Evolution and the Catholic Church

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| History | ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Rejection of evolution by religious groups | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

| Part of a series on |

| Intelligent design |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| Movement |

| Campaigns |

| Authors |

| Organisations |

| Reactions |

|

|

| Creationism |

The Catholic Church holds no official position on the theory of creation or evolution, leaving the specifics of either theistic evolution or literal creationism to the individual within certain parameters established by the Church. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, any believer may accept either literal or special creation within the period of an actual six-day, twenty-four-hour period, or they may accept the belief that the earth evolved over time under the guidance of God. Catholicism holds that God initiated and continued the process of his creation, that Adam and Eve were real people,[1][2] and that all humans, whether specially created or evolved, have and have always had specially created souls for each individual.[3][4]

Early contributions to biology were made by Catholic scientists such as the Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel. Since the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859, the attitude of the Catholic Church on the theory of evolution has slowly been refined. For nearly a century, the papacy offered no authoritative pronouncement on Darwin's theories. In the 1950 encyclical Humani generis, Pope Pius XII confirmed that there is no intrinsic conflict between Christianity and the theory of evolution, provided that Christians believe that God created all things and that the individual soul is a direct creation by God and not the product of purely material forces.[5] Today[update], the Church supports theistic evolution, also known as evolutionary creation.[6]

Catholic schools teach evolution as part of their science curriculum. They teach the fact that evolution occurs and that modern evolutionary synthesis is how evolution proceeds.

Early contributions to evolutionary theory

[edit]

Catholics' contributions to the development of evolutionary theory included those of the Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel (1822-1884). Mendel entered the Brno Augustinian monastery in 1843, but also trained as a scientist at the Olmutz Philosophical Institute and at the University of Vienna. The Brno monastery was a centre of scholarship, with an extensive library and tradition of scientific research.[7] At the monastery, Mendel discovered the basis of genetics following long study of the inherited characteristics of pea plants, although his paper Experiments on Plant Hybridization, published in 1866, remained largely overlooked until the start of the next century.[8]

He developed mathematical formulae to explain the occurrence, and confirmed the results in other plants. Where Darwin's theories suggested a mechanism for improvement of species over generations, Mendel's observations provided explanation for how a new species itself could emerge. Though Darwin and Mendel never collaborated, they were aware of each other's work (Darwin read a paper by Wilhelm Olbers Focke which extensively referenced Mendel). Bill Bryson writes that "without realizing it, Darwin and Mendel laid the groundwork for all of life sciences in the twentieth century. Darwin saw that all living things are connected, that ultimately they trace their ancestry to a single, common source; Mendel's work provided the mechanism to explain how that could happen".[9] Biologist J. B. S. Haldane and others brought together the principles of Mendelian inheritance with Darwinian principles of evolution to form the field of genetics known as the modern evolutionary synthesis.[10]

Changing awareness of the age of the Earth and fossil records helped in the development of evolutionary theory. The work of the Danish scientist Nicolas Steno (1638-1686), who converted to Catholicism and became a bishop, helped establish the science of geology, leading to modern scientific measurements of the age of the Earth.[11]

Early reaction to Charles Darwin's theories

[edit]Catholic concern about evolution has always been very largely concerned with the implications of evolutionary theory for the origin of the human species; even by 1859, a literal reading of the Book of Genesis had long been undermined by developments in geology and other fields.[12] No high-level Church pronouncement has ever attacked head-on the theory of evolution as applied to non-human species[13] although a bishop of the church did excommunicate Gregorio Chil y Naranjo for his scientific work defending Darwin and Lamarck.[14]

Even before the development of modern scientific method, Catholic theology had allowed for biblical text to be read as allegorical, rather than literal, where it appeared to contradict that which could be established by science or reason. Thus Catholicism has been able to refine its understanding of scripture in light of scientific discovery.[15][16] Among the early Church Fathers there was debate over whether God created the world in six days, as Clement of Alexandria taught,[17] or in a single moment as held by Augustine,[18] and a literal interpretation of Genesis was normally taken for granted in the Middle Ages and later, until it was rejected in favour of uniformitarianism (entailing far greater timeframes) by a majority of geologists in the 19th century.[19] However, modern literal creationism has had little support among the higher levels of the Church.

The Catholic Church delayed official pronouncements on Darwin's Origin of Species for many decades.[20] While many hostile comments were made by local clergy, Origin of Species was never placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum;[21] in contrast, Henri Bergson's non-Darwinian Creative Evolution (1907) was on the Index from 1948 until the Index was abolished in 1966.[22] However, a number of Catholic writers who published works specifying how evolutionary theory and Catholic theology might be reconciled ran into trouble of some sort with the Vatican authorities.[23] According to the historian of science and theologian Barry Brundell: "Theologians and historians of science have always been struck by the seemingly enigmatic response of Rome when it did come; the authorities were obviously unhappy with the propagation of 'Christianized evolution', but it seems they were not willing or able to say so straight out and in public".[24] H.L. Mencken observed that:

[The advantage of Catholics] lies in the simple fact that they do not have to decide either for Evolution or against it. Authority has not spoken on the subject; hence it puts no burden upon conscience, and may be discussed realistically and without prejudice. A certain wariness, of course, is necessary. I say that authority has not spoken; it may, however, speak tomorrow, and so the prudent man remembers his step. But in the meanwhile there is nothing to prevent him examining all available facts, and even offering arguments in support of them or against them—so long as those arguments are not presented as dogma.[25]

19th century reception among Catholics

[edit]The first notable statement after Darwin published his theory in 1859 appeared in 1860 from a council of the German bishops, who pronounced:

Our first parents were formed immediately by God. Therefore we declare that the opinion of those who do not fear to assert that this human being, man as regards his body, emerged finally from the spontaneous continuous change of imperfect nature to the more perfect, is clearly opposed to Sacred Scripture and to the Faith.[26]

The concentration of concern on the implications of evolutionary theory for the human species was to remain typical of Catholic reactions. No Vatican response was made to this, which some have taken to imply agreement.[27] No mention of evolution was made in the pronouncements of the First Vatican Council in 1868. In the following decades, a consistently and aggressively anti-evolution position was taken by the influential Jesuit periodical La Civiltà Cattolica, which, though unofficial, was generally believed to have accurate information about the views and actions of the Vatican authorities.[28] The opening in 1998 of the Archive of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (in the 19th century called the Holy Office and the Congregation of the Index) has revealed that on many crucial points this belief was mistaken, and the periodical's accounts of specific cases, often the only ones made public, were not accurate. The original documents show the Vatican's attitude was much less fixed than appeared to be the case at the time.[29]

