Execution of Charles I

Charles I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, was executed on Tuesday, 30 January 1649[b] outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall, London. The execution was the culmination of political and military conflicts between the royalists and the parliamentarians in England during the English Civil War, leading to the capture and trial of Charles. On Saturday 27 January 1649, the parliamentarian High Court of Justice had declared Charles guilty of attempting to "uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people" and sentenced him to death by beheading.[2]

Charles spent his last few days in St James's Palace, accompanied by his most loyal subjects and visited by his family. On 30 January, he was taken to a large black scaffold constructed in front of the Banqueting House, where he was to be executed. A large crowd had gathered to witness the regicide. Charles stepped onto the scaffold and gave his last speech, declaring his innocence of the crimes of which parliament had accused him, and claiming himself a "martyr of the people". The crowd could not hear the speech, owing to the many parliamentarian guards blocking the scaffold, but Charles's companion, Bishop William Juxon, recorded it in shorthand. Charles gave a few last words to Juxon, claiming an "incorruptible crown" for himself in Heaven, and put his head on the block. He waited a few moments, and after giving a signal that he was ready, the anonymous executioner beheaded Charles with a single blow and held Charles's head up to the crowd silently, dropping it into the swarm of soldiers soon after.

The execution has been described as one of the most significant and controversial events in English history.[c] Some view it as the martyrdom of an innocent man, with Restoration historian Edward Hyde describing "a year of reproach and infamy above all years which had passed before it; a year of the highest dissimulation and hypocrisy, of the deepest villainy and most bloody treasons that any nation was ever cursed with"[3] and the Tory Isaac D'Israeli writing of Charles as "having received the axe with the same collectedness of thought and died with the majesty with which he had lived",[4] dying a "civil and political" martyr to Britain.[5] Still others view it as a vital step towards democracy in Britain, with the prosecutor of Charles I, John Cook, declaring that it "pronounced sentence not only against one tyrant but against tyranny itself"[6][7] and Samuel Rawson Gardiner, a Whig historian, who wrote that "with Charles's death the main obstacle to the establishment of a constitutional system had been removed. [...] The monarchy, as Charles understood it, had disappeared forever".[8]

Execution

[edit]

The execution was set to be carried out on 30 January 1649. On 28 January, the king was moved from the Palace of Whitehall to St James's Palace, likely to avoid the noise of the scaffold being set up outside the Banqueting House (at its rear side on the street of Whitehall).[10] Charles spent the day praying with the Bishop of London, William Juxon.[10]

On 29 January, Charles burnt his personal papers and ciphered correspondence.[11] He had not seen his children for 15 months, so the parliamentarians allowed him to talk to his children, Elizabeth and Henry, for one last time.[12] He instructed the 13-year-old Elizabeth to be faithful to "true Protestant religion" and to tell her mother that "his thoughts had never strayed from her".[13] He instructed the 10-year-old Henry to "not be made a king" by the Parliamentarians, being that many suspected they would install Henry as a puppet king.[14] Charles divided his jewels among the children, leaving him with only his George[15] (an enameled figure of St. George, worn as a part of the ceremonial dress of the Order of the Garter).[16] Charles spent his last night restless, only going to sleep at 2 a.m.[17]

Charles awoke early on the day of his execution. He began dressing at 5 a.m. in fine clothes, all black, and his blue Garter sash.[18] His preparation lasted until dawn.[19] He instructed the Gentleman of the Bedchamber, Thomas Herbert, on what would be done with the few possessions he had left.[20] He requested one extra shirt from Herbert, so that the crowd gathered would not see him shiver from the cold and mistake it for cowardice.[21] Before leaving, Juxon gave Charles the Blessed Sacrament.[22] At 10 a.m., Colonel Francis Hacker instructed Charles to go to Whitehall, ready for his execution.[23] At noon, Charles drank a glass of claret wine and ate a piece of bread, reportedly having been persuaded to this effect by Juxon.[24][22]

A large crowd had amassed outside the Banqueting House, where the platform for Charles's execution was set up.[25] The platform was draped in black and staples had been driven into the wood for ropes to be run through if Charles needed to be restrained.[26] The execution block was so low that the king would have had to prostrate himself to place his head on the block, a submissive pose as compared to kneeling before the block.[27] The executioners of Charles were hidden behind face masks and wigs to prevent identification.[28]

As for the People, truly I desire their liberty and freedom, as much as any whosoever; but I must tell you, that their liberty and freedom consists in having of government by those laws, by which their lives, and their goods may be most their own. It is not for them to have a share in Government, that is nothing Sirs, appertaining unto them. A Subject and a Sovereign are clean different things; and therefore until that be done, I mean, until the people be put into that liberty, which I speak of; certainly they will never enjoy themselves.

