Wake Island

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2023) |

Wake Island

Ānen Kio (Marshallese) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Where America's Day Really Begins"[1] | |

Map of Wake Island | |

| Coordinates: 19°17′43″N 166°37′52″E / 19.29528°N 166.63111°E | |

| Administered by | |

| Status | Unorganized unincorporated territory |

| Territory | United States Minor Outlying Islands |

| Claimed by | |

| Claimed by the United States | January 17, 1899 |

| Claimed by the Marshall Islands | Oral tradition |

| Government | |

| • Body | United States Air Force (under the authority of the U.S. Department of the Interior) |

| • Civil Administrator | General Counsel of the Air Force PACAF Regional Support Center |

| Area | |

• Total | 13.86 km2 (5.35 sq mi) |

| • Land | 7.38 km2 (2.85 sq mi) |

| • Water | 6.48 km2 (2.5 sq mi) |

| • Lagoon | 5.17 km2 (2.00 sq mi) |

| • EEZ | 407,241 km2 (157,237 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 6 m (21 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Estimate | 0 |

| • Non-permanent residents | c. 100 |

| Demonym | Wakean |

| Time zone | UTC+12:00 (Wake Island Time Zone) |

| APO / Zip Code | 96898 |

Wake Island (Marshallese: Ānen Kio, lit. 'island of the kio flower'), also known as Wake Atoll, is a coral atoll in the Micronesia subregion of the Pacific Ocean. The atoll is composed of three islets – Wake, Wilkes, and Peale Islands – surrounding a lagoon encircled by a coral reef. The nearest inhabited island is Utirik Atoll in the Marshall Islands, located 592 miles (953 kilometers) to the southeast.

The island may have been found by prehistoric Austronesian mariners before its first recorded discovery by Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira in 1568. Ships continued visiting the area in the following centuries, but the island remained undeveloped until the United States claimed it in 1899. Significant development of the island didn't begin until 1935 when Pan American Airways constructed an airfield and hotel, establishing Wake Island as a stopover for trans-Pacific flying boat routes. In December 1941 at the opening of the Pacific Theatre of World War II Japan seized the island where it remained under Japanese occupation until the end of the war in September 1945. In 1972, Pan American Airways ceased using the island for trans-Pacific layovers due to the adoption of the Boeing 747 into their fleet. With the withdrawal of Pan American Airways, the island's administration was taken over by the United States Air Force, which later used the atoll as a processing location for Vietnamese refugees during Operation New Life in 1975.

Wake Island is claimed by the Marshall Islands but is administered by the United States as an unorganized and unincorporated territory and comprises part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands. The island is administered by the Department of the Interior and managed by the United States Air Force. While there are no permanent residents, approximately 300 people are on the island at any given time, primarily military personnel and contractors.

The natural areas of Wake are a mix of tropical trees, scrub, and grasses that have adapted to the limited rainfall. Thousands of hermit crabs and rats live on Wake, and in the past, cats were introduced to help control the rat population, which at one time was estimated at 2 million. The Wake Island rail, a small flightless bird, once lived on the atoll but went extinct during World War II. Many seabird species also visit Wake, although the thick vegetation has caused most birds to nest in a designated bird sanctuary on Wilkes Island. The submerged and emergent lands at Wake Island comprise a unit of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Etymology

[edit]Wake Island derives its name from British sea captain Samuel Wake, who rediscovered the atoll in 1796 while in command of the Prince William Henry.[2][3] The name is sometimes attributed to Captain William Wake, who also is reported to have discovered the atoll from the Prince William Henry in 1792.[4][5]

Peale Island is named for the naturalist Titian Peale, who visited the island in 1841,[6] and Wilkes Island is named for U.S. Naval officer Charles Wilkes, who led the U.S. expedition to Wake Atoll in 1841.[7][8]

History

[edit]

Prehistory

[edit]The presence of the Polynesian rat on the island suggests that Wake was likely visited by Polynesian or Micronesian voyagers at an early date.[9][10] In the Marshallese oral tradition, stories tell of Ānen Kio, or "island of the orange flower," where men would collect albatross bones for tattooing rituals. Dwight Heine speculated that the Marshall Islanders treated Ānen Kio similar to a game preserve for hunting and gathering food and that no one permanently lived there, similar to land usage practices on Bokak Atoll and Bikar Atoll. He also speculated that the islanders may have stopped traveling to Wake Atoll in the mid-1800s, around the time the first missionaries arrived in the Marshalls.[11] However, the atoll's remoteness and lack of fresh water may have prevented permanent pre-modern human habitation, and no ancient artifacts have been discovered.[12]

Early exploration and shipwrecks

[edit]The first recorded discovery of Wake Island was on October 2, 1568, by Spanish explorer and navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira. In 1567, Mendaña and his crew had set off on two ships, Los Reyes and Todos los Santos, from Callao, Peru, on an expedition to search for a gold-rich land in the South Pacific mentioned in Inca tradition. After visiting Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands, the expedition headed north and came upon Wake Island, "a low barren island, judged to be eight leagues in circumference". Since the date, October 2, was the eve of the feast of Saint Francis of Assisi, the captain named it St Francis Island (Spanish: Isla San Francisco ) The ships were in need of water and the crew was suffering from scurvy, but after circling the island it was determined that Wake was waterless and had "not a cocoanut nor a pandanus" and "there was nothing on it but sea-birds, and sandy places covered with bushes."[13][14][15] (It was while attempting to relocate Wake according to Mendaña's description of its coordinates that James Cook first reached the Hawaiian Islands.)[16]

In 1796, Captain Samuel Wake of the merchantman Prince William Henry also came upon Wake Island, naming the atoll for himself. Soon thereafter, the 80-ton fur trading merchant brig Halcyon arrived at Wake and Master Charles William Barkley, unaware of Captain Wake's visit and other prior European contact, named the atoll Halcyon Island in honor of his ship.[17] In 1823, Captain Edward Gardner, while in command of the Royal Navy's whaling ship HMS Bellona, visited an island at 19°15′00″N 166°32′00″E / 19.25000°N 166.53333°E, which he judged to be 20–25 miles (32–40 kilometers) long. The island was "covered with wood, having a very green and rural appearance". This report is considered to be another sighting of Wake Island.[18]

On December 20, 1841, the United States Exploring Expedition, commanded by US Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, arrived at Wake on USS Vincennes and sent several boats to survey the island. Wilkes described the atoll as "a low coral one, of triangular form and eight feet [2.4 m] above the surface. It has a large lagoon in the centre, which was well filled with fish of a variety of species among these were some fine mullet." He also noted that Wake had no fresh water but was covered with shrubs, "the most abundant of which was the tournefortia." The expedition's naturalist, Titian Peale, noted that "the only remarkable part in the formation of this island is the enormous blocks of coral which have been thrown up by the violence of the sea". Peale collected an egg from a short-tailed albatross and added other specimens, including a Polynesian rat, to the natural history collections of the expedition. Wilkes also reported that "from appearances, the island must be at times submerged, or the sea makes a complete breach over it".[19]

Wake Island first received international attention with the wreck of the barque Libelle. On the night of March 4, 1866, the 650-ton iron-hulled Libelle, of Bremen, struck the eastern reef of Wake Island during a gale. Commanded by Captain Anton Tobias, the ship was en route from San Francisco to Hong Kong with a cargo of mercury (quicksilver). After three days of searching and digging on the island for water, the crew recovered a 200 US gallons (760 L) water tank from the wrecked ship. Valuable cargo was also recovered and buried on the island, including some of the 1,000 flasks of mercury, coins, and precious stones. After three weeks with a dwindling water supply and no sign of rescue, the passengers and crew decided to leave Wake and attempt to sail to Guam (the center of the then Spanish colony of the Mariana Islands) on the two remaining boats from Libelle. Twenty-two passengers and some of the crew sailed in the 22-foot (7 m) longboat under the command of First Mate Rudolf Kausch, and the remainder of the crew sailed with Captain Tobias in the 20-foot (6 m) gig. On April 8, 1866, the longboat reached Guam after 13 days of frequent squalls, short rations, and tropical sun. The gig, commanded by the captain, was lost at sea.[20][21]

