Argentines of European descent

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Argentinos Europeos (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

European Argentines in the inaugural parade of the Immigrant's Festival | |

| Total population | |

| 44,442,347 (2022 estimated)[1][2] 96.52% of the Argentina's population Full or parcial, including Mestizos, Highly inaccurate and speculative estimate | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| All areas of Argentina | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish • European languages (including Italian · Basque · German · Russian · English · Polish · Welsh · Galician · French · Yiddish · Ukrainian · Romani · Serbo-Croatian) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox) Minority Jewish • Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| European Americans · Spaniards · Italians · Germans · French · Irish · Portuguese · Poles · Romani · Croats · Ashkenazi · Others |

European Argentines (Spanish: Argentinos Europeos), are Argentines who have predominantly or total European ancestry (formerly called Criollos or Castizos in the viceregal era), belong to several communities which trace their origins to various migrations from Europe and which have contributed to the country's cultural and demographic variety.[3][4] They are the descendants of colonists from Spain during the colonial period prior to 1810,[5] or in the majority of cases, of Spanish, Italians, French, Russians and other Europeans who arrived in the great immigration wave from the mid 19th to the mid 20th centuries, and who largely intermarried among their many nationalities during and after this wave.[6] No recent Argentine census has included comprehensive questions on ethnicity, although numerous studies have determined that European Argentines have been a majority in the country since 1914.[7]

Distribution

[edit]European Argentinians may live in any part of the country, though their proportion varies according to region. Due to the fact that the main entry point for European immigrants was the Port of Buenos Aires, they settled mainly in the central-eastern region known as the Pampas (the provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Córdoba, Entre Ríos and La Pampa),[8] Their presence in the north-western region (mainly in the provinces of Jujuy and Salta) is less evident due to several reasons: it was the most densely populated region of the country (mainly by Amerindian and Mestizo people) until the immigratory wave of 1857 to 1940, and it was the area where the European newcomers settled the least.[8] During the last decades, due to internal migration from these north-western provinces and due to immigration especially from Bolivia, Perú and Paraguay (which have Amerindian and Mestizo majorities),[9][10][11] the percentage of European Argentines in certain areas of the Greater Buenos Aires has significantly decreased as well.[12]

Estimates

[edit]Neither official census data nor statistically significant studies exist on the precise amount or percentage of Argentines of European descent today. The Argentine government recognizes the different communities, but Argentina's National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) does not conduct ethnic/racial censuses, nor includes questions about ethnicity.[13][14] The Census conducted on 27 October 2010, did include questions on Indigenous peoples (complementing the survey performed in 2005) and on Afro-descendants.[13]

Genetic research

[edit]

It is estimated that more than 25 million Argentines (about 63%) have at least one Italian forefather.[15] Another study of the Amerindian ancestry of Argentines was headed by Argentine geneticist Daniel Corach of the University of Buenos Aires. The results of this study in which DNA from 320 individuals in 9 Argentine provinces was examined showed that 56% of these individuals had at least one Amerindian ancestor.[16] Another study on African ancestry was also conducted by the University of Buenos Aires in the city of La Plata. In this study 4.3% of the 500 study participants were shown to have some degree of African ancestry.[17] Nevertheless, it must be said here that this type of genetic studies -meant only to search for specific lineages in the mtDNA or in the Y-Chromosome, which do not recombine- may be misleading. For example, a person with seven European great-grandparents and only one Amerindian/Mestizo great-grandparent will be included in that 56%, although his/her phenotype will most probably be Caucasian.

A separate genetic study on genic admixture was conducted by Argentine and French scientists from multiple academic and scientific institutions (CONICET, UBA, Centre d'anthropologie de Toulouse). This study showed that the average contribution to Argentine ancestry was 79.9% European, 15.8% Amerindian and 4.3% African.[18] Another similar study was conducted in 2006, and its results were also similar. A team led by Michael F. Seldin from the University of California, with members of scientific institutes from Argentina, the United States, Sweden and Guatemala, analyzed samples from 94 individuals and concluded that the average genetic structure of the Argentine population contains a 78.1% European contribution, 19.4% Amerindian contribution and 2.5% African contribution (using the Bayesian algorithm).[19]

A team led by Daniel Corach conducted a new study in 2009, analyzing 246 samples from eight provinces and three different regions of the country. The results were as follows: the analysis of Y-Chromosome DNA revealed a 94.1% of European contribution (a little higher than the 90% of the 2005 study), and only 4.9% and 0.9% of Native American and Black African contribution, respectively. Mitochondrial DNA analysis again showed a great Amerindian contribution by maternal lineage, at 53.7%, with 44.3% of European contribution, and a 2% African contribution. The study of 24 autosomal markers also proved a large European contribution of 78.5%, against 17.3% of Amerindian and 4.2% Black African contributions. The samples were compared with three assumed parental populations, and the MDS analysis plot resulting showed that "most of the Argentinean samples clustered with or closest to Europeans, some appeared between Europeans and Native Americans indicating some degree of genetic admixture between these two groups, three samples clustered close to Native Americans, and no Argentinean sampled appeared close to Africans".[20][21]

- According to Caputo et al., 2021, the study of autosomal DIPs show that the genetic contribution is 77.8% European, 17.9% Amerindian and 4.2% African. The X-DIPs matrilineal show 52.9% European, 39.6% Amerindian, and 7.5% African.[22]

- Olivas et al., 2017, Nature: 84,1% European and 12,8% Amerindian.[23]

- Homburguer et al., 2015, PLOS One Genetics: 67% European, 28% Amerindian, 4% African and 1.4% Asian.[24]

- According to Seldin et al., 2006, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, the genetic structure of Argentina would be: 78.0% European, 19.4% Amerindian and 2.5% African. Using other methods it was found that it could be: 80.2% European, 18.1% Amerindian and 1.7% African.[25]

- In the work of Corach et al the authors say that "Argentineans carried a large fraction of European genetic heritage in their Y-chromosomal (94.1%) and autosomal (78.5%) DNA, but their mitochondrial gene pool is mostly of Native American ancestry (53.7%); instead, African heritage was small in all three genetic systems (<4%)".[26]

- Avena et al., 2012, PLOS One Genetics: 65% European, 31% Amerindian, and 4% African.[27]

- Buenos Aires Province: 76% European and 24% others.

- South Zone (Chubut Province): 54% European and 46% others.

- Northeast Zone (Misiones, Corrientes, Chaco & Formosa provinces): 54% European and 46% others.