Just before 2 p.m., Colonel Hacker called Charles to the scaffold.[30] Charles came through the window of the Banqueting Hall[d] to the scaffold in what Herbert described as "the saddest sight England ever saw".[32][33] Charles saw the crowd and realised that the barrier of guards prevented the crowd from hearing any speech he would make, so he addressed his speech to Juxon and the regicide Matthew Thomlinson, the former of whom recorded the speech in shorthand. He declared that he was innocent of the crimes of which he was accused, that he was faithful to Christianity, and that it was Parliament that had been the cause of the wars leading up to his execution. He called himself "a martyr of the people" - one that would die for their rights.[34][29]

Charles asked Juxon for his silk nightcap to put on, so that the executioner would not be troubled by his hair.[35] He turned to Juxon and declared he "would go from a corruptible crown to an incorruptible crown"[29]—claiming his perceived righteous place in Heaven.[36] Charles gave Juxon his George, sash, and cloak—uttering one cryptic word: "remember".[37] Charles laid his neck out on the block and asked the executioner to wait for his signal to behead him. A moment passed and Charles gave the signal; the executioner beheaded him in one clean blow.[38]

The executioner silently held up Charles's head to the spectators. He did not utter the customary cry of "Behold the head of a traitor!" either from inexperience or fear of identification.[39] According to the royalist Philip Henry, the crowd let out a loud groan[40]—a 17-year-old Henry writing of "such a groan [...] as I never heard before and I desire I may never hear again"[41]—though such a groan is not reported by any other contemporary account of the execution.[42] The executioner dropped the king's head into the crowd and the soldiers swarmed around it, dipping their handkerchiefs in his blood and cutting off locks of his hair.[43] The body was then put in a coffin and covered with black velvet. It was temporarily placed in the king's former 'lodging chamber' within Whitehall.[44]

Executioner

[edit]

The identities of the executioner of Charles I and his assistant were never revealed to the public, with crude face masks and wigs hiding them at the execution,[46] and they were probably only known to Oliver Cromwell and a few of his colleagues.[47] The clean cut on Charles's head and the fact the executioner held up Charles's head after the execution suggests the executioner was experienced in the use of an axe,[48] though the fact the executioner did not call out "Behold the head of a traitor!" could suggest either that he was inexperienced in the public execution of traitors, or that he simply feared identification from his voice.[39]

There was much speculation among the public on the identity of the executioner, with several contradictory identifications appearing in the popular press.[49] These included Richard Brandon, William Hulet, William Walker, Hugh Peter, George Joyce, John Bigg, Gregory Brandon and even—as one French report alleged—Cromwell and Fairfax themselves.[50] Though many of these proved to be unfounded rumours (the accusations of Gregory Brandon, Cromwell, and Fairfax were entirely ahistorical), some may have been accurate.[51]

Colonel John Hewson was given the task of finding an executioner and he offered 40 soldiers the position of executioner or assistant in exchange for £100 and quick promotion, though none came forward immediately.[52] It has been suggested that one of these soldiers later accepted the job, the most probable candidate among the men being Hulet. Shortly after the execution, Hulet received a prominent and swift promotion and he was not seen to be present on the day of Charles's execution. His alibi consisted of the claim he was imprisoned on the day for refusing the position, though this seems to conflict with his promotion soon after.[53] William Hulet was tried as the executioner in October 1660, upon the Restoration, and he was sentenced to death for his supposed part in the execution. This sentence was soon overturned and Hulet was pardoned after some exculpatory evidence was presented to the judge.[54]

Overall, the most likely candidate for the executioner was Richard Brandon, the common hangman at the time of Charles's execution.[55] He would have been experienced, explaining the clean cut, and he is reported to have received £30 around the time of the execution.[56] He was also the executioner of other royalists before, and after, Charles's execution—including William Laud and Lord Capel.[57] Despite this, Brandon denied being the executioner throughout his life, and a contemporary letter claims that he refused a parliamentarian offer of £200 to perform the execution.[58] A tract published shortly after Brandon's death, The Confession of Richard Brandon, claims to contain a deathbed confession of Brandon to the execution of Charles, though it attracted little attention in its time and is now regarded as a forgery.[59][60]