The Spanish governor of the Mariana Islands, Francisco Moscoso y Lara, welcomed and aided the Libelle shipwreck survivors on Guam. He also ordered the schooner Ana, owned and commanded by his son-in-law George H. Johnston, to be dispatched with first mate Kausch to search for the missing gig and then sail on to Wake Island to confirm the shipwreck story and recover the buried treasure. Ana departed Guam on April 10 and, after two days at Wake Island, found and salvaged the buried coins, precious stones, and a small quantity of the quicksilver.[22][23]

On July 29, 1870, the British tea clipper Dashing Wave, under the command of Captain Henry Vandervord, sailed out of Fuzhou en route to Sydney. On August 31, "the weather was very thick, and it was blowing a heavy gale from the eastward, attended with violent squalls, and a tremendous sea." At 10:30 pm, breakers were seen, and the ship struck the reef at Wake Island. The vessel began to break up overnight, and at 10:00 am, the crew launched the longboat over the leeward side. In the chaos of the evacuation, the captain secured a chart and nautical instruments but no compass. The crew loaded a case of wine, some bread, and two buckets, but no drinking water. Since Wake Island appeared to have neither food nor water, the captain and his 12-man crew quickly departed, crafting a makeshift sail by attaching a blanket to an oar. With no water, each man was allotted a glass of wine daily until a heavy rain shower came on the sixth day. After 31 days of drifting westward in the longboat, they reached Kosrae (Strong's Island) in the Caroline Islands. Captain Vandervord attributed the loss of Dashing Wave to the erroneous way Wake Island "is laid down in the charts. It is very low, and not easily seen even on a clear night."[20][24]

American annexation

[edit]

With the annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and the acquisition of Guam and the Philippines resulting from the conclusion of the Spanish–American War that same year, the United States began to consider unclaimed and uninhabited Wake Island, located approximately halfway between Honolulu and Manila, as a good location for a telegraph cable station and coaling station for refueling warships of the rapidly expanding United States Navy and passing merchant and passenger steamships. On July 4, 1898, United States Army Brigadier General Francis V. Greene of the 2nd Brigade, Philippine Expeditionary Force, of the Eighth Army Corps, stopped at Wake Island and raised the United States flag while en route to the Philippines on the steamship liner SS China.[25]

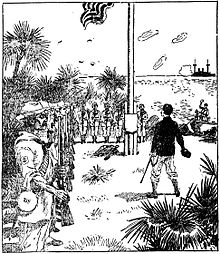

On January 17, 1899, under orders from President William McKinley, Commander Edward D. Taussig of USS Bennington landed on Wake and formally took possession of the island for the United States. After a 21-gun salute, the flag was raised, and a brass plate was affixed to the flagstaff with the following inscription:

- William McKinley, President;

- John D. Long, Secretary of the Navy.

- Commander Edward D. Taussig, U.S.N.,

- Commander U.S.S. Bennington,

- this 17th day of January 1899, took

- possession of the Atoll known as Wake

- Island for the United States of America.[26]

Although the proposed Wake Island route for the submarine cable would have been shorter by 137 miles (220 km), the Midway Islands and not Wake Island was chosen as the location for the telegraph cable station between Honolulu and Guam. Rear Admiral Royal Bird Bradford, chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Equipment, stated before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce on January 17, 1902, that "Wake Island seems at times to be swept by the sea. It is only a few feet above the level of the ocean, and if a cable station were established there, costly work would be required; besides, it has no harbor, while the Midway Islands are perfectly habitable and have a fair harbor for vessels of 18 feet (5 m) draught."[27]

On June 23, 1902, USAT Buford, commanded by Captain Alfred Croskey and bound for Manila, spotted a ship's boat on the beach as it passed closely by Wake Island. Soon thereafter, the Japanese launched the boat on the island and sailed out to meet the transport. The Japanese told Captain Croskey that they had been put on the island by a schooner from Yokohama in Japan and that they were gathering guano and drying fish. The captain suspected they were also engaged in pearl hunting. The Japanese revealed that one of their parties needed medical attention, and the captain determined from their descriptions of the symptoms that the illness was most likely beriberi. They informed Captain Croskey that they did not need any provisions or water and expected the Japanese schooner to return in a month or so. The Japanese declined an offer to be taken on the transport to Manila and were given some medical supplies for the sick man, some tobacco, and a few incidentals.[28]

After USAT Buford reached Manila, Captain Croskey reported the Japanese presence at Wake Island. He also learned that USAT Sheridan had a similar encounter at Wake with the Japanese. The incident was brought to the attention of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles Darling, who at once informed the State Department and suggested that an explanation from the Japanese Government was needed. In August 1902, Japanese Minister Takahira Kogorō provided a diplomatic note stating that the Japanese Government had "no claim whatever to make on the sovereignty of the island, but that if any subjects are found on the island the Imperial Government expects that they should be properly protected as long as they are engaged in peaceful occupations."[29]

Wake Island was now clearly a territory of the United States, but the island was only occasionally visited by passing American ships during this period. One notable visit occurred in December 1906, when U.S. Army General John J. Pershing, later famous as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in western Europe during World War I, stopped at Wake on USAT Thomas and hoisted a 45-star U.S. flag that was improvised out of sail canvas.[30]

Japanese activity

[edit]

With limited freshwater resources, no harbor, and no plans for development, Wake Island remained a remote uninhabited Pacific island in the early 20th century. However, a large seabird population attracted Japanese feather collecting. The global demand for feathers and plumage was driven by the millinery industry and popular European fashion designs for hats, while other demand came from pillow and bedspread manufacturers. Japanese poachers set up camps to harvest feathers on many remote islands in the Central Pacific. The feather trade was primarily focused on Laysan albatross, black-footed albatross, masked booby, lesser frigatebird, great frigatebird, sooty tern and other species of tern. On February 6, 1904, Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans arrived at Wake Island on USS Adams and observed Japanese collecting feathers and catching sharks for their fins. Abandoned feather poaching camps were seen by the crew of the submarine tender USS Beaver in 1922 and USS Tanager in 1923. Although feather collecting and plumage exploitation had been outlawed in the territorial United States, there is no record of any enforcement actions at Wake Island.[31]

In January 1908, the Japanese ship Toyoshima Maru, en route from Tateyama, Japan, to the South Pacific, encountered a heavy storm that disabled the ship and swept the captain and five of the crew overboard. The 36 remaining crew members landed on Wake Island, enduring five months of great hardship, disease, and starvation. In May 1908, the Brazilian Navy training ship Benjamin Constant, while on a voyage around the world, passed by the island and spotted a tattered red distress flag. Unable to land a boat, the crew executed a challenging three-day rescue operation using rope and cable to bring on board the 20 survivors and transport them to Yokohama.[32]

U.S. expeditions

[edit]In his 1921 book Sea-Power in the Pacific: A Study of the American-Japanese Naval Problem, Hector C. Bywater recommended establishing a well-defended fueling station at Wake Island to provide coal and oil for United States Navy ships engaged in future operations against Japan.[33] On June 19, 1922, the submarine tender USS Beaver landed an investigating party to determine the practicality and feasibility of establishing a naval fueling station on Wake Island. Lt. Cmdr. Sherwood Picking reported that from "a strategic point of view, Wake Island could not be better located, dividing as it does with Midway, the passage from Honolulu to Guam into almost exact thirds." He observed that the boat channel was choked with coral heads and that the lagoon was very shallow and not over 15 feet (5 m) in depth, and therefore Wake would not be able to serve as a base for surface vessels. Picking suggested clearing the channel to the lagoon for "loaded motor sailing launches" so that parties on shore could receive supplies from passing ships, and he strongly recommended that Wake be used as a base for aircraft. Picking stated, "If the long heralded trans-Pacific flight ever takes place, Wake Island should certainly be occupied and used as an intermediate resting and fueling port."[34]

