Florentia (Roman city)

Florentia (Classical Latin pronunciation: [fɫoːˈrɛnti.a]) was a Roman city in the Arno valley from which Florence originated. According to tradition, it was built by the legions of Gaius Julius Caesar in 59 BC; however, the prevailing hypothesis dates the foundation of the city to the Augustan period (between 30 and 15 BC).[1][2]

Etymology

[edit]Legend attributes the origin of the name Florentia to Florio (a soldier killed on the spot) or to flowers, or to Flora, since it was founded during the Floralia. In reality it is all much simpler, Florentia is a beneaugural name: "may you be florid", "city of floridity". Likewise Potentia, Piacentia, Valentia, Pollentia in other regions of the Empire. Even the ancient name of Granada, for example, was Florentia Illiberitana. The purely benaugural origin of the word Florentia has recently been confirmed by the Accademia della Crusca.[3] Etruscan roots of the term were also sought. Semerano proposed that Florence derived, with a typical paretimological reinterpretation, from a hypothetical birent or birenz with the meaning of "land between the waters, swampy" (in reference to the rivers Mugnone and Affrico), connected with the Akkadian birent.[4] The Etruscan name of the pre-Roman settlement is not known.

Another theory was that it was named originally Fluentia, as it was built between two rivers, which was later changed to Florentia ("flowering").[5]

In fact Florentia has undergone the same lexical transition to modern Italian as flos-floris in "flower", becoming first Fiorenza (medieval Italian) and then Firenze. In foreign languages has remained a diction more faithful to the original Latin (for example Florence in French and English, Florenz in German or Florenţia in Romanian).

First settlements

[edit]

Traces of Copper Age burials have been found in the area of the historical center of Florence between Piazza della Signoria and Piazza della Repubblica.

With the Iron Age the Florentine area is affected by Villanovan settlements, which are evidenced by the burials of the eighth century BC found between 1892 and 1906 in the historic center, towards Via de 'Vecchietti and under today's ex-Gambrinus, in Piazza della Repubblica.

The area where the city was built was probably the one where it was easier to ford the Arno because of the shorter distance between the two banks. Moreover, the position on the watershed between the confluence of the tributaries of the Arno, Mugnone and Affrico, gave the area a slightly higher altitude than the rest of the plain, probably marshy.

The area was interested by a continuity of settlement also in the following epoch, since it assured the possibility of connection of the inner Etruria with the city of Fiesole. It is probable that the Etruscans of Fiesole made a stable crossing of the river with a wooden footbridge or a ferryboat, at the point where the Arno narrows (the area of Ponte Vecchio), perhaps to control militarily such a strategic point that is located between the high course of the Arno, the Valdarno of Arezzo, and the low course that leads to Pisa and the sea. From the findings found on the bottom of the Arno (stone slabs) we can deduce the size and type of the walkway: it was in fact in wood mounted on stone piers.[6]

After the Roman expansion in Etruria and in the Po Valley, the settlement of the ford probably grew, also because the Via Cassia, for a certain period, crossed the Arno right in the Florentine area, perhaps in the area of the current Ponte Vecchio.

Excavations have identified Roman civic buildings and a wall circle on the side of the 1333 wall, demolished during the 19th century destruction to make way for the ring road.

From today's Piazza Donatello in an easterly direction towards the Affrico torrent there was probably an Etruscan-Roman urban agglomeration which was the expansion towards the Arno of the Roman Fiesole in defense of the Etruscan bridge which crossed the Arno at the height of today's Rovezzano, already mentioned by medieval historians such as Giovanni Villani.

l'antico ponte de' Fiesolani, il quale era da Girone a Candegghi [oggi Girone e Candeli, frazioni fiorentine] : e quella era l'antica e diritta strada e cammino da Roma a Fiesole

— G. Villani Nuova Cronica Lib.II Cap. XX

This agglomeration was perhaps an outpost built at the time of the civil war between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla won by the party of the latter who then provided the conquest of the colony fiesolana favorable to the party of Mario.

