ECHELON

| Part of a series on |

| Global surveillance |

|---|

| Disclosures |

| Systems |

| Selected agencies |

| Places |

| Laws |

| Proposed changes |

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

ECHELON (Also known as Echelont), originally a secret government code name, is a surveillance program (signals intelligence/SIGINT collection and analysis network) operated by the five signatory states to the UKUSA Security Agreement:[1] Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, also known as the Five Eyes.[2][3][4]

Created in the late 1960s to monitor the military and diplomatic communications of the Soviet Union and its Eastern Bloc allies during the Cold War, the ECHELON project became formally established in 1971.[5][6] By the end of the 20th century, it had greatly expanded.[7]

Organization

[edit]

The UKUSA intelligence community was assessed by the European Parliament (EP) in 2000 to include the signals intelligence agencies of each of the member states:

- the Government Communications Headquarters of the United Kingdom,

- the National Security Agency of the United States,

- the Communications Security Establishment of Canada,

- the Australian Signals Directorate of Australia, and

- the Government Communications Security Bureau of New Zealand.

| Operated by the United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Location | Operator(s) | Codename |

| Brasília, Federal District | SCS | ||

| Bad Aibling, Bavaria | GARLICK[10] | ||

| New Delhi | SCS | ||

| Misawa, Tōhoku region | LADYLOVE[13] | ||

| Bangkok (?) | LEMONWOOD[14] | ||

| Menwith Hill, Harrogate | MOONPENNY[14] | ||

| Sugar Grove, West Virginia | TIMBERLINE[17] | ||

| Yakima, Washington | JACKKNIFE[14] | ||

| Sábana Seca, Puerto Rico | CORALINE[14] | ||

| Operated Jointly with the United States (2nd party) | |||

| Country | Location | Contributor(s) | Codename |

| Geraldton, WA | STELLAR[12] | ||

| Darwin, NT | SHOAL BAY[12] | ||

| Waihopai Station | IRONSAND[12] | ||

| Bude, Cornwall | CARBOY[17] | ||

| Ayios Nikolaos Station | SOUNDER[20] | ||

| Nairobi | SCAPEL[14] | ||

| Seeb, Muscat | SNICK[14] | ||

Reporting and disclosures

[edit]Public disclosures (1972–2000)

[edit]Former NSA analyst Perry Fellwock, under the pseudonym Winslow Peck, first blew the whistle on ECHELON to Ramparts in 1972,[21] when he revealed the existence of a global network of listening posts and told of his experiences working there. He also revealed the existence of nuclear weapons in Israel in 1972, the widespread involvement of CIA and NSA personnel in drugs and human smuggling, and CIA operatives leading Nationalist Chinese (Taiwan) commandos in burning villages inside PRC borders.[22]

In 1982, investigative journalist and author James Bamford wrote The Puzzle Palace, an in-depth history of the NSA and its practices, which notably leaked the existence of the eavesdropping operation Project SHAMROCK. Project SHAMROCK ran from 1945 to 1975, after which it evolved into ECHELON.[23][24]

In 1988, Margaret Newsham, a Lockheed employee under NSA contract, disclosed the ECHELON surveillance system to members of Congress. Newsham told a member of the US Congress that the telephone calls of Strom Thurmond, a Republican US senator, were being collected by the NSA. Congressional investigators determined that "targeting of US political figures would not occur by accident, but was designed into the system from the start."[25]

Also in 1988, an article titled "Somebody's Listening", written by investigative journalist Duncan Campbell in the New Statesman, described the signals intelligence gathering activities of a program code-named "ECHELON".[25] Bamford described the system as the software controlling the collection and distribution of civilian telecommunications traffic conveyed using communication satellites, with the collection being undertaken by ground stations located in the footprint of the downlink leg.[26]

A detailed description of ECHELON was provided by the New Zealand journalist Nicky Hager in his 1996 book Secret Power: New Zealand's Role in the International Spy Network.[27] Two years later, Hager's book was cited by the European Parliament in a report titled "An Appraisal of the Technology of Political Control" (PE 168.184).[28]

In March 1999, for the first time in history, the Australian government admitted that news reports about the top secret UKUSA Agreement were true.[29] Martin Brady, the director of Australia's Defence Signals Directorate (DSD, now known as Australian Signals Directorate, or ASD) told the Australian broadcasting channel Nine Network that the DSD "does co-operate with counterpart signals intelligence organisations overseas under the UKUSA relationship."[30]