In 1923, a joint expedition by the then Bureau of the Biological Survey (in the U.S. Department of Agriculture), the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum and the United States Navy was organized to conduct a thorough biological survey of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, then administered by the Biological Survey Bureau as the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation. On February 1, 1923, Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace contacted Secretary of Navy Edwin Denby to request Navy participation and recommended expanding the expedition to Johnston, Midway and Wake, all islands not administered by the Department of Agriculture. On July 27, 1923, USS Tanager, a World War I minesweeper, brought the Tanager Expedition to Wake Island under the leadership of ornithologist Alexander Wetmore, and a tent camp was established on the eastern end of Wilkes. From July 27 to August 5, the expedition charted the atoll, made extensive zoological and botanical observations, and gathered specimens for the Bishop Museum while the naval vessel under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Samuel Wilder King conducted a sounding survey offshore. Other achievements at Wake included examinations of three abandoned Japanese feather poaching camps, scientific observations of the now extinct Wake Island rail, and confirmation that Wake Island is an atoll, with a group comprising three islands with a central lagoon. Wetmore named the southwest island for Charles Wilkes, who had led the original pioneering United States Exploring Expedition to Wake in 1841. The northwest island was named for Titian Peale, the chief naturalist of that 1841 expedition.[7]

Pan American Airways

[edit]

Juan Trippe, president of the world's then-largest airline, Pan American Airways (PAA), wanted to expand globally by offering passenger air service between the United States and China. To cross the Pacific Ocean, his planes would need to island-hop, stopping at various points for refueling and maintenance. He first tried to plot the route on his globe, but it showed only open sea between Midway and Guam. Next, he went to the New York Public Library to study 19th-century clipper ship logs and charts and he "discovered" a little-known coral atoll, Wake Island. To proceed with his plans at Wake and Midway, Trippe would need to be granted access to each island and approval to construct and operate facilities; however, the islands were not under the jurisdiction of any specific U.S. government entity.[35][36]

Meanwhile, U.S. Navy military planners and the State Department were increasingly alarmed by the Empire of Japan's expansionist attitude and growing belligerence in the Western Pacific. Following World War I, the Council of the League of Nations had granted the South Seas Mandate ("Nanyo") to Japan (which had joined the Allied Powers in the First World War) which included the already Japanese-held Micronesia islands north of the equator that were part of the former colony of German New Guinea of the German Empire; these include the modern nation/states of Palau, The Federated States of Micronesia, The Northern Mariana Islands and The Marshall Islands. In the 1920s and 1930s, Japan restricted access to its mandated territory and began to develop harbors and airfields throughout Micronesia in defiance of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, which prohibited both the United States and Japan from expanding military fortifications in the Pacific islands. With Trippe's planned Pan American Airways aviation route passing through Wake and Midway, the U.S. Navy and the State Department saw an opportunity to project American air power across the Pacific under the guise of a commercial aviation enterprise. On October 3, 1934, Trippe wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, requesting a five-year lease on Wake Island with an option for four renewals. Given the potential military value of PAA's base development, on November 13, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William H. Standley ordered a survey of Wake by USS Nitro and on December 29 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6935, which placed Wake Island and also Johnston, Sand Island at Midway and Kingman Reef under the control of the Department of the Navy. Rear Admiral Harry E. Yarnell designated Wake Island as a bird sanctuary to disguise the Navy's military intentions.[37]

USS Nitro arrived at Wake Island on March 8, 1935, and conducted a two-day ground, marine, and aerial survey, providing the Navy with strategic observations and complete photographic coverage of the atoll. Four days later, on March 12, Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson formally granted Pan American Airways permission to construct facilities at Wake Island.[38]

To construct bases in the Pacific, PAA chartered the 6,700-ton freighter SS North Haven, which arrived at Wake Island on May 9, 1935, with construction workers and the necessary materials and equipment to start to build Pan American facilities and to clear the lagoon for a flying boat landing area. The atoll's encircling coral reef prevented the ship from entering and anchoring in the shallow lagoon. The only suitable location for ferrying supplies and workers ashore was at nearby Wilkes Island; however, the chief engineer of the expedition, Charles R. Russell, determined that Wilkes was too low and, at times, flooded and that Peale Island was the best site for the Pan American facilities. To offload the ship, cargo was lightered (barged) from ship to shore, carried across Wilkes, and then transferred to another barge and towed across the lagoon to Peale Island. Someone had earlier loaded railroad track rails onto North Haven by inspiration, so the men built a narrow-gauge railway to make it easier to haul the supplies across Wilkes to the lagoon. The line used a flatbed car pulled by a tractor. On June 12, North Haven departed for Guam, leaving behind various PAA technicians and a construction crew.[39]

Out in the middle of the lagoon, Bill Mullahey, a swimmer and free diver from Columbia University, was tasked with placing dynamite charges to blast hundreds of coral heads from a 1 mile (1,600 m) long, 300 yards (270 m) wide, 6 feet (2 m) deep landing area for the flying boats.[40] In total some 5 short tons (4.5 metric tons) of dynamite were used over three months on the coral heads in the Wake Atoll lagoon.[41]

On August 17, the first aircraft landing at Wake Island occurred when a PAA flying boat landed in the lagoon on a survey flight of the route between Midway and Wake.[42]

The second expedition of North Haven arrived at Wake Island on February 5, 1936, to complete the construction of the PAA facilities. A five-ton diesel locomotive for the Wilkes Island Railroad was offloaded, and the railway track was extended to run from dock to dock. Across the lagoon on Peale, workers assembled the Pan American Hotel, a prefabricated structure with 48 rooms and wide porches and verandas. The hotel consisted of two wings built out from a central lobby, with each room having a bathroom with a hot-water shower. The PAA facilities staff included a group of Chamorro men from Guam who were employed as kitchen helpers, hotel service attendants, and laborers.[43][44] The village on Peale was nicknamed "PAAville" and was the first "permanent" human settlement on Wake.[45]

By October 1936, Pan American Airways was ready to transport passengers across the Pacific on its small fleet of three Martin M-130 "Flying Clippers". On October 11, the China Clipper landed at Wake on a press flight with ten journalists on board. A week later, on October 18, PAA President Juan Trippe and a group of VIP passengers arrived at Wake on the Philippine Clipper (NC14715). On October 25, the Hawaii Clipper (NC14714) landed at Wake with the first paying airline passengers ever to cross the Pacific. In 1937, Wake Island became a regular stop for PAA's international trans-Pacific passenger and airmail service, with two scheduled flights per week, one westbound from Midway and one eastbound from Guam.[43][44] Pan Am also flew Boeing 314 Clipper flying boats, in addition, the Martin M130.[46]

Wake Island is credited with being one of the early successes of hydroponics, which enabled Pan American Airways to grow vegetables for its passengers, as it was costly to airlift in fresh vegetables and the island lacked natural soil.[47] Pan Am remained in operation up to the day of the first Japanese air raid in December 1941, forcing the U.S. into World War II.[48]

The last flight out was Martin M-130, which had just taken off on the flight to Guam when it was called on the radio about Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II, so it returned to Wake. It was fueled up and was going to do a maritime patrol to search for the Japanese, when the Japanese bombing raid attacked and the aircraft took some light damage during the raid, but two of the air crew were wounded. It was stripped of seats and spare weight and filled with 40 people to evacuate. After three take-off attempts, it got in the air. It flew to Midway, then Pearl Harbor, then back to the US.[49] The flight with passengers and 26 Pan-Am employees left in such a hurry that 1 passenger, 1 employee, and 35 Guam staff were left behind. It departed about two hours after the air raid.[50] Except for one other Marine that a PBY flew out on the December 21, these were the last to leave Wake island before the Japanese capture on the 23rd. The US plan was to resupply Wake with a naval force and evacuate civilians, but the island fell to the Japanese while it was still en route.