The decadence of Fiesole after 80 B.C., gave, probably, a new impulse to the settlement in the valley. After Catilina's coup, which ended tragically in 62 B.C. in Pistoria (Pistoia), which saw again the Etruscan municipalities confederated against Rome, the Etruscan-Roman city acquired more and more strategic value given its geographical position between the river and the hill. In the same year Caesar ordered the construction of a castrum to control the city of Fiesole because of the large number of catilinarians

Colony foundation

[edit]

Uncertain is the date of the foundation of the colony of Florentia that over time has been variously attributed, apart from mythological references,[7] to Sulla,[8] Julius Caesar and Augustus. Historians agree in dating to 59 B.C. the foundation of the Roman colony of Florentia. The Liber Coloniarum attributes to a lex Iulia agris limitandis metiundis, wanted by Gaius Julius Caesar, the will to give birth to a new urban system in this part of the Arno valley, where it crossed the river at the height of Ponte Vecchio.

The actual layout of the city and the centuriation of its territory dates back to the second triumvirate,[9] to be able to settle veterans by land allocation. It was built in the style of an army camp with the main streets, the cardo and the decumanus, intersecting at the present Piazza della Repubblica.

As usual in the foundation of new settlements, the city and its surroundings were defined according to a precise plan that involved the urban layout and agricultural territory. The city followed the ideal rule of orientation according to the cardinal axes, while the surrounding territory was arranged taking into account the hydraulic conformation, rotating the axes as convenient. From the aerial photos, even today, it is possible to distinguish the cardo massimo oriented north–south (from Via Roma to the Arno), and the decumanus maximus oriented east–west (the current path of Via Strozzi and Via del Corso) which intersected at the height of the current Piazza della Repubblica seat of the Forum of the city and the Campidoglio, surrounded by the main public buildings and temples. During the centuries of the Empire in fact, the city was enriched with all those buildings and infrastructures that characterized Roman cities: an aqueduct (from Monte Morello), two baths, a theater and an amphitheater, built outside the walls, as was customary.[10]

Roman buildings

[edit]

According to Guicciardini, the Romans who built Florentia were:

[...] non gente inutile e seditiosa ma uomini militari [...] che con la virtù delle arme e felicità delle vittorie meritorono questi premii [...]

To the god Mars, according to the military tradition, was naturally dedicated the main temple of the city always identified with the Baptistery, the change of the patron was also highlighted by Dante in the Inferno:

I' fui de la città che nel Battista mutò il primo padrone

— Dante Inf. XIII, 143

Lorenzo Ghiberti in his 15th century Chronicle comments the following:

Dunque dovrem nei sempre rammentarci che qui Marte aveva altari ed incensi? Dove adesso giganteggia il quadrangolar Campanile a lato della maestosa Cupola del Duomo, poco presso v'ebbe Gradivo il suo tempio che ancora vi esiste.

Gradivus (he who goes) was one of the various names or attributes of the God Mars, but the same author-artist points to the Baptistery as the old Christianized pagan temple:

L'elegante tempio di Marte, ammirazione ancora dei presenti quantunque a fronte della mole sublime del Duomo, presenta i suoi lati ottagoni[...] [così] che ovunque avesse spirato il vento dovesse stendersi il braccio ferreo del Dio guerriero.

The city, in the meantime was expanding in all directions, to the north in the religious area of the Temple of Mars and then the ancient church of Santa Reparata, south to the river and even beyond the Arno where he settled a colony of Syrian traders within which developed the first nucleus of Christians in the city.

But more than anything else, the city extended eastwards, as shown by the foundations of civil buildings and remains of baths from the imperial period, discovered during excavations in Piazza della Signoria, but especially in the slope leading to Piazza San Firenze below. On this natural slope the Romans had built the Theatre of the city (1st century A.D.), which emerges from under Palazzo Vecchio and Palazzo Gondi. Where for a long time the Tribunal had its seat there was probably the skene and towards Piazza della Signoria the steps for the public. Not far away, outside the walls, traces of a Temple of Isis (2nd century A.D.) were found, excavated between October and December 2008.

The foundations of the walls, with defensive towers, were found under via del Proconsolo and according to the most recent excavations date back to the period between 30 and 15 B.C. They were two meters thick on average and surrounded an area of about 20 hectares. Other Roman remains have been found under the nearby Palazzo dell'Arte dei Giudici e Notai. Under the church of Santa Felicita there is a stretch of the Via Cassia[citation needed].

One of the few structures actually still recognizable in Roman brick is that of the Amphitheater, which was outside the castrum Caesar, in the current medieval district of Santa Croce.

