Essay on the Life of Seneca

Essay on the Life of Seneca (French: Essai sur Sénèque) was one of the final works of Denis Diderot. It contains an analysis of the life and works of Seneca, criticism of La Mettrie and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, autobiographical notes, and a tribute to modern America. It was published in 1779. In 1782 a revised and expanded version of this essay titled Essay on the Reigns of Claudius and Nero (French: Essai sur les règnes de Claude et de Néron) was published.[1][2][3]

Background

[edit]After completing six volumes of a translation of Seneca's writings, La Grange had died in 1775. The final seventh volume was completed mainly by Naigeon. Diderot was requested by Naigeon and Baron d'Holbach to contribute a supplementary essay to this final volume. The writeup of Diderot began as an essay of a few pages but eventually grew to become a book size work.[4][5]

Content

[edit]On Seneca

[edit]For the first part of the essay, comprising Diderot's analysis of Seneca and his works, Diderot cites all the works of Seneca in his essay except the plays which, in Diderot's time, were thought to have been written by someone else. He cites several ancient and modern historians in this part of the essay.[4][5] He also gives biographical details about Seneca, and includes a defense of Seneca's conduct and behavior.[6] It has been suggested that the descriptions of Claudius and Nero in the expanded version of Diderot's essay are disguised portrayals of Louis XV and Louis XVI.[7][8] An alternative suggestion is that Diderot's Claudius and Nero are representative of Frederick the Great and Catherine the Great.[8][9]

Criticism of La Mettrie

[edit]Diderot's essay contains an attack on La Mettrie whose view of philosophical materialism was also the view of Diderot. The reason for Diderot's disapproval was that on the question of ethics, La Mettrie believed in hedonism; and Diderot feared that all those who believed in philosophical materialism would be painted as hedonists by their philosophical opponents. Diderot weaves the criticism of La Mettrie into his essay by mentioning that in ancient Rome there existed perverse men who were sought to be associated with philosophers by the enemies of the philosophers; the objective being to discredit the philosophers. Similarly, Diderot comments, the enemies of the philosophes have sought to discredit them by associating La Mettrie with them.[10][11][note 1]

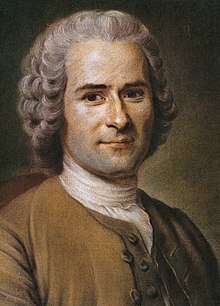

Criticism of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

[edit]Diderot's first essay includes criticism of Rousseau. Rousseau is not mentioned by name but is easily identifiable.[13][14] The criticism of Rousseau was presumably due to Diderot's fear about the revelations in Rousseau's Confessions. These were still unpublished, but Rousseau had begun public readings from his book prior to his death on July 2, 1778, and it was expected that they would now be published. It has been suggested that the criticism of Rousseau was aimed at protecting his reputation in the eyes of posterity.[15][16][17][18] In the first essay Diderot, while criticizing Suilius, an enemy of Seneca, writes: "One must, it seems to me, have some cruel repugnance against believing men of good will, to listen to the accusations of a Suilius, a professional informer, a corrupt fanatic and convicted criminal."[19] As a footnote to this comment, Diderot added a strong defense of Grimm, Mme. d'Épinay and himself from the charges made by Rousseau in the Confessions:

If, by a bizarrerie without exception, there should ever appear a work where honest people are pitilessly torn to pieces by a clever criminal [un artificieux scélérat]...look ahead and ask yourselves if an impudent fellow...who has confessed to a thousand misdeeds, can be...worthy of belief. What can calumny cost such a man?-what can one crime more or less add to the secret turpitude of a life hidden during more than fifty years behind the thickest mask of hypocrisy?...Detest the ingrate who speaks evil of his benefactors; detest the atrocious man who does not hesitate to blacken his old friends; detest the coward who leaves on his tomb the revelation of secrets confided to him...As for me, I swear that my eyes shall never be sullied by reading his work; I protest that I would prefer his invectives to his praise.[18][19]

The expanded essay of 1782 mentions Rousseau by name and includes further criticism of Rousseau.[15][20][21]

Tribute to America

[edit]Diderot's essay contains a passionate tribute to modern America; he hails the American Revolution which gave rise to a new nation in 1776, and its lessons for tyrants in Europe. He declares modern America to possibly be a novel feature in world affairs, and declares his hope that all Americans would continue to always enjoy freedom.[note 2] He expresses his hope that America would never engage in civil war, or come under despotic rule.[16][22]

Reception

[edit]Regarding historical part of the essay

[edit]Critical response to the first and historical part of the essay has generally been negative. Furbank, in his 1992 book, describes this part of the essay as mainly "empty rodomontade, a string of resounding sentiments aiming not at conviction but at applause. He fumes, he apostrophises, he utters ringing rebukes and challenges to imaginary enemies."[19] Fellows noted that no work of Diderot, with the possible exception of The Indiscreet Jewels, has received the kind of harsh criticism either in the eighteenth or the twentieth century as this essay of Diderot.[23][note 3]

Many contemporary critics had a similar opinion. A review in the Correspondance litteraire noted that Diderot's work was disjointed and discursive.[17] Another review in the Annee Litteraire first targeted Seneca by noting that there had never been a single instance of Seneca opposing Nero or confronting Nero with the crimes he had committed. The critic then went on to target Diderot:

