Searches for Noah's Ark

Searches for Noah's Ark have been reported since antiquity, as ancient scholars sought to affirm the historicity of the Genesis flood narrative by citing accounts of relics recovered from the Ark.[1]: 43–47 [2] With the emergence of biblical archaeology in the 19th century, the potential of a formal search attracted interest in alleged discoveries and hoaxes. By the 1940s, expeditions were being organized to follow up on these apparent leads.[3][4]: 8–9 This modern search movement has been informally called "arkeology".[5]

In 2020, the young Earth creationist group the Institute for Creation Research acknowledged that, despite many expeditions, Noah's Ark had not been found and is unlikely to be found.[6] Many of the supposed findings and methods used in the search are regarded as pseudoscience and pseudoarchaeology by geologists and archaeologists.[7][8]: 581–582 [9]: 72–75 [10]

Antiquity

[edit]

At the end of the Genesis flood narrative, when the flooding subsides, the Ark is said to come to rest "on the mountains of Ararat."[11] The Book of Jubilees specifies a particular mountain, naming it "Lûbâr".[12] The Torah does not describe any particular holiness about the Ark, and so little attention is given to its fate after Noah's departure.[13]

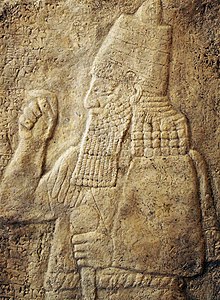

According to the Talmud, the Assyrian king Sennacherib found a beam from the Ark and, reasoning that it was the god who delivered Noah from the flood, fashioned the wood into an idol.[14] This expands upon the biblical account of Sennacherib worshiping in the temple of Nisroch, interpreting the god's name to be derived from the Hebrew word neser ("beam").[15] A Midrash regarding the Book of Esther says that the gallows erected by Haman was built using a beam from the Ark.[16][13]

Opinions on the location of "the mountains of Ararat" have varied since antiquity. Interpretations of the Noah story were influenced by the Armenian flood myth about Masis, and the Syrian version about Qardu in Corduene, until these locations became conflated.[17]: 336 The targumim for Genesis 8 interpret "Ararat" as "Qadron" and "Kardu" (i.e., Corduene).[18][19][20]: 233 In his recounting of the Flood, Josephus seeks to link the story of Noah to the Sumerian flood myth as described by Berossus, Hieronymus of Cardia, Mnaseas of Patrae, and Nicolaus of Damascus, thereby placing Noah's Ark on a mountain in Armenia, where he says relics from the ship are exhibited "to this day."[1]: 43–47 [21]: 329–330 However, Josephus later describes Carrhae as the location of the Ark, again claiming that the locals would show the remains to visitors.[22]: 237 Jerome of Stridon translated "Ararat" as "Armenia" in the Vulgate,[23] whereas the Armenians themselves associated Noah's Ark with Corduene until the 11th century.[17]: 336

In the early Christian church, stories about the remains of Noah's Ark were regarded as evidence that the ship had been located, identified, and preserved in some form. This became useful in Christian apologetics for affirming the events of the Pentateuch as fact.[4]: 6–7 Epiphanius of Salamis wrote: "Thus even today the remains of Noah’s ark are still shown in Cardyaei."[24]: 48 [25]: 75–77 Similarly, John Chrysostom proposed to ask non-believers: "Have you heard of the Flood—of that universal destruction? That was not just a threat, was it? Did it not really come to pass—was not this mighty work carried out? Do not the mountains of Armenia testify to it, where the Ark rested? And are not the remains of the Ark preserved there to this very day for our admonition?"[25]: 78 However, with the widespread adoption of Christianity in Europe, the apologetic value of Ark relics diminished, as there were far fewer non-believers to persuade.[4]: 7

By the 5th century, a legend had arisen that Jacob of Nisibis scaled a mountain in search of Noah's Ark. As related by Faustus of Byzantium, Jacob and his party traveled to the mountains of Armenia, and "came to Sararad mountain which was in the borders of the Ayraratean lordship, in the district of Korduk'." Near the summit, an angel visited him in his sleep, instructing him to climb no further. In consolation, the angel provided Jacob with a board taken from the Ark. Jacob brought the artifact back to the city, which is said to have preserved the relic ever since.[2] Agathangelos relates a similar story, although not directly related to the Ark, in which the 3rd century Armenian king Tiridates scales Masis and brings back eight rocks to use in the foundation of new churches.[26]: 35

Middle Ages and early modern period

[edit]In the 7th century, the Etymologiae states "Ararat is a mountain in Armenia where the historians testify that the Ark came to rest after the Flood."[citation needed] The Quran describes the Ark landing on "al-jūdī," which is understood to refer to Qardu, now known as Mount Judi.[27]: 298 [28][29]: 683–684 Heraclius is reported to have scaled Mount Judi to visit the site of the Ark in either 628 or 629.[30]: 78 One legend claims that Omar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb removed the Ark from a site near Nisibis and used the wood to construct a mosque.[31]: 284

Despite the longstanding association of Armenia with Ararat in Western Christianity, Christians in Armenia did not adopt the idea of Masis as the landing site of the Ark until the arrival of Crusaders in the late 11th century. Thereafter, Armenians adopted the Western identification of Masis as "Mount Ararat", and relocated the Jacob of Nisibis legend to that peak.[26]: 36 The angel's admonition to Jacob became a new explanation for the pre-Christian taboo against climbing the sacred mountain.[26]: 37 [32]: 202–203 [33]: 214 [34]: 100 Regardless of this cultural impediment, other travelers claimed the summit was physically inaccessible, due to the permanent snow line and an abundance of precipices.[35]: 25–26 [36][37]: 187

Late medieval reports from Ararat often mentioned the survival of Ark fragments, but there was less consensus about whether the vessel itself survived. Petachiah of Regensburg simply declared "the Ark is not there, for it has decayed."[38]: 49 Just over a century later, however, Hayton of Corycus claimed that "on the mountain's summit something black is visible, which people say is the Ark."[36]

Sir Walter Raleigh objected to the view that the Ark landed in Armenia, arguing that the Armenian mountains could merely be a sub-range of "the mountains of Ararat." He proposed a definition of "Ararat" that would encompass the Taurus, Caucasus, Sariphi, and Paropamisus mountain ranges. This interpretation would allow the Ark to have landed to the east of Mesopotamia, which Raleigh felt was necessary to explain why Noah's descendants migrated to Shinar "from the east" in Genesis 11:2.[39]

19th century

[edit]

The first recorded ascent of Ararat was led by Friedrich Parrot in 1829.[40]: iv In his account of the expedition, Parrot wrote that "all the Armenians are firmly persuaded that Noah's Ark remains to this very day on the top of Ararat, and that, in order to preserve it, no human being is allowed to approach it."[40]: 162

James Bryce scaled Ararat in 1876.[41]: 293–294 On his ascent, he discovered "a piece of wood about four feet long and five inches thick, evidently cut by some tool, and so far above the limit of trees that it could by no possibility be a natural fragment of one." Bryce cut off a portion of the wood to keep, and later argued that it might plausibly be a remnant of Noah's ark. Although he admitted another explanation for the wood had occurred to him, he determined that "no man is bound to discredit his own relic."[41]: 280–281

New Zealand Herald hoax

[edit]On 26 March 1883, an avalanche was reported at Mount Ararat which destroyed several villages.[42][43][44][45] As an April Fools' Day joke, George McCullagh Reed, writing as "Pollex" for his opinion column in the New Zealand Herald, claimed that the avalanche had revealed the remains of Noah's Ark.[46][47][48]: 59–60 Reed's story largely takes the form of a dispatch supposedly received from the Levant Herald in Constantinople, which he believed to have ceased operations several years earlier; in fact the paper had by that time relaunched as the Eastern Express.[49] The report describes the findings of "Commissioners appointed by the Turkish Government", including a nonexistent English scientist named "Captain Gascoyne", which had already been submitted to Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the German ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. A reference to "an enterprising American traveller" seeking to purchase the Ark for exhibition in the United States was intended by Reed to be recognized as P. T. Barnum.[46][50]

Over the next several months, Reed's prank was picked up by newspapers around the world.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58] While some publications presented the story tongue-in-cheek, others uncritically reprinted much of what Reed originally wrote, attributing it (as he had) to a correspondent in Constantinople. On 24 November, Reed wrote another column apologizing for the hoax and expressing amusement that the story had spread so far:[50][59]

"From the London Times to the Glasgow Herald, from the Leeds Mercury to the Pall Mall Gazette, through all the principal metropolitan and provincial journals in Britain and all over America my friend Captain Gascoyne and our Ark have been honoured with being handed on; but the editor of the Prophetic Messenger is to be credited with the greatest zeal in establishing the authenticity."[50]