The first who made an in-depth study of this structure was the scholar Domenico Maria Manni who in 1746 published the book Notizie istoriche intorno al Parlagio ovvero anfiteatro di Firenze.

Surrounded by a road that, appropriately, was called via Tórta since the Middle Ages, the amphitheater of Florentia was of medium size (about 20,000 seats, against 87. 000 of the Colosseum), perhaps to testify the meagreness of the local population, but perfectly recognizable in its load-bearing structures, even if here, as in other cases (e.g. the amphitheater of Lucca), the superimposition of medieval houses has closed the ancient arches (the fornices) and exploited all the spaces of the small amphitheater.

In the nineteenth century some of the names of the streets around Piazza della Repubblica were chosen on the basis of the Roman findings in the underground: via delle Terme, via del Campidoglio, via di Capaccio (i.e. of Caput Aquae, the outlet of the aqueduct, which Nuova Cronica by Giovanni Villani is assigned to Macrino, general of Caesar).

Surrounding territories

[edit]Towards the south Florentia bordered with an area of villas and thermal baths, an area that still bears the name of Bagno a Ripoli, a municipality of Chianti, contiguous to today's city, but in Roman times a place of leisure and rest as can be seen from the discovery of villas and thermal complexes. But the most interesting evidence of Roman Etruria is the archaeological area of Fiesole, with the theater almost intact and the baths, already from the Republican era, which were embellished under the emperors Claudius and Septimus Severus.

To the north of the city passed the Via Cassia and as in many other cases in the cities of Roman origin, some fractions have taken their name from the distance, in Roman miles, from the city, in the case of Florentia, in the north-west direction are found, from the third mile on Terzolle (and also Le Tre Pietre), Quarto, Quinto, Sesto Fiorentino and Settimello.

The medieval city did not immediately overlap the ancient Florentia, still in '400 Guicciardini testifies to the still visible remains of Florentia.

[...] che ancora appariscono dagli edifici fatti da loro [i romani] fanno certo inditio che è principii de la città fussino assai magnifici, maxime el Tempio di Marte [...] e gli aqueducti fatti più per pompa e imitatione di Roma che per necessità [...]

Therefore, a city more and more important Florentia with Adriano was caught up from the way Cassia and united it to the road net of the empire. In 285 AD, under Diocletian it was raised to Corrector Italiae that is capital of Tuscia, the northern Etruria and of umbria and was preferred to older towns like the Fiesole, Arezzo and Perugia.

Centuriation

[edit]Like all Roman colonies, also for Florentia was performed the centuriation of the surrounding territory and in particular of the flat and presumably marshy area west of the city that was simultaneously reclaimed in order to obtain plots of land to be assigned to veteran legionaries. The traces of the centuriation are still visible, for example on the IGM cartography (even if they are even more visible observing the editions up to the 50's, before the urban expansion attacked in a relevant way the plain between Florence and Campi and beyond). The geometric regularity of the fields in the few areas not yet urbanized is a legacy of the vast Roman land reclamation, connected to the colony of Florentia, which extended over the entire plain between Florence and Prato, reconnecting to the centuriation of Pistoriae (Pistoia).

From the cartographic results it was possible to reconstruct the scheme of the centuriation as a whole, made up of squares of about 710 meters of side[11]

Christian Florentia

[edit]At the time of the decline of the Roman Empire, Florentia was a thriving city thanks to trade, the Arno, as testified by Strabo, was a river still navigable and at the height of today's Piazza de 'Giudici (others place the port in the next piazza Mentana) there were docks, more or less where today there is the Rowing Club Florence, for loading and unloading of goods in the area that is still called the Customs.

But the economic well-being inevitably attracted also the raids of the barbarian kings who raged in Italy: in 405 or 406 it was besieged by the Ostrogoths of Radagaiso, and again in 542 by the same Ostrogoths this time commanded by king Totila.[12]

With Constantine, Christianity had become the state religion, but the affirmation of the Christian religion in Florentia was neither easy nor painless.

The suburbs of Oltrarno, where lived a large community of oriental traders, especially Syrians, were the cradle of the new religions, both Mithras and the Egyptian cult of the goddess Isis (a temple dedicated to her was in Piazza San Firenze) and Christianity. These villages were however a suburb of the city, as the noble Guicciardini writes inhabited by vile people, the center of the city, however, was in the hands of patrician families linked to the old religion.