In 1868, John Henry Newman, later to be made Cardinal, corresponded with a fellow priest regarding Darwin's theory and made the following comments:

As to the Divine Design, is it not an instance of incomprehensibly and infinitely marvellous Wisdom and Design to have given certain laws to matter millions of ages ago, which have surely and precisely worked out, in the long course of those ages, those effects which He from the first proposed. Mr. Darwin's theory need not then to be atheistical, be it true or not; it may simply be suggesting a larger idea of Divine Prescience and Skill. Perhaps your friend has got a surer clue to guide him than I have, who have never studied the question, and I do not [see] that 'the accidental evolution of organic beings' is inconsistent with divine design—It is accidental to us, not to God.[30]

In 1894 a letter was received by the Holy Office, asking for confirmation of the Church's position on a theological book of generally Darwinist cast by a French Dominican theologian, L'évolution restreinte aux espèces organiques, par le père Léroy dominicain. The records of the Holy Office reveal lengthy debates, with a number of experts consulted, whose views varied considerably. In 1895 the Congregation decided against the book, and Fr. Léroy was summoned to Rome, where it was explained that his views were unacceptable, and he agreed to withdraw the book. No decree was issued against Léroy's book, and consequently the book was never placed on the Index.[31] Again, the concerns of the experts had concentrated entirely on human evolution.[32]

To reconcile general evolutionary theory with the origin of the human species, with a soul, the concept of "special transformism" was developed, according to which the first humans had evolved by Darwinist processes, up to the point where a soul was added by God to "pre-existent and living matter" (in the words of Pius XII's Humani generis) to form the first fully human individuals; this would normally be considered to be at the point of conception.[33] Léroy's book endorsed this concept; what led to its rejection by the Congregation appears to have been his view that the human species was able to evolve without divine intervention to a fully human state, but lacking only a soul. The theologians felt that some immediate and particular divine intervention was also required to form the physical nature of humans, before the addition of a soul, even if this was worked on near-human hominids produced by evolutionary processes.[34]

The following year, 1896, John Augustine Zahm, a well-known American Holy Cross priest who had been a professor of physics and chemistry at the Catholic University of Notre Dame, Indiana, and was then Procurator General of his Order in Rome, published Evolution and Dogma, arguing that Church teaching, the Bible, and evolution did not conflict.[35] The book was denounced to the Congregation of the Index, who decided to condemn the book but did not publish the corresponding decree, and consequently, the book was never included on the Index.[36] Zahm, who had returned to the United States as Provincial superior of his Order, wrote to his French and Italian editors in 1899, asking them to withdraw the book from the market; however, he never recanted his views.[37] In the meantime his book (in an Italian translation with the imprimatur of Siena[38]) had had a great impact on Geremia Bonomelli, the Bishop of Cremona in Italy, who added an appendix to a book of his own, summarizing and recommending Zahm's views. Bonomelli too was pressured, and retracted his views in a public letter, also in 1898.[39]

Zahm, like St. George Jackson Mivart and his followers, accepted evolution, but not the key Darwinist principle of natural selection, which was still a common position among biologists in general at the time. Another American Catholic author William Seton accepted natural selection also, and was a prolific advocate in the Catholic and general press.[40]

Pope Pius IX

[edit]

On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, during the papacy of Pope Pius IX, who defined dogmatically papal infallibility during the First Vatican Council in 1869–70. The council has a section on "Faith and Reason" that includes the following on science and faith:

9. Hence all faithful Christians are forbidden to defend as the legitimate conclusions of science those opinions which are known to be contrary to the doctrine of faith, particularly if they have been condemned by the Church; and furthermore they are absolutely bound to hold them to be errors which wear the deceptive appearance of truth. ... 10. Not only can faith and reason never be at odds with one another but they mutually support each other, for on the one hand right reason established the foundations of the faith and, illuminated by its light, develops the science of divine things; on the other hand, faith delivers reason from errors and protects it and furnishes it with knowledge of many kinds.

— Vatican Council I

On God the Creator, the First Vatican Council was very clear. The definitions preceding the "anathema" (as a technical term of Catholic theology, let him be "cut off" or excommunicated, cf. Galatians 1:6–9; Titus 3:10–11; Matthew 18:15–17) signify an infallible doctrine of the Catholic Faith (De Fide):

- On God the creator of all things

- If anyone denies the one true God, creator and lord of things visible and invisible: let him be anathema.

- If anyone is so bold as to assert that there exists nothing besides matter: let him be anathema.

- If anyone says that the substance or essence of God and that of all things are one and the same: let him be anathema.

- If anyone says that finite things, both corporal and spiritual, or at any rate, spiritual, emanated from the divine substance; or that the divine essence, by the manifestation and evolution of itself becomes all things or, finally, that God is a universal or indefinite being which by self-determination establishes the totality of things distinct in genera, species and individuals: let him be anathema.

- If anyone does not confess that the world and all things which are contained in it, both spiritual and material, were produced, according to their whole substance, out of nothing by God; or holds that God did not create by his will free from all necessity, but as necessarily as he necessarily loves himself; or denies that the world was created for the glory of God: let him be anathema.

According to Catholic theologian Dr. Ludwig Ott in his 1952 treatise Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma,[41] it is to be understood that these condemnations are of the errors of modern materialism (that matter is all there is), pantheism (that God and the universe are identical), and ancient pagan and gnostic-manichean dualism (where God is not responsible for the entire created world, since mere "matter" is evil not good, see Ott, page 79).

The First Vatican Council also upholds the ability of reason to know God from his creation:

1. The same Holy mother Church holds and teaches that God, the source and end of all things, can be known with certainty from the consideration of created things, by the natural power of human reason: ever since the creation of the world, his invisible nature has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made.

