Euphemism

This article possibly contains original research. (August 2021) |

A euphemism (/ˈjuːfəmɪzəm/ YOO-fə-miz-əm) is an innocuous word or expression used in place of one that is deemed offensive or suggests something unpleasant.[1] Some euphemisms are intended to amuse, while others use bland, inoffensive terms for concepts that the user wishes to downplay. Euphemisms may be used to mask profanity or refer to topics some consider taboo such as mental or physical disability, sexual intercourse, bodily excretions, pain, violence, illness, or death in a polite way.[2]

Etymology

[edit]Euphemism comes from the Greek word euphemia (εὐφημία) which refers to the use of 'words of good omen'; it is a compound of eû (εὖ), meaning 'good, well', and phḗmē (φήμη), meaning 'prophetic speech; rumour, talk'.[3] Eupheme is a reference to the female Greek spirit of words of praise and positivity, etc. The term euphemism itself was used as a euphemism by the ancient Greeks; with the meaning "to keep a holy silence" (speaking well by not speaking at all).[4]

Purpose

[edit]Avoidance

[edit]Reasons for using euphemisms vary by context and intent. Commonly, euphemisms are used to avoid directly addressing subjects that might be deemed negative or embarrassing, such as death, sex, and excretory bodily functions. They may be created for innocent, well-intentioned purposes or nefariously and cynically, intentionally to deceive, confuse or deny. Euphemisms which emerge as dominant social euphemisms are often created to serve progressive causes.[5][6] The Oxford University Press's Dictionary of Euphemisms identifies "late" as an occasionally ambiguous term, whose nature as a euphemism for dead and an adjective meaning overdue, can cause confusion in listeners.[7]

Mitigation

[edit]Euphemisms are also used to mitigate, soften or downplay the gravity of large-scale injustices, war crimes, or other events that warrant a pattern of avoidance in official statements or documents. For instance, one reason for the comparative scarcity of written evidence documenting the exterminations at Auschwitz, relative to their sheer number, is "directives for the extermination process obscured in bureaucratic euphemisms".[8] Another example of this is during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, where Russian President Vladimir Putin, in his speech starting the invasion, called the invasion a "special military operation".[9]

Euphemisms are sometimes used to lessen the opposition to a political move. For example, according to linguist Ghil'ad Zuckermann, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu used the neutral Hebrew lexical item פעימות peimót (literally 'beatings (of the heart)'), rather than נסיגה nesigá ('withdrawal'), to refer to the stages in the Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank , in order to lessen the opposition of right-wing Israelis to such a move.[10] Peimót was thus used as a euphemism for 'withdrawal'.[10]: 181

Rhetoric

[edit]Euphemism may be used as a rhetorical strategy, in which case its goal is to change the valence of a description.[clarification needed]

Controversial use

[edit]Using a euphemism can in itself be controversial, as in the following examples:

- Reproductive health is used as a euphemism for the medical procedure of abortion, often employed for political reasons.[11] Many pro-choice institutions now advocate using the term "abortion" instead of relying on euphemisms in order to earn greater social acceptance of the procedure.[12]

- Affirmative action, meaning a preference for minorities or the historically disadvantaged, usually in employment or academic admissions. This term is sometimes said to be a euphemism for reverse discrimination, or, in the UK, positive discrimination, which suggests an intentional bias that might be legally prohibited, or otherwise unpalatable.[13]

- Enhanced interrogation is a euphemism for torture. For example, columnist David Brooks called the use of this term for practices at Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere an effort to "dull the moral sensibility".[14]

Online

[edit]The use of euphemism online is known as "algospeak" when used to evade automated online moderation techniques used on Meta and TikTok's platforms.[15][16][17][18][19] Algospeak has been used in debate about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[20][21]

Formation methods

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

Pronunciation (phonetic modification)

[edit]Phonetic euphemism is used to replace profanities and blasphemies, diminishing their intensity. To alter the pronunciation or spelling of a taboo word (such as a swear word) to form a euphemism is known as taboo deformation, or a minced oath. Such modifications include:

- Shortening or "clipping" the term, such as Jeez ('Jesus') and what the— ('what the hell').

- Mispronunciations, such as oh my gosh ('oh my God'), frickin ('fucking'), darn ('damn') or oh shoot ('oh shit'). This is also referred to as a minced oath. Feck is a minced oath for 'fuck', originating in Hiberno-English and popularised outside of Ireland by the British sitcom Father Ted.

- Using acronyms as replacements, such as SOB ('son of a bitch'). Sometimes, the word word or bomb is added after it, such as F-word ('fuck'), etc. Also, the letter can be phonetically respelled.