- Northwest Zone (Salta Province): 33% European and 67% others.

- Other studies indicate that the genetic composition between regions would be:[28]

- Central Zone: 81% European, 15% Amerindian and 4% African

- South Zone: 68% European, 28% Amerindian and 4% African

- Northeast Zone: 79% European, 17% Amerindian and 4% African

- Northwest Zone: 55% European, 35% Amerindian and 10% African

- According to the study by María Laura Catelli et al, 2011. The Native American component observed in the urban populations was 66%, 41%, and 70% in South, Central, and North Argentina, respectively[29]

- Neide Maria de Oliveira Godinho, 2008, at the University of Brasília: 60% European, 31% Amerindian and 9% African.[30]

- National Geographic: 61% Caucasian (52% European + 9% Middle East/North Africa), 27% Amerindian ancestry and 9% African.[31]

- According to Norma Pérez Martín, 2007, at least 56% of Argentines would have indigenous ancestry.[32]

History

[edit]Colonial and post-independence period

[edit]The presence of European people in the Argentine territory began in 1516, when Spanish Conquistador Juan Díaz de Solís explored the Río de la Plata. In 1527, Sebastian Cabot founded the fort of Sancti Spiritus, near Coronda, Santa Fe; this was the first Spanish settlement on Argentine soil. The process of Spanish occupation continued with expeditions coming from Upper Peru (present-day Bolivia), that founded Santiago del Estero in 1553, San Miguel de Tucumán in 1565 and Córdoba in 1573, and from Chile, which founded Mendoza in 1561 and San Juan in 1562. Other Spanish expeditions founded the cities of Santa Fe (1573), Buenos Aires (1580), and Corrientes (1588).

* President Bernardino Rivadavia established the Immigration Commission.

* Jurist Juan Bautista Alberdi included the encouragement of European immigration in his draft for the Argentine Constitution.

It was not until the creation of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata in 1776, that the first censuses with classification into castas were conducted. The 1778 Census ordered by viceroy Juan José de Vértiz in Buenos Aires revealed that, of a total population of 37,130 inhabitants, the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 25,451, or 68.55% of the total. Another census carried out in the Corregimiento de Cuyo in 1777 showed that the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 4,491 (or 51.24%) out of a population of 8,765 inhabitants. In Córdoba (city and countryside) the Spanish/Criollo people comprised 39.36% (about 14,170) of 36,000 inhabitants.[33]

According to data from the Argentine government in 1810, about 6,000 Spanish lived in the territory of the United Provinces of Río de la Plata Spanish, of a total population of around 700,000 inhabitants.[34] This small number indicates that the presence of people with European ancestors was very small, and a large number of Criollos were mixed with indigenous and African mothers, although the fact was often hidden; in this regard, for example, according to researcher José Ignacio García Hamilton the Liberator, José de San Martín, would be mestizo.

Nevertheless, these censuses were generally restricted to the cities and the surrounding rural areas, so little is known about the racial composition of large areas of the Viceroyalty, though it is supposed that Spaniards and Criollos were always a minority, with the other castas comprising the majority.[5] It is worth noting that, since a person who was classified as Peninsular or Criollo had access to more privileges in the colonial society, many Castizos (resulting from the union of a Spanish and a mestizo) purchased their limpieza de sangre ("purity of blood").[33]

Although being a minority in demographics terms, the Criollo people played a leading role in the May Revolution of 1810, as well as in the independence of Argentina from the Spanish Empire in 1816. Argentine national heroes such as Manuel Belgrano and Juan Martín de Pueyrredón, military men as Cornelio Saavedra and Carlos María de Alvear, and politicians as Juan José Paso and Mariano Moreno were mostly Criollos of Spanish, Italian or French descent. The Second Triumvirate and the 1813 assembly enacted laws encouraging immigration, and instituted advertising campaigns and contract work programs among prospective immigrants in Europe.[35]

The Minister of Government of Buenos Aires Province, Bernardino Rivadavia, established the Immigration Commission in 1824. He appointed Ventura Arzac to conduct a new Census in the city, and it showed these results: the city had 55,416 inhabitants, of which 40,000 were of European descent (about 72.2%); of this total of Whites, a 90% were Criollos, a 5% were Spaniards, and the other 5% were from other European nations.[36]

After the wars for independence, a long period of internal struggle followed. During the period between 1826 and 1852, some Europeans settled in the country as well -sometimes hired by the local governments. Notable among them, Savoyan lithographer Charles Pellegrini (President Carlos Pellegrini's father) and his wife Maria Bevans, Neapolitan journalist Pedro de Angelis, and German physician/zoologist Hermann Burmeister. Because of this long conflict, there were neither economic resources nor political stability to carry out any census until the 1850s, when some provincial censuses were organized. These censuses did not continue the classification into castas typical of the pre-independence period.[37]

The administration of Governor Juan Manuel de Rosas, who had been given the sum of public power by other governors in the Argentine Confederation, maintained Rivadavia' Immigration Commission, which continued to advertise agricultural colonies in Argentina among prospective European immigrants.[35] Following Rosas' overthrow by Entre Ríos Province Governor Justo José de Urquiza, jurist and legal scholar Juan Bautista Alberdi was commissioned to prepare a draft for a new Constitution. His outline, Bases and Starting Points for the Political Organization of the Argentine Republic, called the Federal Government to "promote European immigration," and this policy would be included as Article 25 of the Argentine Constitution of 1853.[5]

The first post-independence census conducted in Buenos Aires took place in 1855; it showed that there were 26,149 European inhabitants in the city. Among the nationals there is no distinction of race, but it does distinguish literates from illiterates; at that time formal education was a privilege almost exclusive for the upper sectors of society, who were predominantly of European descent. Including European residents and the 21,253 Argentine literates, around 47,402 people of mainly European descent resided in Buenos Aires in 1855; they would have comprised about 51.6% of a total population of 91,895 inhabitants.[38]

Great wave of immigration from Europe (1857–1940)

[edit]* President Nicolás Avellaneda enacted Law 817 of Immigration and Colonization.

* President Julio Roca led the Conquest of the Desert in 1879, enabling Argentina to occupy new lands for the immigrants to buy and cultivate. Both Avellaneda and Roca belonged to traditional Criollo families from Tucumán.

