Aston

| Aston | |

|---|---|

| |

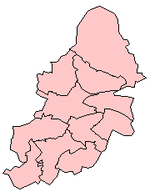

Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 22,636 (2011. Ward)[1] |

| • Density | 10,833 per square mile (4,183/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SP072889 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B6 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, in the county of the West Midlands, England. Located immediately to the north-west of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority. It is approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Birmingham City Centre.[2]

History

[edit]Aston was first mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086 as "Estone", having a mill, a priest and therefore probably a church, woodland and ploughland. The Church of Saints Peter and Paul was built in medieval times to replace an earlier church. The body of the church was rebuilt by J. A. Chatwin during the period 1879 to 1890; the 15th century tower and spire, which was partly rebuilt in 1776, being the only survivors of the medieval building.[3]

The ancient parish of Aston (known as Aston juxta Birmingham) was large. It was separated from the parish of Birmingham by AB Row, which currently exists in the Eastside of the city at just 50 yards in length. Aston, as Aston Manor, was governed by a Local Board from 1869 and was created as an Urban District Council in 1903 before being absorbed in the expansion of the County Borough of Birmingham in 1911,[4] and a further part, Saltley was added in 1911.

In 1911 the civil parish had a population of 219,082.[5] On 1 April 1912 the parish was abolished and merged with Birmingham.[6] Old buildings which became popular within Aston included the Aston Hippodrome and the Bartons Arms public house. Gospel Hall on Park Lane was opened in 1892 and demolished in the 1970s to be rebuilt at the top of Park Lane in 1979. The original hall had a seating capacity of 73. Another meeting place was the Ellen Knox Memorial Hall which was next door to the Midland Vinegar Brewery. The brewery was owned by the Midland Brewery Company was built around 1877.[7] It was located on Upper Thomas Street. The brewery was a three-storey brick building with rounded corners, semi-circular windows and a slated roof. Other industry that was located in Aston include the Premier Motor Works which produced cars during the early 20th century. The works were situated at the junction of Aston Road and Dartmouth Street. On Miller Street was a tramcar depot which had a storage capacity of 104 tramcars. It opened in 1904 latterly being operated by the City of Birmingham Tramways Company Ltd on behalf of the Urban District Council before formally passing to Birmingham Corporation Tramways on 1 January 1912.[8]

Aston underwent large scale redevelopment following the Second World War. South Aston was designated a renewal area involving comprehensive redevelopment of the traditional area known as "Aston New Town".[9] The area, was more commonly called simply "Newtown" and is a large estate consisting of sixteen tower blocks, five of which have since been demolished. The project was approved in 1968. Three 20-storey tower blocks on the complex contained 354 flats alone.[10]

Today, Aston gives its name to Aston Villa F.C. and Aston University (the campus of which is not in Aston but about 1.3 miles to the south in Birmingham city centre). Aston University is one of four universities in Birmingham. Aston Villa have played at Villa Park since 1897, and it has traditionally been one of the largest football grounds in England that has staged many notable matches at club and international level. The park has also hosted other sports and events including international level rugby league and rugby union. This is one of the main attractions in this town.

Much of Aston consists of terraced houses that were built around the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Some of these houses were demolished in the late 1960s to make way for the Aston Expressway, which links Birmingham city centre to the M6 motorway.[11] In the late 1950s, Aston was the location of the famous 'Venus Baby' case of Cynthia Appleton (87 Fentham Road).[12]

By the early 1980s, Aston was suffering from severe deprivation with many of the terraced houses being outdated for the requirements of the time. Many of them lacked bathrooms and indoor toilets, whilst the vast majority were suffering from decay as a result of a lack of maintenance. There was speculation that the homes would be demolished, but Birmingham City Council made money available to the homeowners for them to be brought up to modern standards.