In 2000, James Woolsey, the former Director of the US Central Intelligence Agency, confirmed that US intelligence uses interception systems and keyword searches to monitor European businesses.[31]

Lawmakers in the United States feared that the ECHELON system could be used to monitor US citizens.[32] According to The New York Times, the ECHELON system has been "shrouded in such secrecy that its very existence has been difficult to prove."[32] Critics said the ECHELON system emerged from the Cold War as a "Big Brother without a cause".[33]

European Parliament investigation (2000–2001)

[edit]

The program's capabilities and political implications were investigated by a committee of the European Parliament during 2000 and 2001 with a report published in 2001.[7] In July 2000, the Temporary Committee on the ECHELON Interception System was established by the European parliament to investigate the surveillance network.[35] It was chaired by the Portuguese politician Carlos Coelho, who was in charge of supervising investigations throughout 2000 and 2001.

In May 2001, as the committee finalised its report on the ECHELON system, a delegation travelled to Washington, D.C. to attend meetings with US officials from the following agencies and departments:

- US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)[36]

- US Department of Commerce (DOC)[36]

- US National Security Agency (NSA)[36]

All meetings were cancelled by the US government and the committee was forced to end its trip prematurely.[36] According to a BBC correspondent in May 2001, "The US Government still refuses to admit that Echelon even exists."[5]

In July 2001, the Committee released its final report.[37] The EP report concluded that it seemed likely that ECHELON is a method of sorting captured signal traffic, rather than a comprehensive analysis tool.[7] On 5 September 2001, the European parliament voted to accept the report.[38]

The European Parliament stated in its report that the term ECHELON is used in a number of contexts, but that the evidence presented indicates that it was the name for a signals intelligence collection system.[7] The report concludes that, on the basis of information presented, ECHELON was capable of interception and content inspection of telephone calls, fax, e-mail and other data traffic globally through the interception of communication bearers including satellite transmission, public switched telephone networks (which once carried most Internet traffic), and microwave links.[7]

Confirmation of ECHELON (2015)

[edit]Two internal NSA newsletters from January 2011 and July 2012, published as part of Edward Snowden's leaks by the website The Intercept on 3 August 2015, for the first time confirmed that NSA used the code word ECHELON and provided some details about the scope of the program: ECHELON was part of an umbrella program with the code name FROSTING, which was established by the NSA in 1966 to collect and process data from communications satellites. FROSTING had two sub-programs:[39]

- TRANSIENT: for intercepting Soviet satellite transmissions

- ECHELON: for intercepting Intelsat satellite transmissions

The European Parliament's Temporary Committee on the ECHELON Interception System stated, "It seems likely, in view of the evidence and the consistent pattern of statements from a very wide range of individuals and organisations, including American sources, that its name is in fact ECHELON, although this is a relatively minor detail".[7] The US intelligence community uses many code names (see, for example, CIA cryptonym).

Former NSA employee Margaret Newsham said that she worked on the configuration and installation of software that makes up the ECHELON system while employed at Lockheed Martin, from 1974 to 1984 in Sunnyvale, California, in the United States, and in Menwith Hill, England, in the UK.[40] At that time, according to Newsham, the code name ECHELON was NSA's term for the computer network itself. Lockheed called it P415. The software programs were called SILKWORTH and SIRE. A satellite named VORTEX intercepted communications. An image available on the internet of a fragment apparently torn from a job description shows Echelon listed along with several other code names.[41][42]

Britain's The Guardian newspaper summarized the capabilities of the ECHELON system as follows:

A global network of electronic spy stations that can eavesdrop on telephones, faxes and computers. It can even track bank accounts. This information is stored in Echelon computers, which can keep millions of records on individuals. Officially, however, Echelon doesn't exist.[43]

Documents leaked by the former NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed that the ECHELON system's collection of satellite data is also referred to as FORNSAT - an abbreviation for "Foreign Satellite Collection".[44][45]

Intercept stations

[edit]First revealed by the European Parliament report (p. 54 ff)[7] and confirmed later by the Edward Snowden disclosures the following ground stations presently have, or have had, a role in intercepting transmissions from Satellite and other means of communication:[7]

- RAF Little Sai Wan (Closed) (Hong Kong) Map

- Australian Defence Satellite Communications Station (Geraldton, Western Australia) Map