In February 1856, the municipal government of Baradero granted lands for the settlement of ten Swiss families in an agricultural colony near that town. Later that year, another colony was founded by Swiss immigrants in Esperanza, Santa Fe. These provincial initiatives remained isolated cases until differences between the Argentine Confederation and the State of Buenos Aires were resolved with the Battle of Pavón in 1861, and a strong central government could be established. Presidents Bartolomé Mitre (the victor at Pavón), Domingo Sarmiento and Nicolás Avellaneda implemented policies that encouraged massive European immigration. These were formalized with the 1876 Congressional approval of Law 817 of Immigration and Colonization, signed by President Avellaneda. During the following decades, and until the mid-20th century, waves of European settlers came to Argentina. Major contributors included Italy (initially from Piedmont, Veneto and Lombardy, later from Campania, Calabria, and Sicily),[39] and Spain (most were Galicians and Basques, but there were Asturians).[40]

Smaller but significant numbers of immigrants include those from France, Poland, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Croatia, England, Scotland, Ireland, Switzerland, Belgium, Denmark, and others. Europeans from the former Ottoman Empire were mainly Greek.[citation needed] The majority of Argentina's Jewish community descend from immigrants of Ashkenazi Jewish origin.[41]

- This migratory influx had mainly two effects on Argentina's demography

1) The exponential growth of the country's population. In the first National Census of 1869 the Argentine population was just 1,877,490 inhabitants, in 1895 it had doubled to 4,044,911, in 1914 it had reached 7,903,662, and by 1947 it had doubled again to 15,893,811. It is estimated that by 1920, more than 50% of the residents in Buenos Aires had been born abroad. According to Zulma Recchini de Lattes' estimate, if this great immigratory wave from Europe and the Middle East had not happened, Argentina's population by 1960 would have been less than 8 million, while the national census carried out that year revealed a population of 20,013,793 inhabitants.[42] Argentina received a total of 6,611,000 European and Middle-Eastern immigrants during the period 1857–1940; 2,970,000 were Italians (44.9%), 2,080,000 were Spaniards (31.5%), and the remaining 23.6% was composed of French, Poles, Russians, Germans, Austro-Hungarians, British, Portuguese, Swiss, Belgians, Danes, Dutch, Swedes, etc.[40]

2) A radical change in its ethnic composition; the 1914 National Census revealed that around 80% of the national population were either European immigrants, their children or grandchildren.[43] Among the remaining 20% (those descended from the population residing locally before this immigrant wave took shape), around a fifth were of mainly European descent. Put down to numbers, this means that about 84%, or 6,300,000 people (out of a total population of 7,903,662), residing in Argentina were of European descent.[5] European immigration continued to account for over half the nation's population growth during the 1920s, and was again significant (albeit in a smaller wave) following World War II.[43]

The distribution of these European/Middle Eastern immigrants was not uniform across the country. Most newcomers settled in the coastal cities and the farmlands of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Córdoba and Entre Ríos. For example, the 1914 National Census showed that, of almost three million people −2,965,805 to be exact- living in the provinces of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe, 1,019,872 were European immigrants, and one and a half million more were children of European mothers; in all, this community comprised at least 84.9% of this region's population. The same dynamic was less evident in the rural areas of the northwestern provinces, however: immigrants (mostly of Syrian-Lebanese origin) represented a mere 2.6% (about 15,600) of a total rural population of 600,000 in Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Santiago del Estero and Catamarca.[8][44]

Origin of the immigrants between 1857 and 1920

[edit]| Net Immigration by Nationality (1857–1920)[45] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Subjecthood or Citizenship | Total numbers of immigrants | Percentage of total |

| 2,341,126 | 44.72% | |

| 1,602,752 | 30.61% | |

| 221,074 | 4.22% | |

| 163,862 | 3.13% | |

| 141,622 | 2.71% | |

| 87,266 | 1.67% | |

| 69,896 | 1.34% | |

| 60,477 | 1.16% | |

| 34,525 | 0.66% | |

| 30,729 | 0.59% | |

| 23,549 | 0.45% | |

| 10,644 | 0.20% | |

| 8,111 | 0.15% | |

| 8,067 | 0.15% | |

| 2,223 | 0.04% | |

| 1,000 | 0.02% | |

| Others | 428,471 | 8.18% |

| Total | 5,235,394[47] | |

Notes:

- (1) This figure includes Russians, Ukrainians, Volga Germans, Belarusians, Poles, Lithuanians, etc. that entered Argentina with passport of the Russian Empire.

- (2) This figure includes all the peoples that lived within the boundaries of the Austro-Hungarian Empire between 1867 and 1918: Austrians, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenians, Croatians, Bosniaks, Ruthenians and people from the regions of Vojvodina in Serbia, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol and Trieste in Italy, Transylvania in Romania, and Galicia in Poland.

- (3) The United Kingdom included Ireland until 1922; that is why most of the British immigrants -nicknamed "ingleses"- were in fact Irish, Welsh and Scottish.

- (4) Around 0.5% of Luxembourg's total population emigrated to Argentina during the 1880s.

Source: Dirección Nacional de Migraciones: Infografías., that information was modified – figures there are by nationality, not by country.

Origin of the immigrants between 1857 and 1940

[edit]| Immigration by Nationality (1857–1940) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Subjecthood or Citizenship | Total numbers of immigrants | Percentage of total |

| 2,970,000 | 36.7% | |

| 2,080,000 | 25.7% | |

| 239,000 | 2.9% | |

| 180,000 | 2.2% | |

| 177,000 | 2.2% | |

| 174,000 | 2.1% | |

| 111,000 | 1.4% | |

| 75,000 | 1.0% | |

| 72,000 | 0.9% | |

| 65,000 | 0.8% | |

| 48,000 | 0.6% | |

| 44,000 | 0.6% | |

| 26,000 | 0.3% | |

| 18,000 | 0.2% | |

| 12,000 | 0.2% | |

| 10,000 | 0.2% | |

| 7,000 | 0.1% | |

| Others | 223,000 | 2.8% |

| Total[Note 1] | 6,611,000 | 100.0% |

Source: National Migration, 1970.[citation needed]

- ^ About 52% of immigrants in the period 1857–1939 were definitively settled.

Second wave of immigration

[edit]* Kay Galiffi, guitarist of rock band Los Gatos. He was born in Italy in 1948; his parents emigrated with him to Rosario, Santa Fe in 1950.