— Chapter 2, On Revelation; cf. Romans 1:19–20; and Wisdom chapter 13

Popes Leo XIII and Pius X

[edit]

Pope Leo XIII, who succeeded in 1878, was known to advocate a more open approach to science, but also to be frustrated by opposition to this within the Vatican and leading church circles, "lamenting on a number of occasions, and not in a particularly private way, the repressive attitudes to scholars exhibited by people around him, and among those he clearly included members of La Civiltà Cattolica college of writers". On one occasion there was "quite a scene when the Pope energetically refused to have the writings of Mons. D'Hulst of Paris put on the Index of Forbidden Books".[42]

Providentissimus Deus, "On the Study of Holy Scripture", was an encyclical issued by Leo XIII on 18 November 1893 on the interpretation of Scripture. It was intended to address the issues arising from both the "higher criticism" and new scientific theories, and their relation with Scripture. Nothing specific concerning evolution was said, and initially both those in favour and against evolution found things to encourage them in the text; however a more conservative interpretation came to be dominant, and the influence of the conservative Jesuit Cardinal Camillo Mazzella (with whom Leo had argued over Mons. D'Hulst) detected. Leo stressed the unstable and changing nature of scientific theory, and criticised the "thirst for novelty and the unrestrained freedom of thought" of the age, but accepted that the apparent literal sense of the Bible might not always be correct. In biblical interpretation, Catholic scholars should not "depart from the literal and obvious sense, except only where reason makes it untenable or necessity requires". Leo stressed that both theologians and scientists should confine themselves to their own disciplines as much as possible.[43]

An earlier encyclical of Leo's on marriage, Arcanum Divinae Sapientiae (1880), had described in passing the Genesis account of the creation of Eve from Adam's side as "what is to all known, and cannot be doubted by any."[44]

The Pontifical Biblical Commission issued a decree ratified by Pope Pius X on June 30, 1909, that stated that the literal historical meaning of the first chapters of Genesis could not be doubted in regard to "the creation of all things by God at the beginning of time; the special creation of man; the formation of the first woman from the first man; the unity of the human race". As in 1860, "special creation" was only referred to in respect of the human species.[45]

Pope Pius XII

[edit]Pope Pius XII's encyclical of 1950, Humani generis, was the first encyclical to specifically refer to evolution and took up a neutral position, again concentrating on human evolution:

The Church does not forbid that ... research and discussions, on the part of men experienced in both fields, take place with regard to the doctrine of evolution, in as far as it inquires into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter.[46]

Pope Pius XII's teaching can be summarized as follows:

- The question of the origin of man's body from pre-existing and living matter is a legitimate matter of inquiry for natural science. Catholics are free to form their own opinions, but they should do so cautiously; they should not confuse fact with conjecture, and they should respect the Church's right to define matters touching on Revelation.

- Catholics must believe, however, that humans have souls created immediately by God. Since the soul is a spiritual substance it is not brought into being through transformation of matter, but directly by God, whence the special uniqueness of each person.

- All men have descended from an individual, Adam, who has transmitted original sin to all mankind. Catholics may not, therefore, believe in "polygenism", the scientific hypothesis that mankind descended from a group of original humans (that there were many Adams and Eves).

Some theologians believe Pius XII explicitly excludes belief in polygenism as licit. Another interpretation might be this: As we have nowadays in fact models of thinking of how to reconcile polygenism with the original sin, it need not be condemned. The relevant sentence is this:

Now it is in no way apparent how such an opinion (polygenism) can be reconciled with that which the sources of revealed truth and the documents of the Teaching Authority of the Church propose with regard to original sin, which proceeds from a sin actually committed by an individual Adam and which, through generation, is passed on to all and is in everyone as his own.

— Pius XII, Humani generis, 37 and footnote refers to Romans 5:12–19; Council of Trent, Session V, Canons 1–4

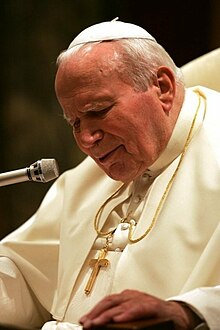

Pope John Paul II

[edit]

— John Paul II, 1996[47]

In an October 22, 1996, address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Pope John Paul II updated the Church's position to accept evolution of the human body:

In his encyclical Humani generis (1950), my predecessor Pius XII has already affirmed that there is no conflict between evolution and the doctrine of the faith regarding man and his vocation, provided that we do not lose sight of certain fixed points. ... Today, more than a half-century after the appearance of that encyclical, some new findings lead us toward the recognition of evolution as more than a hypothesis. In fact it is remarkable that this theory has had progressively greater influence on the spirit of researchers, following a series of discoveries in different scholarly disciplines. The convergence in the results of these independent studies—which was neither planned nor sought—constitutes in itself a significant argument in favor of the theory.[47]

In the same address, Pope John Paul II rejected any theory of evolution that provides a materialistic explanation for the human soul:

Theories of evolution which, because of the philosophies which inspire them, regard the spirit either as emerging from the forces of living matter, or as a simple epiphenomenon of that matter, are incompatible with the truth about man.

Pope Benedict XVI

[edit]Statements by Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, a close colleague of Benedict XVI, especially a piece in The New York Times on July 7, 2005,[48] appeared to support Intelligent Design, giving rise to speculation about a new direction in the Church's stance on the compatibility between evolution and Catholic doctrine; many of Schönborn's complaints about Darwinian evolution echoed pronouncements originating from the Discovery Institute, an interdenominational Christian think tank.[49][50] However, Cardinal Schönborn's book Chance or Purpose (2007, originally in German) accepted with certain qualifications the "scientific theory of evolution", but attacked "evolutionism as an ideology", which he said sought to displace religious teaching over a wide range of issues.[51] Nonetheless, in the mid-1980s, Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith Joseph Ratzinger wrote a defense of the doctrine of creation against Catholics who stressed the sufficiency of "selection and mutation."[52] Humans, Ratzinger writes, are "not the products of chance and error,"[52] and "the universe is not the product of darkness and unreason; it comes from intelligence, freedom, and from the beauty that is identical with love."[52]

The Church has deferred to scientists on matters such as the age of the earth and the authenticity of the fossil record. Papal pronouncements, along with commentaries by cardinals, have accepted the findings of scientists on the gradual appearance of life. In fact, the International Theological Commission in a July 2004 statement endorsed by Cardinal Ratzinger, then president of the Commission and head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, includes this paragraph:

According to the widely accepted scientific account, the universe erupted 15 billion years ago in an explosion called the 'Big Bang' and has been expanding and cooling ever since. Later there gradually emerged the conditions necessary for the formation of atoms, still later the condensation of galaxies and stars, and about 10 billion years later the formation of planets. In our own solar system and on earth (formed about 4.5 billion years ago), the conditions have been favorable to the emergence of life. While there is little consensus among scientists about how the origin of this first microscopic life is to be explained, there is general agreement among them that the first organism dwelt on this planet about 3.5–4 billion years ago. Since it has been demonstrated that all living organisms on earth are genetically related, it is virtually certain that all living organisms have descended from this first organism. Converging evidence from many studies in the physical and biological sciences furnishes mounting support for some theory of evolution to account for the development and diversification of life on earth, while controversy continues over the pace and mechanisms of evolution.[4]