Despite this retraction, the story has continued to be circulated, often referencing the Prophetic Messenger article, which Tim LaHaye and John D. Morris called "the most complete and accurate account of the discovery."[60]: 56–63 [61][62]: 111 [63][64]

John Joseph Nouri

[edit]

John Joseph Nouri claimed to have discovered Noah's Ark on the summit of Mount Ararat in April 1887.[65]: 164–165 [66]: 39 Little else about him is known for certain. He was born in Baghdad in 1865, and in 1885 he was consecrated as an archdeacon in the Chaldean Catholic Church. During his tour of the United States, he attracted attention with his long list of formal titles: "His Pontifical Eminence, the most Venerable Prelate, Monseignior. The Zamorin Nouri. John Joseph Prince of Nouri, D.D, LL., D. (By Divine Providence.) Chaldean Patriarchal Archdeacon of Babylon and Jerusalem, Grand Apostolic Ambassador of Malabar, India and Persia. The Discoveror of Noah's Ark and the Golden Mountains of the Moon. The Sacred Crown's Supreme Representative General of the Holy Orthodox, Oriental, Patriarchal Imperiality of 900,000,000 People of Asia. The First Universal Exploring Traveler of One Million Miles."[67] Those who knew him, including J. O. Kinnaman, Frederick G. Coan, and John Henry Barrows, regarded him as a charismatic, well-traveled scholar who spoke multiple languages.[66]: 41–45 [65]: 163 [68]: 299–300

In 1893, Nouri attended the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago.[65]: 163–164 By his account, he was invited to the event to speak about his encounter with the Ark, although the official reports of the event do not say whether such a lecture occurred.[66]: 46, 52 Later that year, while visiting San Francisco, Nouri was robbed and left at the Napa Insane Asylum, which took him into custody as a patient.[66]: 46 [67] Although he eventually arranged his release, the incident raised questions about his mental state and, therefore, the legitimacy of his extraordinary claims. Upon researching the case for a 2014 paper, Emrah Şahin concluded that "Nouri, though of an unusual character, was sane."[69]: 55–56 An 1897 report that Nouri had been crowned Patriarch at the Chaldean Pontifical Cathedral at Thrissur has been taken as vindication of his authenticity. Nevertheless, Turkish officials did not corroborate his claim of discovering Noah's Ark.[70]

20th century

[edit]Searches since the mid-20th century have been largely supported by evangelical, millenarian churches and sustained by ongoing popular interest, faith-based magazines, lecture tours, videos and occasional television specials.

Alleged Russian expedition

[edit]

In 1940 the article "Noah's Ark Found" appeared in a special edition of New Eden, one of several booklets published in Los Angeles by Floyd M. Gurley. The article was credited to "Vladimir Roskovitsky", and contained his account of discovering Noah's Ark on Mount Ararat circa 1917, "just before the Russian revolution."[62]: 83, 89 [60]: 76–79

According to the story, Roskovitsky was a Russian aviator stationed 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Ararat. In August (no year is provided) he was ordered to perform a test flight of an airplane equipped with a new supercharger. Flying near Ararat, Roskovitsky and his co-pilot spotted an enormous shipwreck on the shore of a lake on the mountain. His captain later identified the wreckage as Noah's Ark, and submitted a report to the government, which sent 150 soldiers to the site. The expedition's report was supposedly sent to the tsar just days before "godless Bolshevism took over," causing the report to be suppressed and presumably destroyed "to discredit all religion and belief in the truth of the Bible." Roskovitsky, identified as a White Russian, is said to have fled to the United States to enjoy the freedom to pursue his newfound faith.[62]: 83–87

The story is inconsistent with Russian history, as Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the throne at the end of the February Revolution, months before the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution.[71]: 31 References to parachutes, oxygen cans, and superchargers in aircraft are anachronistic for the given timeframe.[72] Nevertheless, the story became very popular and was widely reprinted.[73]: 59 [74]: 4 [75] By 1942, however, at least two publications had retracted the story.[73]: 59

Inquiries to New Eden about the article were referred to Benjamin F. Allen, the source for the story.[62]: 87 However, Allen had not intended for the story to be published until it could be corroborated, and he resented the embellishments Gurley had added. In October 1945 he described the version of the story he told to Gurley, writing: "In conversation with him I had given him the few details originating from two soldiers in the Czarist Russian army during the First World War, deceased many years ago. The story by these soldiers came to me from their relatives of how a Russian aviator had sighted a suspicious looking structure in one of Ararat's obscure canyons. Infantrymen were sent on foot to investigate and their officers and they decided it must be Noah's Ark, with one end sunk in a small swamp. These were the only details they gave." Allen said that "95%" of the New Eden article, including the name "Vladimir Roskovitsky", had been fabricated by Gurley, who issued an apology at his request.[62]: 89–91 [60]: 79–82

Despite Gurley's retraction, interest in the Russian aviator story persisted, as attention turned to verifying Allen's version.[76]: 247 [66]: 34–37 [62]: 88–89 [60]: 80–81, 87 Real estate agent Eryl Cummings, who learned of the Roskovitsky story in 1945, was particularly inspired to investigate the possibility that Noah's Ark had been discovered. In November 1945 he founded the Sacred History Research Expedition for the purpose of investigating the matter, and through his research he later came to be considered "the dean of American ark hunters."[66]: 27–30 [76]: 247

Cummings discovered a new lead in an article from the October 6, 1945 issue of the Russian-language magazine Rosseya, which was similar to Gurley's Roskovitsky account. The Rosseya article, written by former Russian officer Alexander A. Koor, placed the tsar's expedition in December 1917, and described the Ark as measuring 500 feet (150 m) long, 83 feet (25 m) wide, and 50 feet (15 m) high. Koor's version ended with a rumor that the expedition's report was intercepted by Leon Trotsky, who had the courier shot.[66]: 55–60 Cummings later contacted Koor, who said he had served in the Ararat region in 1915, and heard of the Ark expedition from fellow officers he met in 1921. This was enough to convince Cummings that Koor had not simply plagiarized the New Eden article.[66]: 61–64 An amateur archaeologist, Koor also claimed to have discovered cuneiform inscriptions at Ararat describing the story of the Flood.[60]: 87 Following his correspondence with Cummings, Koor would take an interest in promoting the discredited Book of Veles.[77]

Aaron J. Smith

[edit]In November 1948, Edwin Greenwald reported for the Associated Press that Kurdish villagers had discovered a large, petrified wooden ship on Mount Ararat.[78][60]: 123 Shukra Asena, who owned land in the area, reported to Greenwald that a farmer named Reshit found the ship's prow in September, about two-thirds of the way up the mountain. Asena claimed that Reshit spread word of his discovery, and people from many of the local villages had climbed Ararat to view the object.[78]

Although the article was largely secondhand hearsay, British amateur archaeologist Egerton Sykes hoped to organize an expedition to establish that Reshit's discovery was in fact Noah's Ark.[79]: 56–57 [66]: 85 Aaron J. Smith, dean of the People's Bible College in North Carolina, joined Sykes in preparing for the operation. The pair received publicity when Pravda accused them of planning a surveillance operation for "Anglo-American imperialists", citing the proximity of Mount Ararat to the Soviet border.[3] When Sykes was unable to proceed due to a lack of funding, Smith went on without him.[66]: 86–87

Upon arrival in Turkey, the expedition spent two months in Istanbul, arranging all of the permits necessary to proceed to Ararat. Following this delay, Greenwald joined Smith's party, which planned to hire Reshit as a guide.[66]: 87–88 However, Reshit could not be located, despite the offer of a reward for information. Although Greenwald's article had indicated that Reshit's find had been witnessed by people throughout the area, no such witnesses could be found by the team.[60]: 118

Although the mission ended in failure, Smith remained hopeful that Noah's Ark would be found on Ararat someday. Expedition member Necati Dolunay argued that the project "has done a great deal for science and research as regards the ark. It finally has utterly disproved opinions and observations during more than 100 years that the ark is in plain sight."[66]: 89–90

In 1986, David Fasold interviewed a man named Ali Oğlu Reșit Sarihan, whom he believed to be the Reshit described by Shukra Asena thirty-eight years earlier. According to Fasold, the object that Reshit allegedly discovered in 1948 was not located on Mount Ararat as originally reported, but was in fact the Durupınar site.[80]: 321–325

Haji Yearam

[edit]Harold Williams, a Seventh-Day Adventist pastor, related the story of Haji Yearam in a 1952 letter to Ark researcher Eryl Cummings.[66]: 111–116 Over the next few years, Eryl and his wife Violet worked to corroborate the story, locating Yearam's death certificate in 1956 and securing Williams's permission, in 1958, to publish his letters.[66]: 119, 123 It is unclear if the story was widely circulated until the 1970s, when Violet Cummings began writing books about the Ark.