During and after the Second World War, many Europeans fled to Argentina, escaping the hunger and poverty of the post-war period. According to the National Bureau of Migrations, during the period 1941–1950 at least 392,603 Europeans entered the country: 252,045 Italians, 110,899 Spaniards, 16,784 Poles, 7,373 Russians and 5,538 French.[57] Among the notable Italian immigrants in that period were protest singer Piero De Benedictis (emigrated with his parents in 1948),[58] actors Rodolfo Ranni (emigrated in 1947)[59] and Gianni Lunadei (1950),[60] publisher César Civita (1941),[61] businessman Francisco Macri (1949),[62] lawmaker Pablo Verani (1947),[63] and rock musician Kay Galiffi (1950).[64]

Argentina also received thousands of Germans, including the humanitarian businessman Oskar Schindler and his wife, hundreds of Ashkenazi Jews, and hundreds of Nazi war criminals. Notorious beneficiaries of ratlines included Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, Erich Priebke, Rodolfo Freude (who became the first director of Argentine State Intelligence), and the Ustaše Head of State of Croatia, Ante Pavelić. It is still matter of debate whether the Argentine government of President Juan Perón was aware of the presence of these criminals on Argentine soil or not; but the consequence was that Argentina was considered a Nazi haven for several decades.[65]

The flow of European immigration continued during the 1950s and afterward; but compared to the previous decade, it diminished considerably.[43] The Marshall Plan implemented by the United States to help Europe recover from the consequences of World War II was working, and emigration lessened. During the period 1951–1960, only 242,889 Europeans entered Argentina: 142,829 were Italians, 98,801 were Spaniards, 934 were French, and 325 were Poles. The next decade (1961–1970), the total number of European immigrants barely reached 13,363 (9,514 Spaniards, 1,845 Poles, 1,266 French and 738 Russians).[57]

European immigration was nearly non-existent during the 1970s and the 1980s. Instability from 1970 to 1976 in the form of escalating violence between Montoneros and the Triple A, guerrilla warfare, and the Dirty War waged against leftists after the March 1976 coup, was compounded by an economic crisis caused by the 1981 collapse of the dictatorship's domestic policies. This situation encouraged emigration rather than immigration of Europeans and European-Argentines alike, and during the 1971–1976 period at least 9,971 Europeans left the country.[57] During the period 1976–1983 thousands of Argentines and numerous Europeans were kidnapped and killed in clandestine centers by the military dictatorship's grupos de tareas (task groups); these included Haroldo Conti, Dagmar Hagelin, Rodolfo Walsh, Léonie Duquet, Alice Domon, Héctor Oesterheld (all presumably assassinated in 1977) and Jacobo Timerman (who was liberated in 1979; sought exile in Israel, and returned in 1984). CONADEP, the commission formed by President Raúl Alfonsín, investigated and documented the existence of at least 8,960 cases,[68] though other estimates vary between 13,000 and 30,000 dead.

Recent trends

[edit]The principal source of immigration into Argentina after 1960 was no longer from Europe, but rather from bordering South American countries. During the period in between the Censuses of 1895 and 1914, immigrants from Europe comprised 88.4% of the total, and Latin American immigrants represented only 7.5%. By the 1960s, however, this trend had been completely reversed: the Latin American immigrants were 76.1%, and the Europeans merely 18.7% of the total.[69]

Given that the main sources of South American immigrants since the 1960s have been Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru, most of these immigrants have been either Amerindian or Mestizo, for they represent the ethnic majorities in those countries.[9][10][11] The increasing numbers of immigrants from these sources has caused the proportion of Argentines of European descent to be reduced significantly in certain areas of the Greater Buenos Aires (particularly in Morón, La Matanza, Escobar and Tres de Febrero), as well as the Buenos Aires neighbourhoods of Flores, Villa Soldati, Villa Lugano and Nueva Pompeya.[12] Many Amerindian or Mestizo people of Bolivian/Paraguayan/Peruvian origin have suffered racist discrimination, and in some cases, violence,[70][71] or have been victims of sexual slavery[72] and forced labor in textile sweat shops.[73]

Latin American immigrants of European origin

[edit]Latin Americans of predominantly European descent have arrived from countries where there is a relevant proportion of white population Chile (52.7%[74] to 68%[75]), Brazil (47.7%[76][77]), Venezuela (43.6%[78]), Colombia (20%[74] to 37%[79]), Paraguay (20%[74] to 30%[80]) and in particular, Uruguay (88%[81] to 94%[82]). Uruguayan immigrants represent a very distinct case in Argentina, for they may pass unnoticed as "foreigners". Uruguay received a great part of the same influx of European immigrants that changed Argentina's ethnic profile, so most Uruguayans are of European origin. Uruguayans and Argentines also speak the same Spanish dialect (Rioplatense Spanish), which is heavily influenced by the intonation patterns of the Italian language's southern dialects.[83]

The official censuses show a slow growth in the Uruguayan-born community: 51,100 in 1970, 114,108 in 1980, and 135,406 in 1991, with a decline to 117,564 in 2001.[84] Around 218,000 Uruguayans emigrated to Argentina between 1960 and 1980, however.[85]

Third immigratory wave from Eastern Europe (1994–2000)

[edit]Following the fall of the Communist regimes of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the governments of the Western Bloc were worried about a possible massive exodus from Eastern Europe and Russia. President Carlos Saúl Menem – in the political framework of the Washington Consensus – offered to receive part of that emigratory wave in Argentina. Accordingly, Resolution 4632/94 was enacted on 19 December 1994, allowing "special treatment" for all the applicants who wished to emigrate from the former Soviet republics. A total of 9,399 Eastern Europeans emigrated to Argentina from January 1994 to December 2000, and of the total, 6,720 were Ukrainians (71.5%), 1,598 were Russians (17%), 160 Romanians (1.7%), 122 Bulgarians (1.3%), 94 Armenians (1%), 150 Georgians/Moldovans/Poles (1.6%) and 555 (5.9%) traveled with a Soviet passport.[86]

Around 85% of the newcomers were under age 45, and 51% had a university education, so most integrated quite rapidly into Argentine society, albeit with some initial difficulties finding gainful employment.[87] These also included some 200 Romanian Gypsy families that arrived in 1998, and 140 more Romanian Gypsies who migrated to Uruguay in 1999, but only to enter Argentina later by crossing the Uruguay river through Fray Bentos, Salto or Colonia.[88]

European immigration in Argentina has not stopped since this wave from Eastern Europe. According to the National Bureau of Migrations, some 14,964 Europeans have settled in Argentina (3,599 Spaniards, 1,407 Italians and 9,958 from other countries) during the period 1999–2004. To this figure, many of the 8,285 Americans and 4,453 Uruguayans may be added,[original research?] since these countries have European-descended majorities of 75%[89] and 87%[90] in their populations.[6]