- RAF Menwith Hill (Yorkshire, England – Largest known ECHELON facility)[46] Map

- Misawa Security Operations Center (Oura, Misawa, Aomori, Tōhoku, Japan) Map

- GCHQ Bude (formerly CSO Morwenstow) (Cornwall, UK)[7] Map

- Pine Gap (Outside Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia) Map

- Sugar Grove (Closed) (West Virginia, US) Map

- Yakima Training Center (Closed)[47] (Washington State, US) Map

- Buckley Space Force Base (Aurora, Colorado)[48] Map

- GCSB Waihopai (Marlborough, New Zealand)[49][50] Map

- GCSB Tangimoana (Manawatu-Wanganui, New Zealand)[49] Map

- CFS Leitrim (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada)[51] Map

- Teufelsberg (Closed 1992), *Berlin, Germany[52] – Responsible for listening in to the Eastern Bloc.)[53] Map

- Ayios Nikolaos (British Sovereign Base area of Dhekelia, Cyprus – Cyprus)

- Gibraltar (UK)

- Diego Garcia (UK)

- Bad Aibling Station (Bad Aibling, Germany – US)

- Fort Eisenhower (Georgia, US)

- CFB Gander (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada)[55][56]

- Guam (Pacific Ocean, US)

- Kunia Regional SIGINT Operations Center (Hawaii, US)

- Lackland Air Force Base, Medina Annex (San Antonio, Texas, US)

- RAF Edzell (Closed 1996) (Scotland)[7]

- RAF Boulmer (England)[7]

- SNICK International Processing Center (Seeb, Oman) Map

History and context

[edit]

The ability to intercept communications depends on the medium used, be it radio, satellite, microwave, cellular or fiber-optic.[7] During World War II and through the 1950s, high-frequency ("short-wave") radio was widely used for military and diplomatic communication[57] and could be intercepted at great distances.[7] The rise of geostationary communications satellites in the 1960s presented new possibilities for intercepting international communications.[58] In 1964, plans for the establishment of the ECHELON network took off after dozens of countries agreed to establish the International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (Intelsat), which would own and operate a global constellation of communications satellites.[29]

In 1966, the first Intelsat satellite was launched into orbit. From 1970 to 1971, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) of Britain began to operate a secret signal station at Morwenstow, near Bude in Cornwall, England. The station intercepted satellite communications over the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Soon afterwards, the US National Security Agency (NSA) built a second signal station at Yakima, near Seattle, for the interception of satellite communications over the Pacific Ocean.[29] In 1981, GCHQ and the NSA started the construction of the first global wide area network (WAN). Soon after Australia, Canada, and New Zealand joined the ECHELON system.[29] The report to the European Parliament of 2001 states: "If UKUSA states operate listening stations in the relevant regions of the earth, in principle they can intercept all telephone, fax, and data traffic transmitted via such satellites."[7]

Most reports on ECHELON focus on satellite interception. Testimony before the European Parliament indicated that separate but similar UKUSA systems are in place to monitor communication through undersea cables, microwave transmissions, and other lines.[59] The report to the European Parliament points out that interception of private communications by foreign intelligence services is not necessarily limited to the US or British foreign intelligence services.[7] The role of satellites in point-to-point voice and data communications has largely been supplanted by fiber optics. In 2006, 99% of the world's long-distance voice and data traffic was carried over optical-fiber.[60] The proportion of international communications accounted for by satellite links is said to have decreased substantially to an amount between 0.4% and 5% in Central Europe.[7] Even in less-developed parts of the world, communications satellites are used largely for point-to-multipoint applications, such as video.[61] Thus, the majority of communications can no longer be intercepted by earth stations; they can only be collected by tapping cables and intercepting line-of-sight microwave signals, which is possible only to a limited extent.[7]

Concerns

[edit]British journalist Duncan Campbell and New Zealand journalist Nicky Hager said in the 1990s that the United States was exploiting ECHELON traffic for industrial espionage, rather than military and diplomatic purposes.[59] Examples alleged by the journalists include the gear-less wind turbine technology designed by the German firm Enercon[7][62] and the speech technology developed by the Belgian firm Lernout & Hauspie.[63]

In 2001, the Temporary Committee on the ECHELON Interception System recommended to the European Parliament that citizens of member states routinely use cryptography in their communications to protect their privacy, because economic espionage with ECHELON has been conducted by the US intelligence agencies.[7]

