Estonian government-in-exile

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2022) |

Estonian government-in-exile Eesti Vabariigi valitsus eksiilis | |

|---|---|

| 1944–1992 | |

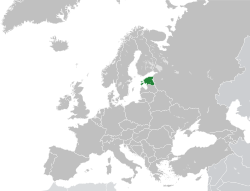

Location of Estonia | |

| Status | Government-in-exile |

| Capital | Tallinn |

| Capital-in-exile | |

| Prime Minister in duties of the President/Acting Prime Minister | |

• 1945–1963 | August Rei |

• 1990–1992 | Enno Penno |

| Historical era | Cold War |

• The National Committee of the Republic of Estonia proclaimed itself the supreme power of the Republic of Estonia | 1 August 1944 |

• Independence of Estonia recognized by the State Council of the Soviet Union | 6 September 1991 |

• Lennart Meri sworn in as the President of Estonia | 6 October 1992 |

| ISO 3166 code | EE |

The Estonian government-in-exile[1] was the formally declared governmental authority of the Republic of Estonia in exile, existing from 1944 until the reestablishment of Estonian sovereignty over Estonian territory in 1991. It traced its legitimacy through constitutional succession to the last Estonian government in power prior to the June 1940 Soviet invasion and occupation of the country. During its existence, it was the internationally recognized government of Estonia.

Background

[edit]The Soviet Armed Forces invaded and occupied Estonia on 16–17 June 1940. Soviet authorities arrested President Konstantin Päts and deported him to the USSR where he died in prison in 1956. Many members of the current and past governments were deported or executed, including eight former heads of state and 38 ministers. Those who survived went underground.

Sham elections were held on 14–15 July 1940 for a "People's Riigikogu," in which voters were presented with a single list dominated by communists. This election is now considered illegal and unconstitutional, since it was conducted on the basis of an electoral law that had not been approved by the upper chamber, as required by the Estonian constitution.[2] The upper house had been dissolved soon after the occupation and was never reconvened. The "People's Riigikogu" met on 21 July, with only one order of business–a resolution declaring Estonia a Soviet republic and petitioning to join the Soviet Union. The resolution passed unanimously.

Päts was forced to resign on either 21 July or 22 July, depending on the source. In accordance with Section 46 of the Estonian constitution, Johannes Vares, who had been serving as prime minister of a Communist-dominated puppet government appointed in June, then took over the president's powers under the title of "Prime Minister in duties of the President" and presided over the final stages of the Soviet takeover until Estonia was formally incorporated into the Soviet Union on 9 August.

However, Jüri Uluots, the last constitutional prime minister at the time of Soviet occupation, maintained that Vares' appointment as prime minister was illegitimate, and therefore he was the legitimate acting head of state with Päts' removal. Uluots attempted to appoint a new Estonian government in July 1941, at the beginning of the German occupation, but German authorities refused to recognize Estonia as a sovereign state.

History

[edit]National Committee under occupation by Nazi Germany

[edit]The National Committee of the Republic of Estonia was formed from individuals engaged in the Estonian government and anti-German resistance during the German occupation of Estonia. The Committee was led initially, from March 23, 1944, by Kaarel Liidak, then, from August 15 or 16, by Otto Tief. The Committee proclaimed itself the supreme power of the Republic of Estonia on August 1, 1944.

Failure to reestablish independence

[edit]

In June 1942 political leaders of Estonia who had survived Soviet repressions held a meeting hidden from the occupying powers in Estonia where the formation of an underground Estonian government and the options for preserving continuity of the republic were discussed.[3] On January 6, 1943, a meeting was held at the Estonian foreign delegation in Stockholm. In order to preserve the legal continuation of the Republic of Estonia, it was decided that Jüri Uluots had to continue to fulfill his responsibilities as prime minister, since he was the last legitimate incumbent in the post under the constitution.[3] On April 20, 1944, the Electoral Committee of the Republic of Estonia (Vabariigi Presidendi Asetäitja Valimiskogu, the institution specified in the Constitution for electing the Acting President of the Republic) held a clandestine meeting in Tallinn. The participants included:

- Jüri Uluots, the last Prime Minister of Estonia before the Soviet occupation.

- Johan Holberg, the substitute for Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.

- Otto Pukk, the Chairman of the Chamber of Deputies.

- Alfred Maurer, the Second deputy Vice-Chairman of the National Council.

- Mihkel Klaassen, Justice of the Supreme Court of Estonia.

The committee determined that Vares' appointment as prime minister by Päts had been illegal and that Uluots had ascended as prime minister in duties of the president from June 21, 1940, onwards.[4] On June 21, 1944, Uluots appointed Otto Tief as deputy prime minister. On September 18, 1944, Uluots, suffering from cancer, named Otto Tief the acting prime minister and appointed a government which consisted of 11 members. On September 20, 1944, Uluots, in failing health, departed for Sweden. Tief assumed office in accordance with the constitution and took the opportunity with the departure of the Germans to declare the legitimate Estonian government restored. Most of members of this government left from Tallinn on September 21 and Tief on September 22. As reported by the Royal Institute of International Affairs: on September 21 the Estonian national government was proclaimed, Estonian forces seized the government buildings in Toompea and ordered the German forces to leave.[5] The flag of Germany was replaced with the Estonian tricolour in the Pikk Hermann flag tower. Tief's government, however, failed to keep control, as Estonian military units led by Johan Pitka clashed with both Germans and Soviets. On September 22 the Soviets took control of Tallinn and took the Estonian flag down.