Influences on Argentine culture

[edit]The culture of Argentina is the result of a fusion of European, Amerindian, Black African, and Arabic elements. The impact of European immigration on both Argentina's culture and demography has largely become mainstream and is shared by most Argentines, being no longer perceived as a separate "European" culture. Even those traditional elements that have Amerindian origin – as the mate and the Andean music – or Criollo origin – the asado, the empanadas, and some genres within folklore music – were rapidly adopted, assimilated and sometimes modified by the European immigrants and their descendants.[43][91][92]

Tango

[edit]

* Ástor Piazzolla (1921–1992) was the creator of "New Tango" and one of the finest bandoneonists ever; his parents were Italian immigrants from Trani, Apulia.[97]

Argentine tango is a hybrid genre, result of the fusion of different ethnic and cultural elements, so well intermingled that it is difficult to identify them separately. According to some experts, tango has combined elements from three main sources:

1) The music played by the Black African communities of the Río de la Plata region. Its very name might derive from a word in Yoruba -a Bantu language- and its rhythm appears to be based on candombe.[98]

2) The milonga campera, a popular genre among the gauchos that lived in the Buenos Aires countryside, and later moved to the city looking for better jobs.

3) The music brought by the European immigrants: the Andalucian tanguillo, the polka, the waltz and the tarantella.[99] They heavily influenced its melody and its sound by adding instruments such as piano, violin and -especially- bandoneón.

In spite of this tripartite origin, tango mainly developed as urban music, and was assimilated and embraced by European immigrants and their descendants; most icons of the genre were either European or had largely European ancestry.[100]

Argentine Folk music

[edit]When the Spaniards arrived in what is now Argentina, the Amerindian inhabitants already had their own musical culture: instruments, dances, rhythms and styles. Much of that culture was lost during and after the conquest; only the music played by the Andean peoples survived in the shape of chants such as vidalas and huaynos, and in dances like the carnavalito. The peoples of Gran Chaco and Patagonia -areas that the Spaniards did not effectively occupied- kept their cultures almost untouched until the late 19th century.[43]

The major Spanish contribution to music in the Río de la Plata area during the colonial period was the introduction of three instruments: the vihuela or guitarra criolla, the bombo legüero[citation needed] and the charango (a small guitar, similar to the tiple used in the Canary Islands; made with the shell of an armadillo). Once the Criollos obtained their independence from Spain, they had the chance to create new musical styles; dances like pericón, triunfo, gato and escondido, and chants such as cielito and vidalita all appeared during the post-independence period, primarily in the 1820s.[102]

European immigration brought important changes to Argentina's popular music, especially in the Litoral; where new genres appeared, like chamamé and purajhei (or Paraguayan polka). Chamamé appeared in the second half of the 18th century -though it was not named as such until the 1930s- as a result of the fusion of ancient Guaraní rhythms with the music brought by the Volga German, Ukrainian, Polish and Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants that settled in the region. The newcomers added the melodic style of their polkas and waltzes to the native rhythmic base, and played it with their own instruments, such as accordions and violins.

Other genres -like chacarera and zamba- developed as an integral fusion of Amerindian and European influences. While traditionally played on guitars, charangos and bombos, they also began to be played with other European instruments, such as piano; one notable example is Sixto Palavecino's use of the violin to play the chacarera. Regardless of the origin of the different rhythms and styles, later European immigrants and their descendants rapidly assimilated the local music and contributed to those genres creating new songs.

Sports

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) |

Many sports that nowadays are very popular in Argentina were introduced by European immigrants -particularly by the British- in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Football is by far the most popular sport in Argentina. It was brought by the British railway businessmen and workers, and it was later embraced with passion by the other collectivities. The first official football match ever played in Argentina took place on 20 June 1867, when the "White Caps" beat the "Red Caps" by 4–0. A look at the list of players -eight by team- shows a collection of British names/surnames. "White Caps": Thomas Hogg, James Hogg, Thomas Smith, William Forrester, James W. Bond, E. Smith, Norman Smith and James Ramsbotham. "Red Caps": Walter Heald, Herbert Barge, Thomas Best, Urban Smith, John Wilmott, R. Ramsay, J. Simpson and William Boschetti.[104] The development of this sport in Argentina was greatly boosted by Scottish teacher Alexander Watson Hutton. He arrived in Argentina in 1882 and founded the Buenos Aires English High School in 1884, hiring his countryman William Walters as coach of the school's football team. On 21 February 1893 Watson founded the Argentine Association Football League, the historical antecedent of the Asociación de Fútbol Argentino.[105][106] Watson's son Arnold continued the tradition playing during the amateur age of Argentine football.

Tennis was also imported by the British immigrants; in April 1892 they founded the Buenos Aires Lawn Tennis Club. Among the founding members, we find all British surnames: Arthur Herbert, W. Watson, Adrian Penard, C. Thursby, H. Mills and F. Wallace. Soon their example was followed by British immigrants who resided in Rosario; F. Still, T. Knox, W. Birschoyle, M. Leywe and J. Boyles founded the Rosario Lawn Tennis.[106]

The first Argentine tennis player of European descent to achieve some international success was Mary Terán de Weiss in the 1940s and 1950s; the sport, however, was considered an elite men's sport and her efforts to popularize this activity among women did not prosper at the time.[108] Guillermo Vilas, who is of Spanish descent,[109] won the French Open and the US Open both in 1977, and two Australian Open in 1978 and 1979, and popularized the sport in Argentina.

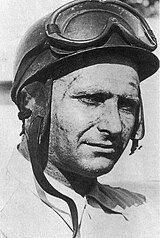

Another sport in which Argentines with European ancestry have stood out is car racing. The greatest exponent was Juan Manuel Fangio, whose parents were both Italian.[110] He won five Formula One World titles in 1951, 1954, 1955, 1956 and 1957; his five-championships record remained unbeaten until 2003, when Michael Schumacher obtained his sixth F1 trophy. Another exponents are Carlos Alberto Reutemann (his grandfather was German Swiss, and his mother was Italian), who reached the second place in the World Drivers' Championship of 1981.

Boxing is another popular sport which was also brought by the British immigrants. The first championship ever organized in Argentina took place in December 1899, and the champion was Jorge Newbery (son of a White American odontologist who migrated after the American Civil War), one of the pioneers of boxing, car racing and aviation in the country.[112] A list of Argentine boxers of European descent should include: Luis Ángel Firpo (nicknamed "the wild bull of the pampas", whose father was Italian and his mother was Spanish[113]), Nicolino Locche (who was nicknamed "the Untouchable" for his defensive style; both his parents were Italian[114][111]), etc.