Of the other suggested candidates: Peter had prominently advocated for Charles's death but was absent from his execution, though he was reported to have been kept at home through illness.[61] Joyce was a loyal fanatic of Cromwell and had, earlier in the war, captured the king from Holdenby House.[62] William Walker was a parliamentarian soldier who, according to local tradition, had confessed to the regicide several times.[63] Bigg was a clerk of the regicide Simon Mayne and later hermit who, according to local tradition, became a hermit shortly after the Restoration out of fear for being tried as the executioner.[64]

Reaction

[edit]In Britain

[edit]That thence the Royal actor borne

The tragic scaffold might adorn:

While round the armèd bands

Did clap their bloody hands.

He nothing common did or mean

Upon that memorable scene,

But with his keener eye

The axe's edge did try;

On his execution day, the reports of Charles's last actions were fitting for his later portrayal as a martyr[66]—as biographer Geoffrey Robertson put it, he "played the martyr's part almost to perfection".[67] This was certainly no accident; a flurry of royalist reports overstated the horror of the crowd and the "biblical innocence" of Charles in his execution.[68] Even Charles showed planning for his future martyrdom: apparently delighted that the biblical passage to be read upon the day of his execution was Matthew's account of the Crucifixion. He had hinted to his cousin, the Duke of Hamilton, in 1642:

... yet I cannot but tell you, I have set up my rest upon the Justice of my Cause, being resolved, that no extremity or misfortune shall make me yield; for I will be either a Glorious King, or a Patient Martyr, and as yet not being the first, nor at this present apprehending the other, I think it now no unfit time, to express this my Resolution unto you ...[69]

In the opinion of Daniel P. Klein: "Charles was a defeated and humiliated king in 1649. Yet by tying his trial to Christ's, the King was able to lay claim to martyrdom, connecting his defeated political cause with religious truth."[70]

Almost immediately after Charles was executed,[e] the supposed meditations and autobiography of Charles, Eikon Basilike, began to circulate in England.[71] The book gained massive popularity in a short time, going into twenty editions by the first month of its publication,[73] and has been named by Philip A. Knachel "the most widely read, widely discussed work of royalist propaganda to issue from the English Civil War".[71] The book presented Charles's supposed meditations on the events of his kingship and his justifications for his past actions, widely disseminating the view of Charles as the pious "martyr of the people" he had declared himself to be. It aggravated the fervor of the royalists in the wake of Charles's execution and their high praise led to the wide circulation of the book; some sections even put into verse and music for the uneducated and illiterate of the population.[74] John Milton described it as "the chiefe strength and nerves of their [royalist] cause".[75]

On the other side, the parliamentarians led their own propaganda war against these royalists reports. They suppressed royalist works, among them Eikon Basilike and various other elegies to the deceased king, by arresting and suppressing the printers of such books.[76] Simultaneously, they worked with radical booksellers and publishers to push pro-regicide works, outprinting their opponents by two to one in the month of February, following Charles's execution.[77] John Milton was commissioned to write Eikonoklastes as a parliamentarian rejoinder to Eikon Basilike—sharply mocking the piety of Eikon Basilike and the "image-doting rabble" who latched on to its depiction of Charles, attacking its royalist arguments in a chapter-by-chapter fashion.[78] Charles's prosecutor, John Cook, published a pamphlet defending the execution of Charles, giving "an appeal to all rational men concerning his tryal at the High Court of Justice", in which he asserted that the execution had "pronounced sentence not only against one tyrant but against tyranny itself".[6][7] These publications had such an effect on the public perception that—despite the regicide going against nearly every conception of social order in the period—the regicides of Charles felt safe in their positions soon after.[79] A contemporary source described Cromwell and Ireton as "very cheerfull & well pleased" at the events by 24 February.[80]

In Europe

[edit]

Immediately after the Death of the late King [Charles I], Don Alonso de Cardenas, Embassador from Spain, legitimated this bastard Republick; and Oliver had no sooner made himself Sovereign, under the Quality of Protector, than all the Kings of the Earth prostrated themselves before this Idol.