American author James Bamford provides an alternative view, highlighting that legislation prohibits the use of intercepted communications for commercial purposes, although he does not elaborate on how intercepted communications are used as part of an all-source intelligence process.[64]

In its report, the committee of the European Parliament stated categorically that the Echelon network was being used to intercept not only military communications, but also private and business ones. In its epigraph to the report, the parliamentary committee quoted Juvenal, "Sed quis custodiet ipsos custodes." ("But who will watch the watchers").[7] James Bamford, in The Guardian in May 2001, warned that if Echelon were to continue unchecked, it could become a "cyber secret police, without courts, juries, or the right to a defence".[65]

Alleged examples of espionage conducted by the members of the "Five Eyes" include:

- On behalf of the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the Communications Security Establishment allegedly spied on two British cabinet ministers in 1983.[66]

- The US National Security Agency spied on and intercepted the phone calls of Diana, Princess of Wales right up until she died in a Paris car crash with Dodi Fayed in 1997. The NSA currently holds 1,056 pages of classified information about Princess Diana, which has been classified as top secret "because their disclosure could reasonably be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security ... the damage would be caused not by the information about Diana, but because the documents would disclose 'sources and methods' of US intelligence gathering".[67] An official said that "the references to Diana in intercepted conversations were 'incidental'," and she was never a 'target' of the NSA eavesdropping.[67]

- UK agents monitored the conversations of the 7th Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan.[68][69]

- US agents gathered "detailed biometric information" on the 8th Secretary-General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon.[70][71]

- In the early 1990s, the US National Security Agency intercepted the communications between the European aerospace company Airbus and the Saudi Arabian national airline. In 1994, Airbus lost a $6 billion contract with Saudi Arabia after the NSA, acting as a whistleblower, reported that Airbus officials had been bribing Saudi officials to secure the contract.[72] As a result, the American aerospace company McDonnell Douglas (now part of Boeing) won the multibillion-dollar contract instead of Airbus.[73]

- The United States defense contractor Raytheon won a US$1.3 billion contract with the Government of Brazil to monitor the Amazon rainforest after the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), acting as a whistleblower, reported that Raytheon's French competitor Thomson-Alcatel had been paying bribes to get the contract.[74]

- In order to boost the United States position in trade negotiations with the then Japanese Trade Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto, in 1995 the CIA eavesdropped on the conversations between Japanese bureaucrats and executives of car manufacturers Toyota and Nissan.[75]

Workings

[edit]

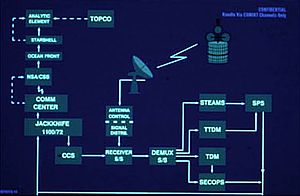

TOPCO = Terminal Operations Control

CCS = Computer Control Subsystem

STEAMS = System Test, Evaluation, Analysis, and Monitoring Subsystem

SPS = Signal Processing Subsystem

TTDM = Teletype Demodulator

The first United States satellite ground station for the ECHELON collection program was built in 1971 at a military firing and training center near Yakima, Washington. The facility, which was codenamed JACKKNIFE, was an investment of ca. 21.3 million dollars and had around 90 people. Satellite traffic was intercepted by a 30-meter single-dish antenna. The station became fully operational on 4 October 1974. It was connected with NSA headquarters at Fort Meade by a 75-baud secure Teletype orderwire channel.[39]

In 1999 the Australian Senate Joint Standing Committee on Treaties was told by Professor Desmond Ball that the Pine Gap facility was used as a ground station for a satellite-based interception network. The satellites were said to be large radio dishes between 20 and 100 meters in diameter in geostationary orbits. The original purpose of the network was to monitor the telemetry from 1970s Soviet weapons, air defence and other radars' capabilities, satellites' ground stations' transmissions and ground-based microwave communications.[77]

Examples of industrial espionage

[edit]In 1999, Enercon, a German company and leading manufacturer of wind energy equipment, developed a breakthrough generator for wind turbines. After applying for a US patent, it had learned that Kenetech, an American rival, had submitted an almost identical patent application shortly before. By the statement of a former NSA employee, it was later claimed that the NSA had secretly intercepted and monitored Enercon's data communications and conference calls and passed information regarding the new generator to Kenetech.[78] However, later German media reports contradicted this story, as it was revealed that the American patent in question was actually filed three years before the alleged wiretapping was said to have taken place.[79] As German intelligence services are forbidden from engaging in industrial or economic espionage, German companies have complained that this leaves them defenceless against industrial espionage from the United States or Russia. According to Wolfgang Hoffmann, a former manager at Bayer, German intelligence services know which companies are being targeted by US intelligence agencies, but refuse to inform the companies involved.[80]