Golf was brought to Argentina by Scottish Argentine Valentín Scroggie, who established the nation's first golf course in San Martín, Buenos Aires in 1892.[108] The Argentine Golf Association was founded in 1926 and includes over 43,000 members.[115]

Hockey was another sport imported by the British immigrants in the early 20th century. It was initially played in the clubs founded by the British citizens until 1908, when the first official matches between Belgrano Athletic, San Isidro Club y Pacific Railways (today San Martín) took place. That same year the Asociación Argentina de Hockey was founded, and its first president was Thomas Bell. In 1909 this Association allowed the formation of female teams. One of the first feminine teams was Belgrano Ladies; they played their first match on 25 August 1909, against St. Catherine's College, winning by 1 to 0.[116]

Cycling was introduced by Italian immigrants in Argentina in 1898, when they founded the Club Ciclista Italiano. One of the first South American champions in this sport was an Argentine of Italian descent, Clodomiro Cortoni.[117]

Rugby was also brought by British immigrants. The first rugby match ever played in Argentina took place in 1873; the teams were Bancos (Banks) against Ciudad (City). In 1886, the Buenos Aires Football Club and Rosario Athletic Club played the first official match between clubs. The River Plate Rugby Championship was founded on 10 April 1889, and was the direct antecedent of the Unión Argentina de Rugby, created to organize local championships; the founding clubs were Belgrano Athletic, Buenos Aires Football Club, Lomas Athletic and Rosario Athletic. Its first president was Leslie Corry Smith, and Lomas Athletic was the first champion that same year.[108]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Censo 2022". INDEC. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ According to the 2022 Census, it is estimated that 96.52% of Argentines have European or Asian ancestry, including mestizos and mulattos. However, there are no official census data or statistically significant studies on the precise number or percentage of Argentines of European ancestry today, because Argentina only conducts censuses of Indigenous and Black people.

- ^ Todd L. Edwards (2008). Argentina: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 192–194. ISBN 978-1-85109-986-3. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Sociología Argentina. by José Ingenieros. Editorial Losada, 1946. Pages 453, 469, 470.

- ^ a b c d Historical Dictionary of Argentina. London: Scarecrow Press, 1978. pp. 239–40.

- ^ a b "Acerca de la Argentina: Inmigración" [About Argentina: Immigration]. Government of Argentina (in Spanish). 2005. Archived from the original on 13 March 2008.

- ^ Francisco Lizcano Fernández (31 May 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of the Three Cultural Areas of the American Continent to the Beginning of the 21st century] (PDF). Convergencia (in Spanish) (38). México: 185–232. ISSN 1405-1435. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Oscar Chamosa (February 2008). "Indigenous or Criollo: The Myth of White Argentina in Tucumán's Calchaquí Valley" (PDF). Hispanic American Historical Review. 88 (1). Duke University Press: 77–79. doi:10.1215/00182168-2007-079.

- ^ a b Ben Cahoon. "Bolivia". World Statesmen.org. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b Ben Cahoon. "Perú". World Statesmen.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b Ben Cahoon. "Paraguay". World Statesmen.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Bolivianos en la Argentina" [Bolivians in Argentina]. Edant.clarin.com (in Spanish). 22 January 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b INDEC, 2010 National Census. (Spanish) See temas nuevos.

- ^ "Acerca de la Argentina: Colectividades" [About Argentina: Communities]. Government of Argentina (in Spanish). 2005. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010.

- ^ Departamento de Derecho y Ciencias Políticas de la Universidad Nacional de La Matanza (14 November 2011). "Historias de inmigrantes italianos en Argentina" (in Spanish). infouniversidades.siu.edu.ar.

Se estima que en la actualidad, el 90% de la población argentina tiene alguna ascendencia europea y que al menos 25 millones están relacionados con algún inmigrante de Italia.

- ^ "Estructura genética de la Argentina, Impacto de contribuciones genéticas – Ministerio de Educación de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Nación. (Spanish)". Coleccion.educ.ar. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Almost two million Argentinians have roots in Subsaharan Africa. (Spanish) by Patricio Downes. Clarín 9 June 2006.

- ^ Mezcla génica en una muestra poblacional de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Avena, Sergio A., Goicochea, Alicia S., Rey, Jorge et al. (2006). Medicina (Buenos Aires), mar./abr. 2006, vol.66, no.2, pp. 113–118. ISSN 0025-7680 (in Spanish)

- ^ "Argentine population genetic structure: Large variance in Amerindian contribution" by Michael F. Seldin, et al (2006). American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Volume 132, Issue 3, Pages 455–462. Published Online: 18 December 2006.

- ^ Corach, Daniel (2010). "Inferring Continental Ancestry of Argentineans from Autosomal, Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial DNA". Annals of Human Genetics. 74 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00556.x. hdl:11336/14301. PMID 20059473. S2CID 5908692.

- ^ How Argentina Became White. Magazine Discover: Science, Technology and the Future.

- ^ Caputo, M.; Amador, M. A.; Sala, A.; Riveiro Dos Santos, A.; Santos, S.; Corach, D. (2021). "Ancestral genetic legacy of the extant population of Argentina as predicted by autosomal and X-chromosomal DIPs". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 296 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1007/s00438-020-01755-w. PMID 33580820. S2CID 231911367. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Olivas; et al. (2017). "Variable frequency of LRRK2 variants in the Latin American research consortium on the genetics of Parkinson's disease (LARGE-PD), a case of ancestry". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41531-017-0020-6. PMC 5460260. PMID 28649619.

- ^ Homburger; et al. (2015). "Genomic Insights into the Ancestry and Demographic History of South America". PLOS Genetics. 11 (12): e1005602. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005602. PMC 4670080. PMID 26636962.

- ^ Seldin; et al. (2006). "Argentine Population Genetic Structure: Large Variance in Amerindian Contribution". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (3): 455-462. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20534. PMC 3142769. PMID 17177183.

- ^ Corach, Daniel; Lao, Oscar; Bobillo, Cecilia; Van Der Gaag, Kristiaan; Zuniga, Sofia; Vermeulen, Mark; Van Duijn, Kate; Goedbloed, Miriam; Vallone, Peter M.; Parson, Walther; De Knijff, Peter; Kayser, Manfred (15 December 2009). "Inferring Continental Ancestry of Argentineans from Autosomal, Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial DNA". Annals of Human Genetics. 74 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00556.x. hdl:11336/14301. PMID 20059473. S2CID 5908692.

