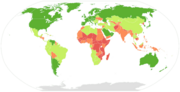

File:Female suicide rates 2015 (crude).svg

Original file (SVG file, nominally 512 × 230 pixels, file size: 1.25 MB)

| This is a file from the Wikimedia Commons. Information from its description page there is shown below. Commons is a freely licensed media file repository. You can help. |

Summary

| DescriptionFemale suicide rates 2015 (crude).svg |

English: Suicide rates per 100,000 females in 2015. Data by World Health Organization (rev. April 2018).

Gender differences in suicide are described since the 1990s, by traditionally higher male suicide rates as contraposed to a typical disproportion of females in nonfatal suicide behavior; a relevant review of previous years' data later mentioned throughout the 2000s, noted this male/female disproportion in suicidality throughout Western countries: the proportion of male suicides was incongruous with that of female suicide attempts, as the male-female ratio of suicides was above 2.4 meaning males completed suicide at least 140% more than females, while the female-male ratio of suicide attempts was 1.5 meaning females attempted suicide 50% more than males. Global average was 1.9 in year 2012 according to the WHO, and 2.0 according to the IHME.[1][2][3] Mortality data is always estimated at a degree. Cited as 'gender paradox of suicidal behavior', it is essentially attributed to post-industrial sociocultural influences and gendered identities: females being more vulnerable to psychological problems and receptive to psychotherapeutic approaches (in western societies mental-health disorders are 20-40% higher in women than men, and female therapists outnumber male) particularly at a young age, report suicide ideation and attempt more frequently and are allowed to discuss their emotions, but males being required to express strength and stoicism assuming social status and working roles crucial for their identity are less likely to seek help for suicidal feelings. Since nonfatal suicidal behavior is typically higher in females while suicide rates are traditionally higher for males, then male vulnerability to suicidal behavior is often explained in terms of higher lethality of suicide methods used and hopelessness, being nevertheless that stigmatization of suicidal behaviors tends to frame surviving a suicidal act and seeking help for mental distress as something ‘inappropriate’ for men: research suggests that the gender gap is partially a result of the choice of more lethal methods and the experience of more aggression, which rather provide an indication of the higher intent to die in men.[4][5][6][7] This gender gap holds true in western cultures, while narrows elsewhere, unto where these patterns are contradicted entirely in various Asian societies (counting almost half of global population). Indeed gender differences in suicide vary significantly among countries: western societies (cultural heritage of european origin, such as european languages or religion) report a higher male mortality by suicide than any other, while South and East Asian a much lower, with China accounting for the greatest number of female suicides.  Wealth is also a constant, being that the gender gap is generally limited or non-existent in low- and middle-income societies, whereas it is never absent in high-income countries (depicted in darker green aside): 200,000 deliberately take their own life in Europe and the Americas every year, about 40,000 females and 150,000 males.[8][9][10] The problem then is not the old-fashioned question — why do so many women commit suicide in China; the actual question is why do so many men commit suicide in high-income countries?[11] In the last 45 years suicide rates have increased by 60% worldwide. An estimated one million people per year die by suicide or a death every 40 seconds or about 3,000 every day (more people die from suicide than from murder and war). At the same time, nonfatal episodes are reported up to 20 times as much, with female adolescents and minority groups (migrants, transgenders, etc.) bearing most relevant socio-economic implications for suicide prevention.[12][13][14]

Late 1890s recorded first gender-related observation on suicide by Émile Durkheim: according to statistics of the time, more men died of suicide than women every year. Also, Durkheim mentioned relations between western industrialization, modern communities and vulnerability to self-destructive behavior, suggesting social norms and pressures have effects on suicide.[10][19] Reinforcement of male gender roles such as strength, independence, risk-taking behavior, often prevents males from seeking help for suicidal feelings and depression.[20][21] It is observed that shifting cultural attitudes about gender roles and social norms and especially ideas about masculinity, may also contribute to closing the gender gap.[5][7][22] Suicidal behavior is also subject of study for economists since about the 1970s: although national costs of suicide and suicide attempts (up to 20 for every one completed suicide) are very high, suicide prevention is hampered by scarce resources for lack of interest by mental health advocates and legislators; and moreover, personal interests even financial are studied with regards to suicide attempts for example, in which insights are given that often "individuals contemplating suicide do not just choose between life and death [..] the resulting formula contains a somewhat paradoxical conclusion: attempting suicide can be a rational choice, but only if there is a high likelihood it will cause the attempter's life to significantly improve."[23][24] In the United States alone, yearly costs of suicide and suicide attempts are comprised in 50-100 billion dollars.[25][26]

Social stigma is considered as well a "major barrier" to suicide prevention, and "the underlying motive for discrimination [..] caused by lack of knowledge - ignorance [..] One extreme example is the criminalization of suicidal behaviour, which still occurs in many countries."[28][29] Per recent releases, the World Health Organization warns about social stigma towards suicidal behavior and psychiatric patients, and the taboo to openly discuss suicide, representing to date challenges and obstacles for suicide prevention policies along with low availability and quality of data.[27]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source |

Based on

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Author | multiple | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other versions |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SVG development InfoField | This vector image was created with Inkscape, or with something else. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Licensing

| This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication. | |

| The person who associated a work with this deed has dedicated the work to the public domain by waiving all of their rights to the work worldwide under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights, to the extent allowed by law. You can copy, modify, distribute and perform the work, even for commercial purposes, all without asking permission.

http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.enCC0Creative Commons Zero, Public Domain Dedicationfalsefalse |

| Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |

| I, the copyright holder of this work, release this work into the public domain. This applies worldwide. In some countries this may not be legally possible; if so: I grant anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law. |

Captions

Items portrayed in this file

depicts

some value

29 August 2018

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 16:11, 22 December 2018 |  | 512 × 230 (1.25 MB) | SuperSucker | fix - brighter yellow (using R-G-B units of 7-24-5 (instead of 7-23-5) |

| 23:57, 21 December 2018 |  | 512 × 230 (1.25 MB) | SuperSucker | fix - better color homogeneity and appropriateness: this proportioning is based on the R-G-B values (units of 7-23-5 respectively) | |

| 18:02, 19 December 2018 |  | 512 × 230 (1.25 MB) | SuperSucker | fix - removed width and height parameters so it automatically resizes to fit the display | |

| 04:05, 3 December 2018 |  | 2,500 × 1,124 (1.25 MB) | SuperSucker | fix - better intervals (five instead of six) and shades | |

| 02:39, 27 October 2018 |  | 2,500 × 1,124 (1.25 MB) | SuperSucker | lighter shades for <15 rates | |

| 19:59, 22 October 2018 |  | 2,500 × 1,124 (1.25 MB) | SuperSucker | cleaned up superfluous svg instructions for an overall lighter file | |

| 21:52, 29 August 2018 |  | 2,500 × 1,124 (1.34 MB) | SuperSucker | User created page with UploadWizard |

File usage

The following 5 pages use this file:

Global file usage

The following other wikis use this file:

- Usage on ar.wikipedia.org

- Usage on as.wikipedia.org

- Usage on ca.wikipedia.org

- Usage on fi.wikipedia.org

- Usage on pt.wikipedia.org

- Usage on sq.wikipedia.org

Metadata

This file contains additional information, probably added from the digital camera or scanner used to create or digitize it.

If the file has been modified from its original state, some details may not fully reflect the modified file.

| Width | 100% |

|---|---|

| Height | 100% |