Yearam was a devout Seventh-Day Adventist who had immigrated from Armenia to the United States, eventually settling in Oakland, California. In 1915, Harold Williams and his parents began caring for the elderly, ailing Yearam. "Haji asked me to [...] write down carefully a story he was very anxious to tell," Williams wrote, "because he was sure that it would be of use some day after he was dead and gone." According to Williams, this deathbed statement revealed that Yearam, as a boy, had been part of a secret expedition that located Noah's Ark on Mount Ararat.[66]: 112–116 The exact timeframe of this alleged expedition is uncertain, though Violet Cummings concludes that it occurred circa 1856.[66]: 112

In Yearam's story, as related by Williams, his home village was at the foot of Mount Ararat, and his community had once made regular pilgrimages up to the Ark. One day "three vile men who did not believe the Bible" hired Yearam and his father as guides, as they intended to search the mountain in order to disprove the Noah's Ark story. When Yearam's father led them to the Ark, the three scientists "went into a Satanic rage at finding what they hoped to prove nonexistent." After trying and failing to destroy the vessel, the scientists agreed to cover up the discovery and made Yearam and his father swear to keep the secret under threat of torture and murder.[66]: 113–115 Williams later explained that Yearam "wanted his story preserved so that when the right time came it might encourage brave men to go and locate the Ark and give to the world such proof as could not be denied"[66]: 117

Haji Yearam died on 3 May 1920.[66]: 123 Williams claimed that, around that same time, he read a newspaper article about a scientist in London who gave a deathbed confession about concealing the discovery of Noah's Ark. This second account was supposed to be remarkably consistent with the statement Yearam had given. Williams said that he saved the newspaper, keeping it with his transcript of Yearam's story; however, both were destroyed in a 1940 house fire.[66]: 115–116 Despite a diligent search, no copy of the article about the dying scientist has ever been located.[66]: 124–126

The chief criticism of Williams's account is that it is entirely hearsay evidence.[79]: 57–58 Williams is the sole source for a story he considered to be very important in 1920, yet he made no effort to share it before the destruction of his evidence twenty years later, and no effort to publish it until the 1950s.[79]: 49 The motivations of the story's scientists make no sense except to conform to their villainous role in what Larry Eskridge characterizes as a "melodrama".[79]: 50 [76]: 250 The TalkOrigins Archive suggests that the depiction of unbelievers, indicates that the entire story was manufactured as religious propaganda.[81]

Fernand Navarra

[edit]French industrialist Fernand Navarra claimed to have located Noah's Ark in his 1956 book J'ai Trouvé l'Arche de Noé.[82]: 69 According to Navarra, he was inspired to search for the ship in 1937, after listening to an Armenian friend describe the legends his grandfather had told him in 1920.[82]: xiii–xiv In 1952, he was invited to join an Ararat expedition with Jean de Riquer and Sehap Atalay, which reported no sign of the Ark.[82]: 10–11, 30 [83] However, Navarra would later claim that, while alone, he sighted a large, dark mass that he said could only be the Ark. Since he could not reach this object or provide proof for its existence, he decided not to reveal his discovery until he could return.[82]: 36–38

After failing to return to the site in 1953, Navarra resolved to return in 1955. For his next attempt, he sought to avoid potential delays caused by securing permission from the Turkish authorities to climb Ararat. To that end, he disguised the mission as a family vacation, bringing his wife and three sons to Turkey and scaling the mountain with eleven-year-old Raphael Navarra.[82]: 38–41 The father and son filmed their recovery of a 5-foot (1.5 m) beam of hand-hewn wood, which Fernand said was cut from the structure he located in 1952. To make the wood easier to carry without arousing suspicion from the Turks, they cut the beam into smaller pieces.[82]: 63

In 1956 Navarra submitted his wood to several institutions for scientific analysis.[82]: 123–133 The wood was identified as oak. Analyses based on color, density, and lignitization reportedly indicated the wood was about 5,000 years old, in line with the literalist timeframe of the Flood.[84]: 137 However, these methodologies for dating wood are unreliable, and rejected by most scientists.[84]: 139–141 Personal correspondence from 1959 refers to an unknown report that Navarra's wood had been radiocarbon dated to exactly 4,484 years old.[82]: 136 [62]: 135 Such a precise figure is not possible to obtain from radiocarbon dating, and does not correspond to any biblical chronology except that of Navarra, who wrote in 1955 that the Flood occurred "4,484 years ago."[62]: 135

The Archaeological Research Foundation conducted several expeditions to locate Navarra's site in the 1960s, but were unable to find it. Acting as a consultant, Navarra supplied maps which ARF found vague and inconsistent with the mountain.[85]: 317–328 In negotiations for him to personally lead ARF to the site, Navarra demanded considerable financial compensation and royalties from whatever the team might find. The two sides came to an agreement for a 1968 mission, in which Navarra arrived late and injured his foot while attempting to catch up.[62]: 137–141 By 1969 the efforts of ARF had been taken over by a new organization, the SEARCH Foundation, led by Ralph Crawford and with Navarra serving on the board of directors.[85]: 328–329 On a SEARCH expedition in 1969, Navarra became separated from the rest of the party and, shortly thereafter, identified a site where the team found pieces of wood.[85]: 329–332

SEARCH board member Elfred Lee arranged for radiocarbon dating on samples from Navarra's specimens.[62]: 142 The 1955 samples were analyzed by five institutions, with results dating the wood to approximately 1,200-1,700 years ago. Two analyses of the 1969 samples dated the wood to about 1,350 years ago.[86]: 94–101 In 1984, Navarra gave another piece of wood to James Irwin, who submitted it for another round of tests. Irwin's sample was found to be about 1500 years old, with evidence that the pitch coating was of far more recent origin, and applied using modern technology.[87]: 18–21

Several allegations have cast doubt on Navarra's credibility.[60]: 133–134 [4]: 9 Although Navarra said in 1958 that Sehap Atalay had collected wood from the Navarra site, Atalay contradicted that claim in 1962. According to Atalay, Navarra gave him the wood on his way back from the 1955 expedition.[85]: 317–318 In 1970, Jean de Riquer accused Navarra of attempting to buy ancient wood from villagers at the foot of Ararat during their 1952 expedition.[62]: 161 [85]: 331 During his own ascents of Ararat, Gunnar Smars met Kurdish guides who accompanied Navarra on one or more private climbs around 1968 or 1969, unbeknownst to SEARCH.[85]: 331

Durupınar site

[edit]

During a 1959 geodetic survey of Turkey, an anomalous shape near Doğubayazıt was identified by İlhan Durupınar of the Turkish Air Force and Sevket Kurtis of Ohio State University.[66]: 127–128 [88]: 112, 114 [89] The size and shape of the object resemble a boat approximately 450 feet (140 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide, inviting speculation that it could be Noah's Ark.[66]: 128–130 Evangelist George Vandeman organized an expedition to the site in 1960, which determined that the shape was a natural geological formation.[66]: 133–135

Interest in the site was renewed by Ron Wyatt, who visited the site in 1977, 1979, and 1984.[90]: 275 Based on Wyatt's promotion of his research, the Turkish government declared the site a national park in 1986.[90]: 278–279 Geophysicist John Baumgardner and salvage expert David Fasold strongly advocated that the site was in fact Noah's Ark, but both of them eventually broke with Wyatt to express misgivings about their findings.[90]: 282–284, 291–293 In 1996, Fasold co-authored a paper with geologist Lorence G. Collins, asserting that the site "cannot have been Noah's Ark nor even a man-made model."[89]

George Greene

[edit]In the mid-1960s, oil engineer Fred Drake claimed to have seen six photographs of Noah's Ark in 1954. According to Drake, the photos were taken by his colleague George Greene, who had taken a helicopter flight around Mount Ararat while working at a Turkish oil pipeline. The pictures showed an unidentified protrusion on the mountain, resembling the prow of a large wooden ship. An investigation by the Archeological Research Foundation determined that Greene tried and failed to organize an expedition to Ararat, and then relocated to British Guiana, where he died in 1962. Greene's friends and family were uncertain what became of his Ararat photos, which were never found.[66]: 138–144

A 1990 article by Bill Crouse listed various natural formations on Ararat that appeared to resemble a ship in photographs until mountaineers examined them in person. Crouse believed one of these "phantom arks", a prow-shaped chunk of basalt photographed by Tom Crotser in the 1970s, could be the same object seen by Greene.[91]