The Church's stance is that any such gradual appearance must have been guided in some way by God, but the Church has thus far declined to define in what way that may be. Commentators tend to interpret the Church's position in the way most favorable to their own arguments. The ITC statement includes these paragraphs on evolution, the providence of God, and "intelligent design":

In freely willing to create and conserve the universe, God wills to activate and to sustain in act all those secondary causes whose activity contributes to the unfolding of the natural order which he intends to produce. Through the activity of natural causes, God causes to arise those conditions required for the emergence and support of living organisms, and, furthermore, for their reproduction and differentiation. Although there is scientific debate about the degree of purposiveness or design operative and empirically observable in these developments, they have de facto favored the emergence and flourishing of life. Catholic theologians can see in such reasoning support for the affirmation entailed by faith in divine creation and divine providence. In the providential design of creation, the triune God intended not only to make a place for human beings in the universe but also, and ultimately, to make room for them in his own trinitarian life. Furthermore, operating as real, though secondary causes, human beings contribute to the reshaping and transformation of the universe. A growing body of scientific critics of neo-Darwinism point to evidence of design (e.g., biological structures that exhibit specified complexity) that, in their view, cannot be explained in terms of a purely contingent process and that neo-Darwinians have ignored or misinterpreted. The nub of this currently lively disagreement involves scientific observation and generalization concerning whether the available data support inferences of design or chance, and cannot be settled by theology. But it is important to note that, according to the Catholic understanding of divine causality, true contingency in the created order is not incompatible with a purposeful divine providence. Divine causality and created causality radically differ in kind and not only in degree. Thus, even the outcome of a truly contingent natural process can nonetheless fall within God's providential plan for creation.[4]

In addition, while he was the Vatican's chief astronomer, Fr. George Coyne issued a statement on 18 November 2005 saying that "Intelligent design isn't science even though it pretends to be. If you want to teach it in schools, intelligent design should be taught when religion or cultural history is taught, not science." Cardinal Paul Poupard added that "the faithful have the obligation to listen to that which secular modern science has to offer, just as we ask that knowledge of the faith be taken in consideration as an expert voice in humanity." He also warned of the permanent lesson we have learned from the Galileo affair, and that "we also know the dangers of a religion that severs its links with reason and becomes prey to fundamentalism." Fiorenzo Facchini, professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Bologna, called intelligent design unscientific, and wrote in the January 16–17, 2006 edition L'Osservatore Romano: "But it is not correct from a methodological point of view to stray from the field of science while pretending to do science. ...It only creates confusion between the scientific plane and those that are philosophical or religious." Kenneth R. Miller is another prominent Catholic scientist widely known for opposing Young Earth Creationism and Intelligent Design. He writes, concerning Emeritus pope Benedict XVI, that "The Holy Father's concerns are not with evolution per se, but with how evolution is to be understood in our modern world. Biological evolution fits neatly into a traditional Catholic understanding of how contingent natural processes can be seen as part of God's plan ...a careful reading suggests that the new pope will give quarter neither to the enemies of spirituality nor the enemies of evolutionary science. And that's exactly as it should be."[53]

In a commentary on Genesis authored as Cardinal Ratzinger titled In the Beginning... Benedict XVI spoke of "the inner unity of creation and evolution and of faith and reason" and that these two realms of knowledge are complementary, not contradictory:

We cannot say: creation or evolution, inasmuch as these two things respond to two different realities. The story of the dust of the earth and the breath of God, which we just heard, does not in fact explain how human persons come to be but rather what they are. It explains their inmost origin and casts light on the project that they are. And, vice versa, the theory of evolution seeks to understand and describe biological developments. But in so doing it cannot explain where the 'project' of human persons comes from, nor their inner origin, nor their particular nature. To that extent we are faced here with two complementary—rather than mutually exclusive—realities.

— Cardinal Ratzinger, In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (Eerdmans, 1995), p. 50.

In a book released in 2008, his comments prior to becoming Pope were recorded as:

The clay became man at the moment in which a being for the first time was capable of forming, however dimly, the thought of "God". The first Thou that—however stammeringly—was said by human lips to God marks the moment in which the spirit arose in the world. Here the Rubicon of anthropogenesis was crossed. For it is not the use of weapons or fire, not new methods of cruelty or of useful activity, that constitute man, but rather his ability to be immediately in relation to God. This holds fast to the doctrine of the special creation of man ... herein ... lies the reason why the moment of anthropogenesis cannot possibly be determined by paleontology: anthropogenesis is the rise of the spirit, which cannot be excavated with a shovel. The theory of evolution does not invalidate the faith, nor does it corroborate it. But it does challenge the faith to understand itself more profoundly and thus to help man to understand himself and to become increasingly what he is: the being who is supposed to say Thou to God in eternity.

— Joseph Ratzinger[54]

On September 2–3, 2006 at Castel Gandolfo, Pope Benedict XVI conducted a seminar examining the theory of evolution and its impact on Catholicism's teaching of Creation. The seminar is the latest edition of the annual "Schülerkreis" or student circle, a meeting Benedict has held with his former Ph.D. students since the 1970s.[55][56] The essays presented by his former students, including natural scientists and theologians, were published in 2007 under the title Creation and Evolution (in German, Schöpfung und Evolution). In Pope Benedict's own contribution he states that "the question is not to either make a decision for a creationism that fundamentally excludes science, or for an evolutionary theory that covers over its own gaps and does not want to see the questions that reach beyond the methodological possibilities of natural science", and that "I find it important to underline that the theory of evolution implies questions that must be assigned to philosophy and which themselves lead beyond the realms of science."

In July 2007 at a meeting with clergy Pope Benedict XVI noted that the conflict between "creationism" and evolution (as a finding of science) is "absurd:" [57]

Currently, I see in Germany, but also in the United States, a somewhat fierce debate raging between so-called "creationism" and evolutionism, presented as though they were mutually exclusive alternatives: those who believe in the Creator would not be able to conceive of evolution, and those who instead support evolution would have to exclude God. This antithesis is absurd because, on the one hand, there are so many scientific proofs in favour of evolution which appears to be a reality we can see and which enriches our knowledge of life and being as such. But on the other, the doctrine of evolution does not answer every query, especially the great philosophical question: where does everything come from? And how did everything start which ultimately led to man? I believe this is of the utmost importance.