Understatement

[edit]Euphemisms formed from understatements include asleep for dead and drinking for consuming alcohol. "Tired and emotional" is a notorious British euphemism for "drunk", one of many recurring jokes popularized by the satirical magazine Private Eye; it has been used by MPs to avoid unparliamentary language.

Substitution

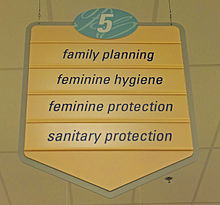

[edit]Pleasant, positive, worthy, neutral, or nondescript terms are often substituted for explicit or unpleasant ones, with many substituted terms deliberately coined by sociopolitical movements, marketing, public relations, or advertising initiatives, including:

- meat packing company for 'slaughterhouse' (avoids entirely the subject of killing); natural issue or love child for 'bastard'; let go for 'fired/sacked', etc.

Some examples of Cockney rhyming slang may serve the same purpose: to call a person a berk sounds less offensive than to call a person a cunt, though berk is short for Berkeley Hunt,[22] which rhymes with cunt.[23]

Metaphor

[edit]- Metaphors (beat the meat, choke the chicken, or jerkin' the gherkin for 'masturbation'; take a dump and take a leak for 'defecation' and 'urination', respectively)

- Comparisons (buns for 'buttocks', weed for 'cannabis')

- Metonymy (men's room for 'men's restroom/toilet')

Slang

[edit]The use of a term with a softer connotation, though it shares the same meaning. For instance, screwed up is a euphemism for 'fucked up'; hook-up and laid are euphemisms for 'sexual intercourse'.

Foreign words

[edit]Expressions or words from a foreign language may be imported for use as euphemism. For example, the French word enceinte was sometimes used instead of the English word pregnant;[24] abattoir for slaughterhouse, although in French the word retains its explicit violent meaning 'a place for beating down', conveniently lost on non-French speakers. Entrepreneur for businessman, adds glamour; douche (French for 'shower') for vaginal irrigation device; bidet ('little pony') for vessel for anal washing. Ironically, although in English physical "handicaps" are almost always described with euphemism, in French the English word handicap is used as a euphemism for their problematic words infirmité or invalidité.[25]

Periphrasis/circumlocution

[edit]Periphrasis, or circumlocution, is one of the most common: to "speak around" a given word, implying it without saying it. Over time, circumlocutions become recognized as established euphemisms for particular words or ideas.

Doublespeak

[edit]Bureaucracies frequently spawn euphemisms intentionally, as doublespeak expressions. For example, in the past, the US military used the term "sunshine units" for contamination by radioactive isotopes.[26] The United States Central Intelligence Agency refers to systematic torture as "enhanced interrogation techniques".[27] An effective death sentence in the Soviet Union during the Great Purge often used the clause "imprisonment without right to correspondence": the person sentenced would be shot soon after conviction.[28] As early as 1939, Nazi official Reinhard Heydrich used the term Sonderbehandlung ("special treatment") to mean summary execution of persons viewed as "disciplinary problems" by the Nazis even before commencing the systematic extermination of the Jews. Heinrich Himmler, aware that the word had come to be known to mean murder, replaced that euphemism with one in which Jews would be "guided" (to their deaths) through the slave-labor and extermination camps[29] after having been "evacuated" to their doom. Such was part of the formulation of Endlösung der Judenfrage (the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question"), which became known to the outside world during the Nuremberg Trials.[30]

Lifespan

[edit]

Frequently, over time, euphemisms themselves become taboo words, through the linguistic process of semantic change known as pejoration, which University of Oregon linguist Sharon Henderson Taylor dubbed the "euphemism cycle" in 1974,[31] also frequently referred to as the "euphemism treadmill", as coined by Steven Pinker.[32] For instance, the place of human defecation is a needy candidate for a euphemism in all eras. Toilet is an 18th-century euphemism, replacing the older euphemism house-of-office, which in turn replaced the even older euphemisms privy-house and bog-house.[33] In the 20th century, where the old euphemisms lavatory (a place where one washes) and toilet (a place where one dresses[34]) had grown from widespread usage (e.g., in the United States) to being synonymous with the crude act they sought to deflect, they were sometimes replaced with bathroom (a place where one bathes), washroom (a place where one washes), or restroom (a place where one rests) or even by the extreme form powder room (a place where one applies facial cosmetics).[citation needed] The form water closet, often shortened to W.C., is a less deflective form.[citation needed] The word shit appears to have originally been a euphemism for defecation in Pre-Germanic, as the Proto-Indo-European root *sḱeyd-, from which it was derived, meant 'to cut off'.[35]

Another example in American English is the replacement of "colored people" with "Negro" (euphemism by foreign language), which itself came to be replaced by either "African American" or "Black".[36] Also in the United States the term "ethnic minorities" in the 2010s has been replaced by "people of color".[36]