M. Diderot knows no other style than that of the ode or epic. His weightiest dissertations are always animated by some Pindaric outbursts. The enthusiasm that possesses him, the demon who agitates him, never quit him; he is the Pythian priestess, forever seated on the tripod...Such is the motive and such are the means by which the prime architect of the Encyclopédie, past master of the art of inflating compilations, has been able to blow up to 520 pages an essay that would not contain a hundred if all that is irrelevant to the justification of Seneca were cut out.[25]

Regarding Rousseau

[edit]

Contemporary response to Diderot's criticism of Rousseau in the first essay was negative. Diderot was criticized for slandering a great man now unable to defend himself.[15] The Journal de littérature characterized Diderot's criticism of Rousseau as "a cowardly insult."[26] Meister commented that the criticism had angered Rousseau's supporters; whereas "the best friends of M. Diderot, who most have the right of sharing the just resentment that dictated the note, find it useless and out of place."[9]

Wilson, in his 1972 biography of Diderot, writes:

It was entirely gratuitous of Diderot to allude to Rousseau in the Essai sur Sénèque, and the fact that he did so proves what an obsession his frère ennemi had become. Probably it was Rousseau's impenetrability, his invulnerability, his inaccessibility that irritated Diderot through the years to the point of now impairing his judgement.[9]

By 1782, when Diderot's expanded essay featuring further criticism of Rousseau was published, public opinion had solidified in Rousseau's favor.[note 4] More and more people agreed with the view that Diderot was apprehensive of his portrayal in Rousseau's Confessions.[21]

Regarding America

[edit]Otis Fellows has characterized Diderot's tribute to America to be "natural and fitting": the new republic had taken birth recently and it was a beacon of hope and promise for people like Diderot. Also, Benjamin Franklin, with his arrival as the American ambassador in France, had won the approval of all the philosophes.[12]

Regarding La Mettrie

[edit]Otis Fellows characterizes Diderot's criticism of La Mettrie as being carried out more smoothly compared to the criticism of Rousseau.[15] Wilson writes that just as the hero of this work is Seneca, so its villain is La Mettrie.[27]

Notes

[edit]- ^ On the question of ethics, Diderot believed in the pursuit of happiness, combined with social and humanitarian obligations and concerns, and mastery over the self.[11][12]

- ^ Diderot writes in his essay:

Following centuries of constant oppression, may the revolution that has just come to pass beyond the seas, by offering all the inhabitants of Europe a refuge against fanaticism and tyranny, teach those who govern their fellowmen the legitimate use of their authority! May these worthy Americans, who have preferred to see their wives ill-used, their children killed, their houses destroyed, their fields laid waste, their cities burned, and themselves shed their blood and die, rather than lose the smallest part of their freedom, may they forestall the enormous increase and the unequal distribution of wealth, luxury, indolence, the corruption of morals, and see to the maintenance of their freedom and the preservation of their government.[22]

- ^ Fellows himself had a more positive opinion of this book; according to Fellows one can do worse than select this book if one is on a desert isle with a choice of any book of Diderot as reading material. "For as a few have noted, in this superb essay--with old age upon him--Diderot found in Roman history a pretext for an immense intellectual and moral last will and testament.[24]

- ^ On June 20, 1782, when the play Les Philosophes was performed at the Comédie-Française, reportedly under instruction from high authorities the curtain was lowered at the point where Rousseau was depicted eating a lettuce, so as to prevent a riot.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ Furbank (1992), pp. 406–10.

- ^ Wilson (1972), pp. 689–693.

- ^ Fellows (1977), pp. 161–168.

- ^ a b Wilson (1972), p. 690.

- ^ a b Fellows (1977), p. 163.

- ^ Furbank (1992), pp. 408–409.

- ^ Wilson (1972), p. 707.

- ^ a b Fellows (1977), p. 164.

- ^ a b c Wilson (1972), p. 692.

- ^ Fellows (1977), pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b Wilson (1972), pp. 708–709.

- ^ a b Fellows (1977), p. 166.

- ^ Fellows (1977), pp. 164–165.

- ^ Wilson (1972), pp. 691–693.

- ^ a b c d Fellows (1977), p. 165.

- ^ a b Furbank (1992), p. 408.

- ^ a b Wilson (1972), pp. 690–691.

- ^ a b Durant (1967), pp. 892–893.

- ^ a b c Furbank (1992), p. 407.

- ^ Furbank (1992), pp. 406–408.

- ^ a b c Wilson (1972), p. 705.

- ^ a b Fellows (1977), pp. 166–167.

- ^ Fellows (1977), p. 167.

- ^ Fellows (1977), p. 168.

- ^ Wilson (1972), p. 691.

- ^ Furbank (1992), p. 410.

- ^ Wilson (1972), p. 708.

Bibliography

[edit]- Wilson, Arthur M. (1972). Diderot. Oxford University Press.

- Fellows, Otis (1977). Diderot. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-6265-5.

- Furbank, P. N. (1992). Diderot: a critical biography. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780679414216.

- Durant, Will (1967). The Story of Civilization: Rousseau and Revolution. Simon and Schuster.