In commenting on statements by his predecessor, he writes "it is also true that the theory of evolution is not a complete, scientifically proven theory." Though commenting that experiments in a controlled environment were limited as "we cannot haul 10,000 generations into the laboratory", he does not endorse Young Earth Creationism or intelligent design. He defends theistic evolution, the reconciliation between science and religion already held by Catholics. In discussing evolution, he writes that "The process itself is rational despite the mistakes and confusion as it goes through a narrow corridor choosing a few positive mutations and using low probability.... This ... inevitably leads to a question that goes beyond science.... Where did this rationality come from?" to which he answers that it comes from the "creative reason" of God.[58][59][60]

The 150th anniversary of the publication of the Origin of Species saw two major conferences on evolution in Rome: a five-day plenary session of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in October/November 2008 on Scientific Insights Into the Evolution of the Universe and of Life[61] and another five-day conference on Biological Evolution: Facts and Theories, held in March 2009 at the Pontifical Gregorian University.[62] These meetings generally confirmed the lack of conflict between evolutionary theory and Catholic theology, and the rejection of Intelligent Design by Catholic scholars.[63]

On the evening of his death on December 31, 2022, the Holy See published the spiritual testament of Benedict XVI, which was witten on August 29, 2006. In regards to natural sciences, he wrote:[64]

What I said earlier of my compatriots, I now say to all who were entrusted to my service in the Church: Stand firm in the faith! Do not be confused! Often it seems as if science - on the one hand, the natural sciences; on the other, historical research (especially the exegesis of the Holy Scriptures) - has irrefutable insights to offer that are contrary to the Catholic faith. I have witnessed from times long past the changes in natural science and have seen how apparent certainties against the faith vanished, proving themselves not to be science but philosophical interpretations only apparently belonging to science - just as, moreover, it is in dialogue with the natural sciences that faith has learned to understand the limits of the scope of its affirmations and thus its own specificity.

Pope Francis

[edit]On October 27, 2014, Pope Francis issued a statement at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences that "Evolution in nature is not inconsistent with the notion of creation," warning against thinking of God's act of creation as "God [being] a magician, with a magic wand able to do everything."[65][66][67][68]

The Pope also expressed in the same statement the view that scientific explanations such as the Big Bang and evolution in fact require God's creation:

[God] created beings and allowed them to develop according to the internal laws that he gave to each one, so that they were able to develop and to arrive at their fullness of being. He gave autonomy to the beings of the universe at the same time at which he assured them of his continuous presence, giving being to every reality. And so creation continued for centuries and centuries, millennia and millennia, until it became what we know today, precisely because God is not a demiurge or a magician, but the creator who gives being to all things. ...The Big Bang, which nowadays is posited as the origin of the world, does not contradict the divine act of creating, but rather requires it. The evolution of nature does not contrast with the notion of creation, as evolution presupposes the creation of beings that evolve.[69]

"God is not... a magician, but the Creator who brought everything to life,” Francis said. “Evolution in nature is not inconsistent with the notion of creation, because evolution requires the creation of beings that evolve.”

Catholic teaching and evolution

[edit]The Catechism of the Catholic Church (1994, revised 1997) on faith, evolution and science states:

159. Faith and science: "... methodical research in all branches of knowledge, provided it is carried out in a truly scientific manner and does not override moral laws, can never conflict with the faith, because the things of the world and the things of faith derive from the same God. The humble and persevering investigator of the secrets of nature is being led, as it were, by the hand of God in spite of himself, for it is God, the conserver of all things, who made them what they are."[70]

283. The question about the origins of the world and of man has been the object of many scientific studies which have splendidly enriched our knowledge of the age and dimensions of the cosmos, the development of life-forms and the appearance of man. These discoveries invite us to even greater admiration for the greatness of the Creator, prompting us to give him thanks for all his works and for the understanding and wisdom he gives to scholars and researchers...[71]

284. The great interest accorded to these studies is strongly stimulated by a question of another order, which goes beyond the proper domain of the natural sciences. It is not only a question of knowing when and how the universe arose physically, or when man appeared, but rather of discovering the meaning of such an origin...[71]

Despite these general sections on scientific discussion of the origins of the world and of man, the Catechism does not explicitly discuss the theory of evolution in its treatment of human origins.[72] Paragraph 283 has been noted as making a positive comment regarding the theory of evolution, with the clarification that "many scientific studies" that have enriched knowledge of "the development of life-forms and the appearance of man" refers to mainstream science and not to "creation science".[73] [failed verification]

Concerning the doctrine on creation, Ludwig Ott in his Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma identifies the following points as essential beliefs of the Catholic faith ("De Fide"):[74]

- All that exists outside God was, in its whole substance, produced out of nothing by God.

- God was moved by His Goodness to create the world.

- The world was created for the Glorification of God.

- The Three Divine Persons are one single, common Principle of the Creation.

- God created the world free from exterior compulsion and inner necessity.

- God has created a good world.

- The world had a beginning in time.

- God alone created the world.

- God keeps all created things in existence.

- God, through His Providence, protects and guides all that He has created.

Some Catholic theologians, among them Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Piet Schoonenberg, and Karl Rahner, have discussed the problem of how evolutionary theory relates to the doctrine of original sin. They generally question the idea of a human fall from an original state of perfection and a common theme among them, most explicitly stated by Rahner, is to see Adam's sin as the sin of the entire human community, which provides a resolution of the problem of polygenism.[72]

Evolution in Catholic schools

[edit]The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2018) |

Catholic schools in the United States and other countries teach evolution as part of their science curriculum. They teach that evolution occurs and the modern evolutionary synthesis, which is the scientific theory that explains how evolution proceeds. This is the same evolution curriculum that secular schools teach. Bishop Francis X. DiLorenzo of Richmond, chair of the Committee on Science and Human Values, wrote in a letter sent to all U.S. bishops in December 2004: "Catholic schools should continue teaching evolution as a scientific theory backed by convincing evidence. At the same time, Catholic parents whose children are in public schools should ensure that their children are also receiving appropriate catechesis at home and in the parish on God as Creator. Students should be able to leave their biology classes, and their courses in religious instruction, with an integrated understanding of the means God chose to make us who we are."[75]