Venereal disease, which associated shameful bacterial infection with a seemingly worthy ailment emanating from Venus, the goddess of love, soon lost its deflective force in the post-classical education era, as "VD", which was replaced by the three-letter initialism "STD" (sexually transmitted disease); later, "STD" was replaced by "STI" (sexually transmitted infection).[37]

Intellectually-disabled people were originally defined with words such as "morons" or "imbeciles", which then became commonly used insults. The medical diagnosis was changed to "mentally retarded", which morphed into the pejorative, "retard", against those with intellectual disabilities. To avoid the negative connotations of their diagnoses, students who need accommodations because of such conditions are often labeled as "special needs" instead, although the words "special" or "sped" (short for "special education") have long been schoolyard insults.[38][better source needed] As of August 2013, the Social Security Administration replaced the term "mental retardation" with "intellectual disability".[39] Since 2012, that change in terminology has been adopted by the National Institutes of Health and the medical industry at large.[40] There are numerous disability-related euphemisms that have negative connotations.

See also

[edit]- Call a spade a spade

- Code word (figure of speech)

- Dead Parrot sketch

- Distinction without a difference

- Dog whistle (politics)

- Double entendre

- Dysphemism

- Emotive conjugation

- Expurgation (often called bowdlerization, after Thomas Bowdler)

- Framing (social sciences)

- Minimisation

- Persuasive definition

- Polite fiction

- Political correctness

- Political euphemism

- Puns

- Sexual slang

- Spin (propaganda)

- Statistext

- Word play

- Word taboo

References

[edit]- ^ "Euphemism". Webster's Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "euphemism (n.)". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, φήμη". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ "'Euphemism' Etymology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ "How strategic lingo swallowed progressive thought". Washington Examiner. 19 May 2023.

- ^ "THE MORAL CASE AGAINST EQUITY LANGUAGE". The Atlantic. 2 March 2023.

- ^ Holder, R. W. (2008). Dictionary of Euphemisms. Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-19-9235179.

- ^ Ryback, Timothy (15 November 1993). "Evidence of Evil". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Year in a word: 'Special operation'". Financial Times. 29 December 2022.

- ^ a b Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. p. 181.

- ^ Lowry, Rich (2 May 2013). "The euphemism imperative". Politico. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Just say abortion". Planned Parenthood Advocacy Fund of Massachusetts. 14 June 2021. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024.

- ^ Affirmative action as euphemism:

- "Style Guide". The Economist. 10 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

Uglier even than human-rights abuses and more obscure even than comfort station, affirmative action is a euphemism with little to be said for it.

- Custred, Glynn & Campbell, Tom (2 May 2001). "Affirmative Action: A Euphemism for Racial Profiling by Government". Investors Business Daily. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Bayan, Rick (December 2009). "Affirmative Action". The New Moderate. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Will, George F. (25 April 2014). "The Supreme Court tangles over euphemisms for affirmative action". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- Raza, M. Ali; Janell Anderson, A.; Custred, Harry Glynn (1999). "Chapter 4: Affirmative Action Diversity: A Euphemism for Preferences, Quotas, and Set-asides". The Ups and Downs of Affirmative Action Preferences. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 75. ISBN 9780275967130. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- A Journalist's Guide to Live Direct and Unbiased News Translation. Writescope Publishers. 2010. p. 195. ISBN 9780957751187. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

In modern times, various social and political movements have introduced euphemisms, from affirmative action to political correctness to international conflicts, which are linguistically and culturally driven.

- "Style Guide". The Economist. 10 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ Enhanced interrogation as euphemism:

- Brooks, David; Shields, Mark; Woodruff, Judy (12 December 2014). "Shields and Brooks on the CIA interrogation report, spending bill sticking point". PBS Newshour. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

[T]he report ... cuts through the ocean of euphemism, the EITs, enhanced interrogation techniques, and all that. It gets to straight language. Torture – it's obviously torture. ... the metaphor and the euphemism is designed to dull the moral sensibility.

- Williams, Brian; Panetta, Leon (3 May 2011). "Transcript of interview with CIA director Panetta". NBC News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

Enhanced interrogation has always been a kind of handy euphemism (for torture)

- Pickering, Thomas (16 April 2013). "America must atone for the torture it inflicted". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

Let's stop resorting to euphemisms and call "enhanced interrogation techniques" — including but not limited to waterboarding — what they actually are: torture.

- Brooks, David; Shields, Mark; Woodruff, Judy (12 December 2014). "Shields and Brooks on the CIA interrogation report, spending bill sticking point". PBS Newshour. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Lorenz, Taylor (8 April 2022). "Internet 'algospeak' is changing our language in real time, from 'nip nops' to 'le dollar bean'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Kreuz, Roger J. (13 April 2023). "What is 'algospeak'? Inside the newest version of linguistic subterfuge". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024.