See also

[edit]- Global surveillance disclosures (2013–present)

- ADVISE

- Frenchelon

- List of government surveillance projects

- Mass surveillance

- Onyx (interception system), the Swiss "Echelon"

- Operation Ivy Bells

Bibliography

[edit]- Aldrich, Richard J.; GCHQ: The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency, HarperCollins, July 2010. ISBN 978-0-00-727847-3

- Bamford, James; The Puzzle Palace, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-006748-5; 1983

- Bamford, James; The Shadow Factory: The Ultra-Secret NSA from 9/11 to the Eavesdropping on America, Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-52132-4; 2008

- Hager, Nicky; Secret Power: New Zealand's Role in the International Spy Network; Craig Potton Publishing, Nelson, NZ; ISBN 0-908802-35-8; 1996

- Keefe, Patrick Radden Chatter: Dispatches from the Secret World of Global Eavesdropping; Random House Publishing, New York, NY; ISBN 1-4000-6034-6; 2005

- Keefe, Patrick (2006). Chatter : uncovering the echelon surveillance network and the secret world of global eavesdropping. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8129-6827-9.

- Lawner, Kevin J.; Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe, 14 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 435 (2002)

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Given the 5 dialects that use the terms, UKUSA can be pronounced from "You-Q-SA" to "Oo-Coo-SA", AUSCANNZUKUS can be pronounced from "Oz-Can-Zuke-Us" to "Orse-Can-Zoo-Cuss".

- From Talk:UKUSA Agreement: "Per documents officially released by both the Government Communications Headquarters and the National Security Agency, this agreement is referred to as the UKUSA Agreement. This name is subsequently used by media sources reporting on the story, as written in new references used for the article. The NSA press release provides a pronunciation guide, indicating that "UKUSA" should not be read as two separate entities."(The National Archives)". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (National Security Agency) Archived 16 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine"

- From Talk:UKUSA Agreement: "Per documents officially released by both the Government Communications Headquarters and the National Security Agency, this agreement is referred to as the UKUSA Agreement. This name is subsequently used by media sources reporting on the story, as written in new references used for the article. The NSA press release provides a pronunciation guide, indicating that "UKUSA" should not be read as two separate entities."(The National Archives)". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "UK 'biggest spy' among the Five Eyes". News Corp Australia. 22 June 2013. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Google books – Echelon by John O'Neill

- ^ "AUSCANNZUKUS Information Portal". auscannzukus.net. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Q&A: What you need to know about Echelon". BBC. 29 May 2001. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Nabbali, Talitha; Perry, Mark (March 2004). "Going for the throat". Computer Law & Security Review. 20 (2): 84–97. doi:10.1016/S0267-3649(04)00018-4.

It wasn't until 1971 that the UKUSA allies began ECHELON

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Schmid, Gerhard (11 July 2001). "On the existence of a global system for the interception of private and commercial communications (ECHELON interception system), (2001/2098(INI))". European Parliament: Temporary Committee on the ECHELON Interception System. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Kaz, Roberto; Casado, José (9 July 2013). "Capitais de 4 países também abrigaram escritório da NSA e CIA". O Globo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ a b Gude, Hubert; Poitras, Laura; Rosenbach, Marcel (5 August 2013). "German Intelligence Sends Massive Amounts of Data to the NSA". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Poitras, Laura; Rosenbach, Marcel; Schmid, Fidelius; Stark, Holger; Stock, Jonathan (July 2013). "Cover Story: How the NSA Targets Germany and Europe". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ a b "US spy centre in India too". Deccan Chronicle. 30 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dorling, Philip. "Singapore, South Korea revealed as Five Eyes spying partners". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Document 12. "Activation of Echelon Units," from History of the Air Intelligence Agency, 1 January - 31 December 1994, Volume I (San Antonio, TX: AIA, 1995)". George Washington University.

The second extract notes that AIA's participation in a classified activity "had been limited to LADYLOVE operations at Misawa AB [Air Base], Japan."