Military buildup

[edit]

On February 14, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8682 to create naval defense areas in the central Pacific territories. The proclamation established the "Wake Island Naval Defensive Sea Area", encompassing the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding Wake. "Wake Island Naval Airspace Reservation" was also established to restrict access to the airspace over the naval defense sea area. Only U.S. government ships and aircraft were permitted to enter the naval defense areas at Wake Island unless authorized by the Secretary of the Navy.[51]

In January 1941, the United States Navy began constructing a military base on the atoll. On August 19, the first permanent military garrison, elements of the U.S. Marine Corps' First Marine Defense Battalion,[52] totaling 449 officers and men, were stationed on the island, commanded by Navy Cmdr. Winfield Scott Cunningham.[53] Also on the island were 68 U.S. Naval personnel and about 1,221 civilian workers from the American firm Morrison-Knudsen Corp.[54] The base plan was not complete at the time the war started, and work continued even during the battle of Wake. One shortcoming was that the hangars and bunkers were incomplete, so repairing damaged aircraft during the battle was hard.[55]

In November 1941, VMF-211 embarked 12 of its 24 F4F-3 Wildcats and 13 of its 29 pilots aboard USS Enterprise for movement to Wake Island launching from the carrier and arriving at Wake on December 3.[56]

World War II

[edit]

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese began an assault on Wake Island. At the time, there were about 500 Marines, 1100 civilian contractors, and dozens of Pan-Am airline employees and passengers. Shortly after a bombing raid that killed dozens, the Pan Am Flying Boat took off with the passengers and many employees. Three days later, the Japanese began a multi-ship amphibious invasion led by a cruiser, which was turned away at the loss of two destroyers by Wake's artillery. This action was widely reported as the first American battlefield success of the war. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy began a plan to resupply the island and evacuate the contractors; however, before this could happen, a much larger amphibious invasion took place on the island on December 23, 1941, losing two more ships and additional casualties. The Japanese stationed about 4,000 troops on the island. All but 100 of the POWs were sent away; the ones that remained were executed in 1943 after a U.S. bombing raid. In June 1945, the Allies allowed a Japanese hospital ship to evacuate about 1000 soldiers from Wake. The island was bombed many times by the Allies throughout the war but never invaded; it was surrendered to the U.S. in September 1945.

Battle of Wake Island

[edit]

The battle started with air attacks beginning on December 8, 1941. After three days, a naval assault was attempted but rebuffed on December 11, 1941. The island continued to be bombed, and the Japanese amassed a larger invasion fleet. There was a 50-plane air raid on December 21, 1941. The Japanese returned on December 23, 1941, with a much larger amphibious force and captured the island. The Japanese occupied it until September 1945.

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in Hawaii, the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor), at least 27 Japanese Mitsubishi G3M "Nell" medium bombers flown from bases on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands attacked Wake Island, destroying eight of the 12 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter aircraft belonging to USMC Fighter Squadron 211 on the ground. The Marine garrison's defensive emplacements were left intact by the raid, which primarily targeted the aircraft.[57] On December 9 and 10, there were more air attacks, and two Japanese bombers were shot down. However, the bombing of Wilkes Island detonated an ammunition dump, the Wake hospital was destroyed, and many other buildings were damaged. Meanwhile, the Japanese naval landing force was on its way from Roi in the Japanese-held Marshall Islands and would arrive at Wake on December 11, 1941.[58] On the night of December 10, the US submarine USS Triton engaged an enemy destroyer near Wake while on patrol; it fired torpedoes, but in the battle neither vessel was sunk. This is noted as the first time a U.S. submarine launched its torpedoes in the Pacific war.[59]

The Japanese are known to have lost one of the submarines they sent as part of the operation. Still, it was because two of their submarines accidentally collided with one another on December 17, sinking one. Japanese submarine Ro-66 was on the surface 25 nautical miles (46 km; 29 mi) southwest of Wake Island – bearing 252 degrees from the atoll – to recharge her batteries in a heavy squall in the predawn darkness of December 17, 1941, when her lookouts suddenly sighted Ro-62, also on the surface and recharging batteries.[60][61][62] Both submarines attempted to back off, but it was too late to avoid a collision, and Ro-62 rammed Ro-66 at 20:20 Japan Standard Time.[61][62] Ro-66 sank at 19°10′N 166°28′E / 19.167°N 166.467°E[60] with the loss of 63 lives, including that of the commander of Submarine Division 27.[60][61][62] Ro-62 rescued her three survivors, who had been thrown overboard from her bridge by the collision.[60][61][62]

The American garrison, supplemented by civilian construction workers employed by Morrison-Knudsen Corp., repelled several Japanese landing attempts.[63] An American journalist reported that after the initial Japanese amphibious assault was beaten back with heavy losses on December 11, the American commander was asked by his superiors if he needed anything. Popular legend has it that Major James Devereux sent back the message, "Send us more Japs!" – a reply that became famous.[64][65] After the war, when Major Devereux learned that he had been credited with sending such a message, he pointed out that he had not been the commander on Wake Island and denied sending it. "As far as I know, it wasn't sent at all. None of us was that much of a damn fool. We already had more Japs than we could handle."[66] In reality, Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, USN, was in charge of Wake Island, not Devereux.[67] Cunningham ordered that coded messages be sent during operations. A junior officer had added "send us" and "more Japs" to the beginning and end of a message to confuse Japanese code breakers. This was put together at Pearl Harbor and passed on as part of the message.[68]

On December 12, in the early morning, a four-engined flying boat bombed Wake, but a Wildcat fighter aircraft was able to intercept and shoot it down. Later in the day, they were bombed again by 26 Nell aircraft (G3M twin-engine bombers), one of which was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. An F4F Wildcat on patrol late in the day sank a Japanese submarine that was near Wake. The next air raid was on December 14, which included a bombing raid by several 4-engined flying boats, and later in the day, 30 Nells (G3M) struck the atoll, destroying a Wildcat that was under repair. The island was bombed again on December 15, killing one civilian worker. Wake was bombed again on December 16 by 33 Nells (G3M), and again on the 19th, though in that attack one was shot down by anti-aircraft fire and several more damaged.[55] Before and at the start of hostilities, the waters around Wake were patrolled by two USN submarines, the USS Triton and the USS Tambor.[69] Before the start of the war one of the USS Triton crew members became sick and was dropped off at Wake Island on December 1, 1941. He became a prisoner of war and survived WWII.[70] The Triton was radioed about the start of the war when it surfaced to recharge its batteries and was warned to stay away from the atoll, lest Wake's gunners target it. On December 10, the USS Triton had one engagement with a Japanese destroyer and fired the first US torpedoes of the Pacific War, though it did not sink. It escaped unscathed and went on to serve in the Pacific theater (it was later sunk in 1943).[59] The submarine USS Tambor had to return to its home port in Hawaii in mid-December due to mechanical difficulties and had no engagements.[55]

A PBY Catalina flying boat arrived with mail delivery on December 20, 1941. When it left, one marine was sent away on orders because he was required on Midway, thus Lt. Colonel Bayler became the last person to leave Wake Island before its loss.[71] On December 21, 49 aircraft attacked Wake, striking from a Japanese carrier group.[72] During this time, there was a US Naval force on the way that was going to resupply Wake on December 24, but it did not work as planned as the Japanese 2nd wave took the island on December 23 before this could take place.[72] American and Japanese dead from the fighting between December 8 and 23 were buried on the island.[73]

The U.S. Navy attempted to provide support from Hawaii but suffered great losses at Pearl Harbor. The relief fleet they managed to organize was delayed by bad weather. The isolated U.S. garrison was overwhelmed by a reinforced and greatly superior Japanese invasion force on December 23.[74] American casualties numbered 52 military personnel (Navy and Marine) and approximately 70 civilians killed. Japanese losses exceeded 700 dead, with some estimates ranging as high as 1,000. Wake's defenders sank two Japanese fast transports (P32 and P33) and one submarine and shot down 24 Japanese aircraft. The US relief fleet, en route, on hearing of the island's loss, turned back.[75][76]

In the aftermath of the battle, most of the captured civilians and military personnel were sent to POW camps in Asia. However, the Japanese enslaved some of the civilian laborers and tasked them with improving the island's defenses.[77]

At the end of the battle on December 23, 1,603 people, of whom 1,150 were civilians, were taken prisoner. Three weeks later, all but roughly 350–360 were taken to Japanese prisoner-of-war camps in Asia aboard the Nita Maru (later renamed Chūyō). Many of those who stayed were those who were too badly wounded, and some were civilian contractors who knew how to operate the machinery on the island. A significant source of the prisoner war experience on Wake were the accounts in the commanding officer logs for Wilcox and Russel.[78] In September 1942, another 265 were taken off Wake including Wilcox and Russel; not including those that had died or been executed, that left 98 on the island.[78] With the departure of the officers, their logs of daily prisoners of life on Wake ended. Still, additional facts are known, including a new commanding officer of the island in December 1942. In July 1943, a prisoner of war was executed for stealing food, as ordered by Sakaibara; however, the identity of this POW is unknown. On October 7, 1943, the prisoners of war were executed on order of Sakaibara; they were marched into an anti-tank ditch and executed by machine gun fire.[78] At the end of the war, the Japanese garrison surrendered and said the POWs had been killed in a bombing attack; however, that story broke down when some of the officers wrote notes explaining the true story, and Sakaibara confessed to the mass execution.[78]

