Enthesis

| Enthesis | |

|---|---|

Typical joint | |

| Identifiers | |

| TH | H3.03.00.0.00034 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

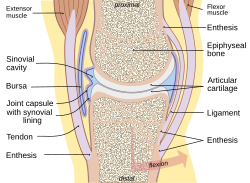

The enthesis (plural entheses) is the connective tissue which attaches tendons or ligaments to a bone.[1]

There are two types of entheses: fibrous entheses and fibrocartilaginous entheses.[2][3]

In a fibrous enthesis, the collagenous tendon or ligament directly attaches to the bone.

In a fibrocartilaginous enthesis, the interface presents a gradient that crosses four transition zones:[4]

- Tendinous area displaying longitudinally oriented fibroblasts and a parallel arrangement of collagen fibres

- Fibrocartilaginous region of variable thickness where the structure of the cells changes to chondrocytes

- Abrupt transition from cartilaginous to calcified fibrocartilage—often called 'tidemark' or 'blue line'

- Bone

Clinical significance

[edit]A disease of the entheses is known as an enthesopathy or enthesitis.[5]

Enthetic degeneration is characteristic of spondyloarthropathy and other pathologies.

The enthesis is the primary site of disease in ankylosing spondylitis.

Society and culture

[edit]Bioarchaeology

[edit]Entheses are widely recorded in the field of bioarchaeology where the presence of anomalies at these sites, called entheseal changes, has been used to infer repetitive loading to study the division of labour in past populations.[6] Several different recording methods have been proposed to record the variety of changes seen at these sites.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] However, research has shown that, whichever recording method is used, entheseal changes occur more frequently in older individuals.[16][8][17][18][19] Research demonstrates that diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis and calcific tendinitis,[20] also have to be taken into consideration. Experimental studies have demonstrated how loading history (physical activity) can increase the relative size of muscle attachment sites.[21][22][23][24]

History

[edit]"Enthesis" is rooted in the Ancient Greek word, "ἔνθεσις" or "énthesis," meaning “putting in," or "insertion." This refers to the role of the enthesis as the site of attachment of bones with tendons or ligaments. Relatedly, in muscle terminology, the insertion is the site of attachment at the end with predominant movement or action (opposite of the origin). Thus the words (enthesis and insertion [of muscle]) are proximal in the semantic field, but insertion in reference to muscle can refer to any relevant aspect of the site (i.e., the attachment per se, the bone, the tendon, or the entire area), whereas enthesis refers to the attachment per se and to ligamentous attachments as well as tendinous ones.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "enthesis". Medcyclopaedia. GE. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05.

- ^ Thomopoulos S, Birman V, Genin G, eds. (2012). Structural Interfaces and Attachments in Biology. New York: Springer. ISBN 9781461433163.

- ^ Rothrauff BB, Tuan RS (January 2014). "Cellular therapy in bone-tendon interface regeneration". Organogenesis. 10 (1): 13–28. doi:10.4161/org.27404. PMC 4049890. PMID 24326955.

- ^ Genin GM, Thomopoulos S (May 2017). "The tendon-to-bone attachment: Unification through disarray". Nature Materials. 16 (6): 607–608. Bibcode:2017NatMa..16..607G. doi:10.1038/nmat4906. PMC 5575797. PMID 28541313.

- ^ Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR, Bydder G, Best TM, Milz S (April 2006). "Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites ('entheses') in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load". Journal of Anatomy. 208 (4): 471–490. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00540.x. PMC 2100202. PMID 16637873.

- ^ Jurmain R, Cardoso FA, Henderson C, Villotte S (2011-01-01). Grauer AL (ed.). A Companion to Paleopathology. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 531–552. doi:10.1002/9781444345940.ch29. ISBN 9781444345940.

- ^ Hawkey DE, Merbs CF (1995-12-01). "Activity-induced musculoskeletal stress markers (MSM) and subsistence strategy changes among ancient Hudson Bay Eskimos". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 5 (4): 324–338. doi:10.1002/oa.1390050403. ISSN 1099-1212.

- ^ a b Henderson CY, Mariotti V, Pany-Kucera D, Villotte S, Wilczak C (2013-03-01). "Recording Specific Entheseal Changes of Fibrocartilaginous Entheses: Initial Tests Using the Coimbra Method". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 23 (2): 152–162. doi:10.1002/oa.2287. hdl:10316/44423. ISSN 1099-1212. S2CID 145571511.

- ^ Henderson CY, Mariotti V, Pany-Kucera D, Villotte S, Wilczak C (2016-09-01). "The New 'Coimbra Method': A Biologically Appropriate Method for Recording Specific Features of Fibrocartilaginous Entheseal Changes" (PDF). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 26 (5): 925–932. doi:10.1002/oa.2477. hdl:10316/44421. ISSN 1099-1212.