The oriental religions of a mysterious type because of the hold they had on the "vile people" worried the Florentine patriciate, but the greatest danger was the influence that the religious leaders of Christianity had on the crowds.

Florentia counted so the first martyrs of the city, the bishop of Syrian origin Miniato (3rd century) was one of the most famous whose bones are buried in the church of San Miniato al Monte dedicated to him after his martyrdom occurred in the Amphitheater. Already in the 4th century there is a documented evidence of a bishop Felice, even if a real diocesan organization in Florence was possible only a few decades later with San Zanobi (337 - 417).

With the continuation of foreign invasions, from the Byzantines to the Lombards, the Roman Florentia declined. Categoria:Chiarire

Disappearance of the Roman Florentia

[edit]

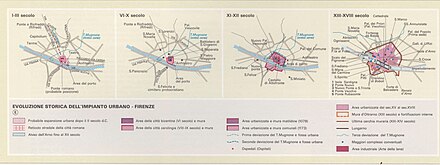

Between the first and second century the city was fully part of the vast and organized commercial system of the Roman Empire, thanks to the river port, which allowed trade with Pisa. Archaeological excavations have documented, among other things, trade with Gaul and Africa. In the late empire the city was involved in the general crisis, also economic, of the empire. In the sixth century, with the Greek-Gothic wars and the Lombard conquest, the situation of general decline worsened, with the interruption of commercial traffic and the general impoverishment of the city.[13] Between the sixth and the eighth century, probably, came into crisis even the urban structure of the city, with the demographic decline, the abandonment of the outer areas and the general and progressive degradation of all buildings and walls.

Beginning in the eleventh century, new building growth left few vestiges of the past. The remains of the theater, the baths, the amphitheater and other buildings were incorporated into new buildings or used as foundations. The Forum Square was densely built up and later became part of the Ghetto, around Mercato Vecchio.

With the Savoy arrangement of the Piazza del Mercato Vecchio, at the time of Florence as the capital of Italy (the so-called Risanamento), the Ghetto was demolished and with it the most important remains of the Capitol and the Forum disappeared. Of the findings made during this work, only cursory surveys were made and the evidence collected by the architect Corinto Corinti.

Roman art in Florence

[edit]Almost all of the Roman art present in Florence today, apart from a few rare examples of sarcophagi mentioned above, did not belong to Florentia, but was brought from Rome at the time of the Medici and Lorena families. From Rome come the collection of ancient statues that decorate the Loggia dei Lanzi, the Uffizi Gallery, Palazzo Pitti and the Boboli Gardens, including the obelisk. The city's other Roman obelisk, located in Piazza Santa Trinita in front of the church of the same name, comes from the Baths of Caracalla, a gift from Pope Pius IV to Grand Duke Cosimo I. The Roman collections of the National Archaeological Museum have various origins and were mostly brought to the city between the nineteenth and twentieth century, with the exception of the materials collected in the so-called "courtyard of the Florentines".[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ De Marinis, G. Becattini M., Firenze ritrovata, in "Archeologia viva", XIII, n.s. 48, nov.-dic.1994, pp. 42-57

- ^ F.Castagnoli, La centuriazione di Florentia, in «Universo», XXVIII, 1948.

- ^ "Perché Firenze si chiama così: la Crusca risponde - La Nazione". Firenze - La Nazione - Quotidiano di Firenze con le ultime notizie della Toscana e dell’Umbria. 18 April 2016.

- ^ G. Semerano: Le origini della cultura europea

- ^ Leonardo Bruni, History of the Florentine People I.1, 3

- ^ Museo dei Ragazzi, Florentia

- ^ Particolarmente mirabolante è quella riportata da Raffaello Gualtierotti nel suo, Della descrizione del regale apparato fatto nella nobile città di Firenze per la venuta, e per le nozze della serenissima madama Cristina di Lorena moglie del serenissimo don Ferdinando Medici terzo gran duca di Toscana, stampata a Firenze nel 1589, ed in cui scrive: "... la fondazione della prima città di Firenze, della quale si è havuto in diversi tempi molte dubitazioni & opinioni differenti: perciocché alcuni hanno voluto, che già fusse fondata, e di abitanti ripiena, dal più antico Ercole detto il libico [...] per la toscana passando ci fondasse città, e rasciugasse l'acque dannose, e particolarmente aprisse il corso a l'acque stagnanti del fiume d'Arno, facendo la rottura della Gonfolina: & alla città di Firenze desse principio..."