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f "Eyes Wide Open" (PDF). Privacy International. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (1 March 2012). "Menwith Hill eavesdropping base undergoes massive expansion". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Steelhammer, Rick (4 January 2014). "In W.Va., mountains of NSA secrecy". The Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ a b Poitras, Laura; Rosenbach, Marcel; Stark, Holger (20 December 2013). "Friendly Fire: How GCHQ Monitors Germany, Israel and the EU". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Troianello, Craig (4 April 2013). "NSA to close Yakima Training Center facility". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hopkins, Nick; Borger, Julian (1 August 2013). "Exclusive: NSA pays £100m in secret funding for GCHQ". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Squires, Nick (5 November 2013). "British military base in Cyprus 'used to spy on Middle East'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ David Horowitz (August 1972). "U.S. Electronic Espionage: A Memoir". Ramparts. 11 (2): 35–50.

- ^ "Ramparts interview". Cryptome archive. 1988. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ Bamford, James (1982). The Puzzle Palace: A Report on America's Most Secret Agency. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-14-006748-4.

- ^ "Puzzle Palace excepts". Cryptome archive. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ a b Campbell, Duncan (12 August 1988). "Somebody's Listening" (PDF). New Statesman. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Bamford, James (2002). Body of Secrets. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-385-49908-8.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (1 June 2001). "Echelon Chronology". Heise Online. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Wright, Steve (6 January 1998). "An Appraisal of Technologies of Political Control" (PDF). European Parliament. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Duncan. "Echelon: World under watch, an introduction". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan; Honigsbaum, Mark (23 May 1999). "Britain and US spy on world". The Observer. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ R. James Woolsey (17 March 2000). "Why We Spy on Our Allies". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b Niall McKay (27 May 1999). "Lawmakers Raise Questions About International Spy Network". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Suzanne Daley (24 February 2000). "An Electronic Spy Scare Is Alarming Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ McCarthy, Kieren (14 September 2001). "This is how we know Echelon exists". The Register. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Rudner, Martin. "Britain betwixt and between: UK SIGINT alliance strategy's transatlantic and European connections". Intelligence & National Security.

- ^ a b c d Roxburgh, Angus (11 May 2001). "EU investigators 'snubbed' in US". BBC. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Report on the existence of a global system for the interception of private and commercial communications (ECHELON interception system) (2001/2098(INI))". European Parliament. 11 July 2001. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "Report: Echelon exists, should be guarded against". USA Today. Associated Press. 5 September 2001. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ a b The Northwest Passage, Yakima Research Station (YRS) newsletter: Volume 2, Issue 1, January 2011 Archived 22 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine & Volume 3, Issue 7, July 2012 Archived 22 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Elkjær, Bo; Seeberg, Kenan (17 November 1999). "ECHELON Was My Baby". Ekstra Bladet. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2006. "Unfortunately, I can't tell you all my duties. I am still bound by professional secrecy, and I would hate to go to prison or get involved in any trouble, if you know what I mean. In general, I can tell you that I was responsible for compiling the various systems and programs, configuring the whole thing and making it operational on mainframes"; "Margaret Newsham worked for the NSA through her employment at Ford and Lockheed from 1974 to 1984. In 1977 and 1978 Newsham was stationed at the largest listening post in the world at Menwith Hill, England ... Ekstra Bladet has Margaret Newsham's stationing orders from the US Department of Defense. She possessed the high security classification TOP SECRET CRYPTO."

- ^ Goodwins, Rupert (29 June 2000). "Echelon: How it works". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (25 July 2000). "Inside Echelon". Heise Online. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Perrone, Jane (29 May 2001). "The Echelon spy network". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Poitras, Laura; Rosenbach, Marcel; Stark, Holger (20 December 2013). "Friendly Fire: How GCHQ Monitors Germany, Israel and the EU". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

A map from the wealth of classified documents obtained by Snowden on the so-called "Fornsat" activities of the technical intelligence cooperation program -- informally known as the Five Eyes -- shows that the system of global satellite surveillance remained in operation.

- ^ Ambinder, Marc (31 July 2013). "What's XKEYSCORE?". The Week. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

FORNSAT simply means "foreign satellite collection," which refers to NSA tapping into satellites that process data used by other countries.

- ^ Le Monde Diplomatique Archived 11 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine, September 2010

- ^ Anderson, Rick (21 June 2013). "Cray and the NSA: Seattle Supercomputers Help Spy Agency Mine Your Megadata". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.

- ^ Troianello, Craig (19 April 2013). "NSA to close Yakima Training Center facility". Yakima Herald-Republic. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ a b Eames, David (19 March 2010). "Waihopai a key link in global intelligence network". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

Both Waihopai and the Tangimoana radio listening post near Palmerston North have been identified as key players in the United States-led Echelon spy programme.