Georgie Hagopian

[edit]In 1970, Armenian-American Georgie Hagopian reported that his uncle took him to see Noah's Ark twice during his childhood. Different accounts of his story place the first sighting in 1902, 1906, or 1908, with the second incident occurring about two years later.[60]: 69 [25]: 113–118 [66]: 186–190 [92] According to this account, the moss-covered Ark lay on the edge of a cliff, so that only one side was accessible.[25]: 114, 116 Hagopian said that many other boys in his childhood community told him that they had seen the structure.[66]: 190 The TalkOrigins Archive takes issue with the "apparent ease" with which these children supposedly reached the Ark site, in contrast with the difficulties reported by other explorers.[93]

By Hagopian's estimate, the Ark was over 1,000 feet (300 m) long, 600–700 feet (180–210 m) wide, and over 35 feet (11 m) high. To reconcile this estimate with traditional interpretations of the Ark's size, John Warwick Montgomery suggested that "Dimensions regularly appear greater than they actually are to small children."[25]: 114 However, Hagopian's recollection of an 18-inch (46 cm) window (which is consistent with traditional views) is accepted as a precise estimate by Violet Cummings.[66]: 191–192

Hagopian said that his uncle wanted to keep a piece of the Ark, but was unable to cut into the wood using a knife or a blast of gunpowder. He adamantly rejected Fernand Navarra's claim to have found fragments of the Ark.[66]: 189–190 Attempting to reconcile the two claims, Montgomery raised the possibility that the Ark was "not uniformly petrified."[25]: 113 Hagopian, however, believed the entire structure was "absolutely petrified," and that "Almighty God would never permit the Ark to be cut and broken up."[66]: 190

James Irwin

[edit]

Astronaut James Irwin, the eighth person to walk on the Moon, experienced a religious epiphany during the Apollo 15 mission in 1971. The following year, he resigned from NASA and founded an evangelical organization, the High Flight Foundation.[94][95] During his outreach work, Irwin met Eryl Cummings in 1976 and expressed interest in joining one of his expeditions in search of Noah's Ark.[96]: 7 At the time, Turkish policy had closed off Mount Ararat to explorers, and Irwin was denied a permit in 1977. However, following the 1980 coup Irwin's celebrity allowed him to establish a rapport with President Kenan Evren, who invited him to lead an expedition in 1982.[96]: 7, 14 [97]

Irwin's 1982 mission ended in disaster when he left the group, in search of a shortcut to the summit, and fell off the trail. He had no memory of what caused the fall, but later speculated that he'd been caught in a rockslide and struck by a rock. He awoke hours later, badly wounded, and crawled into his sleeping bag to survive the night.[96]: 63–64 The expedition team sent out a search party the following day, which rescued him and brought him down the mountain for medical treatment.[96]: 70–86 [98]

Undeterred, Irwin returned to Ararat a month later, this time with his wife and son.[97][87][page needed] He hoped to pursue a tip offered to him by another explorer, who reported seeing an object about 12,000 feet (3,700 m) up the mountain in Ahora Gorge. Mary Irwin later expressed misgivings about her husband's mental state so soon after his fall. "Because Jim’s rationale wasn’t quite right after being hit so hard on his head," she wrote in 2012, "he deduced we wouldn’t need backpacks and climbing gear." Without proper equipment, the team struggled to make progress during the night, and were forced to abandon the expedition.[87][page needed]

In August 1983, Irwin made another attempt, partnering with Marvin Steffins.[99][100] They chartered an airplane to survey Ararat, and led a 22-member expedition, including Eryl Cummings and several members of Irwin's family.[87][page needed][100] During the climb, a Turkish guide had sighted wood where the snowline had receded.[100] A blizzard forced the team to turn back before they could reach the site.[101]: 14 "It's easier to walk on the moon," Irwin said, regarding the difficulties in climbing Ararat. "I've done all I possibly can, but the ark continues to elude us."[100]

Irwin fully intended to try again in 1984. However, he acknowledged the possibility that the Ark might not be found. Although he firmly believed the ship had really existed, he was far less certain that it had not been destroyed over the centuries. "The likelihood of it surviving at all," he said, "is small." He also suspected that many of the reported sightings on Mount Ararat were false.[97] Nevertheless, he scaled the mountain that summer to look for the wood sighted the previous year. When he reached the site, he found only a pair of abandoned skis.[101]: 14 [102]: 244

During the 1985 climbing season, Kurdish rebels had ambushed at least four parties on Ararat.[103] By the time Irwin could begin his climb on 24 August, only five of his 22-member party were allowed to accompany him, and the expedition was escorted by thirty Turkish soldiers.[104] Just as the team reached the summit, Turkish officials ordered them to descend. By the time the party received permission to resume the mission, they were too exhausted to continue. According to the US Ambassador to Turkey, Robert Strausz-Hupé, the government was reacting to Soviet maneuvers near the border, and concern that Irwin would become a high value target for terrorists.[105]: 235–240

Irwin planned to make a sixth trip to Ararat in July 1986, with a smaller team.[106] These plans were disrupted when he suffered arrhythmia on 6 June.[107] By July, however, he had resumed plans for the expedition.[108] "My doctor is against my traveling, and he said that I cannot go over 10,000 feet," Irwin said. "But the Lord willing, I will be there."[109] After completing an aerial survey of Ararat, Irwin's team was detained at their hotel, under accusations of violating Soviet and Iranian airspace. The party was released once local officials confirmed Irwin's flight had been authorized.[110][111]: 35–37 According to expedition member Bob Cornuke, Irwin expressed concern that his fame attracted media attention and security risks that were hampering the search. "Jim himself had confided on our last trip, as the permit process reached new heights of lunacy, that the problems could be traced to him, not (as some had come to suspect) a sinister Turkish plot to prevent us from finding the ark."[111]: 27–29 In September, Irwin announced "I think I’ve done all I can to attract attention to the ark. I think it is time others take up the search."[112]

A 1987 heat wave in Turkey convinced Irwin to change his mind and return for his seventh expedition to Mount Ararat. He believed the warm temperatures might have melted enough of the mountain's glaciers to make Noah's Ark easier to spot from the air.[113][114] Irwin's High Flight Foundation teamed with the Institute for Creation Research, Evangelische Omroep, and International Exploration, Inc. for a joint operation. According to ICR's John D. Morris, the Turkish government had banned exploration of Ararat earlier in the year, and only approved this expedition on the condition that the team also evaluate the Durupınar site. Permits to explore Ararat itself were revoked before the party could begin its intended mission. Ultimately the expedition was only able to arrange a high-altitude aerial survey, staying no less than 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Soviet and Iranian airspace.[115]

The 1987 expedition would be Irwin's last, as doctors ordered him to give up the search.[116] When the High Flight Foundation organized another trip in 1988, Bob Cornuke led the party while Irwin stayed home.[111]: 18–24

Ed Davis

[edit]

Optometrist and Ararat explorer Don Shockey learned in 1985 that Ed Davis had spoken to his church about seeing Noah's Ark during World War II.[117] Shockey invited Davis to speak at an "ark-a-thon" convention he organized in 1986 at Farmington, New Mexico.[111]: 15–16 Davis was interviewed extensively about his story by Shockey's FIBER organization, and later subjected to a polygraph test on behalf of James Irwin's High Flight Foundation.[118][119][111]: 17–22

In 1943 Davis was a sergeant in the United States Army Corps of Engineers, stationed in Hamadan to work on the Persian Corridor between Khorramshahr and Qazvin.[118]: 4, 44 [120]: 308 According to Davis, during this assignment he befriended a local driver named Badi, and his father Abas-Abas, who claimed to have visited Noah's Ark atop the mountain near their village. Around 1 July, Abas-Abas invited Davis to join them in one such visit, saying that enough snow and ice had melted to partially expose the ship. Upon reaching "Doomsday Point", Davis said he saw the Ark, which "first appeared as a huge rock formation covered by fog." It was lying in a cove lake, within a canyon below his position, and broken into two portions. Abas-Abas claimed that the Ark had been whole in his youth, and had only broken apart within his lifetime.[118]: 4–8

Ark researchers disagree about whether Davis's experience involved Mount Ararat in Turkey's Ağrı Province. Davis said the mountain he visited could be seen from his unit's base in Hamadan, but Ağrı is 400 miles (640 km) away.[121] The first published version of his account describes Badi and Abas-Abas as Kurds, which is consistent with a story about visiting a village in Ağrı.[118]: 4–7 However, in footage of his original interview Davis says the villagers were Lurs, an ethnic group in western Iran.[111]: 56 [121] Several different mountains in Lorestan are identified by the Lurs as the landing site of Noah's Ark.[122]: 100 [111]: 89–93, 154 Similarly, Lur tradition places the Garden of Eden, which Davis also reported seeing, in Lorestan.[123]: 3