A survey of principals and teachers of science and of religion at Catholic high schools in the United States indicates some attitudes toward the teaching of evolution and the results of that teaching. 86% of principals reported their schools took an integrated approach to science and religion, in which "evolution, the Big Bang, and the Book of Genesis" were addressed together in classes. On specific topics, 95% of science teachers and 79% of religion teachers agreed that "evolution by natural selection" explains "the diversity of life on earth". Only 21% of science teachers and 32% of religion teachers believed that "Adam and Eve were real historical people". A companion survey of Catholic adults found that 65% of those who had attended a Catholic high school believed in evolution compared to 53% of those who did not attend.[76]

Unofficial Catholic organizations

[edit]There have been several organizations composed of Catholic laity and clergy which have advocated positions both supporting evolution and opposed to evolution, as well as individual figures such as Bruce Chapman. For example:

- The Kolbe Center for the Study of Creation operates out of Mt. Jackson, Virginia, and is a Catholic lay apostolate promoting creationism.[77]

- The "Faith Movement"[78] was founded by Catholic priests Fr. Edward Holloway and Fr. Roger Nesbitt in Surrey, England,[79] and "argues from Evolution as a fact, that the whole process would be impossible without the existence of the Supreme Mind we call God."[80]

- The Daylight Origins Society was founded in 1971 by John G. Campbell (d.1983) as the Counter Evolution Group. Its goal is "to inform Catholics and others of the scientific evidence supporting Special Creation as opposed to Evolution, and that the true discoveries of Science are in conformity with Catholic doctrines." It publishes the "Daylight" newsletter.[81]

- The Center for Science and Culture of the Discovery Institute was founded, in part, by Catholic biochemist Michael Behe, who is currently a senior fellow at the Center.[82][83]

Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., offers Catholics insight into the relation between Catholic faith and evolution theory. Despite occasional objections to aspects of his thought, Teilhard was never condemned by the magisterial church.[84][85][86]

The website "catholic.net", successor to the "Catholic Information Center on the Internet", sometimes features polemics against evolution.[87] Many "traditionalist" organizations are also opposed to evolution, see e.g. the theological journal Living Tradition (theological journal).[88]

See also

[edit]- Creation and evolution in public education

- Catholic Church and science

- Hindu views on evolution

- Islamic views on evolution

- Jainism and non-creationism

- Jewish views on evolution

- Relationship between religion and science

- Erich Wasmann

References

[edit]- ^ "What do Catholics believe about Adam and Eve? | Commonweal Magazine". www.commonwealmagazine.org. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^ "Adam and Eve Were Real People". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^ Richard P. McBrien (1995). The HarperCollins Encyclopædia of Catholicism. HarperCollins. p. 771. ISBN 9780006279310. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

From this most primitive form of life, the divinely-guided process of evolution by natural selection brought about higher life forms.

- ^ a b c International Theological Commission (July 2004) Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God, plenary sessions held in Rome 2000–2002, §63."Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God". Archived from the original on 2014-06-21. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- ^ Farrell, John (August 27, 2010). "Catholics and the Evolving Cosmos". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "Evolutionary Creation" (PDF). University of Alberta. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-04. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

Evolutionary creation best describes the official position of the Roman Catholic Church,[citation needed] though it is often referred to in this tradition as 'theistic evolution.'

- ^ Bill Bryson; A Short History of Nearly Everything; Black Swan; 2004; p.474

- ^ "Biography of Mendel at the Mendel Museum". Archived from the original on March 23, 2013.

- ^ Bill Bryson; A Short History of Nearly Everything; Black Swan; 2004; p.474-476

- ^ Bill Bryson; A Short History of Nearly Everything; Black Swan; 2004; p.300

- ^ "Nicholas Steno". ucmp.berkeley.edu.

- ^ O'Leary, 7–15; Harrison, section "The Defence: Fr. Domenichelli"; Brundell, 84

- ^ Harrison, especially Conclusion section 2

- ^ White, Andrew Dickson (1993). A history of the warfare of science with theology in Christendom (2 Volume Set). Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879758260.

- ^ "Catholic Education Resource Center".

- ^ "THE CONTEMPORARY RELEVANCE OF AUGUSTINE". www.asa3.org.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata Book VI, "For the creation of the world was concluded in six days" http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/02106.htm

- ^ Teske, Roland J. (1999). "Genesi ad litteram liber imperfectus, De". In Allan D. Fitzgerald (ed.). Augustine Through the Ages: An Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-8028-3843-8.

- ^ Hongzhen, Wang (1997). Comparative Planetology, Geological Education & History of Geosciences. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 262. ISBN 90-6764-254-1.

Uniformitarianism has dominated geological thinking since Lyell's time

- ^ Brundell, 86-87

- ^ Rafael Martinez, professor of the philosophy of science at the Santa Croce Pontifical University in Rome, in a speech reported on Catholic Ireland net Archived 2009-06-07 at the Wayback Machine Accessed May 26, 2009

- ^ 1948 Index listing Archived 2015-09-01 at the Wayback Machine—for some reason the date of publication is given as 1914 not 1907

- ^ The six leading examples are the subject of Artigas's book. Apart from Léroy, Zahm and Bonomelli, discussed below, there were St. George Jackson Mivart, the English Bishop John Hedley, and Raffaello Caverni. Each of these has a chapter in Artigas, and is also covered by Brundell.

- ^ Brundell, 81

- ^ The Vatican's View of Evolution: The Story of Two Popes Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine by Doug Linder (2004) citing H. L. Mencken on Religion by S. T. Joshi (2002), p. 163

- ^ Quoted in Harrison(2001)

- ^ Harrison(2001)

- ^ Artigas, 2,5,

- ^ Artigas, 2, 5, 7–9, 220 etc.; Brundell, 82-83, 90-92 etc.

- ^ John Henry Newman, Letter to J. Walker of Scarborough, May 22, 1868, The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973

- ^ Artigas, 119-120.

- ^ Harrison analyses the records at length.

- ^ Harrison, Conclusion section 4

- ^ Harrison, especially Conclusion sections.

- ^ Evolution and dogma By John Augustine Zahm Online text

- ^ Artigas, 124-202

- ^ The Zahn affair is the subject of Artigas's Chapter 4, and of Appleby's essay

- ^ Artigas, 209

- ^ Artigas, 209–216

- ^ Morrison, throughout

- ^ Grundriss der Katholischen Dogmatik (in German), Ludwig Ott, Verlag Herder, Freibury, 1952; First published in English as Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, Ludwig Ott, translated by Dr. Patrick Lynch and edited by James Canon Bastible, D.D.,The Mercier Press, Limited, May, 1955.