From 2001 to 2011, Aston underwent a £54 million Birmingham regeneration project named "Aston Pride", as part of the New Deal for Communities scheme in 2001. Many improvements were made, including reducing burglary, robbery and vehicle crime; spending £4 million on a health centre; and helping more than 1300 people find work (more than the target of 400).[13][full citation needed]

Crime

[edit]Crime levels in Aston have remained stagnant in recent years. In December 2010, there were 369 reported crimes, the majority being for antisocial behaviour, while in December 2019, there were 328, mostly for violent offences. The crime rate in the ward is 10.35, which is higher than in other areas like Handsworth Wood (6.59) but lower than Nechells (16.6).[14]

The majority of the crime is of the nature of violence, antisocial behaviour, vehicle crime, and robbery.[citation needed]

On 2 January 2003, gunmen shot at three innocent teenage girls who were celebrating the New Year in the Birchfield area near Aston. Two of the girls were killed and another was seriously injured. More than 18 bullets were fired from at least two weapons.[15] Four men were later tried and found guilty of murder in March 2005. Marcus Ellis (the half-brother of one of the two dead girls), Nathan Martin and Michael Gregory were sentenced to life imprisonment with recommended minimum terms of 35 years on two charges of murder and three of attempted murder. A fourth man, Rodrigo Simms, received life with a recommended minimum of 27 years for the same crimes.[16] A fifth defendant, Jermaine Carty, had walked free from court after being cleared of possessing a firearm.[17] The four men convicted were members of a notorious local gang known as the Burger Bar Boys, who had been trying to exact revenge on members of their rival gang the Johnson Crew: a notorious local gang originating in the mid-1980s.[18]

Politics

[edit]The Aston ward is represented by two Liberal Democrat councillors: Mumtaz Hussain and Ayoub Khan.[19]

In 2004, the ward saw a voter fraud scandal in which Labour councillors were accused of a systematic attempt to rig elections. They had set up a "vote-rigging factory" in a disused warehouse, stealing and intercepting hundreds and possibly thousands of ballot papers to achieve this.[20] Three councillors, Mohammed Islam, Muhammad Afzal (later cleared of wrongdoing) and Mohammed Kazi were accused of voter fraud, with the elections having to be rerun. All three were barred from standing in the following election.[21][22]

Aston is part of the Birmingham Ladywood constituency, held by Labour since 1940 and represented by Labour MP Shabana Mahmood since 2010.

Demographics

[edit]

The 2011 census found that 22,636 people were living in Aston. It is the sixth most populous ward in the city.[23]

It is a very ethnically diverse community, with 44% of the population born outside the United Kingdom. The largest ethnic group was Asian at 69.1%. More specifically, the Pakistani ethnic group was the largest at 30.9% of all Asians. Black British was the second largest ethnic group at 16.4%. White British was the third largest ethnic group at 7.8%.[23]

The ethnic makeup of the area drastically changed in the 1950s and 1960s with immigration from the Commonwealth. Most of the immigrants were from the Indian subcontinent most notably from Pakistan, though a significant number were also from the Caribbean.[23][full citation needed]

Aston is a young ward, with 33.5% of the population under 18, compared to the Birmingham average of 25.5%.[23]

31.7% of residents in Aston have no qualifications, higher than the Birmingham average of 20.8%. Moreover, 15.6% do not speak English as their main language and cannot speak it well, well above the national average of 1.9%.[23][full citation needed]

Aston has one of the highest rates of unemployment in the city, with 57.8% of residents classed as economically active compared to the city average of 69.3% and national average of 77%. It is the 11th most deprived ward in the city.[23][full citation needed]

The majority of employed residents (56%) work in lower skilled occupations, such as caring, leisure and sales. The average income in Aston (£12,033) is 35% less than the average income (£18,788) in England as a whole.[23][full citation needed]

Education

[edit]

There are three secondary schools in Aston: Broadway Academy, refurbished and opened by the Duke of Kent in 2011,[24] King Edward VI Aston, the only grammar school in the constituency, and Aston Manor School.

There are seven primary schools: Aston Tower Community Primary School, Birchfield Community School, Manor Park Primary Academy, Mansfield Green E-ACT Academy, Sacred Heart Catholic Primary School, Prince Albert Primary School, and Yew Tree Community School.

Aston Library and Birchfield Library are within the ward. Birmingham City Council planned to permanently close Aston Library in 2017 to save money; however, the decision was reversed after public consultation, and it is now run by community organisations.[25]

Aston Cross

[edit]Aston Cross was once the home of Ansells Brewery and HP Sauce. The six-acre Aston site was purchased by developer Chancerygate in 2007 at £800,000 per acre, but they subsequently sold it for half that price and it now houses a distribution warehouse for East End Foods. Aston Manor Brewery (Now Aston Manor Cider) was started in Thimble Mill Lane in 1982 by former employees of Ansell's after Ansell's Aston Brewery closed.