George Jammal hoax

[edit]In November 1985, actor George Jammal wrote to Duane Gish, vice-president of the Institute for Creation Research, falsely claiming to have searched for Noah's Ark between 1972 and 1984. Jammal described being aided by "Mr. Asholian", "Alis Buls Hitian", and "Vladimir Sobitchsky". The story culminated with Jammal and Vladimir locating the Ark in a cave of ice, whereupon Vladimir fell to his death trying to photograph the ship. Jammal also claimed to have taken a piece of wood from the site.[124]

ICR's John D. Morris responded to Jammal in 1986, seeking to arrange an interview. Jammal prepared by studying books about the search for the Ark, as well as the 1976 Sun Classic Pictures film In Search of Noah's Ark. During the interview, Jammal used cold reading techniques to elicit information from Morris that would determine Jammal's answers to Morris's questions.[124] According to Jammal, Morris repeatedly offered to finance an expedition to corroborate his story.[125]

Years later, when Sun began work on a follow-up to In Search of Noah's Ark, Morris shared his information on Jammal. David Balsiger, researching the story for Sun, was advised by Ark researchers David Fasold and Bill Crouse that Jammal's account was not credible. Unsure whether to perpetuate the hoax, Jammal contacted noted skeptic Gerald A. Larue, who described how he felt misrepresented by Sun's 1992 TV-movie Ancient Secrets of the Bible.[124][125] On 20 February 1993, CBS aired Sun's The Incredible Discovery of Noah's Ark, which featured a segment on Jammal's story and showed him displaying a piece of wood purportedly taken from the Ark.[126][124] Larue issued a press release exposing the hoax, which was largely ignored until Time covered the story in July.[124]

Following the exposure of the hoax, Jammal was initially reluctant to comment for fear of legal reprisal.[124] However, in October 1993 he admitted that he made up the entire story.[127] The wood he presented on-screen had in fact been pine found near some railroad tracks in Long Beach, California, which he boiled with spices and baked in an oven.[127][125] Jammal was critical of Sun's failure to verify his story. "I even gave the production company a piece of the wood to test," he wrote, "but they obviously weren't interested in truth; all they wanted was a good performance. If they had actually been concerned about truth, they should have asked me why Noah's Ark smelled like teriyaki sauce!"[125] A representative for Sun stated that Jammal's segment would be edited from future releases of The Incredible Discovery of Noah's Ark.[127]

21st century

[edit]Daniel McGivern

[edit]Honolulu businessman Daniel McGivern began investigating the search for Noah's Ark in 1995, and eventually financed commercial satellite photos of Mount Ararat.[128] According to his research, a 2003 heat wave melted enough ice and snow on the northwestern slope to reveal a dark patch, which he interpreted as resembling three beams and a crossbeam.[129] In April 2004, McGivern and Turkish mountaineer Ahmet Ali Arslan announced plans for an expedition to the site in July.[128][130][131] A Guardian article associated McGivern's site with the Ararat anomaly, a similar phenomenon observed in surveillance photos of Mount Ararat declassified by the US government in the 1990s.[132]

Although McGivern hoped to begin the expedition by 15 July, he instead spent the entire summer trying to obtain approval from the Turkish government. His request was finally declined in September.[133] Critics suggested that McGivern announced the expedition before obtaining permission as a publicity stunt to persuade Turkey to authorize it. The choice of Arslan, who claimed in 1989 to have photographed Noah's Ark, to lead the mission was also questioned. "Ahmet is a big talker," according to an ark researcher commenting to National Geographic. "In one conversation he will say that he has 3,000 photos, and in another conversation ten minutes later 5,000 photos."[130]

McGivern said he would not make another attempt the following year. "I don't have Ark fever like many who go year after year," he said. "A good businessman calculates what amount of money and time he will invest and has to know when to walk away."[133] However, in 2011 he said he had funded other, smaller expeditions, and had spent $500,000 on research.[134]

Bob Cornuke

[edit]

During an unsuccessful expedition in 1988, Bob Cornuke became convinced that Noah's Ark could not be on Mount Ararat.[111]: color plate 6 He gave up the search, forming the Bible Archeology Search and Exploration Institute in 1992 to seek out other biblical locations and artifacts. However, in 1998 Cornuke learned of the idea that Genesis 11:2 places the Ark's landing site east of Shinar.[111]: 45–47 In this context he reevaluated the testimony of Ed Davis, and concluded that the site Davis described must be in Iran.[111]: 51–57, 63

In June 2006, the BASE Institute announced the discovery of a large object resembling petrified wood on Mount Takht-e Suleyman in the Alborz.[135][136][137] The object, located 13,000 feet (4,000 m) above sea level, was reported to be similar in size to estimates for the Ark.[136] The BASE website asserted that this object was the same one Ed Davis claimed to have seen, but stopped short of proclaiming it Noah's Ark, instead calling it "a candidate."[138] "I think we've found something that deserves a lot more research," Cornuke said. "It has a distinct possibility that it could be something like the ark."[139]

Critics of the announcement objected to the lack of peer review on Cornuke's findings.[7][140] Looking at the expedition's photos, experts in geology and ancient timber disputed the possibility that the object was petrified wood.[137] The expedition included many "business, law, and ministry leaders," but no professional geologists or archaeologists.[141] Cornuke's interpretation of scripture was also criticized, as Genesis does not indicate whether Noah's descendants migrated to Shinar directly from Ararat, or from some unnamed intermediate location.[142] Moreover, Genesis 11:2 can be plausibly translated to indicate that the clan migrated eastward, suggesting a point of origin west of Shinar.[123]: 6–7

By 2010, Cornuke had stopped looking for Noah's Ark, saying "I came down (from the mountain) with all this evidence for Noah’s Ark, and nobody cared."[143] In 2012 he wrote "In all my 25 years of searching for the ark I have never seen the old boat."[144]: xi

Noah's Ark Ministries International

[edit]

In 2004, Media Evangelism founder Andrew Yuen Man-fai and pastor Boaz Li Chi-kwong announced the discovery of parts of Noah's Ark on Mount Ararat. They reported that their team found a large wooden structure at an elevation of 4,200 metres (13,800 ft) during their fourth trip to the mountain.[145] According to an exhibit at Hong Kong's Noah's Ark theme park, the search team had been exploring Ararat as Noah's Ark Ministries International (NAMI) since 2003.[146] Yuen and Li had no evidence of their claim beyond blurred images, as they said a "mysterious force" disrupted their video footage.[145] In 2005, Media Evangelism released a documentary, The Days of Noah, based on the NAMI expedition.[147]

According to NAMI's website, Turkish mountaineer Ahmet Ertuğrul (nicknamed "Paraşut") submitted a sample of petrified wood to NAMI, which he claimed to have obtained in August 2006 from a second wooden structure, located 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) up Mount Ararat. NAMI claimed that an expedition was sent in February 2007, which found that the 2004 site had collapsed due to an earthquake, and was prevented from examining the 2006 site due to weather conditions.[148] An October 2007 press conference announced that a follow-up mission in August successfully recovered more petrified wood from the site Ertuğrul reported.[148][149]

In a press conference on 25 April 2010, NAMI announced that an October 2009 expedition had excavated and filmed the wood structure discovered by Ertuğrul.[150][151][152][153] Although NAMI's website claimed Ertuğrul discovered the site in August 2006, he stated at the press conference that he learned of it in June 2008.[148][153] The wooden structure reported by Yuen and Li in 2004 was not addressed.[153] According to NAMI, specimens from the site were carbon-dated to 4800 BP.[152][154] Footage of the interior of the structure was released on NAMI's YouTube account.[155] NAMI said that Turkey would submit the location for designation as a World Heritage Site; however, when reached for comment a spokesperson for UNESCO said that the organization had not received such a request.[151]

The immediate response to the announcement was largely skeptical.[156][157] Mainstream scientists objected to the lack of professional archaeologists involved with the research, and the decision to reveal the findings via a media event rather than publishing a peer-reviewed study.[150][158] Creationists also expressed concern about the lack of data available for independent corroboration.[159] Andrew A. Snelling later said that NAMI supplied him with their radiocarbon dating report, which showed that only one test of one sample had produced the publicized result of 4800 BP. Moreover, Snelling rejected the 4800 BP result as evidence for Noah's Ark, based on creationist beliefs about carbon-14 levels in antediluvian wood.[160] Turkey's Ministry of Culture and Tourism expressed doubt that NAMI secured permission to conduct their expeditions, and began an investigation as to how NAMI transported its wood samples from Turkey to China.[161][162]