The reaction among European statesmen was almost universally negative, with the princes and rulers of Europe quick to voice their horror at the regicide.[83] Despite this, very little action was taken against the new English government, as foreign governments carefully avoided cutting off relations with England over their condemnations of the execution. Even the allies of the royalists in the Vatican, France and the Netherlands avoided straining relationships with the parliamentarians in England; the official statement of sympathy to Charles II from the Dutch went as far as possible to avoid calling him "your majesty".[84] Most European nations had their own troubles occupying their minds, such as negotiating the terms of the recently signed Peace of Westphalia, and the regicide was treated with what Richard Bonney described as a "half-hearted irrelevance".[85] As C. V. Wedgwood put it, the general conduct of the statesmen of Europe was to "pay lip-service alone to the idea of avenging the outrage [of the execution], and to govern their conduct towards its perpetrators by purely practical considerations".[86]

One notable exception was the Russian Tsar Alexis, who broke off diplomatic relations with England and accepted royalist refugees in Moscow. He also banned all English merchants from his country (notably members of the Muscovy Company) and provided financial assistance to Charles II, sending his condolences to Henrietta Maria, "the disconsolate widow of that glorious martyr, King Charles I".[87]

In the American colonies

[edit]News of the execution of Charles I travelled slowly to the colonies; on 26 May Roger Williams of Rhode Island reported that "the King and many great Lords and Parliament men are beheaded," and on 3 June Adam Winthrop reported from Boston that "heer is now a London shipp come in, that bringeth the newes that the King is beheaded." However, the initial content of the discussion from letters and diaries remains unclear:

Not until God seemed to signify his approval of the regicide by showering victories on the Commonwealth's armies did public statements of colonial views begin to appear. When Cromwell led the English forces to victory over Charles II and his Scottish supporters at Dunbar in September 1650, the churches of New England celebrated with a day of thanksgiving.

— Francis J. Bremer[88]

Legacy

[edit]

The image of Charles's execution was central to the cult of St. Charles the Martyr, a major theme in English royalism of this period. Shortly after Charles's death, relics of Charles's execution were reported to perform miracles—with handkerchiefs of Charles's blood supposedly curing the King's Evil among peasants.[90] Many elegies and works of devotion were produced to glorify the dead Charles and his cause.[91] After the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, this private devotion was transformed into official worship; in 1661, the Church of England declared 30 January a solemn fast for the martyrdom of Charles and Charles occupied a saint-like status in contemporary prayer books.[92] In Charles II's reign, (as estimated by Francis Turner) around 3000 sermons were given annually to commemorate the martyrdom of Charles.[93] Much Restoration historiography of the Civil War emphasised the regicide as a grand and theatrical tragedy, depicting the last days of Charles's life in a hagiographical fashion. Few saw the executed king's character as fallible.[94] Britain's Lord Chancellor after the Restoration, Edward Hyde, for example, in his monumental History of the Rebellion (1702–1704), was one of the few sometimes critical of Charles's actions and to perceive his flaws as a king,[94] but his account the year of Charles's execution ended with a passionate condemnation of:

...a year of reproach and infamy above all years which had passed before it; a year of the highest dissimulation and hypocrisy, of the deepest villainy and most bloody treasons that any nation was ever cursed with or under; a year in which the memory of all transactions ought to be rased out of all records, lest, by the success of it, atheism, infidelity, and rebellion should be propagated in the world: a year of which we may say, as the historian [Tacitus] said in the time of Domitian, et sicut vetus aetas vidit quid ultimum in libertate esset, ita nos quid in servitute [and just as the former age witnessed how far freedom can go, so we have witnessed how far slavery can][3]

