatises. See Malipiero, p 80.

- ^ a b c Mondschein (2011), p 11.

- ^ Howe, Russ. "Fiore dei Liberi: Origins and Motivations". Journal of Western Martial Art. Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences, 2008. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Giusto Fontanini. Della Eloquenza italiana di monsignor Giusto Fontanini, p. 274, at Google Books, vol. 3 (in Italian). R. Bernabò, 1736. pp 274–276.

- ^ Gian Giuseppe Liruti. Notizie delle vite ed opere scritte da' letterati del Friuli, p. 27, at Google Books, vol. 4 (in Italian). Alvisopoli, 1830. p 27.

- ^ Novati, pp 15–16.

- ^ Malipiero, p 80.

- ^ Pisani-Dossi 2a.4: quorum omnium deo dante plenariam notitiam sum adeptus expertorum magistrorum exemplis multifariis et doctrina ytalicorum ac alamanorum et maxime a magistro johane dicto suueno, qui fuit scholaris magistri Nicholai de toblem mexinensis diocesis, ac etiam a pluribus principibus ducibus marchionibus et comitibus et ab aliis innumerabilibus et diuerssis locis et prouinciis. "all of which knowledge, God granting, I acquired from the numerous lessons and teachings of Italian and German expert teachers, and mostly from master John, called Suvenus, who was a student of master Nicholas of Toblem in the Mexinensian diocese, and also from several princes, margraves and counts and from other countless and diverse places and provinces" (mexinensis diocesis having been variously identified as either Metz or Meissen). Cvet, David M. "A Brief Examination of Fiore dei Liberi's Treatises Flos Duellatorum & Fior di Battaglia". Journal of Western Martial Art. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d'Elsa." Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 – 1550. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Leoni, p 7.

- ^ a b "GALEAZZO DA MANTOVA (Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli, Galeazzo Gonzaga) Di Mantova. Secondo alcune fonti, di Grumello nel pavese." Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 – 1550. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ "LANCILLOTTO BECCARIA (Lanciarotto Beccaria) Di Pavia. Ghibellino. Signore di Serravalle Scrivia, Casei Gerola, Bassignana, Novi Ligure, Voghera, Broni." Archived 16 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 – 1550. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ a b Malipiero, pp 94–96.

- ^ Fiore his masters and his students. Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ This is the only point when both men are known to have been in Perugia at the same time; Verde died soon after this in 1385. See Fiore his masters and his students. Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau. in English and "PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d'Elsa." Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. and "PIETRO DELLA CORONA (Pietro Cornuald) Tedesco. Signore di Angri." Archived 10 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 – 1550. in Italian. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Malipiero, p 85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Easton, Matt. "Fiore dei Liberi – Fiore di Battaglia – Flos Duellatorum". London: Schola Gladiatoria, 2009. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Malipiero, pp 85–88.

- ^ Malipiero, pp 55–58.

- ^ a b Mondschein (2011), p 12.

- ^ Malipiero, p 97.

- ^ Fiore states in the preface to the Pisani Dossi Ms. that he had studied combat for fifty years, whereas the comparable statement in the Ms. M.383 and Ms. Ludwig XV 13 mention the slightly shorter "forty years and more".

- ^ Zanutto, pp 211–212.

- ^ "In 1904, a historical work by Francesco Novati, Director of the Academy in Milano and Gaffuri, Director of the graphical institute in Bergamo was published… These two prominent scholars uncovered documents, found in different archives, …Rules for Fencing were printed by Fiore dei Liberi in 1420… And how could then dei Liberi have taught fencing lessons in Paris in 1418?" (translated from Norwegian by Roger Norling). See Blengini, di Torricella C. A. Haandbog i Fægtning med Floret, Kaarde, Sabel, Forsvar med Sabel mod Bajonet og Sabelhugning tilhest: Med forklarende Tegninger og en Oversigt over Fægtekunstens Historie og Udvikling. 1907. p 28.[full citation needed]

- ^ See "Curatorial description". CORSAIR Collection Catalog. Morgan Library & Museum. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Anglo, Sydney (2000). The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-300-08352-1.

- ^ dei Liberi, Fiore; Rubboli, Marco; Cesari, Luca, Flos Duellatorum: Manuale di Arte del Combattimento del XV Secolo, Rome: Il Icherio Initiative Editoriali, ISBN 88-8474-023-1 (2002)

- ^ a b Mondschein, Ken. "Description of the Paris Fiore Ms. (Florius de arte luctandi, BnF Ms. Lat 11269)" (PDF). Historical Fencing Dot Org. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Mondschein, Ken. "On the Art of Fighting". Acta Periodica Duellatorum. Acta Periodica Duellatorum Association. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Novati, pp 29–30.