- ^ "GCSB To Remove Dishes And Radomes At Waihopai Station". www.scoop.co.nz. 11 November 2021. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Greisler, David S.; Stupak, Ronald J., eds. (2007). Handbook of technology management in public administration. CRC/Taylor & Francis. p. 592. ISBN 978-1420017014.

- ^ "Teufelsberg mirrors Berlin's dramatic history". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

More than 1,000 people are said to have worked here around the clock, every day of the year. They were part of the global ECHELON surveillance network.

- ^ Beddow, Rachel (19 April 2012). "Teufelsberg, Berlin's Undisputed King of Ghostowns, Set For Redevelopment". NPR. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

The Teufelsberg mission is still shrouded in secrecy, but it's generally agreed that the station was part of the ECHELON network that listened in to the Eastern Bloc.

- ^ According to a statement by Terence Dudlee, the speaker of the US Navy in London, in an interview to the German HR (Hessischer Rundfunk)

"US-Armee lauscht von Darmstadt aus". Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2016. (German), hr online, 1 October 2004 - ^ "CFS Leitrim". Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "canadian military history". Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ The Codebreakers, Ch. 10, 11

- ^ Keefe, Patrick Radden. Chatter: Uncovering the echelon surveillance network and the secret world of global eavesdropping. Random House Incorporated.

- ^ a b For example: "Nicky Hager Appearance before the Euro ean Parliament ECHELON Committee". April 2001. Archived from the original on 21 October 2001. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ^ "NSA eavesdropping: How it might work". CNET News.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ^ "Commercial Geostationary Satellite Transponder Markets for Latin America : Market Research Report". Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ^ Die Zeit: 40/1999 "Verrat unter Freunden" ("Treachery among friends", German), available at "Zeit.de". Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Amerikanen maakten met Echelon L&H kapot". daanspeak.com. 30 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2008. (Google's translation of the article into English Archived 31 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ "The National Security Agency Declassified". nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (9 June 2013). "Our reflection in the N.S.A.'s PRISM" Archived 14 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The New Yorker. Retrieved: 2013-10-12.

- ^ "Thatcher 'spied on ministers'". BBC. 25 February 2000. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ a b Loeb, Vernon (12 December 1998). "NSA Admits to Spying on Princess Diana". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "UK 'spied on UN's Kofi Annan'". BBC. 26 February 2004. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Tyler, Patrick E. (26 February 2004). "Ex-Minister Says British Spies Bugged Kofi Annan's Office". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ "US diplomats spied on UN leadership". The Guardian. 28 November 2010. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Rosenbach, Marcel; Stark, Holger (29 November 2010). "Diplomats or Spooks? How US Diplomats Were Told to Spy on UN and Ban Ki-Moon". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Echelon: Big brother without a cause". BBC News. 6 July 2000. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- ^ "Airbus's secret past". The Economist. 14 June 2003. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ "Big Surveillance Project For the Amazon Jungle Teeters Over Scandals". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ David E. Sanger and Tim Weiner (15 October 1995). "Emerging Role For the C.I.A.: Economic Spy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ The Northwest Passage, Yakima Research Station (YRS) newsletter: Volume 2, Issue 1, January 2011 Archived 22 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Pine Gap" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2016., Official Committee Hansard, Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, 9 August 1999. Commonwealth of Australia.

- ^ Schmid, Gerhard (11 July 2001). "Report on the existence of a global system for the interception of private and commercial communications (ECHELON interception system) (2001/2098(INI))" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Sattar, Majid (July 2013). "NSA-Affäre: Ja, meine Freunde, wir spionieren euch aus!". FAZ.NET (in German). Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Staunton, Denis (16 April 1999). "Electronic spies torture German firms". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

External links

[edit]- Campbell, Duncan (3 August 2015). "GCHQ and Me, My Life Unmasking British Eavesdroppers". The Intercept.

- "Paper 1: Echelon and its role in COMINT". Heise. 27 May 2001.

- Anglosphere

- National Security Agency

- Government databases in the United States

- Privacy in the United States

- Signals intelligence

- Mass surveillance

- Privacy of telecommunications

- Lockheed Martin

- Mass intelligence-gathering systems

- Cyberwarfare

- Surveillance databases

- Global surveillance

- Lockheed Corporation

- Cold War history of Australia