Within days of the announcement, Randall Price, who had consulted with NAMI in 2008, came forward with allegations that Ertuğrul hired Kurdish workers to construct the site using wood from an old structure near the Black Sea.[163][164][165][166] NAMI issued a statement saying that its relationship with Price ended in October 2008, and he was therefore unfamiliar with findings made after that time.[167] Defending NAMI's claims, team members argued that it would not be possible to haul enough materials up Mount Ararat to build the structure that they had described.[161] In rebuttal, Price and his colleague Don Patton cited the use of heavy equipment in other Ararat expeditions, as well as a 2007 publicity stunt in which Greenpeace built a 10-metre (33 ft) replica of Noah's Ark on the mountain.[168]: 27–28 [169]

After promoting the release of the 2011 film The Days of Noah 2: Apocalypse, the NAMI website NoahsArkSearch.net was no longer updated.[170][171] Support for NAMI's claims was later taken up by Norman Geisler, who invited Ertuğrul to speak at an apologetics conference organized by Southern Evangelical Seminary in October 2015.[171][172][173][174] Joel Klenck, formerly associated with NAMI, has continued to promote NAMI's claims as recently as December 2020.[175]

NAMI and Ertuğrul never disclosed the location of the site they reported, although Price and Patton claimed in 2010 to have independently located it.[175][168]: 18–19 Donald Mackenzie, a self-styled missionary who had searched for Noah's Ark for nearly a decade, traveled to Ararat in 2010 hoping to find Ertuğrul's site on his own. Mackenzie contacted his family from the mountain in September, but was never heard from again. His abandoned campsite was later found, but the circumstances of his disappearance remain unknown.[176][177]

Conflicting opinions

[edit]Modern organized searches for the ark tend to originate in American evangelical circles. According to Larry Eskridge,

An interesting phenomenon that has arisen within twentieth-century conservative American evangelism – the widespread conviction that the ancient Ark of Noah is embedded in ice high atop Mount Ararat, waiting to be found. It is a story that has combined earnest faith with the lure of adventure, questionable evidence with startling claims. The hunt for the ark, like evangelism itself, is a complex blend of the rational and the supernatural, the modern and the premodern. While it acknowledges a debt to pure faith in a literal reading of the Scriptures and centuries of legend, the conviction that the Ark literally lies on Ararat is a recent one, backed by a largely twentieth-century canon of evidence that includes stories of shadowy eyewitnesses, tales of mysterious missing photographs, rumors of atheistic conspiracy, and pieces of questionable "ark wood" from the mountain. (...) Moreover, it skirts the domain of pop pseudoscience and the paranormal, making the attempt to find the ark the evangelical equivalent of the search for Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster. In all these ways, it reveals much about evangelicals' distrust of mainstream science and the motivations and modus operandi of the scientific elite.[76]: 245

Ark-seeker Richard Carl Bright considers the search for the ark a religious quest, dependent on God's blessing for its success. Bright is also confident that there is a multinational government conspiracy to hide the "truth" about the ark:

I firmly believe that the governments of Turkey, Russia, and the United States know exactly where the ark sits. They suppress the information, but (...) God is in charge. The structure will be revealed in its time. We climb the mountain and search, hoping it is, in fact, God's time as we climb. Use us, O Lord, is our prayer.[102]: 78

See also

[edit]- Archaeological forgery

- Biblical archeology

- Biblical literalism

- Creationism

- Flood myth

- Flood geology

- In Search of Noah's Ark

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

References

[edit]- ^ a b Josephus, Titus Flavius (1961) [circa 93-94 CE]. Jewish Antiquities, Books I-IV. Josephus. Vol. IV. Translated by Thackeray, H. St. J. London: William Heinemann. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ a b Faustus of Byzantium (1985). "Concerning Yakob (James) of Mcbin (Nisibis).". P'awstos Buzand's History of the Armenians. Translated by Bedrosian, Robert. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Russia: Suspicion On The Mount". Time. 25 April 1949. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Moore, Robert A. (Fall 1981). "Arkeology: A New Science in Support of Creation?" (PDF). Creation/Evolution. Vol. 2, no. 4 VI. pp. 6–15. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Montgomery, John Warwick (7 January 1972). "Arkeology 1971". Christianity Today. Vol. XVI, no. 7. pp. 50–51. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Brian (September 2020). "Did Someone Really Find Noah's Ark?". Acts & Facts. Vol. 49, no. 9. Dallas: Institute for Creation Research. p. 20. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ a b Cline, Eric H. (30 September 2007). "Raiders of the faux ark". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth L. (1996). "Pseudo-Archaeology". In Fagan, Brian M.; Beck, Charlotte; Michaels, George; Scarre, Chris; Silberman, Neil Asher (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195076184. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2009). Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199741076. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth L. (2010). Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 196. ISBN 978-0313379192. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Genesis 8:3–4

- ^ "Book of Jubilees 7:1". Sefaria. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Shurpin, Yehuda (27 October 2019). "What Happened to Noah's Ark?". Chabad.org. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Talmud, b. Sanhedrin 96a

- ^ 2 Kings 19:37

- ^ Esther 5:14

- ^ a b Conybeare, F. C. (April 1901). "Untitled review of Ararat und Masis. Studien zur armenischen Altertumskunde und Litteratur by Friedrich Murad". The American Journal of Theology. 5 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 335–337. doi:10.1086/477703. JSTOR 3152410.

- ^ "Targum Onkelos Genesis 8:4". Sefaria. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Targum Jonathan Genesis 8:4". Sefaria. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (July–September 1964). "The Jews in Pagan Armenia". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 84 (3). American Oriental Society: 230–240. doi:10.2307/596556. JSTOR 596556.

- ^ Büchler, Adolf (January 1897). "The Sources of Josephus for the History of Syria (In "Antiquities", XII, 3-XIII, 14)". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 9 (2). University of Pennsylvania: 311–349. doi:10.2307/1450594. JSTOR 1450594.

- ^ Josephus, Titus Flavius. Complete works of Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews; The wars of the Jews against Apion, etc., etc. Vol. III. New York: Bigelow, Brown & Co. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Genesis 8:4 (Latin Vulgate)". LatinVulgate.Com. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Epiphanius of Salamis (2009). Thomassen, Einar; van Oort, Johannes (eds.). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis Book I (Sects 1-46). Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies. Vol. 63. Translated by Williams, Frank. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 9789004170179. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Montgomery, John Warwick (1974) [1972]. The Quest for Noah's Ark (2 ed.). Minneapolis: Dimension Books. ISBN 0871234777. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Petrosyan, Hamlet (2001). "The Sacred Mountain". In Abrahamian, Levon; Sweezy, Nancy (eds.). Armenian Folk Arts, Culture, and Identity. Bloomington: Indiana University. pp. 33–39. ISBN 0253337046. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Isidore of Seville (2006) [c. 615-636]. The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (PDF). Translated by Barney, Stepehen A.; Lewis, W. J.; Beach, J. A.; Berghof, Oliver. With the collaboration of Muriel Hall. Cambridge: Cambridge University. ISBN 9780511217593. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Quran 11:44 (Translated by Pickthall)

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said (October–December 2004). "A Reflection on Two Qurʾānic Words (Iblīs and Jūdī), with Attention to the Theories of A. Mingana". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 124 (4). American Oriental Society: 675–689. doi:10.2307/4132112. JSTOR 4132112.