Japanese occupation, US air raids, and the POW massacre

[edit]

The island's Japanese garrison was composed of the IJN 65th Guard Unit (2,000 men), Japan Navy Captain Shigematsu Sakaibara and the IJA units, which became the 13th Independent Mixed Regiment (1,939 men) under the command of Col. Shigeji Chikamori.[79] Fearing an imminent invasion, the Japanese reinforced Wake Island with more formidable defenses. The American captives were ordered to build a series of bunkers and fortifications on Wake. The Japanese brought in an 8-inch (200 mm) naval gun which is often incorrectly[80] reported as having been captured in Singapore. The U.S. Navy established a submarine blockade instead of an amphibious invasion of Wake Island. The Japanese-occupied island (called Ōtorishima (大鳥島) or Big Bird Island by them for its birdlike shape)[81] was bombed several times by American aircraft; one of these raids was the first mission for future United States President George H. W. Bush.[82]

The island was also bombed with leaflets and even small rubber rafts, with the idea that someone could escape from the island by sea.[83]

In February 1942, there was a raid attack on Wake, which included naval bombardment and bombing by aircraft. On the first day of the attack on February 23, several targets on the island were struck, and in the waters nearby, two Japanese patrol boats were sunk, and four Japanese seamen recovered.[84] The next day (February 24) a Japanese 4-engine patrol aircraft was shot down 5 miles east of Wake, and another patrol boat was sunk by air attack in addition to also striking targets on Wake island.[84] The raids would continue to reduce the danger of Wake being used as a launching point for a strike on Midway.

From June 1942 to July 1943, many US B-24 raids and photographic recon missions were launched from Midway to Wake, often resulting in air battles between Zeros and bombers. For example, on May 15, 1943, a raid of 7 B-24s made it to Wake to be intercepted by 22 Zeros, with allies losing one B-24 and claiming four kills. In July 1943, a B-24 strike targeting the fuel depots lost another B-24 when intercepted by 20–30 Zeros. The last raid from Midway in 1943 was in July. The next significant attack combined naval bombardment and carrier strike aircraft in the fateful October 1943 raids. In 1944, Wake Island was bombed by PB2Y Coronado flying boats operating from Midway to stop the Japanese garrison from supporting the battle for the Marshall Islands. Once the Kwajalein was taken, Wake was attacked from the newly won base with B-24 raids. This continued until October 1944, thereafter Wake was only bombed a few more times by carrier strike groups usually heading west.[85]

On May 10, 1942, one prisoner was executed for breaking into a store and getting drunk. In September 1942, another 265 POWs were taken off the island, leaving 98, and this was reduced to 97 when another was executed in July 1943.[78]

In March 1943, the Japanese transport ship Suwa Maru was traveling to Wake with over 1000 troops on board. The U.S. submarine USS Tunny torpedoed it, and the ship was taking on water as it approached Wake, so it was beached on the coral reef to avoid sinking.[86]

After a successful American air raid on October 5, 1943, Sakaibara ordered the execution of the remaining 97 (as mentioned, one had been executed in July) captured Americans who remained on the island. They were taken to the northern end of the island, blindfolded and machine-gunned.[87] One prisoner escaped, carving the message "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near where the victims had been hastily buried in a mass grave. This unknown American was soon recaptured and beheaded.[88] The one that escaped created an issue for the Japanese, who had already buried the bodies at the end of the runway under coral sand. They then had to dig up and count all the bodies, confirming that one was missing.[89] This would not be the final resting place, as near the end of the war in August 1945, the bodies were again dug up and reburied at Peacock Point in a mass grave but with multiple wooden crosses.[78] After the war, they were exhumed again and buried at the U.S. National Cemetery of the Pacific.[89]

Later in the war, the Japanese garrison had been almost cut off from supplies and was reduced to the point of starvation. While the islands' sooty tern colony had received some protection as a source of eggs, the Wake Island rail was hunted to extinction by the starving soldiers. Ultimately, about three-quarters of the Japanese garrison perished, and the rest survived only by eating tern eggs, the Polynesian rats, and what scant amount of vegetables they could grow in makeshift gardens among the coral rubble.[90][83] In early 1944, Wake was largely cut off from resupply because the Allies Pacific campaign had moved past Wake, in particular, the Japanese base to the south that had been resupplying Wake was captured in January 1944. In May 1944, the Japanese forces on Wake began rationing food, and the rationing became progressively stricter. To survive the garrison engaged in fishing, growing vegetables, bird eggs, and rats, which were essential food supplies at this time, and sometimes tens of thousands of rats were killed in a single day to stave off starvation.[91]

In June 1945, the Japanese hospital ship Takasago Maru was allowed to visit Wake Island, and it departed with 974 patients. It was boarded and checked both before and after the visit to confirm it was not carrying contraband, and the number of patients was confirmed: 974 Japanese were taken off Wake. On the way to Wake, it was stopped by the USS Murray (DD-576) and on the way back from Wake it was stopped by the USS McDermut II (DD-677) to confirm it was carrying the patients.[92] The condition was recorded first hand by the USS McDermut II, which reported that about 15% of the troops that the Japanese evacuated were extremely sick.[83]

The Pacific War finally came to a close in August 1945, with negotiations opening. The Emperor of Japan announced the surrender to the Japanese people, and the agreement was formally signed on September 2, 1945.

Most of the Wake POWs were liberated from Hirahata Camp 12-B, which switched over from Japanese to American control in late August 1945. About 300 prisoners were included from Wake Island, and a makeshift flag was raised at the camp as they gathered to mark the end of their internment.

Surrender and trial

[edit]

On September 4, 1945, the Japanese garrison surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines under the command of Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson.[93] The garrison, having previously received news that Imperial Japan's defeat was imminent, exhumed the mass grave. The bones were moved to the U.S. cemetery established on Peacock Point after the invasion. Wooden crosses were erected in preparation for the expected arrival of U.S. forces. During the initial interrogations, the Japanese claimed that an American bombing raid mostly killed the remaining 98 Americans on the island. However, some escaped and fought to the death after being cornered on the beach at the north end of Wake Island.[94] Several Japanese officers in American custody committed suicide over the incident, leaving written statements that incriminated Sakaibara.[95] Sakaibara and his subordinate, lieutenant commander Tachibana, were later sentenced to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 18, 1947, while Tachibana's sentence was commuted to life in prison.[96] The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Honolulu's National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at section G, commonly known as Punchbowl Crater.[97] A year after the Wake executions, in 1944, there was the Palawan massacre in which Captain Nagayoshi Kojima ordered the execution of 150 POW when he was told the Allies were near. They were burned alive in trenches, and those who tried to flee were gunned down, but 11 escaped, leading to a death toll of 139. In response, the Allies then realized the Japanese might execute POWs if they thought the Allies were near and began a special mission to liberate POW camps.[98] At the time, the events on Wake in 1943 were unknown, and the U.S. allowed the hospital ship Takasago Maru to visit Wake in June 1945.[92] After the surrender, the POW gravesite was found where they had been buried with crosses at Peacock Point, and the story was that either they had died in a U.S. bombing raid or that they had died in a revolt.[99] At the handover of Wake, 2200 Japanese were on the island, significantly less than at the start, but 974 had just been shipped back to Japan in June 1945. Wake was not cut off until later in the war, but it is estimated that hundreds died during the bombing strikes and from starvation, and many were sick with tuberculosis.[83]

In any case, the Japanese soldiers who had survived were nearly all sent away by November 1, 1945, transported aboard the Hikawa Maru for repatriation. The remaining Japanese troops and the officers were shipped to the U.S. base atoll, but on the route, two of the officers committed suicide, leaving notes describing a POW massacre. Another officer wrote a note describing the same. Finally, the Admiral admitted what he had ordered and accepted blame, leading to two officers' trial in late December.[99] Back on Wake, the bodies were eventually exhumed, including those that had died in the Battle of Wake, to try to make identifications. The task proved too difficult, and they were buried as a group with a memorial listing the names. There was a ceremony in 1953.[89]

Post-World War II military and commercial airfield

[edit]