Further reading

[edit]- Windsor, Guy (2016). Advanced Longsword. Helsinki, Finland: Spada Press. ISBN 978-952-7157-07-7

- Windsor, Guy (2014). The Medieval Longsword. Helsinki, Finland: Spada Press. ISBN 978-952-6819-37-2

- Charrette, Robert N. (2011). Fiore dei Liberi's Armizare: The Chivalric Martial Arts System of Il Fior di Battaglia. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-9825911-7-8.

- Lagomarsini, Claudio (2011). "Un manuale d'armi d'inizio sec. XV: il "Flos duellatorum" di Fiore dei Liberi da Cividale". Studi di Filologia Italiana (in Italian). 69: 257–91.

- Mondschein, Ken (2011). The Knightly Art of Battle. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-160-60607-6-6.

- Windsor, Guy (2011). The Armizare Vade Mecum. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-00-2

- Lancaster, Mark; Berryman, Mark (2010). Primoris. The Rob Lovett Fiore dei Liberi Training System. Wyvern Media. ISBN 978-0-9564871-0-0.

- dei Liberi, Fiore; Leoni, Tommaso. Fiore de' Liberi's Fior di Battaglia, a full translation of the Getty manuscript. 1st ed. Lulu.com (2009). 2nd ed. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press (2012).

- Windsor, Guy (2012). The Medieval Dagger. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-193-7439-03-3

- Richards, Colin (2007). Fiore dei Liberi, 1409: Wrestling & Dagger (in German and English). Arts of Mars Books. ISBN 978-3-9811627-0-7.

- Price, Brian R (2007). Fiore dei Liberi's Sword in Two Hands. Highland Village, TX: The Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-13-3.

- Malipiero, Massimo (2006). Il Fior di battaglia di Fiore dei Liberi da Cividale. Il Codice Ludwing XV 13 del J. Paul Getty Museum (in Italian). Udine: Ribis. ISBN 978-887-44503-5-0.

- Windsor, Guy (2004). The Swordsman’s Companion. Highland Village, TX: The Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-189-1448-41-6

- Easton, Matthew (2003). Fior di Battaglia: The Martial Treatise of Fiore dei Liberi (c.1409). Panda Press. ISBN 978-0-9541633-1-0.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - dei Liberi, Fiore; Rubboli, Marco; Cesari, Luca (2002). Flos Duellatorum. Manuale di Arte del Combattimento del XV secolo (in Italian). Rome: Il Icherio Initiative Editoriali. ISBN 978-88-8474-023-6.

- Rapisardi, Giovani (1998). Fiore de' Liberi Flos Duellatorum – in armis, sine armis equester et pedesta (in Italian). Gladitoria Press.

- Zanutto, D. Luigi (1907). Fiore di Premariacco ed I Ludi e Le Feste Marziali e Civili in Friuli [Fiore of Premariacco and the Military and Civilian Games and Festivals in Friuli] (PDF) (in Italian). Udine: D. del Bianco. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Novati, Francesco (1902). Flos Duellatorum, Il Fior di Battaglia di Maestro Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco [Flos Duellatorum, the Flower of Battle of Master Fiore dei Liberi of Premariacco] (JPG) (in Italian). Bergamo: Instituto Italiano d'Arte Grafiche. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

External links

[edit]- Biography and primary source documents on Wiktenauer.com

Image Galleries

[edit]- High-resolution images of the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 courtesy of the Google Art Project. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- High-resolution images of the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Facsimile of the Pisani Dossi Ms. from Novati, 1902 (PDF file, 42 MB). Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- High-resolution images of the Mss. Latin 11269 courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

Transcriptions and Translations

[edit]- Partial translation of the Ms. Ludwig XV 13 and Ms. M.383 by Matt Easton and Eleonora Durban (inc. transcription). Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Partial translation of the Ms. M.383, Ms. Ludwig XV 13, and Pisani Dossi Ms. by Rob Lovett and Mark Lancaster (inc. transcription). Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Translation of the Pisani Dossi Ms., by Hermes Michelini. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Transcription and French translation of the Ms. Latin 11269 by Charlélie Berthaut. Retrieved 8 May 2013.