After the Glorious Revolution, even as royalism declined, the cult continued to enjoy support; the anniversaries of Charles's execution created an annual "general madding-day" of Royal support—as Whig Edmund Ludlow put it—up until the 18th-century.[95] Early Whig historians such as James Wellwood and Roger Coke, even as they criticised and mocked the Stuarts, were hesitant to criticise Charles and quick to condemn the execution as an abomination.[96] The memory of Charles's execution remained uncomfortable for many Whigs in Britain.[97] To delegitimise this cult, later Whigs spread the view of Charles as a tyrant, and his execution as a step towards constitutional government in Britain. In opposition, British Tory literary and political figures, including Isaac D'Israeli and Walter Scott, attempted to rejuvenate the cult with romanticised tales of Charles's execution—emphasising the same tropes of martyrdom the royalists had done before them.[98] D'Israeli narrated the execution of Charles I in his Commentaries on the Life and Reign of Charles the First (1828), in which Charles dies "having received the axe with the same collectedness of thought and died with the majesty with which he had lived".[4] For D'Israeli, "the martyrdom of Charles was a civil and political one", which "seems an expiation of the errors and infirmities of the early years of his reign."[5] However, by the Victorian era, the view of the Whig historians had prevailed in British historiography and the public consciousness.[99] The observance of 30 January as the "martyrdom" of Charles was officially removed from the services of the Church of England with the Anniversary Days Observance Act 1859, and the number of sermons given upon the death of Charles I of dwindled.[100] This Whig view was exemplified by the Victorian historian Samuel Rawson Gardiner[101] as he closed his late 19th-century History of the Great Civil War:

Whether the necessity really existed or was but the tyrant's plea is a question upon the answer to which men have long differed, and will probably continue to differ. All can perceive that with Charles's death the main obstacle to the establishment of a constitutional system was removed. Personal rulers might indeed reappear, and Parliament had not yet so displayed its superiority as a governing power to make Englishmen anxious to dispense with monarchy in some form or other. The monarchy, as Charles understood it, had disappeared for ever. Insecurity of tenure would make it impossible for future rulers long to set public opinion at naught, as Charles had done. The scaffold at Whitehall accomplished that which neither the eloquence of Eliot and Pym nor the Statutes and Ordinances of the Long Parliament had been capable of effecting.[102]

Charles I's life and his execution has often been a subject of popular representations in the modern day. Popular historians, such as Samuel Rawson Gardiner, Veronica Wedgwood and J.G. Muddiman, have retold the tale of Charles I's decline and fall, through his trial and to his execution, in narrative histories. Films and television have exploited the dramatic tension and shock of the execution for many purposes: from comedy as in Blackadder: The Cavalier Years, to period drama as in To Kill a King.[103] The subject of the execution, though, has suffered from a notable lack of serious scholarship throughout the modern era; perhaps partly out of what Jason Peacey, a leading figure in the scholarship of Charles I's execution, has called a discomfort at "such a thoroughly 'un-English' project as removing the head of their monarch". This stigma has slowly been lifted, as academic interest has risen into the late 20th century, eliciting much interest in 1999, upon the 350th anniversary of the trial and execution of Charles I.[104]

See also

[edit]- Execution of Louis XVI

- Execution of the Romanov family

- King Charles the Martyr

- Fifth Monarchists

- Charles I Insulted by Cromwell's Soldiers

- Calves' Head Club

Notes

[edit]Explanatory notes

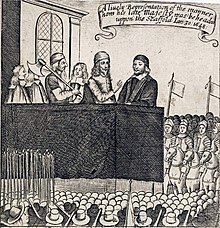

[edit]- ^ This print contains some inaccuracies. The executioner is depicted wearing a dark hood rather than a wig and mask and the depiction of the Banqueting House is inaccurate (compare with Inigo Jones' plan for the building).

- ^ All dates in this article are in the Old Style (Julian calendar) used in Great Britain throughout Charles's lifetime; however, years are assumed to start on 1 January rather than 25 March (Lady Day), which was the English New Year. By New Style format, Charles was executed on 9 February.

- ^ Kelsey 2002, p. 727: "The death of Charles I is an iconic moment in the history of western civilization. It is also central to any attempt to define the nature of the English revolution of 1649"

Worden 2009: "The beheading of Charles I on January 30th, 1649, left an indelible mark on the history of England and on the way that the English think about themselves"

Klein 1997, p. 1 quoting Noel Henning Mayfield: "The trial and execution of Charles Stuart in 1649 stands out in western history. King Charles I was the first European monarch to be put on trial for his life in public by his own subjects. And of course the decline of the British monarchy has played a crucial role in Anglo-American constitutional history" - ^ It is not known which window Charles came through. Some reports even indicate it was not a window but merely a hole in the wall.[31]

- ^ Advanced copies were available on the day of the King's death and the first to go into mass publication were produced in February.[71][72]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "The Execution of King Charles I". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Gardiner, Samuel Rawson, ed. (1906). "The Charge against the King". The Constitutional Documents of the Puritan Revolution 1625–1660. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ a b Hyde, Edward (1706). The History of the Rebellion and the Civil Wars in England, Volume 3, Part 1. Oxford. pp. 273–4.