With the end of hostilities with Japan and the increase in international air travel driven partly by wartime advances in aeronautics, Wake Island became a critical mid-Pacific base for the servicing and refueling of military and commercial aircraft. The United States Navy resumed control of the island, and in October 1945, 400 Seabees from the 85th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at Wake to clear the island of the effects of the war and to build basic facilities for a Naval Air Base. The base was completed in March 1946, and on September 24, Pan Am resumed regular commercial passenger service. The era of the flying boats was nearly over, so Pan Am switched to longer-range, faster, and more profitable airplanes that could land on Wake's new coral runway. Other airlines that established transpacific routes through Wake included British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), Japan Airlines, Philippine Airlines and Transocean Airlines. Due to the substantial increase in the number of commercial flights, on July 1, 1947, the Navy transferred administration, operations, and maintenance of the facilities at Wake to the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA). In 1949, the CAA upgraded the runway by paving over the coral surface and extending its length to 7,000 feet.[41][100] Previously Pan Am was still operating airport at Wake.[101]

In July 1950, the Korean Airlift started, and the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) used the airfield and facilities at Wake as an essential mid-Pacific refueling stop for its mission of transporting men and supplies to the Korean War. By September, 120 military aircraft were landing at Wake per day.[102] On October 15, U.S. President Harry S. Truman and General MacArthur met at the Wake Island Conference to discuss progress and war strategy for the Korean Peninsula. They chose to meet at Wake Island because of its proximity to Korea so that MacArthur would not have to be away from the troops in the field for long.[103]

In September 1952, Typhoon Olive struck, causing 750 people to shelter in World War II bunkers as the island was battered with 150 mph winds.[104][105] Olive, the second typhoon to affect the island since 1935, produced sustained wind speeds of 120 mph (190 km/h) and peak gusts of 142 mph (229 km/h) on the island. Significant flooding was also recorded.[106] Damage was severe; it is estimated that 85% of the island's structures were demolished due to the storm.[107] All of the homes and the island's hotel were destroyed. Additionally, the island's chapel and Quonset huts were destroyed.[105][107] The island's LORAN station, operated by the United States Coast Guard, was also damaged.[108] On September 18, 1952 water and power services were restored.[109] The facilities on the island were fully restored in 1953.[107] The total cost to repair damages caused by Olive amounted to $1.6 million (1952 USD; $13 million 2009 USD).[110] No fatalities occurred on the island, and four injuries were reported. None of the 230 Pan Am employees received injuries.[105] In 1953, the bridge between Peale and Wake Island was rebuilt.[111]

The U.S. Coast Guard Loran station had a staff of about ten people. It operated from 1950 to 1978, with facilities rebuilt on Peale Island by 1958.[112][113] Originally, the staff lived on Wake and commuted to the Loran station on Peale across the bridge; the Loran equipment was in a Quonset hut. However, after 1958, new modern facilities were all built on Peale. The cargo ship USCGC Kukui supported the construction of the new LORAN facilities, arriving at the island in 1957.[111]

Missile Impact Location System

[edit]From 1958 through 1960, the United States installed the Missile Impact Location System (MILS) in the Navy-managed Pacific Missile Range. Later, the Air Force managed Western Range to localize the splashdowns of test missile nose cones. MILS was developed and installed by the same entities that had completed the first phase of the Atlantic and U.S. West Coast SOSUS systems. A MILS installation, consisting of both a target array for precision location and a broad ocean area system for good positions outside the target area, was installed at Wake as part of the system supporting Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) tests. Other Pacific MILS shore terminals were at the Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay supporting Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) tests with impact areas northeast of Hawaii and the other ICBM test support systems at Midway Island and Eniwetok.[114][115][116]

Tanker shipwreck and oil spill

[edit]On September 6, 1967, Standard Oil of California's 18,000-ton tanker SS R.C. Stoner was driven onto the reef at Wake Island by a strong southwesterly wind after the ship failed to moor to the two buoys near the harbor entrance. An estimated six million gallons of refined fuel oil – including 5.7 million gallons of aviation fuel, 168,000 gallons of diesel oil, and 138,600 gallons of bunker C fuel – spilled into the small boat harbor and along the southwestern coast of Wake Island to Peacock Point. The oil spill killed large numbers of fish, and personnel from the FAA and crew members from the ship cleared the area closest to the spill of dead fish.[117][118]

The U.S. Navy salvage team Harbor Clearance Unit Two and Pacific Fleet Salvage Officer Cmdr. John B. Orem flew to Wake to assess the situation. By September 13, the Navy tugs USS Mataco and USS Wandank, salvage ships USS Conserver and USS Grapple, tanker USS Noxubee, and USCGC Mallow, arrived from Honolulu, Guam and Subic Bay in the Philippines, to assist in the cleanup and removal of the vessel. The salvage team pumped and skimmed oil at the boat harbor, which they burned each evening in nearby pits. Recovery by the Navy salvage team of the R.C. Stoner and its remaining cargo, however, was hampered by strong winds and heavy seas.[118]

On September 16, Super Typhoon Sarah made landfall on Wake Island at peak intensity with winds up to 145-knots, causing widespread damage. The storm's intensity significantly accelerated the cleanup effort by clearing the harbor and scouring the coast. However, oil remained embedded in the reef's flat crevices, impregnating the coral. The storm also had broken the wrecked vessel into three sections and, although delayed by rough seas and harassment by blacktip reef sharks, the salvage team used explosives to flatten and sink the remaining portions of the ship that were still above water.[119][120]

U.S. military administration

[edit]

In the early 1970s, higher-efficiency jet aircraft with longer-range capabilities lessened the use of Wake Island Airfield as a refueling stop, and the number of commercial flights landing at Wake declined sharply. Pan Am had replaced many of its Boeing 707s with more efficient 747s, thus eliminating the need to continue weekly stops at Wake. Other airlines began to eliminate their scheduled flights into Wake. In June 1972, the last scheduled Pan Am passenger flight landed at Wake, and in July, Pan Am's last cargo flight departed the island, marking the end of the heyday of Wake Island's commercial aviation history. During this same period, the U.S. military had transitioned to longer-range C-5A and C-141 aircraft, leaving the C-130 as the only aircraft that would continue to use the island's airfield regularly. The steady decrease in air traffic control activities at Wake Island was apparent and was expected to continue.

The last Pan Am passenger flight was in 1972, and the airport was transferred from the FAA to the Department of Defense, however it remained open for emergency landings.[121]

On June 24, 1972, responsibility for the civil administration of Wake Island was transferred from the FAA to the United States Air Force under an agreement between the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of the Air Force. In July, the FAA turned over the administration of the island to the Military Airlift Command (MAC). However, legal ownership stayed with the Department of the Interior. The FAA continued maintaining air navigation facilities and providing air traffic control services. On December 27, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF) General John D. Ryan directed MAC to phase out en-route support activity at Wake Island effective June 30, 1973. On July 1, 1973, all FAA activities ended, and the U.S. Air Force under Pacific Air Forces (PACAF), Detachment 4, 15th Air Base Wing assumed control of Wake Island.[122]

In 1973, Wake Island was selected as a launch site for testing defensive systems against ICBMs under the U.S. Army's Project Have Mill. Air Force personnel on Wake and the Air Force Systems Command (AFSC) Space and Missile Systems Organization (SAMSO) provided support to the Army's Advanced Ballistic Missile Defense Agency (ABMDA). A missile launch complex was activated on Wake, and, from February 13 to June 22, 1974, seven Athena H missiles were launched from the island to the Roi-Namur Test Range at Kwajalein Atoll.[100]

In 1973, Wake Island was claimed by what would become the Republic of the Marshall Islands, based on oral legends.[123]

Vietnam War refugees and Operation New Life

[edit]

In the spring of 1975, the population of Wake Island consisted of 251 military, government, and civilian contract personnel, whose primary mission was to maintain the airfield as a Mid-Pacific emergency runway. With the imminent fall of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces, President Gerald Ford ordered American forces to support Operation New Life, the evacuation of refugees from South Vietnam. The original plans included the Philippines' Subic Bay and Guam as refugee processing centers. Still, due to the high number of Vietnamese seeking evacuation, Wake Island was selected as an additional location.[125]