- ^ Mariotti V, Facchini F, Belcastro MG (June 2004). "Enthesopathies--proposal of a standardized scoring method and applications". Collegium Antropologicum. 28 (1): 145–159. PMID 15636072.

- ^ Mariotti V, Facchini F, Giovanna Belcastro M (March 2007). "The study of entheses: proposal of a standardised scoring method for twenty-three entheses of the postcranial skeleton". Collegium Antropologicum. 31 (1): 291–313. PMID 17598416.

- ^ Villotte S. "Practical protocol for scoring the appearance of some fibrocartilaginous entheses on the human skeleton".

- ^ Villotte S, Castex D, Couallier V, Dutour O, Knüsel CJ, Henry-Gambier D (June 2010). "Enthesopathies as occupational stress markers: evidence from the upper limb". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (2): 224–234. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21217. PMID 20034011.

- ^ Villotte S, Assis S, Cardoso FA, Henderson CY, Mariotti V, Milella M, et al. (June 2016). "In search of consensus: Terminology for entheseal changes (EC)" (PDF). International Journal of Paleopathology. 13: 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2016.01.003. hdl:10316/44443. PMID 29539508. S2CID 3902457.

- ^ Karakostis, Fotios Alexandros; Lorenzo, Carlos (2016). "Morphometric patterns among the 3D surface areas of human hand entheses". American Journal of Biological Anthropology. 160 (4): 694–707. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22999. PMID 27166777.

- ^ Cardoso FA, Henderson C (2013-03-01). "The Categorisation of Occupation in Identified Skeletal Collections: A Source of Bias?". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 23 (2): 186–196. doi:10.1002/oa.2285. hdl:10316/21142. ISSN 1099-1212.

- ^ Michopoulou E, Nikita E, Valakos ED (December 2015). "Evaluating the efficiency of different recording protocols for entheseal changes in regards to expressing activity patterns using archival data and cross-sectional geometric properties". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 158 (4): 557–568. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22822. PMID 26239396.

- ^ Milella M, Giovanna Belcastro M, Zollikofer CP, Mariotti V (July 2012). "The effect of age, sex, and physical activity on entheseal morphology in a contemporary Italian skeletal collection". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 148 (3): 379–388. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22060. PMID 22460619.

- ^ Henderson CY, Mariotti V, Santos F, Villotte S, Wilczak CA (2017-06-20). "The new Coimbra method for recording entheseal changes and the effect of age-at-death". BMSAP. 29 (3–4): 140–149. doi:10.1007/s13219-017-0185-x. hdl:10316/44430. ISSN 0037-8984. S2CID 29420179.

- ^ Henderson CY (March 2013). "Do diseases cause entheseal changes at fibrous entheses?". International Journal of Paleopathology. 3 (1): 64–69. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2013.03.007. hdl:10316/44415. PMID 29539362. S2CID 3916560.

- ^ Karakostis FA, Jeffery N, Harvati K (November 2019). "Experimental proof that multivariate patterns among muscle attachments (entheses) can reflect repetitive muscle use". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 16577. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916577K. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53021-8. PMC 6851080. PMID 31719626.

- ^ Karakostis FA, Wallace IJ, Konow N, Harvati K (December 2019). "Experimental evidence that physical activity affects the multivariate associations among muscle attachments (entheses)". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 222 (Pt 23): jeb213058. doi:10.1242/jeb.213058. PMC 6918778. PMID 31712353.

- ^ Castro AA, Karakostis FA, Copes LE, McClendon HE, Trivedi AP, Schwartz NE, Garland T (February 2022). "Effects of selective breeding for voluntary exercise, chronic exercise, and their interaction on muscle attachment site morphology in house mice". Journal of Anatomy. 240 (2): 279–295. doi:10.1111/joa.13547. PMC 8742976. PMID 34519035.

- ^ Karakostis, Fotios Alexandros; Wallace, Ian J. (2023-01-31). "Climbing influences entheseal morphology in the humerus of mice: An experimental application of the VERA methodology". American Journal of Biological Anthropology. 181: 130–139. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24700. ISSN 2692-7691. S2CID 256486347.

External links

[edit]- Enthesis information site at www.enthesis.info

- Image of enthesis at Medscape

- Enthesopathy and Soft Tissue Shadows at chiroweb.com

Further reading

[edit]- Resnick D, Niwayama G (January 1983). "Entheses and enthesopathy. Anatomical, pathological, and radiological correlation". Radiology. 146 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1148/radiology.146.1.6849029. PMID 6849029.