- ^ Theophilus of Edessa (2011) [8th c.]. Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Translated Texts for Historians. Vol. 57. Translated by Hoyland, Robert G. Liverpool: Liverpool University. ISBN 978-1-84631-697-5. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Benjamin of Tudela (1928) [12th c.]. "The Travels of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela". In Komroff, Manuel (ed.). Contemporaries of Marco Polo. New York: Liveright. pp. 251–322. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ William of Rubruck (1928) [13th c.]. "The Journal of Friar William of Rubruck". In Komroff, Manuel (ed.). Contemporaries of Marco Polo. New York: Liveright. pp. 51–209. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Odoric of Pordenone (1928) [14th c.]. "The Journal of Friar Odoric". In Komroff, Manuel (ed.). Contemporaries of Marco Polo. New York: Liveright. pp. 211–250. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Mandeville, John (1905) [14th c.]. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. London: Macmillan and Co. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Polo, Marco (1926) [13th c.]. Komroff, Manuel (ed.). The Travels of Marco Polo. Translated by Marsden, William. New York: Liveright. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ a b Hayton of Corycus (2004) [1307]. "The Kingdom of Armenia". Het'um the Historian's History of the Tartars [The Flower of Histories of the East]. Translated by Bedrosian, Robert. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Olearius, Adam (1662). The Voyages & Travels of the Ambassadors from the Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia. Translated by Davies, John. London: Thomas Dring and John Starkey. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Petachiah of Regensburg (1856) [ca. 1187]. Travels of Rabbi Petachiah, of Ratisbon. Translated by Benisch, A. London: Trubner & Co. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Raleigh, Walter (1829) [1614]. "That the ark rested upon part of the hill Taurus, or Caucasus, between the East Indies and Scythia.". The History of the World, Book I. The Works of Sir Walter Raleigh, Kt. Vol. II. Oxford: Oxford University. pp. 217–247. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ a b Parrot, Friedrich (1859) [1834]. Journey to Ararat. Translated by Cooley, W. D. New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ a b Bryce, James (1896) [1877]. Transcaucasia and Ararat: Being Notes of a Vacation Tour in the Autumn of 1876 (4th ed., revised ed.). London: MacMillan and Co. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Buried by Snow Avalanches". The Sun. New York. 26 March 1883. p. 1. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Dreadful Loss of Life". Indianapolis Journal. 26 March 1883. p. 2. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Over a Hundred Persons Killed by Snow Avalanches". Portland Daily Press. Portland, Maine. 26 March 1883. p. 1. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Destructive Avalanches at Mount Ararat". New Zealand Herald. Vol. XX, no. 6664. Auckland. 28 March 1883. p. 5.

- ^ a b Reed, George McCullagh (31 March 1883). "Calamo Currente". New Zealand Herald. Vol. XX, no. 6667. Auckland. p. 1 (supplement). Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Rudman, Brian (1 April 2004). "NZ hoax went round world". New Zealand Herald. Auckland. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Benbow, Hannah-Lee (2009). "I Like New Zealand Best": London Correspondents for New Zealand Newspapers, 1884-1942 (Master of Arts in History). University of Canterbury. doi:10.26021/5181. hdl:10092/3047. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Çağlar, Burhan (March 2017). Brief History of an English-language Journal in the Ottoman Empire: The Levant Herald and Constantinople Messenger (1859-1878) (M.A. thesis). University of Toronto. hdl:1807/76645. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Reed, George McCullagh (24 November 1883). "Calamo Currente". New Zealand Herald. Vol. XX, no. 6871. Auckland. p. 9 (supplement). Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Noah's Ark found". Ashburton Guardian. Vol. IV, no. 942. 14 May 1883. p. 2. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Reported Discovery of Noah's Ark". Australian Town and Country Journal. Sydney. 23 June 1883. p. 27. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "The Latest Ark-aeological Find". The Weekly Mail. Henry Mackenzie Thomas. 28 July 1883. hdl:10107/3372750. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Noah's Ark: Discovered on Mount Ararat". Chicago Daily Tribune. 10 August 1883. p. 5.

- ^ "The Ark Found". Daily Globe. St. Paul, Minnesota. 11 August 1883. p. 1. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Noah's Ark Discovered". The Silver State. Unionville, Nevada. 21 August 1883. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "[untitled]". The Straits Times. Vol. XXIV, no. 15089. Singapore. 25 August 1883. p. 2. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Reported Discovery of Noah's Ark". Saints' Herald. Vol. 30, no. 36 (539). Lamoni, Iowa. 8 September 1883. p. 570. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Aalten, Gerrit (11 February 2020). "1883 Noah's Ark Discovery Hoax". Ark InSight. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i LaHaye, Tim F.; Morris, John D. (1976). The Ark on Ararat. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 0840751109. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Berlitz, Charles (1987). The Lost Ship of Noah: In Search of the Ark at Ararat. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 25. ISBN 0-399-13182-5. OL 2731060M. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Noorbergen, Rene (1974). The Ark File. Mountain View, California: Pacific Press. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Castellano, Michael. "News from Constantinople". www.arkonararat.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Nissen, Henri (26 January 2015). Clark, Anne (ed.). Noah's Ark - Ancient Accounts and New Discoveries. Translated by Skondin, Tracy Jay; Steuer, Bruce; Orbesen, Dorthe; Kjaedegaard, Irene. Copenhagen: Scandinavia Publishing House. ISBN 9788771321111. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Coan, Frederick G. (1939). Yesterdays in Persia and Kurdistan. Claremont, California: Saunders Studio Press. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Cummings, Violet M. (1973). Noah's Ark: Fable or Fact?. San Diego: Creation-Science Research Center. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b "The Chaldean Patriarch: The Prince of Nouri Kidnaped at San Francisco". Indianapolis News. Vol. XXV, no. 61 (7, 537). 15 February 1894. p. 5. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Barrows, John Henry (1899). Barrows, Mary Eleanor (ed.). A World-Pilgrimage (3 ed.). Chicago: A. C. McClurg. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Şahin, Emrah (2014). "Sultan's America: Lessons from Ottoman Encounters with the United States" (PDF). Journal of American Studies of Turkey. 39: 55–76. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "John Joseph Nouri Crowned". San Francisco Call. Vol. 81, no. 140. 19 April 1897. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Zindler, Frank R. (August 1986). "Stalking the Elusive Mountain Boat: The Quest for Noah's Ark". American Atheist. Vol. 28, no. 8. pp. 28–31. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Wood, Lynn H. (18 July 1946). "Has Noah's Ark Been Found?" (PDF). Present Truth. Vol. 62, no. 15. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ a b Bright, John (December 1942). "Has Archaeology Found Evidence of the Flood?". The Biblical Archaeologist. 5 (4). University of Chicago: 55–62, 72. doi:10.2307/3209284. JSTOR 3209284. S2CID 134227592.

- ^ "Has Noah's Ark Been Discovered?" (PDF). The Baptist Examiner. Vol. 11, no. 39 (247). Russel, Kentucky. 14 November 1942. pp. 1–2, 4. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Hoehn, Herman. "Have Any Remains Of Noah's Ark Ever Been Found?" (PDF). Hoehn Research Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021. Alt URL

- ^ a b c d Eskridge, Larry (1999). "A Sign for an Unbelieving Age: Evangelicals and the Search for Noah's Ark". In Livingstone, David N.; Hart, D. G.; Noll, Mark A. (eds.). Evangelicals and Science in Historical Perspective. Oxford UP. pp. 244–263. ISBN 9780195353969.

- ^ Ilieva, Polina. "Register of the Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Kurenkov (A. A. Koor) Papers". Online Archive of California. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Edwin (13 November 1948). "Petrified Ship Parts on Ararat". Townsville Bulletin. Townsville, Queensland. p. 3. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bailey, Lloyd R. (1978). Where is Noah's Ark?. Nashville: Abingdon. ISBN 0687450934. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Fasold, David (1988). The Ark of Noah. New York: Wynwood Press. ISBN 9780922066100. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Isaak, Mark, ed. (7 May 2003). "CH505.1: Yeararm and the ark". An Index to Creationist Claims. TalkOrigins Archive. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "French Expedition to Mt. Ararat Fails to Find Traces of Noah's Ark". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 18 August 1952. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b Bailey, Lloyd R. (December 1977). "Wood from "Mount Ararat": Noah's Ark?". The Biblical Archaeologist. 40 (4). University of Chicago: 137–146. doi:10.2307/3209528. JSTOR 3209528. S2CID 135050048.

- ^ a b c d e f Cummings, Violet M. (1982). Has Anybody Really Seen Noah's Ark?. with Phyllis E. Watson. San Diego: Creation-Life Publishers. ISBN 0890510865.

- ^ Bailey, Lloyd R. (1989). Noah: The Person and the Story in History and Tradition. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina. ISBN 0872496376. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Irwin, Mary (24 October 2012). The Unsolved Mystery of Noah's Ark. Bloomington, Indiana: WestBow Press. ISBN 9781449764777. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Noah's Ark? Boatlike form is seen near Ararat". Life. Vol. 49, no. 10. 5 September 1960. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ a b Collins, Lorence Gene; Fasold, David Franklin (1996). "Bogus "Noah's Ark" from Turkey Exposed as a Common Geologic Structure". Journal of Geoscience Education. 44 (4): 439–444. Bibcode:1996JGeEd..44..439C. doi:10.5408/1089-9995-44.4.439. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Sellier, Charles E.; Balsiger, David W. (April 1995). The Incredible Discovery of Noah's Ark. New York: Dell. ISBN 0440217997. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Crouse, Bill (February–March 1990). "Phantom Arks On Ararat" (PDF). The Ararat Report. No. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Stack, Robert (host) (26 February 1992). "Episode #4.22". Unsolved Mysteries. Season 4. Episode 22. 5:33 minutes in. NBC. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Isaak, Mark, ed. (7 May 2003). "CH505.4: Hagopian and the Ark". An Index to Creationist Claims. TalkOrigins Archive. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "James Irwin dead at 61 - astronaut and evangelist". Chicago Sun-Times. 10 August 1991.