- ^ Tra i primi da Francesco Guicciardini che nel suo trattato delle Cose Fiorentine (1441) affronta il problema dell'origine di Florentia, anche se in modo piuttosto contraddittorio, scrive: "...tengo per certo che non da quelli Romani che Sylla o altri aveva mandato a Fiesole, ma che nel luogo medesimo dove ora è Firenze fussi mandata una colonia che edificò questa città...", ma poi, più avanti ..."né dubiterei dire che questa colonia, mandata da Roma nel luogo proprio dove è ora Firenze, fussi più presto mandata da Sylla che da altri..."

- ^ F.Castagnoli, op. cit., 1948.

- ^ Caniggia, Gianfranco. "A Structural Reading of Florence". HEIA-FR - Architecture. HES-SO channels. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ F.Castagnoli, La centuriazione di Florentia, in «Universo», XXVIII, 1948, pp. 361-368.

- ^ Paolino di Milano, Vita Ambrosii, 50 (per l'assedio di Radagaiso, che comunque non riuscì ad espugnare la città per l'arrivo di Stilicone); Procopio di Cesarea, De Bello Gothico, III,5 (per l'assedio di Totila, che anche in questo caso non riuscì ad espugnare la città).

- ^ R. Francovich, F. Cantini, E. Scampoli, J. Bruttini, La storia di Firenze tra tarda antichità e medioevo. Nuovi dati dallo scavo di via de' Castellani, in "Annali di storia di Firenze",II,2007.

- ^ Cortile dei Fiorentini

Bibliography

[edit]- Discorsi di Vincenzo Borghini, Dell'origine della Città di Firenze, (1584), Volume 1, a cura di Domenico Maria Manni, Società tipografica de'Classici italiani, 1808

- D. M. Manni, Notizie istoriche intorno al Parlagio ovvero Anfiteatro di Firenze, Firenze 1746

- G. F. Gamurrini, Rapporto del Regio Commissario, commendator Gamurrini (materiali dal tempio di Iside), in Notizie degli Scavi 1886, p. 177

- L. A. Milani, Pozzo praticabile presso le Terme e il Campidoglio nel foro Fiorentino, in Notizie degli Scavi 1893, pp. 493–496

- D. Fraschetti, Il Tempio di Marte e la Chiesa di S. Giovanni Battista, in Arte e Storia 27, 1908, p. 182 sgg.

- A. Guerri, Cenni topografici su Firenze romana, in Illustratore Fiorentino n.s. VI.1-5, 1909, pp. 94–99

- Corinti C., Degli avanzi del teatro di Firenze romana, in Atti della Società Colombaria, Firenze. 1924

- Maetzke G., Florentia (Firenze). Regio VII - Etruria, Italia romana: Municipi e Colonie, I, 5, Roma. 1941

- Hardie C., The Origin and Plain of Roman Florence, Journal of Roman Studies 1965, LV, pp. 122–140

- F. Chiostri, L'acquedotto romano di Firenze, Firenze 1973

- E. Mensi, La fortezza di Firenze e il suo territorio in epoca romana, Firenze 1991

- P. Degl'Iinnocenti, Le origini del Bel San Giovanni. Da tempio di Marte a battistero di Firenze, Firenze 1994

- G. Capecchi (a cura di), Alle origini di Firenze. Dalla Preistoria alla città romana, Firenze 1996.

- Martini F., Poggesi G., Sarti L. (a cura di), Lunga memoria della piana, L'area fiorentina dalla preistoria alla romanizzazione, Guida alla mostra, Firenze. 1999

- F. Salvestrini, Libera città su fiume regale. Firenze e l'Arno dall'Antichità al Quattrocento, Firenze 2005

- Francesco Maria Petrini, Florentia Ostrogota, in V. D'Aquino – G. Guarducci – S. Nencetti – S. Valentini (edd.), Archeologia a Firenze: Città e Territorio: Atti del Workshop. Firenze, 12-13 Aprile 2013, “Archeologia a Firenze: città e territorio”, Oxford 2015, pp. 225–246.