- ^ a b D'Israeli 1851, p. 574

- ^ a b D'Israeli 1851, p. 566

- ^ a b Quoted in Robertson 2005, p. 194; Wedgwood 1981, p. 2

- ^ a b Cook, John (1649). King Charls, his case, or, An appeal to all rational men concerning his tryal at the High Court of Justice. London: Peter Cole. p. 42.

- ^ Gardiner 1901, p. 329

- ^ "A liuely Representation of the manner how his late Majesty was beheaded uppon the Scaffold Ian 30: 1648: / A representation of the execution of the Kings Judges". The British Museum. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ a b Carlton 1983, p. 355

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 356; Gardiner 1901, p. 319

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 356; Gardiner 1901, p. 319; Wedgwood 1981, p. 166

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 356; Gardiner 1901, p. 319; Wedgwood 1981, p. 167

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 356; Gardiner 1901, p. 319; Wedgwood 1981, pp. 166–168

- ^ Gardiner 1901, pp. 319–320

- ^ Cox, Noel (1999–2000). "The ceremonial dress and accoutrements of the Most Noble Order of the Garter". Archived from the original on 20 April 2003. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 357

- ^ Edwards 1999, pp. 168–169

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 169

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 170; Wedgwood 1981, p. 169

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 357; Robertson 2005, p. 198

- ^ a b Hibbert 1968, p. 278

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 171

- ^ Journal of Robert, 2nd Earl Leicester – Kent Archives U1475/F24 p.38

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 176

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 358; Edwards 1999, p. 176; Hibbert 1968, p. 279; Robertson 2005, p. 198; Wedgwood 1981, p. 177

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 358; Sidney 1905, pp. 97–98

- ^ D'Israeli 1851, p. 559; Edwards 1999, p. 176; Robertson 2005, pp. 198–199; Wedgwood 1981, p. 237

- ^ a b c Charles I (1654). "The Speech of King Charls upon the Scaffold at the gate of White Hall; immediately before the execution. January 30". The full proceedings of the High Court of Iustice against King Charles in Westminster Hall. London.

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 358; Gardiner 1901, p. 322; Robertson 2005, p. 198 Wedgwood 1981, p. 176

- ^ Sidney 1905, pp. 93–94

- ^ Hibbert 1968, p. 279; Robertson 2005, p. 198

- ^ Herbert, Thomas (1815). Memoirs of the Two Last Years of the Reign of King Charles I (3rd ed.). London. p. 193.

- ^ Carlton 1983, pp. 359–360; Edwards 1999, pp. 178–182; Gardiner 1901, p. 322; Hibbert 1968, p. 279; Holmes 2010, p. 93; Robertson 2005, p. 199; Wedgwood 1981, p. 178

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 181; Hibbert 1968, p. 279

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 182; Robertson 2005, p. 200; Wedgwood 1981, p. 176

- ^ Carlton 1983, p. 359; Edwards 1999, p. 182; Robertson 2005, p. 200; Sidney 1905, p. 11; Skerpan-Wheeler 2011, p. 913

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 182; Hibbert 1968, p. 280; Robertson 2005, pp. 200–201; Wedgwood 1981, p. 180

- ^ a b Edwards 1999, p. 183

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 183; Gardiner 1901, p. 323; Wedgwood 1981, p. 181

- ^ Henry, Philip (1882). Lee, Matthew Henry (ed.). Diaries and Letters of Philip Henry. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co. p. 12.

- ^ Robertson 2005, p. 200

- ^ Edwards 1999, pp. 183–184; Hibbert 1968, p. 280; Sidney 1905, p. 62

- ^ Journal of Robert, 2nd Earl of Leicester, Kent Archives, U1475/F24 p.38

- ^ "The confession of Richard Brandon". British Library.

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 176; Robertson 2005, pp. 198–199

- ^ Sidney 1905, p. 41

- ^ Robertson 2005, p. 396

- ^ Edwards 1999, pp. 173–174; Sidney 1905, pp. 42–43

- ^ Edwards 1999, pp. 173–174; Sidney 1905, pp. 43–44; Wedgwood 1981, p. 172

- ^ Sidney 1905, pp. 43–44

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 173; Robertson 2005, p. 332

- ^ Robertson 2005, pp. 332–333

- ^ Sidney 1905, p. 44

- ^ Robertson 2005, pp. 396–397

- ^ Robertson 2005, p. 397

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 173

- ^ Sidney 1905, pp. 60–63

- ^ Robertson 2005, p. 396; Sidney 1905, p. 62; Wedgwood 1981, p. 237

- ^ The Confession of Richard Brandon The Hangman (upon his Death bed) concerning His beheading his late Majesty, Charles the first, King of Great Brittain. London. 1649.