From 1956 to 1969, Aston Cross was the Midlands base of Associated Television (ATV) which had its Alpha Studios on Aston Road North. The ATV office building later became the studios of radio stations BRMB and XTRA-AM. Although both stations moved to Birmingham's Broad Street in the early 1990s, the building is still called Radio House. Launching in February 1974, BRMB was the UK's fourth Independent Local Radio station and, while in Aston, was the most listened to radio station in the West Midlands.[citation needed]

Places of interest

[edit]- Aston Hall

- Aston Reservoir

- Aston University

- Aston Villa Football Club and Villa Park

- Church of SS Peter & Paul, Aston

- Spaghetti Junction

- King Edward VI Aston

- Former Norton motorcycle factory

Notable residents

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

- Pal Aron,[26] English actor, attended Prince Albert Primary School in Aston.

- All the original members of the heavy metal band Black Sabbath were born and raised in the Aston area: Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Bill Ward and Geezer Butler. All four members lived here during the early years of the band's trajectory.[27]

- The author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle worked in the area for a short period.[28][29][30]

- Former Leicester City F.C. and WBA winger Lloyd Dyer was born in Aston.[31]

- Ateeq Javid,[26] English cricketer, attended Prince Albert Primary School and Aston Manor School. Started career at Aston Manor CC.

- Victor Johnson, (1883–1951) was a track cycling racer who, in 1908, won a gold medal at the Olympics, became 'World Amateur Sprint Champion' and the 'British National Quarter-mile Champion'.

- Albert Ketèlbey, composer, conductor and pianist, was born in Aston on 9 August 1875.

- Harry Shelvoke, founding member of Shelvoke and Drewry, born in Aston in 1877.

- John Benjamin Stone, a politician and prolific photographer, was born in Aston and inherited his father's local glass manufacturing business.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Birmingham Ward population 2011". Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Overview | Aston local history | Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Early history | Aston local history | Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Overview | Aston local history | Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk.

- ^ "Population statistics Aston AP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ "Relationships and changes Aston AP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Douglas Hickman (1970). Birmingham. Studio Vista Limited. p. 40.

- ^ "Astonbrook through Astonmanor: Aston Development". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ "www.bgfl.org". www.bgfl.org.

- ^ "Newtown". Emporis. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Defining Moment: Spaghetti Junction opens, May 24 1972". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "The riddle of Brum's alien baby; 44 Years on: Where is 'Boy From Venus'?". Free Online Library. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ BusinessLive (25 March 2011). "Aston Pride named best inner city regeneration scheme in UK". birminghampost. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ UKcrimestats. "Crime in Aston". www.ukcrimestats.com. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ "Gunmen fired more than 30 shots". BBC News. 3 January 2003. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "Life sentences for New Year killers". The Independent. 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Four jailed for New Year killings". BBC News. 21 March 2005. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Background: How the Burger Bar Boys and the Johnson crew came to the fore". Birmingham Mail. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Councillors by Ward: Aston". www.birmingham.gov.uk. Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Judge lambasts postal ballot rules as Labour 6 convicted of poll fraud". www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Judge upholds vote-rigging claims". 4 April 2005 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ BusinessLive (3 May 2005). "Councillor cleared of vote fraud". birminghampost. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Council, Birmingham City. "Aston Profile | Birmingham City Council". www.birmingham.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Keogh, Kat (8 December 2011). "£21 million Perry Barr school campus enjoys official opening by Duke of Kent". birminghammail. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ "New plans to save two libraries". BBC News. 7 February 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Look at us now! - Prince Albert School". www.princealbert.bham.sch.uk. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ "The street where heavy metal began". BBC News. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Authi, Jasbir; Bentley, David (27 May 2015). "Sir Arthur Conan Doyle convention is coming to Birmingham". birminghammail. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "From the Archives: Was Sherlock Holmes a Villa fan?". www.avfc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Stuff, Good. "Arthur Conan Doyle blue plaque in Birmingham". www.blueplaqueplaces.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Wollaston, Steve (20 January 2015). "Birmingham City: All you need to know about Lloyd Dyer". BirminghamLive. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- The City of Birmingham Baths Department 1851 – 1951, J. Moth, 1951

- 2001 Population Census information: Ward profiles

External links

[edit] Media related to Aston, Birmingham at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aston, Birmingham at Wikimedia Commons- Birmingham City Council: Aston Ward

- Aston Library

- Aston History

- The History Of Aston by Aston People

- Profile: Aston Birmingham