In March 1975, Island Commander Major Bruce R. Hoon was contacted by PACAF and ordered to prepare Wake for its new mission as a refugee processing center where Vietnamese evacuees could be medically screened, interviewed, and transported to the United States or other resettlement countries. A 60-man civil engineering team was brought in to reopen boarded-up buildings and housing. Two complete MASH units arrived to set up field hospitals, and three Army field kitchens were deployed. A 60-man United States Air Force Security Police team, processing agents from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, and various other administrative and support personnel were also on Wake. Potable water, food, medical supplies, clothing, and other supplies were shipped in.[125]

On April 26, 1975, the first C-141 carrying refugees arrived. The airlift to Wake continued at a rate of one C-141 every hour and 45 minutes, each aircraft with 283 refugees on board. At the peak of the mission, 8,700 Vietnamese refugees were on Wake. When the airlift ended on August 2, a total of about 15,000 refugees had been processed through Wake Island as part of Operation New Life.[125][126]

Commemorative and memorial visits

[edit]

In April 1981, a party of 19 Japanese, including 16 former Japanese soldiers who were at Wake during World War II, visited the island to pay respects for their war dead at the Japanese Shinto Shrine.[41]

On November 3 and 4, 1985, a group of 167 former American prisoners of war (POWs) visited Wake with their wives and children. This was the first such visit by a group of former Wake Island POWs and their families.[127]

On November 24, 1985, a Pan Am Boeing 747, renamed China Clipper II, came through Wake Island on a flight across the Pacific to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the inauguration of Pan American China Clipper Service to the Orient. Author James A. Michener and Lars Lindbergh, grandson of aviator Charles Lindbergh, were among the dignitaries on board the aircraft.[128]

Army missile tests

[edit]Subsequently, the island has been used for strategic defense and operations during and after the Cold War, with Wake Island serving as a launch platform for military rockets involved in testing missile defense systems and atmospheric re-entry trials as part of the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site. Wake's location allows for a safe launch and trajectory over the unpopulated ocean with open space for intercepts.[129]

In 1987, Wake Island was selected as a missile launch site for a Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) program named Project Starlab/Starbird. In 1989, the U.S. Army Strategic Defense Command (USASDC) constructed two launch pads on Peacock Point, as well as nearby support facilities, for the eight-ton, 60 feet (20 m), multi-stage Starbird test missiles. The program involved using electro-optical and laser systems mounted on the Starlab platform in the payload bay of an orbiting Space Shuttle to acquire, track, and target Starbird missiles launched from Cape Canaveral and Wake. After being impacted by mission scheduling delays caused by the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger, the program was canceled in late September 1990 to protect funding for another U.S. Army space-based missile defense program known as Brilliant Pebbles. Although no Starbird missiles were ever launched from Wake Island, the Starbird launch facilities at Wake were modified to support rocket launches for the Brilliant Pebbles program, with the first launch occurring on January 29, 1992. On October 16, a 30 feet (10 m) Castor-Orbus rocket was destroyed by ground controllers seven minutes after its launch from Wake. The program was canceled in 1993.[130][131]

Missile testing activities continued with the Lightweight Exo-Atmospheric Projectile (LEAP) Test Program, another U.S. Army strategic defense project that included the launch of two Aerojet Super Chief HPB rockets from Wake Island. The first launch, on January 28, 1993, reached apogee at 240 miles (390 kilometers) and was a success. On February 11, the second launch reached apogee at 1.2 miles (1.9 kilometers) and was deemed a failure.[132]

Due to the U.S. Army's continued use of the atoll for various missile testing programs, on October 1, 1994, the U.S. Army Space and Strategic Defense Command (USASSDC) assumed administrative command of Wake Island under a caretaker permit from the U.S. Air Force. The USASSDC had been operating on Wake since 1988 when the construction of the Starbird launch and support facilities started. Now under U.S. Army control, the island, which is located 690 miles (1,110 kilometers) north of Kwajalein Atoll, became a rocket launch site for the Kwajalein Missile Range known as the Wake Island Launch Center.[133]

In July 1995, various units of the U.S. military established a camp on Wake Island to provide housing, food, medical care, and social activities for Chinese illegal immigrants as part of Operation Prompt Return (also known as Joint Task Force Prompt Return). The Chinese immigrants were discovered on July 3 on board the M/V Jung Sheng Number 8 when the 160-foot-long vessel was interdicted by the U.S. Coast Guard south of Hawaii. The Jung Sheng had left Canton, China en route to the United States on June 2 with 147 Chinese Illegal Immigrants, including 18 "enforcers", and 11 crew on board. On July 29, the Chinese were transported to Wake Island, where they were cared for by U.S. military personnel, and on August 7, they were safely repatriated to China by commercial air charter. From October 10 to November 21, 1996, military units assigned to Operation Marathon Pacific used facilities at Wake Island as a staging area for the repatriation of another group of more than 113 Chinese illegal immigrants who had been interdicted in the Atlantic Ocean near Bermuda aboard the human smuggling vessel, the Xing Da.[134][135]

U.S. Air Force regains control

[edit]

On October 1, 2002, administrative control and support of Wake Island was transferred from the U.S. Army to the U.S. Air Force's 15th Wing of PACAF based at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. The 15th Wing had previously controlled Wake from July 1, 1973, to September 30, 1994. Although the Air Force was again in control, the Missile Defense Agency would continue operating the Wake Island Launch Center. The U.S. Army's Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site would maintain and operate the launch facilities and provide instrumentation, communications, flight and ground safety, security, and other support.[136]

On August 31, 2006, Wake Island was hit by the Super Typhoon Ioke with sustained winds over 155 mph and gusts of 190; this caused damage to the wildlife and facilities on the atoll.[137] There was considerable damage, but overall it was less than feared on inspection. The runway was largely intact, but some electrical and waste-water systems had been damaged.[137] The golf course at Heel Point and Golf clubhouse was also damaged by the Ioke Typhoon.[138]

On January 6, 2009, President George W. Bush issued Executive Order 8836, establishing Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument to preserve the marine environments around Wake, Baker, Howland, and Jarvis Islands, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef and Palmyra Atoll. The proclamation assigned management of the nearby waters and submerged and emergent lands of the islands to the Department of the Interior and management of fishery-related activities in waters beyond 12 nautical miles from the islands' mean low water line to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).[139] On January 16, Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne issued Order Number 3284 which stated that the area at Wake Island assigned to the Department of Interior by Executive Order 8836 will be managed as a National Wildlife Refuge. Management of the emergent lands at Wake Island by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, however, will not begin until the existing management agreement between the Secretary of the Air Force and the Secretary of the Interior is terminated.[140][141]

The 611th Air Support Group (ASG), a U.S. Air Force unit based at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage, Alaska took over control of Wake Island from the 15th Wing On October 1, 2010. The 611th ASG was already providing support and management to various geographically remote Air Force sites within Alaska, and the addition of Wake Island provided the unit with more opportunities for outdoor projects during the winter months when projects in Alaska are minimal. The 611th ASG, a unit of the 11th Air Force, was renamed the Pacific Air Forces Regional Support Center.[142]

On September 27, 2014, President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 9173 to expand the area of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument out to the full 200 nautical miles U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) boundary for each island. By this proclamation, the area of the monument at Wake Island was increased from 15,085 to 167,336 sq mi (39,070 to 433,400 km2).[143] In 2014, 3300 tons of waste dumps was removed from the islands on barges.[144]

On November 1, 2015, a complex $230 million U.S. military missile defense system test event, called Campaign Fierce Sentry Flight Test Operational-02 Event 2 (FTO-02 E2), was conducted at Wake Island and the surrounding ocean areas. The test involved a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system built by Lockheed Martin, two AN/TPY-2 radar systems built by Raytheon, Lockheed's Command, Control, Battle Management, and Communications system, and USS John Paul Jones guided missile destroyer with its AN/SPY-1 radar. The objective was to test the ability of the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense and THAAD Weapon Systems to defeat a raid of three near-simultaneous air and missile targets, consisting of one medium-range ballistic missile, one short-range ballistic missile and one cruise missile target. During the test, a THAAD system on Wake Island detected and destroyed a short-range target simulating a short-range ballistic missile launched by a C-17 transport plane. At the same time, the THAAD system and the destroyer launched missiles to intercept a medium-range ballistic missile launched by a second C-17.[145][146]