- ^ Sidney 1905, pp. 45–46

- ^ Sidney 1905, pp. 47–48

- ^ Sidney 1905, p. 46

- ^ Sidney 1905, p. 50

- ^ Marvell, A. "An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell's Return from Ireland". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Holmes 2010, pp. 93–94; Lacey 2003, pp. 51–53; Robertson 2005, p. 198; Kelsey 2002, p. 728

- ^ Robertson 2005, p. 198; Gheeraert-Graffeuille 2011

- ^ Robertson 2005, p. 200; Sharpe 2000, pp. 391–394

- ^ Quoted in Wilcher 1991, p. 219

- ^ Klein 1997, p. 18

- ^ a b c Knachel 1966, p. xi

- ^ Skerpan-Wheeler 2011, p. 913

- ^ Knachel 1966, p. xvi

- ^ Knachel 1966, p. xii–xvi; Sharpe 2000, pp. 393–394; Wilcher 1991, pp. 227–228

- ^ Knachel 1966, p. xxii

- ^ Tubb 2004, pp. 505–508

- ^ Tubb 2004, pp. 508–509

- ^ Knachel 1966, p. xxiii–xxv; Skerpan-Wheeler 2011, p. 917

- ^ Tubb 2004, p. 500

- ^ Quoted in Tubb 2004, p. 502

- ^ "The King's Last Day: The Execution of Charles I". National Galleries.

- ^ Quoted in Bonney 2001, p. 247

- ^ Bonney 2001, pp. 247–270; Wedgwood 1965, pp. 431–433

- ^ Wedgwood 1965, pp. 432–435

- ^ Bonney 2001, p. 270

- ^ Wedgwood 1965, p. 446

- ^ Massie, Robert K. Peter the Great: His Life and World. Knopf: 1980. ISBN 0-394-50032-6. p. 12.

- ^ Bremer, Francis J. "In Defense of Regicide: John Cotton on the Execution of Charles I." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 1, 1980, pp. 103–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1920971.

- ^ "'The Apotheosis, or, Death of the King' ('The Beheading of King Charles I')". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Lacey 2003, pp. 60–66; Sharpe 2000, p. 393; Toynbee 1950, pp. 1–14

- ^ Lacey 2001, pp. 225–246; Lacey 2003, pp. 76–129

- ^ Beddard 1984, pp. 36–49; Klein 1997, p. 17; Lacey 2003, pp. 129–140; Sharpe 2000, pp. 394–395; Worden 2009

- ^ Klein 1997, p. 17; Lacey 2003, p. 117

- ^ a b Gheeraert-Graffeuille 2011

- ^ Sharpe 2000, p. 400; Worden 2009

- ^ MacGillivray, R. C. (1974). Restoration Historians and the English Civil War. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 165–170. ISBN 978-90-247-1678-4.

- ^ Worden 2009

- ^ Napton 2018, pp. 148–165

- ^ Napton 2018, p. 149; Worden 2009

- ^ Lacey 2003, p. 117

- ^ Peacey 2001, p. 3

- ^ Gardiner 1901, pp. 329–330

- ^ Peacey 2001, pp. 1–2

- ^ Klein 1997, p. 3; Peacey 2001, pp. 1–4

General sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Carlton, Charles (1983), Charles I: The Personal Monarch, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7100-9485-8

- Edwards, Graham (1999), The Last Days of Charles I, Sutton: Sutton Publishing Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7509-2679-9

- Gardiner, Samuel R. (1901), History of The Great Civil War, 1642–1649: Volume 4, 1647–1649, London: Longmans, Green and Co., OCLC 2567093

- Hibbert, Christopher (1968), Charles I, New York: Harper & Row, OCLC 398731

- Lacey, Andrew (2003), The Cult of King Charles the Martyr, Studies in Modern British Religious History, vol. 7, Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-0-85115-922-5, JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt820jm