- ^ Avena; et al. (2012). "Heterogeneity in Genetic Admixture across Different Regions of Argentina". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e34695. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734695A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034695. PMC 3323559. PMID 22506044.

- ^ Salzano, F. M.; Sans, M. (2013). "Interethnic admixture and the evolution of Latin American populations". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 37 (1 Suppl): 151–170. doi:10.1590/s1415-47572014000200003. PMC 3983580. PMID 24764751.

- ^ Catelli, María; Álvarez-Iglesias, Vanesa; Gómez-Carballa, Alberto; Mosquera-Miguel, Ana; Romanini, Carola; Borosky, Alicia; Amigo, Jorge; Carracedo, Ángel; Vullo, Carlos; Salas, Antonio (2011). "The impact of modern migrations on present-day multi-ethnic Argentina as recorded on the mitochondrial DNA genome". BMC Genetics. 12: 77. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-12-77. PMC 3176197. PMID 21878127.

- ^ de Oliveira Godinho, Neide Maria (2008). O impacto das migrações na constituição genética de populações latino-americanas (DSc thesis) (in Brazilian Portuguese). University of Brasília. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Reference Populations - Geno 2.0 Next Generation". Genographic.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Indigenas del territorio Argentino: oralidad y supervivencia". Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ a b Revisionistas. La Otra Historia de los Argentinos Source: Argentina: de la Conquista a la Independencia. by C. S. Assadourian – C. Beato – J. C. Chiaramonte. Ed. Hyspamérica, Buenos Aires. (1986)

- ^ "Acerca de la Argentina: Primeros Conquistadores" [About Argentina: First Conquerors]. Government of Argentina (in Spanish). 2005. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010.

- ^ a b "La Inmigración en la República Argentina" [Immigration in the Argentine Republic] (in Spanish). oni.escuelas.edu.ar. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- ^ Argentina 200 Años. Vol. 9 1820–1830. Editor José Alemán. Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino. Buenos Aires. 2010.

- ^ Buenos Aires Census 1855 (Spanish). UAEM, October 2006.

- ^ Levene, Ricardo. History of Argentina. University of North Carolina Press, 1937.

- ^ Federaciones Regionales Archived 2 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine www.feditalia.org.ar

- ^ a b "Yale immigration study". Yale.edu. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin (18 April 2011). The History of White People. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393079494.

- ^ "CELS Informe: Inmigrantes" [CELS Report: Immigrants] (PDF). cels.org.ar (in Spanish). 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Argentina: 1516–1982. From Spanish Colonisation to the Falklands War by David Rock. University of California Press, 1987. p.166.

- ^ "Inmigrantes en Argentina. Censo Argentino de 1914". Redargentina.com. 22 February 1999. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Dirección Nacional de Migraciones: Inmigración 1857–1920" (PDF). Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Claude Wey (2002). "L'Émigration Luxembourgeoise vers l'Argentine" [Emigration from Luxembourg to Argentina] (PDF). Migrance (in French) (20). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ Dirección Nacional de Inmigraciones: Hotel de Inmigrantes. See pie chart at the bottom on the left; Inmigrantes Arribados: 5.235.394

- ^ Includes Ukrainian, Jewish and Belarus in eastern Poland. Los colonos eslavos del Nordeste Argentino Archived 24 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ It includes Ukrainian, Volga Germans, Belarusian, Polish, Lithuanian etc. which then be submitted to the Russian Zarato admitted with Russian passports.

- ^ The distinction between Turkish, Palestinian, Syria, Lebanese and Arabs only made at the official level after 1920. until that time, all they emigrated with Turkish passport-which generalized the use of the term until today-to be legally residing in the Ottoman Empire. In fact, each identified with their village or town of origin.

- ^ In 1867 the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary signed a treaty known as the Ausgleich, creating a dual monarchy Austria-Hungary. It disintegrated in late 1918 to the World War I. What was the Austro-Hungarian Empire is currently distributed in thirteen European states that are now the nations of Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and regions Vojvodina to Serbia, Bocas de Kotor to Montenegro, Trentino South Tyrol and Trieste in Italy, Transylvania and of the Banat to Romania, Galicia to Poland and Ruthenia (region Subcarpathian to Ukraine), most of the immigrants to "Austro-Hungarian" passport were people from groups: Croatian, Polish, Hungary, Slovenian, Czech, Romanian and even Italian Northeast.

- ^ The United Kingdom to 1922 included all Ireland; much of the British immigrants – then commonly called "English" – were of Irish origin, coupled with the Welsh and Scottish source population.

- ^ Thomas, Adam, ed. (2005). Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics and History. Transatlantic Relations: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-85109-628-2. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Portugal to 1974 owned units as Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, Macao, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, Timor Leste

- ^ The state known generically as Yugoslavia grouped, between 1918 and 1992, existing independent states of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

- ^ "¿Quién es el político que viajó a Italia para conocer sus orígenes?" [Who is the politician who travelled to Italy to learn about their origins?] (in Spanish). Minutouno.com. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Migration and Nationality Patterns in Argentina. Source: Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, 1976.

- ^ Piero on line (biografía). (Spanish)

- ^ Rodolfo Ranni: "Me hice actor para ganar guita." Diario Clarín (Spanish)

- ^ Se suicidó Gianni Lunadei. Edant.clarin.com. (Spanish)

- ^ Murió César Civita, el gran creador de la editorial Abril. Diario La Nación. (Spanish)

- ^ Francisco Macri. Fundación Kónex. (Spanish)

- ^ Friendlysoft Desarrollo web. "Corazón de chacarero.Fruticultura Sur. (Spanish)". Fruticulturasur.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Página/12 : radar". Pagina12.com.ar. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Goni, Uki (23 February 2009). "Argentina Deports a Holocaust-Denying Bishop". Time. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Dagmar Hagelin". Desaparecidos. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Oriana Fallaci, Cambio 16, June 1982, Available Online [1][permanent dead link] "Si, señora periodista, desciendo de italianos. Mis abuelos eran italianos. Mi abuelo de Génova y mi abuela de Calabria. Vinieron aquí con las oleadas de inmigrantes que se produjeron al comienzo de siglo. Eran obreros pobres, pronto hicieron fortuna." ("Yes, madam reporter, I'm descended from Italians. My grandparents were Italian. My grandfather came from Genoa and my grandmother from Calabria. They came here with the waves of immigrants that occurred at the beginning of the century. They were poor workers, they soon made a fortune.")