In 2017, Thai contractors and armed forces personnel celebrated the Thai New Year or Songkran in April, and Thai King's Day was celebrated in December.[147] Wake at one point had an estimated 2 million rats, and despite eradication efforts hunting rats at night is popular activity of the islanders.[144][148]

Geography

[edit]| Name | acres | hectares |

|---|---|---|

| Wake Islet | 1,367.04 | 553.22 |

| Wilkes Islet | 197.44 | 79.90 |

| Peale Islet | 256.83 | 103.94 |

| Wake Island (total of all three islets) | 1,821.31 | 737.06 |

| Lagoon (water) | 1,480.00 | 600.00 |

| Sand Flat | 910.00 | 370.00 |

Although Wake Island is officially called an island in its singular form, it is geologically an atoll composed of three islets (Wake, Wilkes, and Peale islets).[149] They enclose a shallow lagoon of 3.3 by 7.7 kilometers (2.1 by 4.8 miles), with average depth of around 1 meter (3.3 feet) and a maximum depth of 4.5 meters (15 feet).[150][151] It is ringed by a sandy beach of around 80 meters (260 feet) wide with an offshore fringing reef.[150] The atoll has an average elevation of about 3.6 meters (12 feet) and maximum elevation of 6.4 meters (21 feet),[150] with a total land area of about 6.5 square kilometers (2.5 square miles).[152]

The island is made of coral and sand, as it sits on a coral reef that grew on the top of a seamount made of the remnants of an old volcano.[153] This is consistent with many islands in the Pacific, which are formed when waves erode extinct volcanoes until they reach the surface of the ocean and coral grows on it, forming an atoll (see also guyot).[154] The island is covered in boulders that average 5–6 feet in diameter (1–2 meters) especially on the southern side of Wake and Wilkes islands.[155]

Wake is located two-thirds of the way from Honolulu to Guam; Honolulu is 2,300 mi (3,700 km) to the east, and Guam 1,510 mi (2,430 km) to the west. Midway Atoll is 1,170 mi (1,880 km) to the northeast. The closest land is the uninhabited Bokak Atoll, 348 mi (560 km) away in the Marshall Islands to the southeast. The atoll is to the west of the International Date Line and in the Wake Island Time Zone (UTC+12), the easternmost time zone of the United States and almost one day ahead of the 50 states.

A shallow channel separates Wake and Peale, while Wilkes is connected to Wake by a causeway. The partially completed submarine channel, which has washed through Wilkes at times, almost splits the island in half.

The atoll has several named capes and points:[38]

- Wilkes Island (Split islet on the south and west)

- Kuku Point (Western Cape of Wilkes)

- Wilkes Channel (a channel to the small port/harbor area on the south side of the island)

- Submarine channel (an artificial channel for a partially completed World War II submarine harbor also called New Channel)[156]

- Peale Island (on the north and west, separated from Wake by a narrow channel)

- Toki Point (Western Cape of Peale)

- Flipper Point (Tip of Peale island land that extends into the lagoon pointing west)

- Wake Island (excluding the islets)[157]

Wake Island - Heel Point (the north cape of Wake islet before it turns towards Peale)

- Peacock Point (the Southern and eastern point of Wake Island)

- Causeway crossing Wilkes Channel to Wilkes Island

Climate

[edit]Wake Island lies in the tropical zone but is subject to periodic temperate storms during the winter. Sea surface temperatures are warm all year long, reaching above 80 °F (27 °C) in summer and autumn. Typhoons occasionally pass over the island.[158] Temperatures range between 65 °F (18 °C) and 95 °F (35 °C) and it gets about 40 inches of rain each year, with the rainy season running from July through October. The island lies in the northeast trade winds of the Pacific.[155]

| Climate data for Wake Island, US (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1953–2004) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

97 (36) |

96 (36) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 83.2 (28.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

84.0 (28.9) |

85.4 (29.7) |

86.8 (30.4) |

88.8 (31.6) |

89.1 (31.7) |

89.4 (31.9) |

89.1 (31.7) |

88.1 (31.2) |

86.0 (30.0) |

84.4 (29.1) |

86.5 (30.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 78.7 (25.9) |

78.3 (25.7) |

78.7 (25.9) |

80.0 (26.7) |

81.4 (27.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

83.4 (28.6) |

83.7 (28.7) |

83.4 (28.6) |

82.8 (28.2) |

81.3 (27.4) |

79.9 (26.6) |

81.2 (27.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 74.2 (23.4) |

73.3 (22.9) |

73.4 (23.0) |

74.5 (23.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

77.9 (25.5) |

77.7 (25.4) |

78.0 (25.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

77.4 (25.2) |

76.5 (24.7) |

75.3 (24.1) |

76.0 (24.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

63 (17) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

64 (18) |

70 (21) |

65 (18) |

65 (18) |

64 (18) |

63 (17) |

61 (16) |

64 (18) |

60 (16) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.64 (42) |

1.48 (38) |

2.07 (53) |

1.50 (38) |

2.03 (52) |

1.78 (45) |

4.10 (104) |

4.38 (111) |

5.91 (150) |

5.18 (132) |

2.39 (61) |

2.14 (54) |

34.60 (879) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 mm) | 9.6 | 8.6 | 11.9 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 18.0 | 18.4 | 19.6 | 18.4 | 14.4 | 13.4 | 172.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA[159] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2[160] | |||||||||||||

Typhoons

[edit]

On October 19, 1940, an unnamed typhoon hit Wake Island with 120 knots (220 km/h) winds. This was the first recorded typhoon to hit the island since observations began in 1935.[161]

Super Typhoon Olive impacted Wake on September 16, 1952, with wind speeds reaching 150 knots (280 km/h). Olive caused major flooding, destroyed approximately 85% of its structures, and caused US$1.6 million in damage.[161]

On September 16, 1967, at 10:40 pm local time, the eye of Super Typhoon Sarah passed over the island. Sustained winds in the eyewall were 130 knots (240 km/h), from the north before the eye and the south afterward. All non-reinforced structures were demolished. There were no serious injuries, and most of the civilian population was evacuated after the storm.[161]

On August 28, 2006, the United States Air Force evacuated all 188 residents and suspended all operations as Category 5 Super Typhoon Ioke headed toward Wake. By August 31 the southwestern eyewall of the storm passed over the island, with winds well over 185 miles per hour (298 km/h),[162] driving a 20 ft (6 m) storm surge and waves directly into the lagoon inflicting major damage.[163] A U.S. Air Force assessment and repair team returned to the island in September 2006 and restored limited function to the airfield and facilities leading ultimately to a full return to normal operations.[164]

Ecology

[edit]

Wake Island is home to the Wake Atoll National Wildlife Refuge[165] and comprises a unit of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Native vegetation communities of Wake Island include scrub, grass, and wetlands. Tournefortia argentia (heliotrope tree) dominated scrublands exist in association with Scaevola taccada (beach cabbage), Cordia subcordata (sea trumpet), and Pisonia grandis. Grassland species include Dactyloctenium aegyptium and Tribulus cistoides. Wetlands are dominated by Sesuvium portulacastrum, and Pemphis acidula is found near intertidal lagoons.[166]

The atoll, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognized as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International for its sooty tern colony, with some 200,000 individual birds estimated in 1999.[167] 56 bird species have been sighted on the atoll.[166] Wilkes Island is largely designated as a bird refuge and includes a field mowed annually to attract sooty terns and other birds that might otherwise seek to nest on the mowed apron of the airfield runway.[168]

Due to human use, several invasive species have become established on the atoll. Feral cats were introduced in the 1960s as pets and for pest control. Eradication efforts began in earnest in 1996 and were deemed successful in 2008.[169] Two species of rat, Rattus exulans (Polynesian rat) and Rattus tanezumi (Asian house rat), have colonized the island. R. tanezumi populations were successfully eradicated by 2014, however, R. exulans persists.[166] Casuarina equisetifolia (ironwood or coastal she-oak) was allegedly planted on Wake Island by Boy Scouts in the 1960s for use as a windbreak. It formed large mono-cultural forests that choked out native vegetation. Concerted efforts to kill the population began in 2017.[170] Other introduced plant species include Cynodon dactylon (Bermuda grass) and Leucaena leucocephala (miracle tree). Non-native species of ants are also found on the atoll.[166] Overall, the island is a mixture of tropical scrub brush and grass with trees; some of the trees are over 25 feet tall (over 7 meters).[155]