- ^ Brundell, 83-84, quoted in turn

- ^ O'Leary, 71

- ^ Arcanum Divinae Sapientiae Archived June 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Encyclical, Vatican website. Quotation from s.5. Cited by in Did women evolve from beasts, Harrison , Brian W. Living Tradition.

- ^ Evolution: A Catholic Perspective, James B. Stenson, Catholic Position Papers, Series A, Number 116, March, 1984, Japan Edition, Seido Foundation for the Advancement of Education, 12-6 Funado-Cho, Ashiya-Shi Japan.

- ^ Pius XII, encyclical Humani generis 36 Archived April 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b John Paul II, Message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences: On Evolution; the speech was made in French - for a dispute over whether the correct English translation of "la theorie de l'evolution plus qu'une hypothese" is "more than a hypothesis" or "more than one hypothesis", see Eugenie Scott, NCSE online version of Creationists and the Pope's Statement, which originally appeared in The Quarterly Review of Biology, 72.4, December 1997

- ^ Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, "Finding Design in Nature", published in The New York Times, July 7, 2005.

- ^ Matt Young; Taner Edis (2006). Why Intelligent Design Fails: A Scientific Critique of the New Creationism. Rutgers, The State University. ISBN 9780813538723. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

An influential Roman Catholic cardinal, Cristoph Schonborn, the archbishop of Vienna, appeared to retreat from John Paul II's support for evolution and wrote in The New York Times that descent with modification is a fact, but evolution in the sense of "an unguided, unplanned process of random variation and natural selection" is false. Many of Schonborn's complaints about Darwinian evolution echoed pronouncements originating from the Discovery Institute, the right-wing American think tank that plays a central role in the ID movement (and whose public relations firm submitted Schonborn's article to the Times).

- ^ Parliamentary Assembly, Working Papers: 2007 Ordinary Session. Council of Europe Publishing. 30 June 2008. ISBN 9789287163684. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

Christoph Schonborn, the Archbishop of Vienna, published an article in The New York Times stating that the declarations made by Pope John Paul II could not be interpreted as recognising evolution. At the same time, he repeated arguments put forward by the supporters of the intelligent design ideas.

- ^ Review by John F. McCarthy, Living Tradition. Quotes p. 150 of the English edition.

- ^ a b c Ronald L. Numbers (2006). The creationists: from scientific creationism to intelligent design. Random House. ISBN 9780674023390. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

Miffed by Krauss's comments, officers at the Discovery Institute arranged for the cardinal archbishop of Vienna, Cristoph Sconborn (b. 1945), to write an op-ed piece for the Times dismissing the late pope's statement as 'rather vague and unimportant' and denying the truth of 'evolution in the neo-Darwinian sense—an unguided, unplanned process of random variation and natural selection.' The cardinal, it seems, had received the backing of the new pope, Benedict XVI, the former Joseph Ratzinger (b. 1927), who in the mid-1980s, while serving as prefect of the Sacred Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, successor to the notorious Inquisition, had written a defense of the doctrine of creation against Catholics who stressed the sufficiency of 'selection and mutation.' Humans, he insisted, are 'not the products of chance and error,' and 'the universe is not the product of darkness and unreason. It comes from intelligence, freedom, and from the beauty that is identical with love.' Recent discoveries in microbiology and biochemistry, he was happy to say, had revealed 'reasonable design.'

- ^ "Kenneth R. Miller - Darwin's Pope? | Harvard Divinity Bulletin". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ^ Creation and Evolution: A Conference With Pope Benedict XVI in Castel Gandolfo, S.D.S. Stephan Horn (ed), pp. 15–16

- ^ Pope to Dissect Evolution With Former Students Archived 2006-08-16 at the Wayback Machine, Stacy Meichtry, Beliefnet

- ^ Benedict's Schulerkreis Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, John L. Allen Jr, National Catholic Reporter Blog, Sep 8, 2006

- ^ "Meeting Of The Holy Father Benedict XVI With The Clergy Of The Dioceses Of Belluno-Feltre And Treviso". Vatican.va. 2007-07-24. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- ^ Pope says science too narrow to explain creation, Tom Heneghan, San Diego Union-Tribune, April 11, 2007

- ^ Evolution not completely provable: Pope, Sydney Morning Herald, April 11, 2007

- ^ Pope praises science but stresses evolution not proven, USA Today, 4/12/2007

- ^ Arber, Werner; Cabibbo, Nicola; Sánchez Sorondo, Marcelo, eds. (2009), Scientific Insights Into the Evolution of the Universe and of Life, Pontificiae Academiae Scientiarum Acta, vol. 20, Vatican City: Ex Aedibus Academicis in Civitate Vaticana, ISBN 9788877610973

- ^ Auletta, Gennaro; LeClerc, Marc; Martinez, Rafael A., eds. (2011), Biological Evolution: Facts and Theories, Analecta Gregoriana, vol. 312, Rome: Gregorian & Biblical Press, ISBN 978-88-7839-180-2

- ^ Richard Owen: Vatican says Evolution does not prove the non-existence of God. In: The Times. March 6, 2009; accessed May 26, 2009 [dead link]

- ^ "Spiritual Testament of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI | BENEDICT XVI". www.vatican.va.

- ^ "Pope Says God Not 'A Magician, With A Magic Wand'". NPR.org. 28 October 2014.

- ^ "Pope says evolution doesn't mean there's no God". CNET. CBS Interactive. 27 October 2014.

- ^ Pope Francis backs theory of evolution, says God is no wizard, by Ishaan Tharoor, 28 October 2014

- ^ "Pope Francis: 'Evolution ... is not inconsistent with the notion of creation' - Religion News Service". Religion News Service. 27 October 2014.

- ^ "Francis inaugurates bust of Benedict, emphasizes unity of faith, science". cna. 27 October 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "Part One Section One I Believe - We Believe Chapter Three Man's Response To God Article 1 I Believe III. The Characteristics Of Faith". www.vatican.va.

- ^ a b "Part One Section Two I. The Creeds Chapter One I Believe in God the Father Article 1 I Believe in God the Father Almighty, Creator of Heaven and Earth Paragraph 4. The Creator".