- ^ The Nunca Más (Never Again) CONADEP Report.

- ^ "Inmigración, Cambio Demográfico y Desarrollo Industrial en la Argentina". Alfredo Lattes and Ruth Sautu. Cuaderno Nº 5 del CENEP (1978). Cited in Argentina: 1516–1982 From Spanish Colonisation to the Falklands War by David Rock. University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 0-520-05189-0

- ^ «A witness narrates how a Bolivian woman was thrown off a train: Tale of a Journey to Xenophobia (Spanish)» by Cristian Alarcón. Diario Página/12, 2 June 2001.

- ^ «A bullet loaded with racist hatred (Spanish)», Diario Página/12, 9 April 2008.

- ^ Rocio Scheytt (28 March 2010). "Trata de personas en Argentina" (in Spanish). perfilcristiano.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012.

- ^ Forced Labor in Argentina (Spanish) Diario Clarín, 5 July 2000.

- ^ a b c Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of Three Cultural Areas of the Americas at Beginning of the XXI Century] (PDF). Convergencia (in Spanish). 38 (May–August): 185–232. ISSN 1405-1435. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2008: see table on page 218

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Medina Lois, Ernesto, y Ana María Kaempffer R. (1979). "Capítulo Segundo: La situación de salud chilena y sus factores condicionantes - Población y características demográficas: Estructura racial". Biblioteca digital de la Universidad de Chile. Elementos de salud pública.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tabela 1.3.1 - População residente, por cor ou raça, segundo o sexo e os Sexo e grupos de idade População residente" (PDF). Ibge.gov.br. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Brancos são menos da metade da população pela primeira vez no Brasil". Cotidiano.

- ^ "Resultado Básico del XIV Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2011 (Mayo 2014)" (PDF). Ine.gov.ve. p. 29.

- ^ "Colombia: A Country Study" (PDF). Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress of the United States of America. 2010. pp. 86–87.

- ^ Pastore, Carlos (1972). La lucha por la tierra en el Paraguay: Proceso histórico y legislativo. Antequera. p. 526.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "National Household Survey, 2006: Ancestry (Spanish)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ La Nación: Napolitanos y porteños, unidos por el acento (in Spanish)

- ^ National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC), 2001.

- ^ "Colectividad Uruguaya - Las distintas corrientes y sus correspondientes fechas" [Uruguayan community - The different streams and their corresponding dates] (in Spanish). Oni.escuelas.edu.ar. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Recent Migration from Central and Eastern Europe to Argentina, a Special Treatment? (Spanish) by María José Marcogliese. Revista Argentina de Sociología, 2003.

- ^ Ukrainians, Russians and Armenians, from professionals to security guardians. (Spanish) Archived 15 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Florencia Tateossian. Le Monde Diplomatique, June 2001.

- ^ Some Romanians make miracles to survive in Buenos Aires. (Spanish) by Evangelina Himitian. La Nación, 20 February 2000.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau; Data Set: 2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates; Survey: American Community Survey. Retrieved 7 November 2009

- ^ Ben Cahoon. "Uruguay". World Statesmen.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Argentina: Land of the Vanishing Blacks. by Era Bell Thompson. Ebony Magazine. October 1973.

- ^ "Countries and their Culture: Argentina". Everyculture.com. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Verónica Dema (20 September 2012). "Fin del misterio: muestran la partida de nacimiento de Gardel" [End of the mystery: they show Gardel's birth certificate]. La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Collier, Simon (1986). The Life, Music, and Times of Carlos Gardel. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-8229-8498-9.

- ^ Barsky, Julián; Barsky, Osvaldo (2004). Gardel: La biografía (in Spanish). Taurus. ISBN 987-04-0013-2.

- ^ Ruffinelli, Jorge (2004). La sonrisa de Gardel: Biografía, mito y ficción (in Spanish). Ediciones Trilce. p. 31. ISBN 9974-32-356-8.

- ^ Ástor Piazzolla Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Associazione musicale culturale Domenico Sarro (Italian)

- ^ "Evolution of Tango (Spanish)". Tangoporsisolo.com.br. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Beginnings of Tango (Spanish). by Jorge Gutman. De Norte a Sur (Noticiero Online). Año 21, Nº 241. September 2001.

- ^ Rodríguez Villar, Antonio. "Tango and our native music". todotango.com. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ "Chango Spasiuk" (in Spanish). Estación Tierra.

- ^ "Argentina Portal. Culture. Dances. (Spanish)". Argentina.gov.ar. Archived from the original on 14 August 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Daus, Roberto (May 1999). "Juan Manuel Fangio - El más grande de todos los tiempos" [Juan Manuel Fangio - The greatest of all time] (in Spanish). fcaglp.unlp.edu.ar. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ Argentina 200 Años. Vol. 6 1860–1869. Editor José Alemán. Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino. Buenos Aires. 2010.

- ^ History of a Mighty House (Spanish) Archived 13 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Diario Clarín, Buenos Aires, 21 February 2003.

- ^ a b Argentina 200 Años. Vol. 9 1890–1899. Editor José Alemán. Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino. Buenos Aires. 2010.

- ^ "Fútbol". www.goal.com. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Los Deportes y su Historia" [The History of Sports]. Government of Argentina (in Spanish). 2005. Archived from the original on 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Mi Parentela: Repartición del apellido Vilas" [My Kinfolk: Distribution of the surname Vilas]. miparentela.com (in Spanish). 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ^ "F1 Fanatics: Juan Manuel Fangio". F1fanatics.wordpress.com. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b Occhiuzzi, Javier M. (13 December 2014). "Historia del Boxeo - Nicolino Locche: vida y obra del intocable" [History of Boxing - Nicolino Locche: Life and Work of the Untouchable] (in Spanish). Laizquierdadiario.com. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ Larra, Raúl (1975). Jorge Newbery, Buenos Aires: Schapire, page 48.

- ^ Magazine "Historia de Junín", by Roberto Dimarco. Year 1, Nº 6, May 1969. According to this source, Luis Firpo's father, Agustín Firpo, arrived in Junín in 1887 from Italy, and married a Spaniard woman, Ángela Larroza in 1888. The couple had four children, Luis Firpo being the second child.

- ^ Locche. El último amague. Diario Clarín, 8 September 2005.

- ^ "Welsocme Argentina: Golf". Welcomeargentina.com. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ (in Spanish) History of the Argentine Hockey Confederation, Web.archive.org

- ^ Falleció Clodomiro Cortoni La Nación (in Spanish)