- ^ "Ex-Astronaut James Irwin, 61; Founded Evangelical Organization". Chicago Tribune. 11 August 1991. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Irwin, James B. (1985). More than an Ark on Ararat: Spiritual lessons learned while searching for Noah's ark. With Monte Unger. Nashville: Broadman Press. ISBN 0805450181. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Hacker, Kathy (31 January 1984). "Ex-Astronaut blasts off on new mission: Find Noah's Ark". Tempo. Chicago Tribune. p. NW1-2.

- ^ Rizvi, Sajid (21 August 1982). "[untitled]". UPI. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Ex-astronaut vows to persist in search for biblical ark". Chicago Tribune. 17 August 1983. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Howe, Marvin (1 October 1983). "The rush is on to climb Mt Ararat". The Canberra Times. p. 11. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b Toumey, Christopher P. (October 1997). "Who's Seen Noah's Ark?". Natural History. Vol. 106, no. 9. pp. 14–17. hdl:2246/6503. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b Bright, Richard Carl (2001). Quest for Discovery: One Man's Epic Search for Noah's Ark. Green Forest, Arkansas: New Leaf. ISBN 0892215054. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Goltz, Thomas C. (25 August 1985). "Raiders search for Noah's Ark". UPI. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Goltz, Thomas C. (24 August 1985). "Ex-astronaut searching for Noah's Ark". UPI. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Bright, Richard (1999). "1984-2006 Dick Bright, Ph.D.". In Corbin, B. J. (ed.). The Explorers of Ararat and the Search for Noah's Ark. Great Commission Illustrated Books. pp. 226–273. ISBN 9780965346986.

- ^ Sifford, Darrell (1 June 1986). "Astronaut thinks ark is no myth". Chicago Tribune. p. A5. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Ex-astronaut Irwin continues to improve". UPI. 9 June 1986. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Irwin Plans 5th Bid For Ark". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Alemdar, Zeynep (13 August 1986). "Going to the Mountain". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Ex-Astronaut Irwin Briefly Detained in Turkey With AM-Soviet-Reporter, Bjt". Associated Press. 30 August 1986. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cornuke, Robert; Halbrook, David (2001). In Search of the Lost Mountains of Noah: The Discovery of the Real Mts. of Ararat. Nasvhille: Broadman & Holman. ISBN 0805420541. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Former Astronaut Giving Up Search For Noah's Ark". Associated Press. 14 September 1986. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Astronaut hopes to resume search for Noah's ark". UPI. 30 July 1987. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Trott, William C. (30 July 1987). "Irwin After The Lost Ark". UPI. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Morris, John D. (January 1988). "A Report on the ICR Ararat Expedition, 1987". Acts & Facts. Vol. 17, no. 1. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Sawyer, Rosemary (23 October 1989). "Ex-astronaut foresees cooperative Mars trip". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Chandler, Tye (8 July 2013). "Ark dedication brings big news". Glen Rose Reporter. Glen Rose, Texas. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Shockey, Don (1986). Agri-Dagh (Mount Ararat): The Painful Mountain. Fresno: Pioneer Publishing Company. ISBN 0914330942.

- ^ Davis, Ed. "Ararat adventure and Ark sighting". NoahsArkSearch.com. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Schubert, Frank N. (1992). "The Persian Gulf Command: Lifeline to the Soviet Union". In Fowle, Barry W. (ed.). Builders and Fighters: U.S. Army Engineers in World War II. Fort Belvoir, Virginia: US Army Corps of Engineers. pp. 305–315. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ a b Crouse, Bill (May 1993). "Figment or Fact? The Incredible Discovery of Noah's Ark". The Ararat Report. No. 32. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Rawlinson, Henry (1839). "Notes on a March from Zoháb, at the Foot of Zagros, along the Mountains to Khúzistán (Susiana), and from Thence Through the Province of Luristan to Kirmánsháh, in the Year 1836". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 9. London: John Murray: 26–116. doi:10.2307/1797715. JSTOR 1797715.

- ^ a b Franz, Gordon; Crouse, Bill; Geissler, Rex (12 December 2008). "The Search for Noah's Ark (Critique of 2008 Video Tape produced by the BASE Institute of Colorado Springs, CO. $14.95.)" (PDF). NoahsArkSearch.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Lippard, Jim (1994). "Sun Goes Down In Flames: The Jammal Ark Hoax". Skeptic. Vol. 2, no. 3. pp. 22–23. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Jammal, George. "Hoaxing The Hoaxers: or, The Incredible (phony) Discovery of Noah's Ark". Atheist Alliance International. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Jaroff, Leon (5 July 1993). "Phony Arkaeology". Time. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Cerone, Daniel (30 October 1993). "Admitting 'Noah's Ark' Hoax". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b Mayell, Hillary (27 April 2004). "Noah's Ark Found? Turkey Expedition Planned for Summer". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Govier, Gordon (1 July 2004). "Explorers of Noah's Lost Ark". Christianity Today. Vol. 48, no. 7. Archived from the original on 10 October 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ a b Lovgren, Stefan (20 September 2004). "Noah's Ark Quest Dead in Water – Was It a Stunt?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Seeking Noah's Ark ... In Turkey". CBSNews.com. 26 April 2004. Archived from the original on 28 April 2004. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Paton, Nick (3 May 2004). "Scientists to search for Noah's ark on Turkish mountain". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ a b Adamski, Mary (3 September 2004). "Turkey denies Honolulu man's bid to find Ark". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Chapman, Don (28 December 2011). "Dan McGivern and the Ark". MidWeek. Honolulu. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Howse, Brannon (16 June 2006). "Noah's Ark? For Real". Worldview Weekend. Archived from the original on 3 July 2006.

- ^ a b "Has Noah's Ark Been Found?". ABC News. 29 June 2006. Archived from the original on 6 August 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b Ravilious, Kate (5 July 2006). "Noah's Ark Discovered in Iran?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 8 July 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Noah's Ark". Base Institute. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Jennifer (12 August 2006). "Is Noah's Ark on mount in Iran?". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Franz, Gordon (2 November 2012). "Where are Bob Cornuke's Peer-Reviewed Scientific Publications?". Life and Land. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Brayton, Ed (17 June 2006). "Noah's Ark Found - Again". ScienceBlogs. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Lanser, Rick (19 July 2006). "Noah's Ark in Iran?". Associates for Biblical Research. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Barna, Mark (5 September 2010). "Ark hunter finds fulfillment in aiding orphans". The Gazette. Colorado Springs. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Cornuke, Robert (19 October 2012). Foreword. The Unsolved Mystery of Noah's Ark. By Irwin, Mary. Bloomington, Indiana: WestBow. pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 9781449764760. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ a b Yeung, Winnie (23 November 2004). "HK evangelists join list of Noah's Ark 'discoverers'". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Heifetz, Justin (4 July 2016). "Hong Kong's Bizarre Noah's Ark Theme Park". Roads & Kingdoms. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Song, Christina (20 March 2005). "Media Evangelism Featuring Documentary of 'The Days of Noah'". The Gospel Herald. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Major Events of the Noah's Ark Expedition". NoahsArkSearch.net. Noah's Ark Ministries International. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Wong, Martin (3 October 2007). "Explorers bring traces of 'Noah's ark' to HK". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b Tharoor, Ishaan (29 April 2010). "Has Noah's Ark Been Discovered in Turkey?". Time. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b Than, Ker (30 April 2010). "Noah's Ark Found in Turkey?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b Cheung, Simpson (26 April 2010). "Have Hong Kong evangelists found the biblical Noah's ark?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Exploration Team Successfully Ventures inside 4,800-year old Wooden Structure on Snow-capped Mount Ararat". NoahsArkSearch.net. Noah's Ark Ministries International. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Cathal (27 April 2010). "Noah's Ark found, researchers claim". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ NoahsArkSearch (6 May 2010). Noahs Ark found in Turkey 7 Spaces were Discovered 探索隊新考據,七度空間曝光. YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Cathal (29 April 2010). "Is the latest Noah's Ark discovery a fake?". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (27 April 2010). "Noah's Ark found? Not so fast". NBC News. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Cargill, Robert R. (28 April 2010). "no, no you didn't find noah's ark". XKV8R: The (Retired) Blog of Robert R. Cargill, Ph.D. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.