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, James P. (2016), "Catholics Re-examining Original Sin in light of Evolutionary Science: The State of the Question", New Blackfriars, 99 (1083): 653–674, doi:10.1111/nbfr.12234, ISSN 1741-2005

- ^ Akin, Jimmy (January 2004). "Evolution and the Magisterium". This Rock. Archived from the original on 2007-08-04. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ^ Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma (originally published in 1952 in German), Ludwig Ott, these specific De Fide statements found in Ott on "The Divine Act of Creation", pages 79–91. The various Councils (Lateran IV, Vatican I, Florence, and others), the traditional statements of the Saints, Doctors, Fathers, and Scriptures are cited by Ott to document the Catholic dogma that God is ultimately the Creator of all things however he chose to do the creating (Genesis 1; Colossians 1:15ff; Hebrews 3; Psalm 19).

- ^ Guntzel, Jeff Severns (March 25, 2005), "Catholic schools steer clear of anti-evolution bias", National Catholic Reporter

- ^ Emurayeveya, Florence; Gray, Mark M. (Spring 2018), Science and Religion in Catholic High Schools (PDF) (CARA Special Report), Washington, DC: Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, retrieved 23 March 2018

- ^ Kolbe Center for the Study of Creation: Defending Genesis from a Traditional Catholic Perspective official website.

- ^ [1] official website.

- ^ Catholicism: a New Synthesis, Edward Holloway, 1969.

- ^ Theistic Evolution and the Mystery of FAITH (cont'd), Anthony Nevard, Theotokos Catholic Books website; Creation/Evolution Section.

- ^ Daylight Origins Society: Creation Science for Catholics official home page.

- ^ William A. Dembski (22 February 2006). Darwin's nemesis: Phillip Johnson and the intelligent design movement. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830828364. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

Michael J. Behe is professor of biological sciences at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania.... He is senior fellow with Discovery Institute's Center for Science and Culture.

- ^ Andrew J. Petto, Laurie R. Godfrey (2007). Scientists confront intelligent design and creationism. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393050905. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

Senior fellows at the CSC include mathematician David Berlinski, theological and molecular biologist Jonathan Wells, biophysicist Michael Behe, mathematician William Dembski, philosopher Paul Nelson, and others.

- ^ Warning Considering the Writings of Father Teilhard de Chardin Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, June 30, 1962.

- ^ Communiqué of the Press Office of the Holy See Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, English edition of L'Osservatore Romano, July 20, 1981.

- ^ Letter about Teilhard de Chardin Archived 2007-12-10 at the Wayback Machine, Etienne Gilson writing to Cardinal De Lubac, in Teilhard de Chardin: False Prophet, Dietrich von Hildebrand, Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1968.

- ^ "3". Archived from the original on 3 May 2008.

- ^ "Living Tradition - Journal of the Roman Theological Forum - Index of Back Issues". www.rtforum.org.

References

[edit]- Appleby, R. Scott. Between Americanism and Modernism; John Zahm and Theistic Evolution, in Critical Issues in American Religious History: A Reader, Ed. by Robert R. Mathisen, 2nd revised edn., Baylor University Press, 2006, ISBN 1-932792-39-2, ISBN 978-1-932792-39-3. Google books

- Artigas, Mariano; Glick, Thomas F., Martínez, Rafael A.; Negotiating Darwin: the Vatican confronts evolution, 1877–1902, JHU Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8018-8389-X, 9780801883897, Google books

- Brundell, Barry, "Catholic Church Politics and Evolution Theory, 1894-1902", The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Mar., 2001), pp. 81–95, Cambridge University Press on behalf of The British Society for the History of Science, JSTOR

- Harrison, Brian W., Early Vatican Responses to Evolutionist Theology, Living Tradition, Organ of the Roman Theological Forum, May 2001.

- Morrison, John L., "William Seton: A Catholic Darwinist", The Review of Politics, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Jul., 1959), pp. 566–584, Cambridge University Press for the University of Notre Dame du lac, JSTOR

- O'Leary, John. Roman Catholicism and modern science: a history, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 0-8264-1868-6, ISBN 978-0-8264-1868-5 Google books

- Scott, Eugenie C., "Antievolution and Creationism in the United States", Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 26, (1997), pp. 263–289, JSTOR

Further reading

[edit]- Bennett, Gaymon, Hess, Peter M. J. and others, The Evolution of Evil, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 3-525-56979-3, ISBN 978-3-525-56979-5, Google books

- Johnston, George (1998). Did Darwin Get It Right?. Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 0-87973-945-2. (google books)

- Hess, Peter M.J., Evolution, Suffering, and the God of Hope in Roman Catholic Thought after Darwin, in The Evolution of Evil (contains summary history of RC reaction; other pieces in the book are also relevant), 2008, Editors:Gaymon Bennett, Ted Peters, Martinez J. Hewlett, Robert John Russell; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 3525569793, 9783525569795, Google books

- Küng, Hans, The beginning of all things: science and religion, trans. John Bowden, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, ISBN 0-8028-0763-1, ISBN 978-0-8028-0763-2. Google books

- Olson, Richard, Science and religion, 1450–1900: from Copernicus to Darwin, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0-313-32694-0, ISBN 978-0-313-32694-3. Google books

- Rahner, Karl, ed. Encyclopedia of Theology: A Concise Sacramentum Mundi, entry on "Evolution", 1975, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0860120066, 9780860120063, google books

External links

[edit]- Vatican Council I (1869–70), the full documents.

- Evolutionary Creation: A Christian Approach to Evolution by Denis Lamoureux (St. Joseph's College, Edmonton)

- 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia: Catholics and Evolution and Evolution, History and Scientific Foundation of

- Pope Pius XII, Humani generis, 1950 encyclical

- Roberto Masi, "The Credo of Paul VI: Theology of Original Sin and the Scientific Theory of Evolution" (L'Osservatore Romano, 17 April 1969).

- Pope John Paul II, general audience of 10 July 1985. "Proofs for God's Existence are Many and Convergent".

- Cardinal Ratzinger's Commentary on Genesis Excerpts from In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall.

- International Theological Commission (2004). "Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God".

- Cardinal Paul Poupard, "Vatican Cardinal: Listen to What Modern Science has to Offer", November 3, 2005.

- Mark Brumley, "Evolution and the Pope, of Ignatius Insight Archived 2018-01-27 at the Wayback Machine

- John L. Allen Teaching of Benedict XVI on Evolution before becoming Pope.

- Benedict XVI's inaugural address.

- Pontifical Academy of Sciences