- ^ Tellez, Anthony (31 January 2023). "'Mascara,' 'Unalive,' 'Corn': What Common Social Media Algospeak Words Actually Mean". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023.

- ^ Levine, Alexandra S. (19 September 2022). "From Camping to Cheese Pizza, 'Algospeak' is Taking over Social Media". Forbes. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023.

- ^ Klug, Daniel; Steen, Ella; Yurechko, Kathryn (2023). "How Algorithm Awareness Impacts Algospeak Use on TikTok". Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023. pp. 234–237. doi:10.1145/3543873.3587355. ISBN 9781450394192. S2CID 258377709.

- ^ Nix, Naomi (20 October 2023). "Pro-Palestinian creators use secret spellings, code words to evade social media algorithms". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "How pro-Palestinians are using 'Algospeak' to dodge social media scrutiny and disseminate hateful rhetoric". Fox News. 23 October 2023.

- ^ although properly pronounced in upper-class British-English "barkley"

- ^ "definition of 'berk'/'burk'". Collins Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Definition of enceinte". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "HANDICAP in French - Cambridge Dictionary".

- ^ McCool, W.C. (6 February 1957). Return of Rongelapese to their Home Island – Note by the Secretary (PDF) (Report). United States Atomic Energy Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred W. (2006). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. New York: Metropolitan / Owl Book / Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 9780805082487 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Alexander (1974). The Gulag Archipelago. Vol. I. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 6. ISBN 006092103X.

- ^ "Holocaust-history.org". Holocaust-History.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "Wannsee Conference and the 'Final Solution'". Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Henderson Taylor, Sharon (1974). "Terms for Low Intelligence". American Speech. 49 (3/4): 197–207. doi:10.2307/3087798. JSTOR 3087798.

- ^ Pinker, Steven (5 April 1994). "Opinion | The Game of the Name". The New York Times.

- ^ Bell, Vicars Walker (1953). On Learning the English Tongue. Faber & Faber. p. 19.

The Honest Jakes or Privy has graduated via Offices to the final horror of Toilet.

- ^ French toile, fabric, a form of curtain behind which washing, dressing and hair-dressing were performed (Larousse, Dictionnaire de la langue française, "Lexis", Paris, 1979, p. 1891)

- ^ Ringe, Don (2006). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199552290.

- ^ a b Demby, Gene (7 November 2014). "Why We Have So Many Terms for 'People of Color'". NPR. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "STI vs. STD: Overcoming the Stigma". PowerToDecide.org. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Hodges, Rick (1 July 2020). "The Rise and Fall of 'Mentally Retarded'". Medium. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Change in Terminology: 'Mental Retardation' to 'Intellectual Disability'". Federal Register. 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ Nash, Chris; Hawkins, Ann; Kawchuk, Janet; Shea, Sarah E. (17 February 2012). "What's in a name? Attitudes surrounding the use of the term 'mental retardation'". Paediatrics & Child Health. 17 (2): 71–74. doi:10.1093/pch/17.2.71. ISSN 1205-7088. PMC 3299349. PMID 23372396.

Further reading

[edit]- Allan, Keith; Burridge, Kate (1991). Euphemism & Dysphemism: Language Used as Shield and Weapon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0735102880.

- Benveniste, Émile. "Euphémismes anciens and modernes". Problèmes de linguistique générale (in French). Vol. 1. pp. 308–314. Originally published in: Die Sprache. Vol. I. 1949. pp. 116–122.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Enright, D. J. (1986). Fair of Speech. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192830600.

- Fussell, Paul (1983). Class: A Guide Through the American Status System. Touchstone / Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671792253.

- Holder, R. W. (2003). How Not to Say What You Mean: A Dictionary of Euphemisms. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198607628.

- Keyes, Ralph (2010). Euphemania: Our Love Affair with Euphemisms. Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316056564.

- Maledicta: The International Journal of Verbal Aggression. ISSN: 0363-3659. LCCN: 77649633. OCLC: 3188018.

- McGlone, M. S.; Beck, G.; Pfiester, R. A. (2006). "Contamination and camouflage in euphemisms". Communication Monographs. 73 (3): 261–282. doi:10.1080/03637750600794296.

- Rawson, Hugh (1995). A Dictionary of Euphemism & Other Doublespeak (second ed.). Crown Publishers. ISBN 0517702010.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 678. ISBN 0674362500.

- Heidepeter, Philipp; Reutner, Ursula (2021). "When Humour Questions Taboo: A Typology of Twisted Euphemism Use". Pragmatics & Cognition. 28 (1): 138–166. doi:10.1075/pc.20027.hei. ISSN 0929-0907.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of euphemism at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of euphemism at Wiktionary