Flight ahead of Soviet forces

[edit]The Tief government fled Tallinn. The last meeting was held in Põgari village on September 22. However, the boat which was to rendezvous to evacuate them across the Baltic developed engine trouble and failed to arrive in time. Most of the members and officials, including Tief, were caught, jailed, deported, or executed by the advancing Soviets. Tief managed to survive a decade in Siberia and died back in Estonia in 1976. Only Kaarel Liidak, Minister of Agriculture, died in hiding on January 16, 1945.

Official declaration

[edit]After Uluots died on January 9, 1945, August Rei, as the most senior surviving member of the government, assumed the role of acting head of state. Rei was supported by the surviving members of the Tief government in Sweden. Rei was the last Estonian envoy in Moscow before the Soviet annexation and had managed to escape from Moscow through Riga to Stockholm in June 1940.[6]

Rei declared an official Estonian government in exile on January 12, 1953, in Oslo, Norway.[7] (Oslo, not Stockholm, was chosen because Norway did not have bans on such political activity, while Sweden had.)

However, another group of Estonian politicians believed a president should be elected through some representative body. This group was led by Alfred Maurer, who had been second deputy chairman of the National Council of Estonia prior to 1940. Maurer was elected Acting President of the Republic (Vabariigi Presidendi Asetäitja) in exile on March 3, 1953, in Augustdorf, Germany. While Maurer's lineage had more support among the exile community, he never appointed any new government (stating that Tief's government is still in office and there is no need for a new government) and this line became extinct upon Maurer's death a year-and-a-half later, on September 20, 1954. This left the Rei government as the sole contestant to legitimacy.

The position of acting head of government continued to be assumed by succession following Rei's death in 1963. From 1953 to 1992, five governments in exile were formed.

Diplomacy

[edit]Of the three Baltic states, only Estonia established a formal government-in-exile. In the cases of Latvia and Lithuania, sovereign authority had been vested in their diplomatic legations. Even with regard to Estonia, the legations were the primary instrument for the conduct of diplomacy and for administering the daily matters of state (such as issuing passports). Estonia's primary legation was the Consulate General in New York City.

Under the American Stimson Doctrine, the legitimacy of the Soviet occupation of Baltic states was never recognized. As primary diplomatic authority was exercised by the Estonian consulate in New York City,[8] the government-in-exile's role from Oslo was, to a great degree, symbolic in nature. The Estonian consulate in Ireland was in legal proceedings. Estonian ships were instructed to go to a Soviet port. Three Estonian ships (Otto, Piret, and Mall) and two from Latvia (Rāmava and Everoja) chose a neutral port in Ireland instead. Ivan Maisky, the Soviet Union's ambassador to the United Kingdom, applied to the High Court in Dublin for possession of the ships. Their owners could not be contacted. John McEvoy honorary consul of Estonia successfully opposed the action.[9] This was recalled by Toomas Hendrik Ilves, President of Estonia.[10]

However, the Estonian government-in-exile did serve to carry the continuity of the Estonian state forward. The last prime minister in the duties of the president, Heinrich Mark, ended the work of the government-in-exile when he handed over his credentials to incoming president Lennart Meri on October 8, 1992. Meri issued a statement thanking the Estonian government-in-exile for being the keepers of the legal continuity of the Estonian state.

List of acting prime ministers

[edit]This is the list of the acting prime ministers (peaministri asetäitjad) of the Estonian government-in-exile:

- Johannes Sikkar (12 January 1953 – 22 August 1960)

- Tõnis Kint (22 August 1960 – 1 January 1962)

- Aleksander Warma (1 January 1962 – 30 March 1963)

- Tõnis Kint (30 March 1963 – 23 December 1970)

- Heinrich Mark (8 May 1971 – 1 March 1990)

- Enno Penno (1 March 1990 – 15 September 1992)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Historical Dictionary of Estonia, 2004, p. 332 ISBN 0-8108-4904-6

- ^ Marek, Krystyna (1968). Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law. Librairie Droz. p. 386. ISBN 9782600040440.

- ^ a b Chronology Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine at the EIHC

- ^ L. Mälksoo, Professor Uluots, the Estonian Government in Exile and the Continuity of the Republic of Estonia in International Law, Nordic Journal of International Law, Volume 69, Number 3 / March, 2000

- ^ By Royal Institute of International Affairs. Information Dept. Published 1945

- ^ Diplomats Without a Country by James T. McHugh, James S. Pacy, 2001, p. 183 ISBN 0-313-31878-6

- ^ Plaque unveiled in Oslo to remember Estonia's exiled government

- ^ Kempster, Norman (31 October 1988). "Annexed Baltic States: Envoys Hold On to Lonely U.S. Postings". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Eire High Court: Zarine v. Owners, etc. S. S. Ramava, McEvoy & Ors. v. Owners, etc. S. S. Otto, McEvoy and Veldi v. Owners, etc. S. S. Piret and S. S. Mall, Eckert & Co. v. Owners, etc. S. S. Everoja". The American Journal of International Law. 36 (3 (july. 1942)). American Society of International Law: 490–504. July 1942. doi:10.2307/2192676. JSTOR 2192676. S2CID 246010571.

- ^ "President of the Republic at the State Dinner hosted by President T. E. Mary McAleese and Dr. Martin McAleese". President.ee. 14 April 2008. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

"... we are thankful that Ireland never recognised the illegal annexation of Estonia by the Soviet Union after the Second World War. We will never forget John McEvoy, Estonia's honorary consul in Dublin from 1938 to 1960. Among other things, one of his good deeds was helping to protect the interests of the Estonian shipowners ..."

References

[edit]- Mälksoo, Lauri (2000). Professor Uluots, the Estonian Government in Exile and the Continuity of the Republic of Estonia in International Law. Nordic Journal of International Law 69.3, 289-316.

- Made, Vahur. Estonian Government-in-Exile: a controversial project of state continuation. Estonian School of Diplomacy