- Robertson, Geoffrey (2005), The Tyrannicide Brief: The Story of the Man who sent Charles I to the Scaffold, London: Chatto & Windus, ISBN 978-1-4000-4451-1

- Sidney, Philip (1905), The Headsman of Whitehall, Edinburgh: Geo. A. Morton

- Wedgwood, C. V. (1981), A Coffin for King Charles: The Trial and Execution of Charles I, New York: Time Incorporated, OCLC 1029280370

Articles

[edit]- Beddard, R. A. (1984), "Wren's Mausoleum for Charles I and the Cult of the Royal Martyr", Architectural History, 27: 36–49, doi:10.2307/1568449, JSTOR 1568449, S2CID 195031293

- Bonney, Richard (2001), "The European Reaction to the Trial and Execution of Charles I", in Peacey, Jason (ed.), The Regicides and the Execution of Charles I, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 247–279, ISBN 978-0-333-80259-5

- D'Israeli, Isaac (1851), "The Trial and the Decapitation", in Disraeli, Benjamin (ed.), Commentaries on the Life and Reign of Charles the First, King of England, vol. 2, London: Henry Colburn, pp. 568–573, hdl:2027/nyp.33433075871446, OCLC 717007182

- Gheeraert-Graffeuille, Claire (2011), "The Tragedy of Regicide in Interregnum and Restoration Histories of the English Civil Wars", Études Épistémè, 20 (20), doi:10.4000/episteme.430

- Holmes, Clive (2010), "The Trial and Execution of Charles I", The Historical Journal, 53 (2): 289–316, doi:10.1017/S0018246X10000026, S2CID 159524099

- Kelsey, Sean (2002), "The Death of Charles I", The Historical Journal, 45 (4): 727–754, doi:10.1017/S0018246X02002650, S2CID 159629005

- Klein, Daniel P. (1997), "The Trial of Charles I", The Journal of Legal History, 18 (1): 1–25, doi:10.1080/01440369708531168

- Knachel, Philip A. (1966), Introduction, Eikon Basilike: The Portraiture of his Sacred Majesty in his Solitudes and Sufferings, by Charles I, Folger Documents of Tudor and Stuart Civilization, New York: Cornell University Press, pp. xi–xxxii, OCLC 407343

- Lacey, Andrew (2001), "Elegies and Commemorative Verse in Honour of Charles the Martyr, 1649–60", in Peacey, Jason (ed.), The Regicides and the Execution of Charles I, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 225–246, ISBN 978-0-333-80259-5

- Napton, Dani (2018), "Historical Romance and the Mythology of Charles I in D'Israeli, Scott and Disraeli", English Studies, 99 (2): 148–165, doi:10.1080/0013838X.2017.1420617, S2CID 165213123

- Peacey, Jason (2001), "Introduction", in Peacey, Jason (ed.), The Regicides and the Execution of Charles I, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–13, ISBN 978-0-333-80259-5

- Sharpe, Kevin (2000), "'So Hard a Text'? Images of Charles I, 1612-1700", The Historical Journal, 43 (2): 383–405, doi:10.1017/S0018246X99001132, JSTOR 3021034, S2CID 159780150

- Skerpan-Wheeler, Elizabeth (2011), "The First 'Royal': Charles I as Celebrity", PMLA, 126 (4): 912–934, doi:10.1632/pmla.2011.126.4.912, JSTOR 41414167, S2CID 153380267

- Toynbee, M. R. (1950), "Charles I and the King's Evil", Folklore, 61 (1): 1–14, doi:10.1080/0015587X.1950.9717968, JSTOR 1257298

- Tubb, Amos (2004), "Printing the Regicide of Charles I", History, 89 (4): 500–524, doi:10.1111/j.0018-2648.2004.t01-1-00310.x, JSTOR 24427624

- Wedgwood, C. V. (1965), "European Reaction to the Death of Charles I", The American Scholar, 34 (3): 431–446, JSTOR 41209297

- Wilcher, Robert (1991), "What Was the King's Book for?: The Evolution of 'Eikon Basilike'", The Yearbook of English Studies, 21: 218–228, doi:10.2307/3508490, JSTOR 3508490

- Worden, Blair (February 2009), "The Execution of Charles I", History Today, 59 (2)

External links

[edit] Media related to The Execution of Charles I of England at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Execution of Charles I of England at Wikimedia Commons